Abstract

Capsicum spp. are widely cultivated for use as vegetables and spices. The Kihara Institute for Biological Research, Yokohama City University, Japan, has stocks of approximately 800 lines of Capsicum spp. collected from various regions of Central and South America, the regions of origin for Capsicum spp. In this study, 5,751 primer pairs for simple sequence repeat markers, based on 118,060 publicly available sequences of expressed sequence tags of Capsicum annuum, were designed and subjected to a similarity search against the genomic sequence of tomato, a model Solanaceae species. Nucleotide sequences spanning 2,245 C. annuum markers were successfully mapped onto the tomato genome, and 96 of these, which spanned the entire tomato genome, were selected for further analysis. In genotyping analysis, 60 out of the 77 markers that produced specific DNA amplicons showed polymorphism among the Capsicum lines examined. On the basis of the resulting data, the 192 tested lines were grouped into five main clusters. The additional sequencing analysis of the plastid genes, matK and rbcL, divided the resources into three groups. As a result, 19 marker loci exhibited genotypes specific to species and cluster, suggesting that the DNA markers are useful for species identification. Information on the DNA markers will contribute to Capsicum genetics, genomics, and breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Capsicum is a member of the family Solanaceae. The Solanaceae includes the genus Solanum, to which tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and potato (S. tuberosum) also belong. The genus Capsicum includes several species of importance as food and spice crops. In addition, extracts are used as components of color dyes and medications. This genus includes several cultivated peppers, e.g., Capsicum annuum, including bell pepper, jalapeno, New Mexico chile, ancho, Anaheim chile, and banana pepper; Capsicum baccatum, including Ají amarillo; Capsicum chinense, including habanero; Capsicum frutescens, including Tabasco; and Capsicum pubescens, including rocoto peppers (Paran et al. 2007). All of these have interspecific compatibility with each other except for C. pubescens (Walsh and Hoot 2001). While the complete genome sequences of both tomato and potato have been released (The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium 2011; The Tomato Genome Consortium 2012), that of Capsicum has not been determined due to its large genome size (3.3 Gb, Moscone et al. 2003). However, other resources for genomic and genetic studies, viz., expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences, molecular markers, and genetic linkage maps, have been developed and used in quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping studies, genetic diversity analyses, and comparative genomics in the genus Capsicum (Jung et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2004; Minamiyama et al. 2006; Paran et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2009; Yi et al. 2006; Miura et al. 2012). Such efforts have revealed that the pepper genome has significant synteny with the tomato genome (Wu et al. 2009).

The conservation of divergent plants is important from the points of views of biology, ecology, and breeding. Therefore, seeds have been stocked as genetic resources in several genetic resource centers and gene banks, e.g., the National BioResource Project (Kurata et al. 2010) and the Global Crop Diversity Trust (Swaminathan 2009). In such genetic resource centers, classification and identification of the genetic resources are important for the management of the stocks. The Kihara Institute for Biological Research (KIBR), Yokohama City University, Japan, is also a genetic resource center for Capsicum spp. and has kept approximately 800 lines collected from the center of origin of Capsicum, i.e., Central and South America. The species of the Capsicum stocks have been carefully classified according to the 12 criteria of the standardized phenotypic indexes of the International Plant Genetic Resource Institute, Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, and Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza of Costa Rica (IPGRI, AVRDC, and CATIE 1995). However, misidentification of species has sometimes occurred because phenotypic traits are often altered by environmental conditions. In addition, phenotypic classification using indexes requires skilled labor, time, and large fields in which to grow the plants. Consequently, this method is expensive and often impractical.

DNA sequence polymorphism is reliable, because it is not affected by environmental conditions. Furthermore, analysis of DNA polymorphism is a low-cost approach to the classification of species due to its requirements of fewer samples and less time and labor. The genetic diversity of the genus Capsicum has been investigated using DNA markers, mainly random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers (Oyama et al. 2006; Paran et al. 1998; Rodriguez et al. 1999). Such fingerprinting methods detect multi-locus polymorphism at the same time. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers have also been used to identify Capsicum species (Jeong et al. 2010; Jung et al. 2010). SNP markers generally identify bi-allelic polymorphisms. The transferability of SNP markers to other species or lines is less than that of other marker systems. Therefore, for SNP analysis, large numbers of markers are generally required for diversity analysis. Simple sequence repeat (SSR), or microsatellite, markers detect differences in the lengths of mono- to hexa-nucleotide repeat sequences. SSR markers constitute a useful tool for genetic diversity analysis, in that they enable multi-allele detection, are highly transferable across species, and are flexible enough so that they can be used with various laboratory systems (Kalia et al. 2011). SSR markers can be classified into two categories: genomic SSRs and EST–SSRs, which are designed from whole-genome and mRNA transcript sequences, respectively (Kalia et al. 2011). EST–SSRs can be expected to have greater transferability between species/genera than genomic SSRs, since gene-coding regions are more likely to be conserved among related species/genera. In Capsicum, SSR markers developed from ESTs and SSR-enriched genomic libraries have been applied to the construction of linkage maps (Minamiyama et al. 2006; Yi et al. 2006). In addition, short and standardized DNA regions, i.e., “barcodes”, have been used as a tool for species identification (Hebert et al. 2003). In plants, the matK and rbcL loci in plastid DNA have been proposed as barcodes (CBLO Plant Working Group 2009).

To characterize the genetic diversity of the Capsicum lines stocked in the KIBR, we performed polymorphism analysis with EST–SSR markers and the plastid DNA barcode sequences. The primers for the EST–SSR markers were designed based on flanking regions of SSRs identified in publicly available ESTs of C. annuum. A BLAST search to the tomato genome was conducted using the ESTs from which these primers were designed (The Tomato Genome Consortium 2012). Based on this search, 96 EST–SSR markers, which spanned the entire tomato genome, were selected for the polymorphism analysis of Capsicum stocks. In addition, matK and rbcL barcode sequences from plastid DNA were also analyzed. The genetic diversity of the Capsicum spp. was therefore characterized by both EST–SSR marker-based analyses and sequencing of plastid DNA.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

A total of 186 samples of Capsicum genetic resources, consisting of 30 C. annuum, 21 C. baccatum, 85 C. chinense, 25 C. frutescens, one C. pubescens, and 24 Capsicum lines for which species were not identified, were selected from the active stocks of the KIBR. In addition, samples from five local Japanese landraces (C. annuum: Fushimi-Amanaga, Ougon, Shishi-Togarashi, and Takanotsume; and C. frutescenes: Okinawa-Togarashi) and one globally-cultivated line (C. frutescenes: Tabasco) were also used. The accession numbers and the countries of origin of the samples are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Development, similarity searches, and genotyping of EST–SSR markers

EST sequences of C. annuum were obtained from the NCBI database in April 2010 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Primers for the EST–SSR markers were designed from the flanking sequences of di-, tri-, or tetra-nucleotide SSR motifs as described in our previous study (Koilkonda et al. 2012; Shirasawa et al. 2010; Shirasawa et al. 2011).

These EST sequences were subjected to a tBLASTx (Altschul et al. 1997) search of the tomato genome sequence SL2.30 (http://solgenomics.net), which was the latest version at the time of data analysis. These sequence similarities were judged to be significant when the E-value was <1e−50.

For each sample, genomic DNA was isolated from leaves using the DNeasy Plant mini prep kit (Qiagen). DNA concentration for each sample was determined using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific). PCR and subsequent fluorescent fragment analysis were performed as described in Shirasawa et al. (2010). The expected heterozygosity (HZ) of each marker was calculated using the following formula:

where p i is the frequency of the ith of n alleles.

Sequencing of matK and rbcL genes

The universal primers (5′-CGTACAGTACTTTTGTGTTTACGAG-3′ and 5′-ACCCAGTCCATCTGGAAATCTTGGTTC-3′ for matK, and 5′-ATGTCACCACAAACAGAGACTAAAGC-3′ and 5′-GTAAAATCAAGTCCACCRCG-3′ for rbcL) were used to amplify DNA fragments from the chloroplast matK and rbcL genes (CBLO Plant Working Group 2009). PCR reactions were performed using 0.5 ng genomic DNA in each 5-μl reaction. In addition to template DNA, PCR reaction mixes contained 1× PCR buffer (Bioline, UK), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.04 U BIOTAQ DNA polymerase (Bioline, UK), 0.2 mM dNTPs, and 0.8 μM of each primer. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 1 min initial denaturation at 94 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s annealing at 55 °C, and 1 min extension at 72 °C; and 3 min final extension at 72 °C. The amplified DNAs were treated with the ExoSAP-IT kit (GE Healthcare), which cleans up the reaction by dephosphorylating dNTPs and degrading primers that were not incorporated into the PCR products. These products were then used as templates for bidirectional sequencing analysis using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) and the DNA sequencer ABI 3730xl (Applied Biosystems).

Clustering analysis based on the EST–SSR markers

The genetic distances and Jaccard’s similarity coefficients of all combinations of any two samples were calculated from the genotypic data using GGT2 software (van Berloo 2008). A dendrogram of the samples was established using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA5 software (Tamura et al. 2011).

Results

Features of SSRs from ESTs

A total of 118,060 EST sequences of C. annuum were obtained from the NCBI DNA database. After in silico data mining, 5,751 non-redundant EST–SSR markers were generated and designated as CaES (C. a nnuum EST–SSR) markers, out of which 75 were the same loci as reported by Yi et al. (2006) (Supplementary Table S2). Of the SSR motifs identified in the CaES markers, 4,311 (75.0 %) were trinucleotide repeats, 557 (9.7 %) were dinucleotide repeats, and 882 (15.3 %) were tetranucleotide repeats (Supplementary Fig. S1).

The distributions of the EST–SSR markers on the tomato genome were investigated using BLAST. Of the 5,751 EST sequences from which the SSR primers were designed, 2,245 (39.0 %) showed significant similarity to the tomato genome sequences (SL2.30), while the positions of the mapped C. annuum ESTs on the tomato genome were highly biased (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S2).

Map positions of the CaES markers on the tomato genome. The tomato chromosomes (T01–T12) are indicated in physical length. Vertical bars on the left side of the chromosomes show the heterochromatic regions. Horizontal lines on the chromosomes indicate the positions of the CaES markers; those analyzed in this study are shown with marker names. Descriptions in parentheses following the marker names indicate the marker types: I codominant polymorphic markers, II mixture of codominant and dominant polymorphic markers, III monomorphic markers, IV dominant polymorphic markers, na no amplification or multiple bands

Genotyping of the 192 lines using the 96 EST–SSR markers

Of the 2,245 mapped EST–SSR markers, 96 were selected for the diversity analysis of the 192 pepper samples to cover the tomato chromosome with constant intervals (eight markers per chromosome) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S2). Because 19 of the 96 selected markers gave no PCR amplicons and multiple bands, these markers were eliminated from the following analysis. The other 77 markers, which yielded one or two PCR amplicons, each of which was assumed to be amplified from a single locus, were classified into four types: markers generating polymorphic DNA fragments in all of the samples (codominant polymorphic markers, type I); markers generating polymorphic DNA fragments or no fragments (mixture of codominant and dominant polymorphic markers, type II); markers generating monomorphic DNA fragments in all of the samples (monomorphic markers, type III); and markers generating monomorphic DNA fragments or no fragments (dominant polymorphic markers, type IV). The numbers of types I, II, III, and IV markers were 16, 27, 17, and 17, respectively.

The average number of alleles per marker in the 43 codominant polymorphic markers (types I and II) was 3.6 alleles, ranging from 2 to 26 (Supplementary Table S2). Sixteen markers generated two alleles, while a single marker (CaES0089) generated 26 alleles. The average HZ value in the codominant markers (types I and II) was calculated as 0.30, ranging from 0.01 (CaES2489) to 0.89 (CaES0089) (Supplementary Table S2). Both the average number of alleles and the average HZ value were higher for type II markers (4.2 alleles/loci, HZ = 0.35) than for type I markers (2.8 alleles/loci, HZ = 0.21). Among the dominant markers (types II and IV), the average number of samples exhibiting the null allele was 17.1, ranging from just a single null allele for each of 14 markers to 167 null alleles for CaES4613 (Supplementary Table S2).

Genetic distances and clustering of the 192 Capsicum lines

The genetic distances between all combinations of any two lines were investigated based on the genotyping data of the 60 informative markers (types I, II, and IV). The genetic distances among the 192 lines ranged from 0.00 to 0.39. A dendrogram was constructed, revealing 192 lines grouped into four clusters (Fig. 2). The four clusters correlated with species, with a few exceptions, and were designated Cluster A (C. annuum), Cluster B (C. baccatum), Cluster C (C. chinense), and Cluster F (C. frutescens) (Table 1; Supplementary Tables S1, S3). Cluster A consisted of 20 C. annuum, one C. baccatum, and six Capsicum spp. from the KIBR genetic resource center. Four C. annuum landraces, viz., Ougon, Fushimi-Amanaga, Shishi-Togarashi, and Takanotsume, also belonged to Cluster A. Cluster B comprised 20 C. baccatum, four C. annuum, one C. chinense, and one Capsicum spp. Cluster C, the largest cluster of the four, consisted of 78 C. chinense, seven C. frutescens, three C. annuum, and 13 Capsicum spp. Cluster F comprised 17 C. frutescens, five C. chinense, one C. annuum, three Capsicum spp., and two C. furutescens landraces, Okinawa-Togarashi and Tabasco. C. pubescens was located on the independent branch. Two C. annuum (KC139 and KC751), one C. chinense (KC262), one C. furutescens (KC515), and one Capsicum spp. (KC513) were not classifiable into any of the four clusters.

Sequence analysis of the chloroplast genes, matK and rbcL

DNA fragments were amplified from all 192 Capsicum lines with primers located within the two chloroplast genes, matK and rbcL. The sizes of the amplicons for matK and rbcL were 837 and 553 bp, respectively, excluding primer sequences.

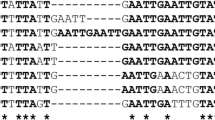

In the matK sequencing analysis, two SNPs were found at the 129th (C/A) and the 312th positions (T/C) (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). Of the 192 lines, 166 showed genotypes of C and T at the 129th and 312th positions, respectively. On the other hand, the remaining 26 samples exhibited A and C genotypes at the SNP sites. No other combinations of the SNPs were observed in the 192 samples. In the rbcL, on the other hand, one SNP (A/G) was found at the 392nd position (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). Out of the 192 lines, 136 showed A on the SNP site, whereas the other 56 samples exhibited G.

In total, three haplotypes were found in the plastid DNA of the 192 lines (Table 2). The haplotype CTA, that is, C and T at the 129th and the 312th positions of matK, respectively, and A in the rbcL, was found in Clusters C and F and four lines of Cluster A, viz., KC539, KC793, KC795, and Takanotsume, while the haplotypes CTG and ACG were predominantly specific to Clusters A and B, respectively.

Identification of alleles specific to each cluster

By calculating the genotype frequencies of the 77 informative EST–SSRs, 19 genotypes were found to be specific to one of the four clusters (Table 3; Supplementary Table S4). Three genotypes of three markers were specific to Cluster A: a 102-bp fragment of CaES2655, a 166-bp fragment of CaES4192, and a 624-bp fragment of CaES5301 were found in 87, 97, and 90 % of the lines belonging to Cluster A, but were rarely seen in samples from the other clusters (between 0 and 4 %). On the other hand, 10 genotypes, of which one was the plastid DNA gene, matK, were detected in 89–100 % of the samples from Cluster B and were rarely found in samples classified as falling within the other clusters (between 0 and 6 %). In addition, two and four genotypes were specific to Clusters C and F, respectively.

Discussion

In the EST–SSR marker analysis, Capsicum lines from five species were classified into four clusters. The five species represented were C. annuum (Cluster A), C. baccatum (Cluster B), C. chinense (Cluster C), C. frutescens (Cluster F), and C. pubescens, which was represented by a branch rather than a cluster (Fig. 2). Although most of the samples could be classified according to species cluster, 22 samples did not fall into any obvious cluster (Table 1; Fig. 2). Based on the EST–SSR marker analysis, it was found that C. chinense and C. frutescens were closely related to C. annuum, and C. baccatum was distant from the other four species. This result confirmed previous reports based on isozyme, plastid DNA, and SNP analyses as well as morphological and cytogenetic analyses (Jarret 2008; Jeong et al. 2010; Walsh and Hoot 2001; and references therein).

The haplotypes of the plastid DNA of 22 samples fell into different clusters from those of their supposed species, as determined based on morphological traits (Supplementary Table S3). These haplotypes matched a dendrogram constructed from the EST–SSR marker sequences (Supplementary Table S1). This mismatch between the cluster and species name was also confirmed by AFLP analysis (Kim and Ban unpublished data). Two possibilities were considered for the mismatch between the classifications based on morphological traits and those based on DNA sequence. The first was misclassification of species based on morphological traits. Usually, classification of Capsicum species based on morphology is carried out by investigating characters of flowers, leaves, and fruits (IPGRI, AVRDC and CATIE 1995), but classification by this method is sometimes ambiguous. This is especially true for C. chinense and C. frutescens, since the morphological characteristics of the flowers are similar in these two species (Ishii and Ban unpublished data). Misclassifications between these two species are therefore more frequent than those between other species (Fig. 2; Table 1). Another possibility is genome introgression between different species. Because Capsicum can easily cross between species due to interspecific compatibilities, a small portion of alien genome might easily become fixed in both natural and field conditions. However, introgressed genomic regions seldom affect morphological traits, and only a few specific loci dramatically change plant phenotypes, e.g., plant height, number of fluorescent panicles, and fruit shape and size (Ashikari et al. 2005; Rodríguez et al. 2011). Therefore, such genomic introgressions would not be expected to result in changes in morphological characteristics that would lead to the observed mismatched classifications.

The euchromatic regions of the tomato genome were well represented by the CaES markers (Fig. 1), because analysis using a high-density genetic linkage map (Shirasawa et al. 2010) revealed that 1,792 EST–SSRs were in the gene-rich euchromatic regions (1 EST–SSR/130 kb), and 453 were in the gene-poor heterochromatic regions (1 EST–SSR/1,200 kb). In the family Solanaceae, comparative genomics have been advanced by using the conserved orthologous set II markers commonly mapped onto the linkage maps of different species (Wu et al. 2009; Wu and Tanksley 2010). Between pepper and tomato, comparative genomic study has revealed that the two species share 35 conserved synteny segments (Wu et al. 2009). Therefore, it might be possible to estimate the positions of the CaES markers on the Capsicum genome using the positions of the CaES markers on the tomato genome. This would greatly help the construction of high-density genetic linkage maps covering the whole genome of Capsicum. Alternatively, a combination of bin maps, using minimum sets of the marker loci to cover the genome generally, and fine maps, targeting specific loci using the CaES markers, would be useful.

The two “barcode” plastid genes, rbcL and matK, were insufficient to distinguish the tested Capsicum species. In the present study, the clusters C and F, which mainly consisted of C. chinense and C. frutescens, respectively, were not separated by the “barcode” sequences. Moreover, plastid DNA might not be suitable as a barcode in crops because of interspecific crossing. F1 hybrids from interspecific crossings are often used for cultivars due to their hybrid vigor, and plastid DNA cannot distinguish these hybrids from their maternal plants due to identical cytoplasm. Isogenic lines and introgression lines would also be indistinguishable from their maternal parents on the basis of plastid DNA. Our results indicated that four samples, viz., KC539, KC793, KC795, and Takanotsume, might be derived from such hybridizations between C. annuum as a paternal parent and either C. chinense or C. frutescens as a maternal parent because their nuclear and cytoplasmic genotypes belonged to Cluster A and Clusters C or F, respectively (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S1). To overcome this problem, the intron sequence of the waxy gene encoded in the nuclear genome was proposed as a barcode (Jarret 2008; Walsh and Hoot 2001). However, the utility of waxy is strikingly limited because it has not been identified in all plant species. On the other hand, EST–SSR markers have also been useful for species identification (Table 3). A substantial amount of RNA sequence data has accumulated in public DNA databanks (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank) since the production of transcribed sequence data is easily accomplished using next-generation sequencers. Advances in in silico searching of polymorphic SSR by comparative sequence data analysis (Shirasawa et al. 2012; polySSR: Tang et al. 2008; SSRpoly: http://acpfg.imb.uq.edu.au/ssrpoly.php) will accelerate the process of finding polymorphic SSR candidates. To correctly evaluate the genetic diversity of the samples in this study, polymorphic analysis of both nuclear and plastid genomes would be effective.

The CaES markers derived from EST sequences of C. annuum worked efficiently not only in C. annuum but also in C. baccatum, C. chinense, C. frutescens, and C. pubescens. In our previous study in tomato, 85 % of the EST–SSR markers derived from sequences of S. lycopersicum successfully amplified specific DNAs in a different species, S. pennellii (Shirasawa et al. 2010). In Brassica, the transferability of B. rapa EST–SSR markers between relatives was calculated as 43–100 %, depending on genetic distance (Ramchiary et al. 2011). In the case of Capsicum in this study, the transferability of the EST–SSR markers was 100 %, suggesting that nucleotide sequences in gene-coding regions of Capsicum species were substantially conserved.

Of the SSR motifs in the CaES markers, the most abundant motifs were poly (AAG)n (17.0 %), poly (ATC)n (11.3 %), poly (AAC)n (10.1 %), and poly (AGC)n (8.7 %) (Supplementary Fig. S1). This tendency almost matched that in tomato: poly (AAG)n (22.5 %), poly (ATC)n (12.1 %), poly (AGC)n (9.3 %), and poly (AAC)n (8.4 %) (Shirasawa et al. 2010). On the other hand, the abundant motifs in the EST–SSR markers in peanut were poly (AAG)n (23.7 %), poly (AG)n (19.8 %), poly (AAT)n (8.2 %), and poly (GGT)n (7.4 %) (Koilkonda et al. 2012), and those in radish were poly (AAG)n (21.4 %), poly (GGA)n (14.2 %), poly (ATC)n (10.1 %), and poly (AAC)n (8.0 %) (Shirasawa et al. 2011). While the prominent motif throughout the four species is poly (AAG)n, which is consistent with the previous report (Tóth et al. 2000), the distributions of the SSR motifs differed at the level of order but were similar to those of the family Solanaceae.

The present study used EST–SSR markers developed from publicly available EST sequences to reveal the relationships between Capsicum lines from the KIBR. Moreover, the positions of the markers on the tomato genome sequences were deduced. These markers and related information will contribute not only to species identification but also further QTL analysis, genome-wide association studies, and gene mapping towards the development of several attractive traits of Capsicum, e.g., fruit colors, shapes, sizes, and cellular components, in combination with morphological, biochemical, and histochemical methods.

References

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI–BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402

Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin S, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A, Angeles ER, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M (2005) Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 309:741–745

CBLO Plant Working Group (2009) A DNA barcode for land plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:12794–12797

Hebert PD, Cywinska A, Ball SL, deWaard JR (2003) Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc Biol Sci 270:313–321

IPGRI, AVRDC and CATIE (1995) Descriptors for Capsicum (Capsicum spp.). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome

Jarret RL (2008) DNA barcoding in a crop genebank: the Capsicum annuum species complex. Opin Biol J 1:35–42

Jeong HJ, Jo YD, Park SW, Kang BC (2010) Identification of Capsicum species using SNP markers based on high resolution melting analysis. Genome 53:1029–1040

Jung J, Park SW, Liu WY, Kang BC (2010) Discovery of single nucleotide polymorphism in Capsicum and SNP markers for cultivar identification. Euphytica 175:91–107

Kalia RK, Rai MK, Kalia S, Singh R, Dhawan AK (2011) Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica 117:309–334

Koilkonda P, Sato S, Tabata S, Shirasawa K, Hirakawa H, Sakai H, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Wada T, Kishida Y, Tsuruoka H, Fujishiro T, Yamada M, Kohara M, Suzuki S, Hasegawa M, Kiyoshima H, Isobe S (2012) Large-scale development of expressed sequence tag-derived simple sequence repeat markers and diversity analysis in Arachis spp. Mol Breed 30:125–138

Kurata N, Satoh H, Kitano H, Nagato Y, Endo T, Sato K, Akashi R, Ezura H, Kusaba M, Kobayashi M, Nitasaka E, Kasai F, Yamazaki Y, Yoshimura A (2010) NBRP, National Bioresource Project of Japan and plant bioresource management. Breed Sci 60:461–468

Lee JM, Nahm SH, Kim YM, Kim BD (2004) Characterization and molecular genetic mapping of microsatellite loci in pepper. Theor Appl Genet 108:619–627

Minamiyama Y, Tsuro M, Hirai M (2006) An SSR-based linkage map of Capsicum annuum. Mol Breed 18:157–169

Miura Y, Inoue T, Minamiyama Y, Kubo N (2012) An SSR-based genetic map of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) serves as an anchor for the alignment of major pepper maps. Breed Sci 62:93–98

Moscone EA, Baranyi M, Ebert I, Greilhuber J, Ehrendorfer F, Hunziker AT (2003) Analysis of nuclear DNA content in Capsicum (Solanaceae) by flow cytometry and Feulgen densitometry. Ann Bot 92:21–29

Oyama K, Hernández-Verdugo S, Sánchez C, González-Rodríguez A, Sánchez-Peña P, Garzón-Tiznado JA, Casas A (2006) Genetic structure of wild and domesticated populations of Capsicum annuum (Solanaceae) from northwestern Mexico analyzed by RAPDs. Genet Resour Crop Evol 53:553–562

Paran I, Aftergoot E, Shifriss C (1998) Variation in Capsicum annuum revealed by RAPD and AFLP markers. Euphytica 99:167–173

Paran I, van der Voort JR, Lefebvre V, Jahn M, Landry L, van Schriek M, Tanyolac B, Caranta C, Chaim AB, Livingstone K, Palloix A, Peleman J (2004) An integrated genetic linkage map of pepper (Capsicum spp.). Mol Breed 13:251–261

Paran I, Ben-Chaim A, Kang BC, Jahn M (2007) Capsicums. In: Cole C (ed) Genome mapping and molecular breeding in plants, vol 5. Springer, New York, pp 209–226

Ramchiary N, Nguyen VD, Li X, Hong CP, Dhandapani V, Choi SR, Yu G, Piao ZY, Lim YP (2011) Genic microsatellite markers in Brassica rapa: development, characterization, mapping, and their utility in other cultivated and wild Brassica relatives. DNA Res 18:305–320

Rodriguez JM, Berke T, Engle L, Nienhuis J (1999) Variation among and within Capsicum species revealed by RAPD markers. Theor Appl Genet 99:147–156

Rodríguez GR, Muños S, Anderson C, Sim SC, Michel A, Causse M, Gardener BB, Francis D, van der Knaap E (2011) Distribution of SUN, OVATE, LC, and FAS in the tomato germplasm and the relationship to fruit shape diversity. Plant Physiol 156:275–285

Shirasawa K, Asamizu E, Fukuoka H, Ohyama A, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S, Sasamoto S, Wada T, Kishida Y, Tsuruoka H, Fujishiro T, Yamada M, Isobe S (2010) An interspecific linkage map of SSR and intronic polymorphism markers in tomato. Theor Appl Genet 121:731–739

Shirasawa K, Oyama M, Hirakawa H, Sato S, Tabata S, Fujioka T, Kimizuka-Takagi C, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Kato M, Kishida Y, Kohara M, Takahashi C, Tsuruoka H, Wada T, Sakai T, Isobe S (2011) An EST–SSR linkage map of Raphanus sativus and comparative genomics of the Brassicaceae. DNA Res 18:221–232

Shirasawa K, Koilkonda P, Aoki K, Hirakawa H, Tabata S, Watanabe M, Hasegawa M, Kiyoshima H, Suzuki S, Kuwata C, Naito Y, Kuboyama T, Nakaya A, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Kato M, Kawashima K, Kishida Y, Kohara M, Kurabayashi A, Takahashi C, Tsuruoka H, Wada T, Isobe S (2012) In silico polymorphism analysis for the development of simple sequence repeat and transposon markers and construction of linkage map in cultivated peanut. BMC Plant Biol 12:80

Swaminathan MS (2009) Gene banks for a warming planet. Science 325:517

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739

Tang J, Baldwin SJ, Jacobs JM, Linden CG, Voorrips RE, Leunissen JA, van Eck H, Vosman B (2008) Large-scale identification of polymorphic microsatellites using an in silico approach. BMC Bioinform 9:374

The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium (2011) Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475:189–195

The Tomato Genome Consortium (2012) The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485:635–641

Tóth G, Gáspári Z, Jurka J (2000) Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res 10:967–981

van Berloo R (2008) GGT 2.0: versatile software for visualization and analysis of genetic data. J Hered 99:232–236

Walsh BM, Hoot SB (2001) Phylogenetic relationships of Capsicum (Solanaceae) using DNA sequences from two noncoding regions: the chloroplast atpB-rbcL spacer region and nuclear waxy introns. Int J Plant Sci 162:1409–1418

Wu F, Tanksley SD (2010) Chromosomal evolution in the plant family Solanaceae. BMC Genomics 11:182

Wu F, Eannetta NT, Xu Y, Durrett R, Mazourek M, Jahn MM, Tanksley SD (2009) A COSII genetic map of the pepper genome provides a detailed picture of synteny with tomato and new insights into recent chromosome evolution in the genus Capsicum. Theor Appl Genet 118:1279–1293

Yi G, Lee JM, Lee S, Choi D, Kim BD (2006) Exploitation of pepper EST–SSRs and an SSR-based linkage map. Theor Appl Genet 114:113–130

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gion Ajiko Co., Ltd. (Kyoto, Japan) for providing the cultivar Ougon. This work was supported by the Kazusa DNA Research Institute Foundation, the Kihara Institute for Biological Research, and the Yamazaki Spice Promotion Foundation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Nucleotide sequence data reported are available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession numbers AB721552–AB721935. Information on the DNA markers and the genotypes of the investigated plants are available at the Kazusa Marker Database (http://marker.kazusa.or.jp).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirasawa, K., Ishii, K., Kim, C. et al. Development of Capsicum EST–SSR markers for species identification and in silico mapping onto the tomato genome sequence. Mol Breeding 31, 101–110 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-012-9774-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-012-9774-z