Abstract

Multibeam echosounders are becoming widespread for the purposes of seafloor bathymetry mapping, but the acquisition and the use of seafloor backscatter measurements, acquired simultaneously with the bathymetric data, are still insufficiently understood, controlled and standardized. This presents an obstacle to well-accepted, standardized analysis and application by end users. The Marine Geological and Biological Habitat Mapping group (Geohab.org) has long recognized the need for better coherence and common agreement on acquisition, processing and interpretation of seafloor backscatter data, and established the Backscatter Working Group (BSWG) in May 2013. This paper presents an overview of this initiative, the mandate, structure and program of the working group, and a synopsis of the BSWG Guidelines and Recommendations to date. The paper includes (1) an overview of the current status in sensors and techniques available in seafloor backscatter data from multibeam sonars; (2) the presentation of the BSWG structure and results; (3) recommendations to operators, end-users, sonar manufacturers, and software developers using sonar backscatter for seafloor-mapping applications, for best practice methods and approaches for data acquisition and processing; and (4) a discussion on the development needs for future systems and data processing. We propose for the first time a nomenclature of backscatter processing levels that affords a means to accurately and efficiently describe the data processing status, and to facilitate comparisons of final products from various origins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exploration of the ocean floor relies widely on the use of underwater acoustics for seafloor mapping (Bourillet et al. 1996; Brown et al. 2012; Pratson and Edwards 1996). The present day capabilities of seafloor-mapping sonars reflects several decades of innovative design and development of acoustic technology adapted for mapping across the vast range of ocean depths. These sonars rely on the transmission of a sound pulse and its backscattering by the seafloor (Lurton 2010). They have been used for almost a century for bathymetric and hydrographic purposes, using the time delay and angle direction of the seafloor echoes. A more recent development which arose from the use of seafloor-mapping sonars is the use of the backscatter strength (BS) as an observable quantity, which can provide information pertinent to the nature and the structure of the target seafloor (Brown and Blondel 2009; de Moustier 1986).

Up until recently, however, seafloor backscatter applications were considered rather exploratory techniques and mainly remained within the domain of the scientific community (e.g. Augustin et al. 1996; Brown et al. 2011a; Dartnell and Gardner 2004; Clarke et al. 1997; Jackson et al. 1986; Lamarche et al. 2011). Seafloor backscatter data have long been considered as a by-product of multibeam bathymetry and, at best, as a qualitative first-order indicator of the seafloor sediment type. The backscatter intensity relates to volume heterogeneity (sediment grain-size, bioturbation, geological layering) and interface roughness (seabed substrate, micro-topography, landforms, etc.). The backscatter signal therefore provides qualitative and quantitative information on the composition of the substrate or the seafloor conditions (e.g. Clarke et al. 1996; Jackson and Briggs 1992). Furthermore, because the seafloor is the physical support of the benthic habitat, backscatter data has the potential to provide information related to fauna, flora and biodiversity (e.g. Anderson et al. 2008; Brown and Blondel 2009; Brown et al. 2011b; Cochrane and Lafferty 2002; Lamarche et al. 2016). Regional-scale quantitative applications of backscatter data for habitat mapping are technically challenging (Brown and Blondel 2009; Dartnell and Gardner 2004; Lamarche et al. 2011; Lucieer and Lamarche 2011). However, a key potential for backscatter data lay in its ability to provide a proxy for substrates and benthic habitat.

The marine industry has recently acknowledged the potential associated with backscatter data, as practical benefits arise for operations related to offshore engineering and mineral resource exploration and exploitation (e.g. Gutierrez et al. 2015; Lucieer et al. 2015; Medialdea et al. 2008). This potential, in parallel with the need for objective and quantitative information on the seafloor from remotely-sensed data has resulted in a line of research and development that has developed acquisition, processing and interpretation of the backscatter signal as quantitative tools for geological and environmental purposes (Lurton and Lamarche 2015).

Nevertheless, there is today a lack of commonly accepted acquisition procedures and processing methodologies of backscatter data recorded with multibeam echosounders (MBES) for seafloor surveys (Lurton and Lamarche 2015). Similarly, there are also gaps in the documentation and literature pertinent to backscatter interpretation, at-sea survey operations, and dedicated data processing.

Worldwide the seafloor has been mapped using a variety of systems and platforms (surface vessels and underwater vehicles) and operators have applied a range of operational procedures and principles. Likewise, data processing is undertaken using a variety of software, whether commercially available or freeware (Le Gonidec et al. 2003; Schimel et al. 2015). Hence, a lack of consistency in the backscatter data has been identified between datasets recorded by systems built by different manufacturers, as well as for successive generations of sonars from the same manufacturer. Furthermore, inconsistencies have been observed for the performance continuity of the same system over its life cycle, and in results from various software suites applying the same processing operations on the same data. Although empirically acknowledged, these problems have never been thoroughly addressed, whether by scientists or manufacturers; they are increasing because of the rapidly evolving technology and are an impediment to the progress of backscatter good use and proper interpretation. Hence, in order to mitigate the possible discrepancies between data obtained by different sonar systems or processing software, a more stringent consensual definition of procedures for instrument calibration is required, as well as standardization applicable to first-level operations of backscatter data processing (Brown et al. 2015; Rice et al. 2015).

In response to these issues, the GeoHab community—which includes some of the most active users of backscatter data across science, industry and government agencies in the field of marine habitat mapping—launched in 2013 the Backscatter Working Group (BSWG; see http://geohab.org/BSWG/) with the vision that “Backscatter data acquired from differing sonar systems, or processed using differing software, generate consistent values over the same area under the same conditions, are scientifically meaningful and usable by end-users from all application domains”. These domains include (but are not limited to) geoscience, environment, hydrography, industry, fisheries, monitoring, and cultural assessment. One major task of the BSWG was therefore to provide best practice guidelines for the acquisition and processing of backscatter data from seafloor-mapping sonars, and recommendations for the improvement and further development of such acquisition systems and processing tools.

This paper is an introduction to the present special issue on Seafloor Backscatter Data From Swath-Mapping Echosounders: From Technological Development to Novel Applications. The purposes are to (1) present an overview of the context of seafloor backscatter related research to date; (2) discuss the rationale and feasibility of the main recommendations from the BSWG; and (3) provide an insight into the future of marine acoustic backscatter-related science. We discuss four overarching recommendations that emerged through the discussions of the BSWG: (1) sonar calibration, which although not novel per se, covers issues from procedures to be implemented at manufacturing time to those required in a more systematic manner prior to any survey; (2) data acquisition issues and protocols, including the need to deal with multiple configurations and strategies depending on the survey purpose, and the development of best practice specifically for acquisition of backscatter data jointly with the more traditional bathymetric operations; (3) methods and tools for backscatter data processing, for which a need for some homogenization has been identified, at least for the fundamental operations; and (4) system design and configuration, including the implementation of backscatter-dedicated functionalities in existing sonars and possibly the development of future specialized systems. Finally, we propose for the first time a nomenclature of backscatter processing levels, which affords a means to accurately and efficiently describe the status of the processed data, thus facilitating comparison of final products regardless of their origins.

Context of seafloor backscatter research

Seafloor backscatter measured by sonar

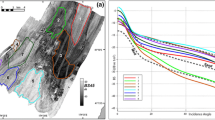

Active sonars are built on common working principles: transmission of a short signal, and reception, detection and measurement of its returned echo from a target whether it be the seafloor, fish schools, submarines, wrecks, gas bubbles or seaweeds. All seafloor-mapping sonars rely on the backscatter of a controlled sound wave by the seafloor interface (Fig. 1); the received echo being used for seafloor detection, bathymetric measurement, imaging and characterization (Lurton 2010).

Fundamental principle of backscatter measurement and interpretation. A swath pattern (a) of incidence waves (yellow c, e) generates reflection (dark blue e), scattered (light blue e), backscattered (red c–f) and transmitted (green e) waves. The intensity of the backscattered echo is dependent on the incidence angle on the seafloor (b). Soft or flat seafloor (c) generates much different angular dependence (d) than rough interface (e, f)

The signal at the sonar’s receiving array provides two fundamental features: the echo time delay and the echo intensity. The former is equivalent to the range between the sonar and the target; associated to angle information, it is mainly used to provide measurements of the water depth, detect military targets or localize fish schools. This was the primary purpose of sonars when they appeared over a century ago (see review in Mayer 2006). Bathymetry measurements from sonar are straightforward, at least in principle, as they use geometrical analysis of the recorded echo delays and arrival angles.

On the other hand, using the echo intensity to obtain objective information on the nature of the seafloor relates to much more complex physical processes. While the intensity of the backscatter signal is relative to the target characteristics and acquisition geometry, the detailed phenomena depend on a combination of acoustic and geophysical processes, accounting for both transmitting and receiving/processing characteristics of the sonar and the various physical phenomena (transmission, refraction, absorption, scattering) happening both in the water and at the seabed (Jackson and Richardson 2007).

The first generation of MBES dedicated to seafloor-mapping came into use in the late 1970s (Renard and Allenou 1979). These pioneer systems made little or no explicit use of the echo intensity, as their main objective was accurate bathymetry measurements, and their technical characteristics did not make it easy to observe reflectivity variations (Lurton 2010). In parallel, side-scan sonars (formerly issued in the 1960s) were able to produce seafloor images of high quality, in which the high-resolution geometrical imaging of the scenes was embellished by echo intensity modulations, giving a supplementary tool for interpretation, such as in roughly distinguishing sediments of different types (e.g., Belderson et al. 1972; Blondel and Murton 2000; Laughton 1981; McRea et al. 1999; Pratson and Edwards 1996).

The potential of the echo intensity of MBES was recognized sometime after the occurrence of the first bathymetric surveys (de Moustier 1986). Significant progress was achieved with the arrival of digital processing, and the design of seafloor-mapping sonars with hardware of increasing quality (Bourillet et al. 1996; Calder 2003; De Moustier and Matsumoto 1993; Fonseca and Calder 2006; Foote et al. 1987; Le Gonidec et al. 2003). A breakthrough occurred in the early 1990s, when Simrad (Today: Kongsberg Maritime) issued multibeam echosounders with a dedicated “sonar image” acquisition capability (Simrad 1992), designed to complement the bathymetry measurement (Fig. 2) by providing reflectivity mosaics co-located with the classical bathymetric maps. This functionality was continuously improved in successive systems from Kongsberg and other manufacturers. Today, it is hard to imagine MBES data without a reflectivity component. The pictorial quality of MBES images has tremendously improved in resolution, stability and dynamics, and now compare very well with side-scan sonar images and satellite-borne scatterometer data (Elachi 1988). Likewise, in optimal conditions, the best data are able to provide objective measurements of the absolute reflective power of underwater targets, hence opening new ways to the interpretation of seafloor scenes (Kloser et al. 2010; McGonigle and Collier 2014).

One of the first backscatter mosaic acquired during the 1993 GeodyNZ survey (Collot et al. 1996) generated from Simrad (now Kongsberg) EM12 multibeam echosounder

Backscatter data processing

In order to access the backscatter information inherent to the seafloor, the raw echo features unrelated to the target need to be corrected in the recorded signal. Two types of compensations need to be applied to the signal so that (1) the characteristics of the sonar sensor per se (transmission level, reception sensitivity, beam aperture and signal duration) do not affect the estimation of the target’s backscatter strength (Urick 1983), although these contribute to the received echo intensity; and (2) the propagation losses must be corrected according to local environmental conditions and acquisition geometry. Subsequently, the corrected echo intensity can be considered as representing the seafloor effect alone, and translated into the target backscatter strength (i.e. its inherent capability for sending back acoustic energy to the sonar). This “reflectivity” characteristic relates to the mechanical characteristics of the target material and its geometrical shape and size, but also on the signal frequency and the incidence angle.

The angular dependence is a fundamental characteristic of the backscatter response (Le Chenadec et al. 2007; Clarke et al. 1997), which imply specific operations in the data processing (Augustin and Lurton 2005; de Moustier 1986; Hellequin et al. 2003; Parnum and; Gravilov 2011; Schimel et al. 2015) and complexity in their interpretation (Hasan et al. 2012; Dugelay et al. 1996; Fonseca and Mayer 2007; Huang et al. 2013; Lamarche et al. 2011; Rzhanov et al. 2012). A rough and hard seafloor interface, usually from coarse material or rocks results in isotropic scattering of the sound waves so that the average echo level depends little on incidence angle. The echo intensity recorded over the full swath width is then stable whatever the angle (Fig. 1). Conversely, a soft and flat fluid-like sediment seafloor generates a mirror-like response, for which the largest part of the intensity is reflected at normal incidence with very little scatter at oblique angles; the sonar image then shows a strong maximum in its center (at nadir), and a fast intensity decrease on the sides. Clearly, there is a continuum between these two extreme cases. Practically, the problem is complicated by the presence of scatterers either lying on the seabed, or buried in the sediments. In soft sediments, structural layering and buried heterogeneities (e.g., mineral, biological, or gaseous) contribute significantly to the overall backscatter at intermediate angles (Guillon and Lurton 2001; Jackson and Briggs 1992; Jackson and Richardson 2007; Novarini and Caruthers 1998) and may dominate in the resulting response. Since these cannot be observed separately from the seabed roughness effect, they are effectively integrated inside an equivalent global “interface backscatter”.

Intensity modulations in seafloor images caused by this backscatter dependence with angle over the swath width require specific compensations to make the graphical display easily interpretable (Augustin and Lurton 2005; Hellequin et al. 2003; Lurton et al. 1997; Parnum and; Gravilov 2011; Schimel et al. 2015). Dedicated processing operations are hence devoted to flattening the angular response so that a geologically-homogeneous flat seafloor appears at a constant reflectivity level on the processed image, whatever its original angle dependence (Augustin and Lamarche 2015; Dugelay et al. 1996). This implies that (1) the angular modulation caused by the sensor has been identified and compensated for, and (2) a hypothesis of seafloor facies homogeneity is acceptable.

Backscatter angular dependence, if correctly measured and preserved, is a powerful tool for a classification operation. The two contradictory objectives of flattening the angular response for image readability, while preserving its full angular dependence for seafloor-type interpretation, imply to accurately depict the angle characteristics of the observed scenes, which essentially depends on a correct estimation of the local bathymetry. This justifies using MBES for backscatter measurement as the sensors are able to provide simultaneously angular reflectivity and bathymetry at a comparable resolution, and inside an accurate georeferenced grid.

Spatial resolution (i.e. the signal footprint extent) of a swath seafloor-mapping sonar is a key feature in backscatter data processing and interpretation. It is given by the extent of the beam section intersecting the seafloor interface and active at one given instant; hence it is a function of both the range to the seafloor (increasing at oblique angles for a given water depth), the beam aperture (typically 1° i.e. ~2% of the sonar-target range) and the signal duration.

Backscatter interpretation

Interpretation of backscatter data in terms of “seafloor type” has not been addressed in detail by the BSWG, although a number of fundamental and practically useful elements are given in the Guidelines and Recommendations document published by the group (Lurton and Lamarche 2015). Perhaps the prime information derived from backscatter data is the acoustic facies, i.e. “the characteristics and spatial organization of seafloor patches with common acoustic responses and the measurable characteristics of this response”. Maps of acoustic facies—most often simply represented by the post-processed backscatter data—are the initial material available to scientists to interpret sediment grain size or habitat (Figs. 2, 3). Substantial efforts have been made in trying to obtain seafloor type or physical characteristics from the measurement of the backscatter level (e.g., Brown and Blondel 2009; De Moustier and Matsumoto 1993; Kloser et al. 2010; Lamarche et al. 2011; McGonigle and Collier 2014; Preston et al. 2001), in many cases according to its angle dependence (Haniotis et al. 2015). Some original applications include recognition and mapping algae (McGonigle et al. 2011), oil spills (Medialdea et al. 2008), or hydrothermal vents and seeps (Durand et al. 2006; Klaucke et al. 2008).

Example of multiple Multibeam EchoSounder (MBES) data collected in a same region with either poor or no calibration of backscatter data resulting in a non-comparable product. All data were collected using three systems EM12 (1) (from Collot et al. 1996); EM300 (2) and EM302 (all other surveys). High backscatter values in white

Although ultimately the classification of the acoustic facies as sediment classes is arguably the best practical approach today to efficiently derive substrate and habitat maps over wide areas, it is important to remember that acoustic-based systems do not provide a direct measurement of the seafloor geological or biological characteristics. Hence, the backscatter data per se does not provide unequivocal information about the substrate or habitat, where the term “habitat” captures the combination of environmental and biological conditions that promote occupancy by a given group of seabed species (Lamarche et al. 2016). Interesting experiments have been conducted to analyze the quality of habitat classification obtained from the various descriptors derived from MBES data that mix bathymetry and reflectivity measurements, showing the importance of using the angular dependence of backscatter (Hasan et al. 2014). Finally it should be emphasized that acoustic facies correspond to habitat typology only on a relative scale, and some ambiguities remain as acoustic reflectivity may not be a fine enough indicator of habitat subtleties.

Towards standardization of acquisition and processing practices

The various communities interested in using MBES data for seafloor mapping are today largely left to themselves regarding the acquisition, processing and interpretation of backscatter (Lucieer et al. 2015, 2017) with no overarching standards or best practice protocols yet established. Understanding and modeling of the backscatter phenomena still remain a specialist’s domain, as does the knowledge and understanding of the dedicated sonar functionalities. The MBES manufacturers’ instructions regarding backscatter acquisition and processing are most often succinct and usually insufficient to be directly usable for objective and quantitative interpretation. The BSWG recognized that it was timely to develop a collective synthesis in order to define needs, expectations, methods and practical procedures.

Several examples, taken from related scientific or technological disciplines suggest that such a collaborative approach could be beneficial for advancing standards and best practices, including:

-

The bathymetry/hydrography community undertook a similar initiative for sonar bathymetry applied to seafloor charting. This led the International Hydrographic Office (IHO) to define standardizations (IHO 2008) that are today agreed, regularly updated and applied worldwide. Since the same sonar technologies, especially MBES, are used for both bathymetry and backscatter measurements, some standardization should be facilitated for reflectivity-related issues, although it may not necessarily be the responsibility of the IHO.

-

The fisheries acoustics community is confronted with the issue of accurate objective estimation of biomass quantities (a mandatory requirement for defining quotas in national fishery policies), implying the definition of procedures for quantified measurements of the echoes from the water column. Fisheries acousticians have defined their own corpus of recommendations, procedures and standards (Demer et al. 2015; Foote et al. 1987), encompassing both the sonar calibration methods and the at-sea acquisition and processing of backscatter data.

-

The remote-sensing community, although focusing on different issues that those pertinent to marine sonars, has taken very seriously the issue of quantitative reflectivity measurement from space-borne radars (Chen 1984; Elachi 1988; ASAR 1998). Objective technological requirements were defined following a user needs survey (Brown et al. 1993), including calibration procedures (Freeman 1992; Luscombe and Thompson 2011) and standardization of post-acquisition processing sequence. Satellite-borne radars (Synthetic Aperture Radars and Scatterometers) are very similar structurally and functionally to MBES, although affected by much less severe constraints, in particular regarding the propagation medium effect and the acquisition geometrical configuration. The radar backscatter measurement is commonly applied to various purposes such as the monitoring of the sea-state or sea-ice, forest and agriculture mapping and control, etc. The success of these techniques and applications bodes well for similar results with seafloor-mapping sonars—keeping in mind the specific difficulties and intrinsic limitations of the latter.

The Backscatter Working Group

In response to the issues and expectations listed above, the GeoHab community decided to form the Backscatter Working Group (BSWG), during its 2013 annual meeting. This group is a fully collaborative initiative. Its mandate was to produce a comprehensive report to define needs, methods and practical procedures related to seafloor backscatter data acquisition and processing. The aim of the BSWG report (Lurton and Lamarche 2015) was twofold: (1) to provide guidelines and best practice approaches for the acquisition and processing of backscatter data from seafloor-mapping sonars, and (2) to gather and make available to stakeholders, manufacturers and end-users, a corpus of recommendations for the improvement and further development of seafloor-mapping sonar systems, improvement of backscatter data acquisition procedures, and related processing tools.

Three primary themes emerged through the work of the BSWG:

-

1.

Sonar hardware manufacturing issues, including interactions between users and manufacturers, sonar configuration and related instrument uncertainty levels, and best practice for sonar configuration focusing on backscatter;

-

2.

Data acquisition issues and protocols, including best configuration, survey purpose and strategy, as well as best practice for backscatter acquisition operations;

-

3.

Data processing approaches, ensuring consistency of results from the wide variety of existing systems and many application purposes.

More specifically, the group addressed the following points and issues:

-

Propose common terminology and definitions applicable to the physical phenomena, the processing operations, and the data at the various stages from acquisition to interpretation;

-

Summarize the fundamental notions of physical phenomena and sonar engineering at an affordable user level;

-

Review the needs expressed by users and their associated technical requirements regarding both the sonar systems and the processing software suites;

-

Provide a series of recommendations to sonar manufacturers and software developers for future development as well as to users and operators for best acquisition procedure and post-processing approaches;

To date, more than 300 users and stakeholders with various backgrounds and expertise have registered and expressed an interest in the BSWG (bswg@geohab.org), including:

-

Marine scientists with interests ranging from environmental sciences and oceanography to underwater acoustics;

-

Software developers specialized in processing of seafloor-mapping sonar data;

-

Surveyors, equipment operators, and marine operation managers;

-

Hardware engineers involved in the manufacturing of seafloor-mapping sonars.

The BSWG remains open to all people with direct or indirect interest in seafloor backscatter applications. Registered members of the group are either actively participating in the discussion and writing of the document, or following and benefiting from its progress. However the core group of authors remained stable from late 2013 and during the writing of the document (Lurton and Lamarche 2015). A first version of the complete report was edited and presented at the 2015 GeoHab conference.

The BSWG elected to limit its activity to seafloor backscatter, leaving aside other applications such as water column investigation. This decision was justified mainly by (1) the recent and rapid evolution of hardware, software and methodologies pertinent to water column from MBES, which was likely to result in obsolete information by the time the report would be published; (2) the existence of a similar project recently conducted by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in the field of fisheries sonar (Demer et al. 2015); and (3) the desire to restrict the BSWG’s tasks to be manageable.

Recommendations for an improved use of seafloor backscatter

Our recommendations for an optimized use of backscatter data are developed in four sections: (1) system and data calibration, (2) acquisition procedures, (3) data processing and interpretation, and (4) system design and documentation (Table 1). These follow closely the recommendations of the BSWG.

System and data calibration

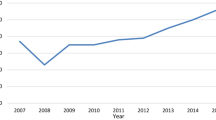

The reliability and consistency of seafloor backscatter data requires some sort of calibration of the sonar sensor (Brown et al. 2015; Foote et al. 2005; Gueriot et al. 2000; Heaton 2014; Rice et al. 2015). This is essential for comparing data issued from various systems, or for processing data from one system acquired over several years (Fig. 3) and for direct interpretation of the recorded backscatter levels. There are two types of backscatter data calibrations:

-

Absolute calibration, enabling the sonar to measure true referenced physical values of backscatter, and

-

relative calibration, ensuring self-consistency of the measurements by one system, without an absolute reference of the backscatter level.

The initial calibration of a sonar system should undoubtedly be a standard procedure undertaken at manufacturing time and therefore lies primarily under the manufacturer’s responsibility. Such a procedure includes multiple steps during manufacturing, and clearly not all manufacturers today provide enough details about their implementation and effects. Transducers and electronic modules should be measured in factory, as individual elements, in frequency response, angular directivity, level linearity, etc. for both transmission and reception. The overall response of the instrument should also be checked under factory conditions when practically feasible (e.g. very-high frequency systems in test tanks, on reference targets). Finally an overall calibration should be conducted once the sonar system has been installed on its carrier vehicle, as part of a sea-acceptance test (SAT) operation involving the customer’s technical team and operators.

Subsequent to the commissioning of a sonar, simplified calibration operations should be regularly conducted during the lifecycle of the system, and in particular prior to surveys specifically devoted to backscatter data acquisition, or where backscatter data are particularly important to overall survey objectives, akin to the current and well-accepted practice of bathymetric calibration of multibeam echosounders for hydrographic surveys (e.g. NOAA 2014). We recommend that field operators be trained for this specific purpose. Automatized and built-in test (BIST) functionalities greatly support the routine detection of unwanted changes in the system and facilitate such operations and therefore should be extended to include backscatter measurements. Importantly, regular and consistent overall calibrations should be conducted over reference seafloor areas, as well as cross-calibration with calibrated sonars for benchmarking.

We believe that the optimal practical solution for both initial and follow-up calibrations is through the use of a reference areas preliminary characterized using a calibrated sonar sensor. Ideally, these areas should be flat, smooth and geologically and acoustically homogeneous. They should be pre-surveyed in detail using a single beam echosounder calibrated within fisheries standards (Gueriot et al. 2000; Rice et al. 2015; Ladroit et al. 2017; Lurton et al. 2017). They should be ground-truthed and regularly monitored to check for stability. All the calibration results and modifications applied to the sonar should be accurately reported and recorded for future use and reference.

Acquisition procedures

Even though backscatter and bathymetry data are acquired using the same set of MBES arrays and electronics, the processing steps are distinct from each other. Unfortunately, optimal backscatter data acquisition requires specific settings that may differ from those required for optimal bathymetry data acquisition. Such settings include tools, pre-settings, and automated modes provided by manufacturers. Satisfactory acquisition of backscatter data implies that the correct settings for the signal amplitude dynamics are optimized to avoid both low signal-to-noise ratio and signal distortion and clipping due to saturation. This optimization is not systematically available in today’s systems. More generally, our recommendations are two-fold: constancy of acquisition settings and specific design of backscatter-dedicated surveys.

Constancy of acquisition settings

Acquisition settings should be kept as stable as possible, rather than using the varying, automated modes incorporated in many MBES today. Indeed most systems allow the operator to impose a single mode, optimized to the dominant conditions on a given survey, in order to minimize changes in source level, pulse duration, receiver gains, and directivity patterns that may critically affect the backscatter measurement. For the same reasons, the simplest system configuration should be chosen whenever possible (e.g. single transmitting (Tx) sector, continuous waves (CW) signals rather than frequency modulation (FM), etc.). However, such settings may not be optimal for simultaneous bathymetric data acquisition, and some compromise driven by the survey goals and priorities may be required.

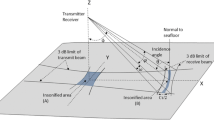

Specific survey design

Dedicated backscatter data acquisition also implies specific survey design. Of particular importance is the system calibration, and hence the allocation of ship time devoted to it. While the swath coverage strategy is similar to a topography survey, i.e. drawing a network of parallel tracks with a few cross-lines, one main difference lies in the amount of coverage overlap controlled by the line spacing (Fig. 4). The backscatter data quality being lower at both ends of the swath and in its central part (due to specular echoes), line spacing must be setup to favour the intermediate angular range. A locally homogeneous quality of backscatter data can be obtained only if the specular sector is replaced by oblique insonification from overlapping swaths. Ideally, coverage should be limited to insonification angles between about 20° and 60° (Fonseca and Mayer 2007; Lamarche et al. 2011), hence substantially decreasing the survey efficiency with regards to bathymetry data (ranging from 0° to 75°). Some coverage redundancy provides the added advantage of insonifying each point on the seafloor from several incidence angles, which has strong potential in term of utilising this property of the backscatter signal for substrate characterisation (Augustin and Lamarche 2015; Lamarche and Augustin in prep).

In the case of repeated surveys over the same area, acquisition conditions should be as similar as possible (e.g., heading directions, survey line patterns, and sonar settings), in order to minimize the artificial variations of the sensor between the successive surveys. Attention should be given to understanding and controlling the impact of the signal absorption in the water column upon the echo intensity measurements. The weather conditions must be monitored carefully, since their impact on the backscatter data usually becomes significant before noticeably impacting the bathymetry data quality. All these constraints, specific to backscatter acquisition, potentially increase the survey duration and costs.

Processing and interpretation

Despite considerable efforts and improvements brought by software developers, backscatter data processing still remains a complex task, involving a number of specialized operations requiring time and effort from experienced operators (Augustin and Lurton 2005; Hellequin et al. 2003; Le Gonidec et al. 2003; Parnum and; Gravilov 2011; Schimel et al. 2015). Our recommendations cover three aspects: software usage, standard processing sequences, and concomitant ground-truthing.

Software usage

We strongly recommend that backscatter users choose one of the few software suites available today and have their operators properly trained to use it, rather than trying to develop new tools in house. Of course this implies that the available software suites provide the functionalities at the expected levels of accuracy, reliability and transparency. We also recommend that, akin to hardware evolutions and sonar settings, satisfactory software configurations are kept in use as long as possible, minimizing the impact of intermediate releases; this is especially important for those users concerned with long-term monitoring of seafloor characteristics.

Standard processing sequences

A same simple post-processing sequence applied to the same backscatter data using different software suites can, in some cases, provide significantly different results (Lucieer et al. 2017). This situation is of course far from optimal for quantitative science. The BSWG has recommended the definition of standardized post-processing sequences, at least for the initial stages, namely data reading and decoding, gain compensations, and normalization (Schimel et al. 2015). To check the consistency of the processing results provided by various software suites, initiatives promoting comparative tests on common data sets should be encouraged, in a similar fashion as for instance the “Shallow Survey” initiative developed for MBES bathymetry datasets (Shallow Survey 2015).

Concomitant ground-truthing

Today’s models of seafloor acoustic backscatter (Jackson and Richardson 2007) are able to explain the main physical phenomena for plain sediments and to predict the orders of magnitude of the backscatter intensity. However, realistic configurations (i.e. involving coarse material, rocks, shells, vegetation, gas bubbles, or biological activity) are still insufficiently covered by these theoretical models. While direct modelling provides valuable tools for understanding and describing the various backscatter phenomena, it remains that no model today is able to give, from an inversion process of backscatter level vs angle and frequency, a set of geological or biological parameters satisfying the expectations of geoscientists or biologists at an accuracy level comparable to the one reached by direct observation, measurement and sampling. Our recommendation is to complement recorded backscatter measurements by ground-truthing as often as possible, and to build data catalogues connecting the acoustical data (as a function of angle and frequency) with the in situ observation and sampling operations, and made widely available. It is of prime importance that backscatter data users, whatever their discipline, be aware of the data limitations and uncertainties, and be careful not to over-interpret the data.

System design and documentation

We provide four categories of recommendations regarding the improvement of current seafloor-mapping sonar functionalities:

Design and implementation of dedicated backscatter calibration and measurement tools

The BSWG report and many recent publications (Gueriot et al. 2000; Heaton 2014; Ladroit et al. 2017; Lurton et al. 2017) have clearly and emphatically shown the importance of calibrating backscatter sonar sensors. Built-in functionalities should make possible the self-calibration (or at least the quality control) of individual modular elements (e.g., transducers, power amplification, receiver input and filters). A number of these functionalities already exist in some systems, e.g., within BIST toolboxes. It is the manufacturer’s role to design the best solutions, the purpose being to provide sonar operators with simple and reliable tools that are able to swiftly provide a complete check-up of the sonar system in terms of backscatter measurement. The results of the various calibration operations should then be accounted for in the settings of the sonar, to make it “self-calibrated” as optimally as possible. When an overall field calibration is possible (e.g. over a well-known reference area, or by cross-comparison with another calibrated system), the operator should be able to input the calibration results inside the system working parameters, so that the real-time results of the survey come from a calibrated sensor. All the sensitivity compensation operations should be reliably recorded when applied.

Reduction of the hardware-driven uncertainties in backscatter measurements

It is also the manufacturer’s responsibility to constrain uncertainties affecting the backscatter measurements at the source. These include Tx and Rx transducer sensitivity; response of electronic modules such as power amplification and reception gain; delivered power; transmitted pulse lengths; and directional patterns of the beam. Although some of these sources of uncertainty can be compensated for at post-processing thanks to calibration processes, it is desirable that their impact be as low as possible. In this respect, more investigation is still needed on various issues, especially regarding the control applicable by users to ensure that all the processing operations are correctly compensated for inside the system, and properly documented.

Improvement of documentation provided to users

For each model of sonar, detailed nominal characteristics (averaged, where realistic) implied in the backscatter measurement should be made available, since this knowledge is paramount throughout the acquisition and processing stages (Schimel et al. 2015). This generic information should be completed by the system’s individual data recorded during the acceptance operations. Moreover, documentation about system calibration operations should be incorporated inside User’s Guides and Operator’s Manuals, regarding the checking of individual modules as well as the overall calibration of the system.

Regarding data processing, software developers should deliver a detailed documentation of the operations applied by their products, thus avoiding dealing with “black-box” processing (Lucieer et al. 2017). Feedback from software companies to sonar manufacturers, and vice-versa, would help improve the data processing applied inside the sonar systems; user communities would benefit from such exchanges between hardware and software manufacturers.

Evolutions toward backscatter-specialized sonars

Most seafloor-mapping sonars propose automated, adapted “modes” of acquisition aimed at optimizing the systems setting according to local conditions to maximize the quality of the bathymetry data and ease the tasks of surveyors. Regarding today’s expectations towards backscatter data acquisition, new modes could be proposed with setting aimed at maximizing the quality and consistency of the backscatter data by minimizing the number of frequency-dependent sectors, thus favouring a smooth angular response and longer pulse durations and avoiding frequency-modulated pulses. For current systems based on a modular architecture of all-digital signal processing, such new functionalities should not need dramatic structural changes in the MBES systems available today.

In the longer term, new seafloor-mapping sonar systems could be optimized for backscatter measurements based on simpler structures than current hydrography MBES, and working on swath extents limited to the intermediate angle sectors. Hydrographic standards outside of ‘safety of navigation’ depths are not so constraining today considering the state-of-the-art capabilities of MBES technology, so that a move to prioritise backscatter data quality over bathymetry could acceptable, even if it means bathymetry would be slightly worse quality but still fit for purpose for the majority of applications. New systems should minimize the number and complexity of transmit sectors and swaths (prone to introduce biases in frequency and angle responses), and favour the reliability of the intensity measurement instead of the extreme spatial resolution and accuracy desirable for hydrographic bathymetry. The sonar industry could benefit in proposing more simple, robust and stable systems for backscatter acquisition for applications such as habitat mapping and environment monitoring. Such systems may not need the technological refinements available today for hydrography, and would satisfy a range of customers expressing specific needs pertinent to backscatter data.

Future requirements

This paper and the work of the BSWG have brought to light a number of remaining unresolved issues pertinent to the measurement, processing and application of seafloor reflectivity. The first category is related to technology issues such as data acquisition and processing, thus associated with development and improvement of hardware, software, acquisition and post-processing procedures and methodologies. A second category of issue relate to applications and end-user’s ultimate expectations, and are associated with the meaning and the use of the information generated by backscatter-related surveys and studies.

There is indeed a plethora of suggestions that can be made as to how these two overarching categories should be addressed. Building on the experience of the BSWG, we provide some ideas below to initiate such a list.

Extension to other sonar systems

Practically, the only systems considered in the BSWG guidelines and recommendations were swath bathymetry sonars, primarily designed for measuring sounding points at oblique angles over a wide stripe of seafloor, and prevalent today in seafloor-mapping operations. The majority of these are MBES; however a number of Phase Measuring Bathymetry Systems (PMBS), based on a similar design and addressing the same challenges for backscatter (Gutierrez et al. 2015), can be included in the same category. The BSWG did not consider other sonar systems of interest in seafloor surveys, such as side-scan sonars (usually unable to provide bathymetry measurements), single-beam echosounders (only receiving vertical echoes) and sub-bottom profilers (designed for sub-seafloor imaging). This could change: the use of SBES as calibrated reference for MBES calibration proves today to be a very reliable and practical solution (Ladroit et al. 2017; Lurton et al. 2017), while the use of high-resolution sub-bottoms seismic profilers can be of high interest for the investigation of the surficial seafloor layers (Hillman et al. 2017; Schneider von Deimling et al. 2016) and interpretation of its backscatter.

Moreover only seafloor-mapping operations were considered, excluding all applications to the imaging and measurement of targets present inside the water column, as justified previously. However, due to the increasing importance of this family of applications for several scientific communities, and since the same MBES systems are increasingly used both for seafloor and water-column applications, this restriction should be removed in future assessments.

Improvements in modelling, instrumentation and processing

Further dedicated studies on backscatter theory and measurement will and should continue, and will undoubtedly require both modeling and ground-truthing approaches. Of note during the BSWG assessment were the issues of footprint modeling and accuracy, i.e. the geometrical description of the insonification, and the impact of water-column absorption upon the recorded signal levels (Schimel et al. 2015; Weber and Lurton 2015). While the issue of absorption by seawater (a canonical topic in underwater acoustics) has for decades generated a significant literature of its own (Ainslie and McColm 1998; Francois and Garrison 1982), much remains to be done regarding the accidental causes of absorption (mainly air bubbles caused by weather conditions and/or platform hydrodynamics, but also turbidity from biological or sedimentary origins) which may significantly influence the results of operations at sea.

Arguably, one of the most often raised issues has been the need for instrumental calibration. Whilst Brown et al. (2015) and Rice et al. (2015) discuss appropriate strategies on calibration, there is most likely a need to improve the formal definition of calibration procedures under their various forms, with emphasis on both cross-calibration methods and definition and use of natural reference areas fulfilling appropriate criteria.

Could these herein recommendations lead toward the development of new sonar systems specialized in seafloor backscatter measurement? The BSWG emphasized that optimization of MBES may be different for bathymetry and for reflectivity measurement purposes. So it is legitimate to wonder if MBES could be designed specifically for backscatter data acquisition and applications.

In the first place, future MBES designed for backscatter strength should be structured more simply. The multiplication of transmitting sectors with individual directivity patterns and pulse frequencies proves to be counterproductive (regarding backscatter applications) because of the resulting increase of complexity which is never perfectly compensated for in post-processing. Also the quality of backscatter measurements implies that the system settings should be kept as stable as possible along a survey, which is in conflict with the very concept of automated modes designed for an optimized adaption to bathymetry measurements but intrinsically resulting in short-term changes in the sonar settings.

With current sonar systems based on a bathymetry-orientated structure, specific backscatter functionalities could be proposed, leading to a limited amount of hardware modifications. More radically, it could be envisioned following what is done in space-borne scatterometer radar (Elachi 1988), and design specific sonar systems aimed at reflectivity, at the detriment of the spatial resolution for an averaged and reliable measure of backscatter. Some drastic structural simplifications (a single transmitting sector, with simplified directivity patterns and signal design) could be compensated for by innovative functionalities, such as multiple frequencies significantly different (typical spaced by one octave) and operated simultaneously, or swaths steerable at several azimuth angles. The latter functionality (aimed at estimating the polarization direction of an organized interface roughness such as sand ripples) is well-known in satellite-borne scatterometers, mainly for applications to the wind direction measurement from azimuth dependence of the sea-surface backscatter. Finally these new sonar systems should incorporate specific and practical functionalities for calibration as discussed above.

Dissemination of concepts and results

The use and uptake of backscatter-related products by applied research or engineering sectors still remains very limited. The capability to acquire backscatter simultaneously with bathymetry data during MBES operations or the potential value of the data is usually known by operators and users but more rarely by managers and planners, let alone knowledge of the benefits that such data could provide to any marine business. One of the reasons for undertaking the BSWG project was in part to promote the use of backscatter by improving the knowledge of the methods and tools related to backscatter data, and providing information on the potential benefits that backscatter-focused research could provide to environmental, exploration, engineering, and hydrographic work.

The constitution of the BSWG provides one relative measure of the community’s interest on backscatter (Lucieer et al. 2017). The dominant sector with an interest in this topic comes from the public sector, with 66% of the members of the BSWG affiliated to Government organizations or universities. The industry sector is represented by software developers and system manufacturers (11% each), while survey companies represent only 11%. This illustrates the fact that backscatter techniques and applications are still considered today (and possibly for good reasons) as an R&D domain rather than a field of routine activity.

We can see several ways of publicizing the use of backscatter imagery in the community, besides encouraging fundamental and applied research projects either on the backscatter data itself or on the derivative products it provides or helps to produce (e.g., geological maps):

-

There is clearly a need for increasing the dissemination and exchange of data resulting from well-controlled acquisition surveys, thus fulfilling the methodological requirements proposed in the BSWG document (Lurton and Lamarche 2015), including the need to apply systematic and proper ground-truthing protocols.

-

Such exchanges could be better structured under the shape of a reference data library or atlas that would be widely accessible and conveniently updatable, including a series of typical or unique acoustic facies. The data, recorded under well-controlled conditions, should be fully documented by metadata, including the acquisition conditions and procedures, the applied processing steps, the ground-truthing results, and a limited amount of interpretative comments. Similar libraries exist for side-scan sonar (Belderson et al. 1972) and seismic reflection data (Bally 1983), where the aim is to facilitate quantitative interpretation of quantitative imagery.

-

The development of a nomenclature of backscatter processing levels provides a means to accurately and efficiently describe the processing status of any backscatter data, and to facilitate better comparison of final processed products from various origins. A normalized metadata format featuring the processed levels of backscatter, and designed to accompany the data at all level of the acquisition-processing-modeling sequence, would need to be formally defined and validated by a group of people larger than the BSWG authors. A preliminary suggestion for such a nomenclature is proposed here in Table 2 (from Lurton et al. 2015).

-

The need for standardization of operations has been identified as a high priority in the results of the analysis of users’ expectations. The purpose is to homogenize as far as possible a number of basic operations (in calibration, acquisition and first-level processing steps), making it possible to directly compare data from various systems, as well as to ensure compatibility between the results obtained by different processing software suites.

Conclusion

The BSWG has completed its initial mandate within a self-imposed duration of two years: the project had to be long enough to address such complex topics at a level of details sufficient to provide useful results. The working load necessary to complete the first report was very significant from a small group of dedicated people and a team of contributors, with no specific budget allocated for the project.

The collaboration of six chapter coordinators, thirteen co-authors, along with two editors and one sub-editor, all with various professional backgrounds and specialties, provided some guarantee of quality and objectivity for the document, which was also reviewed in part or in full by some of the industry partners who contributed to the project. Despite the thoroughness of the process, feedback is still needed and encouraged from all stakeholders. This may warrant the publication of a second edition of the Backscatter Measurements by Seafloor-mapping Sonars. Guidelines and Recommendations (Lurton and Lamarche 2015) in due course.

Beyond the milestone of producing the first issue of the Guidelines and Recommendations, it is highly desirable that a procedure is emplaced for a recurrent updating of the current BSWG report. An obvious reason for this is the constant and rapid evolution of the technical characteristics of sonar systems and processing software suites.

Moreover, the BSWG and this paper have limited their attention to issues and challenges related to seafloor backscatter echoes acquisition and processing, from signal transmission to extraction of a referenced backscattering strength. The work did not deal with data processing for specific interpretation, such as habitat mapping. This self-imposed limitation was required to ensure a thorough and complete first report. Possible follow up of the BSWG report have been identified and include two major themes:

-

Backscatter data post-processing: This theme includes segmentation of the reflectivity maps into homogeneous acoustical facies, extraction of relevant descriptors, classification of the responses along seafloor archetypes, and extraction of quantitative characteristics. The BSWG report includes many of the issues underlying this theme, which are also discussed in depth by the GeoHab group.

-

Water-column backscatter data. Modern MBES systems now provide data for the entire water column. This theme has clearly raised a strong interest internationally as demonstrated by the increase in literature on the subject (Schneider von Deimling et al. 2007).

Most importantly, the success of the BSWG project and its outcomes will be judged in the long term by the uptake and application of the Guidelines and Recommendations by stakeholders, including scientists, and noticeable improvement of the protocols, methodologies and overall consistency in the use of the seafloor backscatter data. This will take time, and will require the members of the BSWG first and foremost to endorse the recommendations and implement them.

This paper provided a summary of the main results and perspectives of the BSWG project. It is also a pertinent and natural introduction to this special issue of Marine Geophysical Research on Seafloor backscatter from swath echosounders: technology and applications, whose purpose is to present a number of recent results and advances in the field of seafloor backscatter measurement and processing. Some papers in this issue are directly derived from the BSWG report and present an update on the group’s work. Others present recent research, developed in the wake of the BSWG recommendations, hopefully demonstrating the potentialities of the approach followed by the working group, and possibly opening pathways to new ideas.

References

Ainslie MA, McColm JG (1998) A simplified formula for viscous and chemical absorption in sea water. J Acoust Soc Am 103:1671. doi:10.1121/1.421258

Anderson JT, Van Holliday D, Kloser R, Reid DG, Simard Y (2008) Acoustic seabed classification: current practice and future directions. ICES J Mar Sci 65:1004–1011. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsn061

ASAR (1998) SP-1225: ASAR science and applications. European Spatial Agency (ESA) Publication, Noordwijk

Augustin J-M, Lamarche G (2015) High-redundancy multibeam echosounder backscatter coverage over strong relief. In: Underwater Acoustics Group (ed) Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics, Seabed and Sediment Acoustics: measurements and modelling conference, University of Bath, UK, 7–9 September 2015, vol 37(pt.1), pp 93–101

Augustin JM, Lurton X (2005) Image amplitude calibration and processing for seafloor mapping sonars. In: Oceans 2005: Europe, 20–23 June 2005, vol 1, pp 698–701. doi:10.1109/OCEANSE.2005.1511799

Augustin JM, Le Suave R, Lurton X, Voisset M, Dugelay S, Satra C (1996) Contribution of the multibeam acoustic imagery to the exploration of the sea-bottom: examples of SOPACMAPS 3 and ZoNéCo 1 cruises. Mar Geophys Res 18:459–486

Bally AW (1983) Seismic expression of structural styles: a picture and work atlas, vol 3. AAPG studies in geology series #1. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Tulsa

Belderson RH, Kenyon NH, Stride AH, Stubbs AR (1972) Sonographs of the sea floor. A picture atlas. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Blondel P, Murton BJ (2000) Handbook of seafloor sonar imagery. Wiley, Chichester, p 314

Bourillet J-F, Edy C, Rambert F, Satra C, Loubrieu B (1996) Swath mapping system processing: bathymetry and cartography. Mar Geophys Res 18:487–506

Brown CJ, Blondel P (2009) Developments in the application of multibeam sonar backscatter for seafloor habitat mapping. Appl Acoust 70:1242–1247. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2008.08.004

Brown RJ, Brisco B, Ahern FJ, Bjerkelund C, Manore M, Pultz TJ, Singhroy V (1993) SAR application calibration requirements. Can J Remote Sens 19:193–203. doi:10.1080/07038992.1993.10874549

Brown CJ, Todd BJ, Kostylev VE, Pickrill RA (2011a) Image-based classification of multibeam sonar backscatter data for objective surficial sediment mapping of George Bank, Canada. Cont Shelf Res 31:S110–S119. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2010.02.009

Brown CJ, Smith SJ, Lawton P, Anderson JT (2011b) Benthic habitat mapping: a review of progress towards improved understanding of the spatial ecology of the seafloor using acoustic techniques. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 92:502–520. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2011.02.007

Brown CJ, Samento JA, Smith SJ (2012) Multiple methods, maps, and management applications: purpose made seafloor maps in support of ocean management. J Sea Res 72:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2012.04.009

Brown C, Schmidt V, Malik M, Le Bouffant N (2015) Chap. 4: Backscatter measurement by bathymetric echo sounders. In: Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars—guidelines and recommendations. Geohab Report, pp 79–106. http://geohab.org/publications/

Calder B (2003) Automatic statistical processing of multibeam echosounder data. Int Hydrog Rev 4:53–68

Chen HS (1984) Space remote sensing systems: an introduction. Academic Press, Orlando

Clarke JEH, Mayer LA, Wells DE (1996) Shallow-water imaging multibeam sonars: a new tool for investigating seafloor processes in the coastal zone and on the continental shelf. Mar Geophys Res 18:607–629

Clarke JEH, Danforth BW, Valentine P (1997) Areal seabed classification using backscatter angular response at 95 kHz. Paper presented at the high frequency acoustics in shallow water, NATO SACLANT Undersea Research Centre, Lerici, Italy, 30 June to 4 July 1997

Cochrane GR, Lafferty KD (2002) Use of acoustic classification of sidescan sonar data for mapping benthic habitat in the Northern Channel Islands, California. Cont Shelf Res 22:683–690

Collot J-Y, Delteil J, Lewis KB et al (1996) From oblique subduction to intra-continental transpression: structures of the southern Kermadec-Hikurangi margin from multibeam bathymetry, side scan sonar and seismic reflection. MGR 18:357–381. doi:10.1007/BF00286085

Dartnell P, Gardner JV (2004) Predicting seafloor facies from multibeam bathymetry and backscatter data. Photogram Eng Remote Sens 70:1081–1091

de Moustier C (1986) Beyond bathymetry: mapping acoustic backscattering from the deep seafloor with Sea Beam. J Acoust Soc Am 79:316–331

De Moustier C, Matsumoto H (1993) Seafloor acoustic remote sensing with multibeam echo-sounders and bathymetric sidescan sonar systems. Mar Geophys Res 15:27–42

Demer DA, Berger L, Bernasconi M et al (2015) Calibrations of acoustic instruments. ICES Cooperative Research Report, Copenhagen

Dugelay S, Graffigne C, Augustin JM (1996) Deep seafloor characterization with multibeam echosounders by image segmentation using angular acoustic variations. Paper presented at the SPIE 2823, statistical and stochastic methods for image processing, Denver, CO, 8 October 1996, vol 2884, pp 255–266

Durand S, Legendre P, Juniper SK (2006) Sonar backscatter differentiation of dominant macrohabitat types in a hydrothermal vent field. Ecol Appl 16:1421–1435

Elachi C (1988) Spaceborne radar remote sensing: applications and techniques. IEEE Press, New York

Fonseca L, Calder B (2006) Geocoder: an efficient backscatter map constructor. Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, Durham

Fonseca L, Mayer L (2007) Remote estimation of surficial seafloor properties through the application of angular range analysis to multibeam sonar data. Mar Geophys Res 28:119–126

Foote KG, Knudsen HP, Vestnes G, MacLennan DN, Simmonds EJ (1987) Calibration of acoustic instruments for fish density estimation: a practical guide. Cooperative research report, international council for the exploration of the sea, Copenhagen

Foote KG, Chun D, Hammar TR, Baldwin KC, Mayer LA, Hufnagle LC, Jech JM (2005) Protocols for calibrating multibeam sonar. J Acoust Soc Am 117:2013–2027. doi:10.1121/1.1869073

Francois RE, Garrison GR (1982) Sound absorption based on ocean measurements: part II: boric acid contribution and equation for total absorption. J Acoust Soc Am 72:1879–1890

Freeman A (1992) SAR calibration: an overview. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote 30(6):1107–1121

Gueriot D, Chedru J, Daniel S, Maillard E (2000) The patch test: a comprehensive calibration tool for multibeam echosounders. In: MTS/IEEE oceans conference and exhibition on where marine science and technology meet, vol 3, pp 1655–1661. doi:10.1109/OCEANS.2000.882178

Guillon L, Lurton X (2001) Backscattering from buried sediment layers: the equivalent input backscattering strength model. J Acoust Soc Am 109:122–132

Gutierrez F, Manley-Cooke P, Tamset D (2015) Calibrated side scan images from a phase measuring bathymetric sonar. Paper presented at the shallow survey 2015, Plymouth, UK

Haniotis S, Cervenka P, Negreira C, Marchal J (2015) Seafloor segmentation using angular backscatter responses obtained at sea with a forward-looking sonar system. Appl Acoust 89:306–319. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2014.09.025

Hasan RC, Ierodiaconou D, Laurenson L (2012) Combining angular response classification and backscatter imagery segmentation for benthic biological habitat mapping. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 97:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2011.10.004

Hasan RC, Ierodiaconou D, Laurenson L, Schimel A (2014) Integrating multibeam backscatter angular response, mosaic and bathymetry data for benthic habitat mapping. PLoS ONE 9:e97339

Heaton JE (2014) Utilizing an extended target for high frequency multi-beam sonar intensity calibration. M.Sc. Thesis, University of New Hampshire

Hellequin L, Boucher JM, Lurton X (2003) Processing of high-frequency multibeam echo sounder data for seafloor characterization. IEEE J Ocean Eng 28:78–89. doi:10.1109/JOE.2002.808205

Hillman J, Lamarche G, Pallentin A, Pecher I, Gorman A, Schneider von Deimling J (2017) Validation of automated supervised segmentation of multibeam backscatter data from the Chatham Rise, New Zealand. In: Seafloor backscatter data from swath mapping echosounders: from technological development to novel applications, Marine Geophysical Research, 1–23. doi:10.1007/s11001-016-9297-9

Huang Z, Siwabessy J, Nichol S, Anderson T, Brooke B (2013) Predictive mapping of seabed cover types using angular response curves of multibeam backscatter data: testing different feature analysis approaches. Cont Shelf Res 61–62:12–22. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2013.04.024

IHO (2008) IHO standards for hydrographic surveys, 5th edn. International Hydrographic Bureau, Monaco (Special Publication N°44)

Jackson DR, Briggs KB (1992) High-frequency bottom backscattering: roughness versus sediment volume scattering. J Acoust Soc Am 92:962–977

Jackson DR, Richardson M (2007) High frequency seafloor acoustic. Springer, New York

Jackson DR, Ishimaru A, Winebrenner DP (1986) Application of the composite roughness model to high frequency bottom backscattering. J Acoust Soc Am 79:1410–1422

Klaucke I, Masson DG, Petersen CJ, Weinrebe W, Ranero CR (2008) Multifrequency geoacoustic imaging of fluid escape structures offshore Costa Rica: implications for the quantification of seep processes. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 9:Q04010. doi:10.1029/2007GC001708

Kloser RJ, Penrose JD, Butler AJ (2010) Multi-beam backscatter measurements used to infer seabed habitats. Cont Shelf Res 30:1772–1782. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2010.08.004

Ladroit Y, Lamarche G, Pallentin A (2017) Seafloor multibeam backscatter calibration experiment—comparing tilted 38 kHz split-beam echosounder and 30 kHz multibeam data. In: Seafloor backscatter data from swath mapping echosounders: from technological development to novel applications, Marine Geophysical Research (this issue)

Lamarche G, Augustin J-M (in prep) Potential of manifold overlap multibeam swath coverage for seafloor backscatter study. Mar Geophys Res

Lamarche G, Lurton X, Verdier A-L, Augustin J-M (2011) Quantitative characterization of seafloor substrate and bedforms using advanced processing of multibeam backscatter. Application to the Cook Strait, New Zealand. Cont Shelf Res 31:S93–S109. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2010.06.001

Lamarche G, Orpin A, Mitchell J, Pallentin A (2016) Chap. 5: Benthic habitat mapping. In: Clark MR, Consalvey M, Rowden AA (eds) Biological sampling in the deep sea. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, pp 80–102

Laughton AS (1981) The first decade of Gloria. J Geophys Res 86:11511–11534. doi:10.1029/JB086iB12p11511

Le Chenadec G, Boucher JM, Lurton X (2007) Angular dependence of K-distributed sonar data. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote 45:1224–1235. doi:10.1109/TGRS.2006.888454

Le Gonidec Y, Lamarche G, Wright IC (2003) Inhomogeneous substrate analysis using EM300 backscatter imagery. MGR 24:311–327. doi:10.1007/s11001-004-1945-9

Lucieer V, Lamarche G (2011) Unsupervised fuzzy classification and object-based image analysis of multibeam data to map deep water substrates, CookStrait, New Zealand. Cont Shelf Res 31:1236–1247. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2011.04.016

Lucieer VL, Roche M, Degrendele K, Malik M, Dolan M (2015) Chap. 3: Seafloor backscatter user needs and expectations. In: Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars—guidelines and recommendations. Geohab Report, pp 53–78. http://geohab.org/publications/

Lucieer V, Roche M, Degrendele K, Malik M, Dolan M, Lamarche G (2017) User expectations for multibeam backscatter data—looking back into the future. In: Seafloor backscatter data from swath mapping echosounders: From technological development to novel applications, Marine Geophysical Research (This issue)

Lurton X (2010) An introduction to underwater acoustics. Principles and applications. 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) (2015) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars. Guidelines and recommendations vol Geohab Report. http://geohab.org/publications/

Lurton X, Augustin JM, Dugelay S, Hellequin L, Voisset M (1997) Shallow-water seafloor characterization for high-frequency multibeam echosounder: image segmentation using angular backscatter. In High frequency shallow water acoustics (Pace ed.), SACLANTCEN conference proceedings CP-45

Lurton X, Lamarche G, Brown CJ, Heffron E, Lucieer VL, Rice G, Schimel A, Weber T (2015) Seafloor backscatter acquisition and processing: best practice and recommendations by the GeoHab backscatter working group, In: Bath UO (ed) Proceedings of the Institute of acoustics, seabed and sediment acoustics: measurements and modelling conference, University of Bath, UK, pp. 242–249

Lurton X, Eleftherakis D, Augustin J-M (2017) Analysis of seafloor backscatter strength dependence on the azimuthal angle using multibeam echosounder data. In: Seafloor backscatter data from swath mapping echosounders: from technological development to novel applications, Marine Geophysical Research (this issue)

Luscombe AP, Thompson A (2011) RADARSAT-2 calibration: proposed targets and techniques. Paper presented at the geoscience and remote sensing symposium. IGARSS ‘01. IEEE 2001 International Sydney, NSW, vol 1, pp 496–498

Mayer LA (2006) Frontiers in seafloor mapping and visualization. Mar Geophys Res 27:7–17. doi:10.1007/s11001-005-0267-x

McGonigle C, Collier JS (2014) Interlinking backscatter, grain size and benthic community structure. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 147:123–136. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2014.05.025

McGonigle C, Grabowski JH, Brown CJ, Weber TC, Quinn R (2011) Detection of deep water benthic macroalgae using image-based classification techniques on multibeam backscatter at Cashes Ledge, Gulf of Maine, USA. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 91:87–101. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2010.10.016

McRea JE Jr, Greene HG, O’Connell VM, Wakefield WW (1999) Mapping marine habitats with high resolution sidescan sonar. Oceanol Acta 22:679–686

Medialdea T, Somoza L, León R et al (2008) Multibeam backscatter as a tool for sea-floor characterization and identification of oil spills in the Galicia Bank. Mar Geol 249:93–107. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2007.09.007

NOAA (2014) Field procedures manual, national oceanic and atmospheric administration, office of coast survey. http://www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/hsd/fpm/2014_FPM_Final.pdf

Novarini JC, Caruthers JW (1998) A simplified approach to backscattering from a rough seafloor with sediment inhomogeneities. IEEE J Ocean Eng 23:157–166

Parnum IN, Gravilov AN (2011) High-frequency multibeam echo-sounder measurements of seafloor backscatter in shallow water: part 1—data acquisition and processing. Int J Soc Underw Technol 30:3–12. doi:10.3723/ut.30.003

Pratson LF, Edwards MH (1996) Introduction to advances in seafloor mapping using sidescan sonar and multibeam bathymetry data. Mar Geophys Res 18:601–605

Preston JM, Christney AC, Bloomer SF, Beaudet IL (2001) Seabed classification of multibeam sonar images. In: Oceans conference record (IEEE) 4(MTS 0-933957-28-9), pp 2616–2623

Renard R, Allenou J-P (1979) Sea beam, multibeam echosounding in “Jean Charcot” description, evaluation and first results. Int Hydrog Rev LVI:35–67

Rice G, Cooper R, Degrendele K, Gutierrez F, Le Bouffant N, Roche M (2015) Chap. 5: Acquisition: best practice guide. In: Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars—guidelines and recommendations. Geohab report, pp 79–132. http://geohab.org/publications/

Rzhanov Y, Fonseca L, Mayer L (2012) Construction of seafloor thematic maps from multibeam acoustic backscatter angular response data. Comput Geosci 41:181–187. doi:10.1016/j.cageo.2011.09.001

Schimel A, Beaudoin J, Gaillot A, Keith G, Le Bas T, Parnum I, Schmidt V (2015) Chap. 6: Processing backscatter data: from datagrams to angular responses and mosaics. In: Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars—guidelines and recommendations. Geohab report, pp 133–164. http://geohab.org/publications/

Schneider von Deimling J, Brockhoff J, Greinert J (2007) Flare imaging with multibeam systems: data processing for bubble detection at seeps. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 8:Q06004. doi:10.1029/2007GC001577

Schneider von Deimling J, Held P, Feldens P, Wilken D (2016) Effects of using inclined parametric echosounding on sub-bottom acoustic imaging and advances in buried object detection. Geo Mar Lett 36:113–119. doi:10.1007/s00367-015-0433-3

Shallow Survey (2015) Common dataset. http://www.shallowsurvey2015.org/?page=commondataset.

Simrad (1992) Simrad EM12 hydrographic echo sounder, product description: Simrad subsea A/S, Horten, Norway, #P2302E.

Weber T, Lurton X (2015) Chap. 2: Background and fundamentals. In: Lurton X, Lamarche G (eds) Backscatter measurements by seafloor-mapping sonars—guidelines and recommendations. Geohab report, pp 25–52. http://geohab.org/publications/

Acknowledgements

We firstly and wholeheartedly thank the authors of the Backscatter Working Group's Guidelines and Recommendations report: Tom Weber, Glen Rice and Erin Heffron (University of New Hampshire), Vanessa Lucieer (University of Tasmania), Craig Brown (Nova Scotia Community College), and Alexandre Schimel (now NIWA). We also thank all the members of the BSWG for their support during the development of the report, and Vanessa Lucieer (IMAS-University of Tasmania) for proofreading the last version of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIWA programme Marine Physical Processes and Resources (COPR1703) and Ifremer R&D project in Underwater Acoustics (PJ0807).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamarche, G., Lurton, X. Recommendations for improved and coherent acquisition and processing of backscatter data from seafloor-mapping sonars. Mar Geophys Res 39, 5–22 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-017-9315-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-017-9315-6