Abstract

There are few data on the educational needs of children with cri-du-chat syndrome: a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects learning and development. We therefore designed an Internet survey to identify parents’ educational priorities in relation to children’s level of need/ability. The survey listed 54 skills/behaviors (e.g., toileting, expresses wants and needs, and tantrums) representing 10 adaptive behavior domains (e.g., self-care, communication, and problem behavior). Parents rated their child’s current level of ability/performance with respect to each skill/behavior and indicated the extent to which training/treatment was a priority. Fifty-four surveys were completed during the 3-month data collection period. Parents identified nine high priority skills/behaviors. Results supported the view that parent priorities are often based on the child’s deficits and emergent skills, rather than on child strengths. Implications for educational practice include the need for competence to develop high priority skills/behaviors and the value of assessing children’s deficits and emergent skills to inform the content of individualized education plans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cri-du-chat syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder arising from anomalies of chromosome 5 (Niebuhr 1978). The syndrome was first identified in 1963 by a team of French researchers (Lejeune et al. 1963). Specifically, Lejeune et al. described three children with a triad of characteristics that appeared to constitute a new and unique syndrome. Perhaps the most striking characteristic, and the one that gave the syndrome its name, was the distinctive cat-like sound of the children’s cry (Sigafoos et al. 2009). This sound has been described as “a distinct high-pitched monochromatic cry at birth,” which is “similar to the mewing of a cat” (Ohr 1998, p. 192). The second characteristic of cri-du-chat syndrome is a significant degree of mental retardation. While many children with cri-du-chat present with significant intellectual disability, recent evidence suggests that the IQ scores of these children can vary from being profoundly impaired to functioning in the normal range of intellectual ability (Cornish and Bramble 2002). Physical anomalies, including microcephaly, increased width between the eyes, and a rounded moonlike face, constitute a third set of characteristics associated with cri-du-chat syndrome (Ohr 1998).

Cri-du-chat syndrome is relatively rare, with prevalence estimated at 1 in every 37,000 live births (Higurashi et al. 1990). Perhaps because of its relatively low prevalence, cri-du-chat syndrome has received relatively little attention from special education researchers and professionals. Still, as Ohr (1998) noted, the prevalence of cri-du-chat among people with mental retardation may be as high as 1 in every 350 individuals. Thus, it would not be uncommon for special education professionals to encounter children with cri-du-chat syndrome during their career. Consequently, it would seem important for special education professionals to have some understanding of the developmental and behavioral characteristics of these children.

Descriptive accounts of the developmental and behavioral characteristics associated with cri-du-chat syndrome have identified significant deficits in these children’s learning abilities, language development, academic achievement, and overall adaptive behavior functioning (Cornish and Bramble 2002; Ohr 1998). Many children with cri-du-chat syndrome also present with severe behavior problems, such as self-injury, aggressive behavior, and stereotyped movement disorder (Cornish and Bramble 2002). Evidence suggests that many of these developmental and behavioral problems can be linked to specific genotypes; that is, they may represent behavioral phenotypes of the syndrome. Consequently, the extent to which these behavioral phenotypes can be modified by behavioral and educational intervention is of considerable applied importance when designing an appropriate educational curriculum.

Given developmental and behavioral characteristics associated with cri-du-chat syndrome it is highly likely that most of these children will require special education. In many countries, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States of America, an individualized education plan (IEP) forms the basis for provision of special education to children with developmental and physical disabilities (Snell and Brown 2006). An IEP will typically delineate the priority educational goals for the child and the procedures that will be implemented in an attempt to achieve those goals. Current best practice dictates that the child’s IEP should be developed through a collaborative approach between parents and professionals (Orelove and Sobsey 2004). Indeed, there appears to be a general consensus that IEP goals should reflect parent priorities for the child’s learning and development. It would therefore seem critical for professionals to identify the educational priorities that parents have for their children. With respect to cri-du-chat syndrome, there appear to be no systematic investigations into the types of educational goals that are likely to be priorities for the parents of these children.

The initial aim of this study was to identify the educational priorities that parents had for their children with cri-du-chat syndrome. Information of this type may enable professionals to more effectively target educational assessments to high priority areas, which might, in turn, facilitate development of appropriate curriculum and interventions. A second aim of the study was to determine whether parent identified priorities reflected the child’s skill deficits or areas of relative strength. This aim was considered important given current debate within the special education literature regarding the value of ameliorating the child’s skill deficits versus working to enhance existing areas of strength (Seale and Nind 2009; Valencia 1997). While ameliorating deficits and enhancing strengths are not necessarily mutually exclusive, the extent to which parents are likely to prioritize deficits versus strengths would seem to have some bearing on efforts to identify and accommodate parent priorities within the child’s IEP.

Method

Survey Development, Content, and Instructions

We developed a surveyFootnote 1 to identify parents’ educational priorities in relation to the child’s level of ability/performance across a number adaptive skills and specific problem behaviors. The survey included an initial page of background information (e.g., purpose of the survey, statement on informed consent, and estimated completion time) and instructions for completing the survey. Following this, the survey had three sequential sections: Parts A, B, and C.

Part A asked parents to provide information about their child. Specific details sought were: (a) gender, (b) age, (c) where the child lived (e.g., at home with parents, in a community group home), (d) where the child attended school (e.g., public versus private school), (e) primary diagnosis, (f) level of intellectual ability in terms of IQ scores, (g) level of speech/communication development (i.e., age-appropriate/fluent speech to does not speak), and (h) presence of any additional impairments (e.g., hearing or vision impairment).

Part B asked parents to provide information about themselves. Specific details sought were: (a) their relation to the child (mother, father), (b) age, (c) knowledge of their child’s disability (i.e., very extensive to very limited), (d) knowledge of their child’s educational program (i.e., very extensive to very limited), (e) country where they lived, (f) ethnic or cultural background, and (g) level of formal education.

Part C provided a list of 44 adaptive skills (e.g., toileting, expressing wants and needs, and preparing simple meals) and 10 specific problem behaviors (e.g., tantrums, self-injury, and hyperactivity). These 54 skills/behaviors were derived from three sources: (a) a review of several functional curricula for children with developmental disabilities (Lovaas 2003; Orelove and Sobsey 2004; Snell and Brown 2006; Vaughn et al. 2007), (b) a review of the adaptive behavior construct and commonly used measures of adaptive behavior functioning (Carr and O’Reilly 2007), and (c) the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Checklist (ICF Checklist) (World Health Organization 2003).

Part C was sub-divided into 10 domains based on the categories included in the ICF Checklist. The specific domains included in Part C were as follows: (a) self-care skills, (b) domestic living skills, (c) community living skills, (d) job skills, (e) recreational skills, (f) motor skills, (g) social skills, (h) communication skills, (i) academic skills, and (j) problem behavior. Under each of these 10 domains, from 3 to 10 more specific skills/behaviors were listed. Under the self-care domain, for example, six more specific skills were listed including: (a) washing oneself, (b) toileting, and (c) feeding. Similarly, under the social skills domain, six more specific skills were listed, including: (a) shows affection to caregivers, (b) seeks out interaction with others, and (c) makes friends.

For each skill/behavior listed in the survey parents were asked to rate their child’s current level of ability/performance with respect to that skill/behavior. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (is independent) to 4 (is totally dependent). A strength would therefore be any skill rated at the more independent end of the scale (e.g., 1 or 0), whereas a deficit was viewed as any skill where the child’s performance was rated at the more dependent end of this scale (e.g., 3 or 4). The wording of this rating scale was modified for the 10 specific behaviors in the problem behavior domain. Specifically, respondents were asked to rate the extent to which various specific behaviors (e.g., self-injury, hyperactivity, sleep disturbance) were a problem. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale (0 = not a problem; 4 = major problem). In addition, for each skill/behavior, respondents were asked to rate how important it was for their child to receive education, training, or treatment for that skill/behavior. These ratings were also made on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all a priority) to 4 (very high priority). A final survey item asked parents to indicate whether or not that skill/behavior was currently being addressed in their child’s educational program (yes, no, or don’t know/unsure).

Survey Distribution

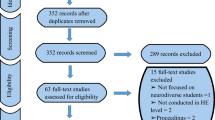

The survey was uploaded to a commercial website (i.e., SurveyMonkey.comTM), which generated an internet link for accessing the survey. A GoogleTM search was conducted to identify associations that provided information and support to parents of children with cri-du-chat syndrome. The free-text search terms for the GoogleTM search included: (a) cri-du-chat syndrome parent organizations, and (b) cri-du-chat syndrome parent support. We then visited the websites for relevant organizations to locate email addresses for the contact person(s) (e.g., the president, secretary, and membership officer). These organizations/individuals were sent an email that included an informational letter describing the survey and a link to the survey on SurveyMonkey.comTM. This email included a request to forward the link and information about the survey to the parents who were affiliated with that organization.

Ethical approval to undertake the study had been received by the appropriate university committee prior to launching the survey. Once the survey was launched, it remained open for a 3-month period (November 2008 to January 2009). At the end of the 3-month period, all surveys in which the child’s primary diagnosis was listed as cri-du-chat syndrome were downloaded for analysis.

Data Analysis

Data were exported into SPSS® for analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated to provide an overview of the demographic characteristics of the parents and their children with cri-du-chat syndrome (e.g., age, gender, geographic location, presence of additional handicapping conditions). Next, the mean priority rating was calculated for each skill listed in the survey to identify the highest priority skills/behaviors. Highest priority skills/behaviors were defined as those that received a mean rating of 3.0 (high priority) or greater on the 0 (not at all a priority) to 4 (very high priority) scale. For each priority skill/behavior, the percentage of children who were said to be receiving training on that skill/behavior as part of their current educational program was calculated.

To allow for a more parsimonious description of relationships, we conducted factor analyses for each of the 10 adaptive behavior domains and then for each corresponding priority rating. It is important to note that we did not conduct a factor analysis using all of the variables in one analysis. Given the small sample size, a factor analysis of this type would not produce meaningful results. Instead, we conducted a factor analysis for the items comprising a single domain, such as a separate factor analysis for job skills, a separate factor analysis for job priorities, and so on. For this analysis, we used principal axis extraction with oblique rotation (delta = 0). Common factor analysis was used because it is an appropriate method when latent variables are presumed to underlie responses to a set of items (Ford et al. 1986). When multiple factors were present for a given domain, which occurred infrequently, an oblique rotation was selected to identify if factors were correlated.

To identify the number of factors to retain in the solution, we initially retained factors that had eigenvalues greater than 1 and examined scree plots. Further, items were retained only if their factor loading (pattern coefficient) exceeded 0.50. We then formed factor scores by computing means across the items that loaded on a given factor. Note that when we computed these means, we retained cases that responded to at least 50% of the items comprising a given factor. The decision to use information from these cases was made to provide for as much statistical power as possible, given the sample size. Further, although our sample size was somewhat small, Stevens (2009, p. 333) noted that factors can be considered reliable regardless of sample size when (a) the four largest loadings average .6 or higher or (b) the three largest loadings have an average that is .8 or higher. Of the 25 factors we created below, 20 met this requirement.

After creating the factors, we then computed correlations between the ratings of ability/performance for each factor and the corresponding priority ratings. This analysis was intended to determine if there was any significant linear relation between children’s level of ability/performance within each specific adaptive behavior domain and the extent to which that domain was considered an educational priority by parents. That is, did the parents prioritize the children’s strengths or deficits?

We also conducted nonlinear (i.e., quadratic) regression analyses for each of the domains and the corresponding priority ratings, with priority rating as the dependent variable. This analysis was done to examine the possibility that parents had higher priorities when their children had mid-range or emerging abilities and lower priority ratings when their children had much higher or much lower abilities. That is, did the parent target emerging skills/behaviors as educational priorities? These final analyses were conducted separately for each of the 10 domains (e.g., self-care, communication, social skills, etc.).

Because there were 10 different adaptive behavior domains, we used an alpha of .01 to test the correlation coefficients for significance and control for the inflation of the family-wise error rate. To test for a curvilinear relationship between the ability/performance and priority ratings, we used an alpha of .05 due to the additional degree of freedom used to test this relationship and the desire to maintain statistical power. To retain as much power as possible, we used all available cases for a given domain in conducting these analyses. Thus, sample sizes, which we provide below, vary somewhat from domain to domain.

Results

Number of Submissions

Fifty-four surveys were submitted during the 3-month data collection period. A review of each submission provided no evidence of multiple submissions or any technical difficulties that would have influenced the results. For each of the 54 completed survey submissions, the child’s primary diagnosis was cri-du-chat syndrome. The results which follow are based on the analysis of these 54 completed surveys.

Characteristics of the Respondents

Relationship of Respondent to Child

Of the 54 submissions, 51 respondents (94%) indicated their relationship to the child. Of these, 46 (90%) were the child’s mother and the remaining 5 (10%) surveys were completed by the child’s father.

Age of Respondents

Of the 54 submissions, 52 (96%) indicated their age by indicating which of nine [5-year] age groupings (e.g., 21–25, 26–30, 31–35, etc) they fell into. Overall, the respondents ranged from 21 to 61+ years of age with 30% in the 36–40 year age range. This was followed by 15.4% in both of the 31–35 and 41-45 age groupings. A further 13.5% of the respondents fell in the 46–50 year age group. The remaining age groups each comprised of less than 8% of the respondents.

Geographic Location, Cultural/Ethnic, and Educational Background of Respondents

When asked to indicate their country of residence, 50 respondents (92%) provided data. Most of these 50 respondents lived in the United States of America (n = 42, 84%). The next largest groups lived in Canada (n = 5, 10%) and Australia (n = 3, 6%). Only 32 respondents indicated their cultural or ethnic background, with the majority of these describing themselves as European or European-American (n = 28, 87%). The four remaining respondents identified themselves as Native American, African-American, Asian, and Hispanic, respectively (i.e., n = 1 each). Fifty-two respondents indicated their level of formal education. Over half of these respondents (n = 31, 60%) indicated that they had completed a university degree, while the remaining had completed some university education (n = 10, 19%), completed a post-secondary qualification (n = 9, 17%), or completed high school (n = 2, 4%).

Knowledge of Child’s Disability and Educational Program

Fifty-two respondents indicated their level of knowledge regarding their child’s disability. Most indicated that their level of knowledge was either extensive (n = 27, 52%) or very extensive (n = 15, 29%), followed by average (n = 9, 17%), or below average (n = 1, 2%). None of these 52 respondents indicated that their knowledge of the child’s disability was limited or very limited. With respect to knowledge of the child’s educational program, 52 parents responded. Most indicated that their level of knowledge was extensive (n = 24, 46%), followed by very extensive (n = 13, 25%) and average (n = 13, 25%). Two parents indicated that their knowledge was below average or very limited.

Characteristics of the Respondents’ Children

Age

The child’s age was indicated on all 54 submissions. The most frequently reported age ranges were: 11 to 13 years (n = 11, 20%), 5 to 7 years (n = 9, 17%), 14 to 16 years (n = 7, 13%), 2 to 4 years (n = 7, 13%), and 8 to 10 years (n = 6, 11%), respectively. There were relatively fewer children under 2 (n = 5, 9%), between 17 to 21 years (n = 5, 9%), or over 21 years of age (n = 4, 7%).

Gender

The gender of the children for whom the surveys were completed was indicated on all 54 submissions. The sample included more girls (n = 35, 65%) than boys (n = 19, 35%).

Types and Severity of Disability

Parents were asked to indicate the types and severity of their child’s disability by indicating the child’s primary diagnosis, additional impairments, level of intellectual disability, and level of speech/communication development. Cri-du-chat was the primary diagnosis for all 54 children. Additional impairments included physical disability (n = 19, 59%), hearing impairment (n = 10, 31%), vision impairment (n = 9, 28%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (n = 6, 19%), and seizure disorder (n = 5, 16%). Level of intellectual disability was indicated for 47 children and most of these children were said to have severe (n = 16, 34%) or moderate (n = 15, 32%) intellectual disability, followed by mild (n = 10, 21%) and profound (n = 3, 6%) intellectual disability. The remaining three children were said to have average to below average IQ. Level of speech/communication development was indicated for 43 children and most of these either did not speak (n = 24, 56%) or spoke only a few single words or simple sentences (n = 18, 42%). The remaining child was reported to have fluent speech. Most of the children lived at home with their parents (n = 51, 94%) and attended public school (n = 33, 67%). Other children attended private school (n = 3, 6%), early intervention or day care centers (n = 6, 12%), or were home-schooled (n = 6, 12%).

High Priority Skills

Table 1 lists the nine skills that were classified as high priority based on having received a mean rating of 3.0 or greater on the 0 (not at all a priority) to 4 (very high priority) scale. The mean priority ratings and the percentage of children receiving training on each skill are also listed. Five of the nine high priority skills represented behaviors from the communication domain (i.e., describe events/feelings, follows directions, responds appropriately to questions, asks for information when needed, and expresses wants and needs). The other four high priority skills were drawn from the community living (i.e., personal safety, pedestrian safety), self-care (i.e., toileting) and academic (i.e., listens to teacher) domains. The percentage of children who were said to be receiving training on high priority skills ranged from 40% (personal safety) to 86.4% (expresses wants and needs). With the exception of the two community living skills (i.e., personal safety, pedestrian safety), the majority of children were said to be receiving training on seven of the nine high priority skills.

Factor Analyses

Prior to conducting the factor analyses, we examined the dataset for missing data. We found that responses to two items had substantial missing data. Specifically, only 21 of 54 cases (39%) responded to the item about the skills their child exhibited in the use of a wheelchair (motor skills domain), and only 32 cases (59%) responded to the item regarding skills in engaging in appropriate intimate relationships (social skills domain). Since these items do not appear to be germane to the sample at hand and, if used, would have substantially reduced the sample size for the factor analyses, we dropped these items from these and all remaining analyses. We also dropped the corresponding items from the respective priority domains. All remaining items were used in the factor analyses.

Table 2 shows the results of the factor analyses. For the 10 domain-based skills/performance ratings and corresponding 10 domain-based priority ratings, the responses to the items for 16 domains were due to a single common factor. For these one-factor domains, all but one item (shows affection to caregivers in the social skills domain) had loadings exceeding the .50 threshold. For domains in which there was evidence supporting the presence of multiple factors, the factors seemed generally interpretable, and they were used in further analyses below. Two factors underlie responses for items on three of the domains. For the self-care priorities domain, examining the items that load on the first factor suggested a bodily-appearance factor, and the items that load on the second factor suggest a bodily-function factor. For the academic skills domain, the items that load on the first factor suggest core academic skills and items that load on the second factor suggest a school-behavior factor. For the problem behavior domain, three factors were present. The first factor comprises severe challenging behavior (e.g., aggression, self-injury), the second factor includes eating and sleeping disturbances, and the third factor includes only a single item, which is lack of activity. Finally, two factors were present for problem behavior priorities. The first reflects challenging behavior, and the second reflects sleep disturbance.

Results of the correlation and polynomial regression analyses examining the relationships between the abilities/performance and the corresponding priorities can be placed in three groups. First, for some domains, priorities appear to be independent of the abilities/performance, as there was no linear or quadratic association between the factors. Specifically, there was no linear association between community living skills and community living priorities (r = −.09, p = .56, n = 45), job skills and job priorities (r = −.21, p = .20, n = 40), recreational skills and recreational priorities (r = .35, p = .02, n = 45), social skills and social priorities (r = .24, p = .12, n = 46), core academic skills and academic priorities (r = .02, p = .90, n = 43), and school behavior and academic priorities (r = −.14, p = .37, n = 43). Similarly, each of the quadratic terms for these pairs was not related to its respective outcome, as the percent of additional variance explained by this term was at or below 3% for all of the outcomes above and the smallest p-value associated with the test of this term was .23.

Second, some abilities/behaviors were linearly related to their respective priorities. Specifically, self-care skills were associated with the bodily function priorities (r = .55, p < .01, n = 48), motor skills were associated with motor skills priorities (r = .67, p < .01, n = 45), problem behavior was associated with problem behavior priorities (r = .55, p < .01, n = 44), and sleep disturbance was associated with the sleeping disturbance priorities (r = .50, p < .01, n = 44). Note that each of these associations was positive. Given the rating scale for these variables, this positive association means that priorities for each of these outcomes were smallest when children’s abilities/behaviors were highest, and parental priorities increased as children’s abilities diminished. Further, each of the quadratic terms for these pairs was not related to its respective outcome, as the percent of additional variance explained by this term was at or below 1% for all of the outcomes above, and the smallest p-value associated with the test of this term was .56.

Finally, for two of the domains, there was a quadratic relationship between abilities and priorities. For domestic living skills, the quadratic term was strongly associated with domestic priorities, as this term accounted for 12% of the variance in domestic living priorities (p = .01, n = 47). Also, for communication skills, the quadratic term accounted for 11% of the variation in communication priorities (p < .01, n = 43). While there was a quadratic relationship for each of these outcomes, the pattern of responses was different. Figure 1 shows the expected priorities as a function of children’s deficits for the domestic living domain. We used the term deficits here and in the following figure to ease interpretation of results. As can be seen in Fig. 1, parental priorities were lowest for children having either no or very high deficits. However, priorities were higher when children had mid-range deficits or emerging skills/behaviors.

Figure 2 shows the expected priorities as a function of children’s deficits for the communication domain. This figure shows that parental priorities were lowest for children having no deficits (or high abilities), increased markedly as deficits increased, and leveled off for children having greatest deficits (or lowest abilities). Note though, in contrast to the domestic living priorities, the priorities for the communication domain are fairly high for children having both mid-range and greater deficits. Thus, correlation and regression analyses suggest that when parental priorities are related to children’s abilities, parents generally have higher priorities when their children have mid-range or lower abilities, and have lower priorities when children exhibit a high level of ability.

Discussion

Fifty-four parents of children with cri-du-chat syndrome reported on their child’s level of ability for 44 adaptive skills and 10 problem behaviors and rated the extent to which each of these skills/behaviors was an educational priority. Two major findings emerged. First, the highest priority ratings were given to nine adaptive skills that represented four different adaptive behavior domains. Second, priority ratings were found to be either independent of children’s abilities or linearly or quadratically related to children’s abilities. These findings enable us to provide some preliminary commentary on the educational priorities that parents have for their children with cri-du-chat syndrome and the relationship of these priorities to the children’s behavioral strengths and deficits.

With respect to the identification of educational priorities, only 9 of the 44 (20%) adaptive skills (and none of the 10 problem behaviors) emerged as being high priorities (see Table 1). These nine skills were drawn from 4 of the 10 adaptive behavior domains. While this finding could indicate that the survey did not include very many skills/behaviors that were most relevant to the education of children with cri-du-chat syndrome, this result might alternatively suggest that these parents were relatively selective in their nomination of skills as high educational priorities. This latter interpretation is consistent with reviews of IEP content for individuals with developmental and physical disabilities, which have typically found that IEPs tend to prioritize a relatively small number (e.g., three to five) of skills/behaviors (Hunt and Farron-Davis 1992; Sigafoos et al. 1993). Most of the parents who responded to this survey reported that they had extensive knowledge of their child’s educational program. Thus, the relatively few number of high priority skills could reflect their knowledge that the children’s IEPs are likely to include a relatively small number of priority skills/behaviors at any one time.

In any event, results reported in Table 1 highlight nine specific areas that are likely to be of high educational priority for children with cri-du-chat syndrome. Special education professionals will therefore require competence in designing and implementing effective instruction to develop these types of skills in children with cri-du-chat syndrome. In light of this, programs to prepare special educational professionals for working with such children should include content related to the development of such competencies. Parents too should have ready access to objective and data-based—yet consumer-friendly—information on empirically-supported approaches for addressing these priorities.

Most of the high priority skills were drawn from the communication domain. The fact that training to develop communication skills was a high priority is consistent with the reported characteristics of cri-du-chat syndrome (Cornish and Bramble 2002; Ohr 1998). Interestingly, problem behaviors were not rated as a high priority overall. This does not indicate that the children had few problem behaviors because some parents did in fact rate certain specific problem behaviors as being a significant or major problem. For example, 27% of the parents reported that self-injury was a significant or major problem. Overall, however, treatment of problem behavior was not given high priority. This might reflect a perception that the treatment of problem behavior is not within the scope of the child’s educational program. If so, it would suggest a need to inform parents about the well-established effectiveness of behavioral/educational interventions for the treatment of problem behaviors in children with developmental disability syndromes (Sigafoos et al. 2003). Whether or not behavioral/educational interventions would be effective in the treatment of problem behaviors in children with cri-du-chat syndrome is an empirical question that remains open because there appears to be no such intervention studies reported in the literature. Given that problem behavior could represent a behavioral phenotype of cri-du-chat syndrome (Cornish and Bramble 2002), efficacy of contemporary behavioral/educational interventions for the treatment of problem behaviors in children with cri-du-chat syndrome would seem a critical area for future research.

With respect to the relation between parent educational priorities to the children’s relative strengths and deficits, we found no evidence to support a view that parents use a strengths-based logic (Seale and Nind 2009; Valencia 1997). Instead, parent priorities often reflected areas of either major deficits or emerging behaviors. Regarding the former, for the majority of skills/behaviors in the self-care, motor, and problem behavior domains, parents prioritized areas where the child showed major skill/behavioral deficits. The finding could indicate that parents followed a deficit- or needs-based logic for selecting some priorities. For example, toilet training was a major priority when children had major deficits in their toileting abilities and, in this sample, most of the children were said to require either considerable assistance with toileting or were totally dependent with respect to toileting.

Regarding the latter, for the domestic living and communication domains, parents prioritized areas where the child was already showing some level of development. The finding could indicate that parents identified some priorities based on evidence that the child might in fact be able to make progress in that area given that the child was already showing some development with respect to that area. This approach to prioritization of educational goals would appear consistent with Vygotsky’s (1978) notion of the zone of proximal development. In this study, it would appear that communication and domestic living skills were prioritized for education when they fell within the zone of proximal development. This interpretation could be viewed as a type of emergent-skills based logic for prioritization of educational goals.

The finding that priorities were often related to children’s deficits and emerging skills has implications for guiding the development of educational programs for children with cri-du-chat syndrome. Specifically, it would seem important for educators to undertake comprehensive assessments to identify children’s skills deficits and emergent behaviors. Information of this type may facilitate collaboration with parents to identify content for the child’s IEP (O’Reilly et al. 2007). To facilitate collaboration it would be interesting to determine if priority ratings differed between parents and teachers.

These findings must be interpreted with caution in light of several limitations. The main limitation of this study is that the sample may not have been representative, as evidenced by the lack of variability in the gender and education level of the respondents. Another limitation associated with Internet surveys is that they require the respondent to have Internet access (Hewson et al. 2003), which in this case may have restricted participation to Internet literate parents. Indeed the sample was highly educated, highly informed, involved in parent organizations, and mainly USA-based. A further limitation is the lack of prior empirical development of the survey. While the survey items were taken from relevant literature, it would seem to require further development given that our factor analysis suggested the need to restructure some items. Consequently, the present study should be seen as an initial trial of a new instrument.

Despite these limitations, this appears to be the first study aimed at identifying educational priorities for children with cri-du-chat syndrome and the first to investigate the relation between parents’ educational priorities and children’s ability/performance. Our results suggest nine areas that are likely to be high priorities and support the view that parent priorities are often based on the child’s deficits and emergent skills, rather than on the child’s strengths. An obvious area for future research would be to repeat this survey with other syndrome groups to determine if these findings are specific to cri-du-chat or might apply to a range of developmental disability syndromes. Differences in the educational priorities of parents across syndrome groups might be expected when a syndrome is associated with a specific behavioral phenotype (Walz and Benson 2002). Further research into the educational priorities for children with different syndromes may therefore be useful in guiding the design of educational programs that better match the presenting behavioral phenotype.

Notes

Available from the corresponding author.

References

Carr, A. & O’Reilly, G. (2007). Diagnosis, classification and epidemiology. In A. Carr, G. O’Reilly, P. Noonan Walsh & J. McEvoy (Eds.), The handbook of intellectual disability and clinical psychology practice (pp. 3–49). London: Routledge.

Cornish, K. & Bramble, D. (2002). Cri-du-chat syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlations and recommendations for clinical management. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 44, 494–497.

Ford, J. K., MacCallum, R. C., & Tait, M. (1986). The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: a critical review and analysis. Personnel Psychology, 39, 291–314.

Hewson, C., Yule, P., Laurent, D., & Vogel, C. (2003). Internet research methods: a practical guide for the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Higurashi, M., Oda, M., Iijma, K., Iijma, S., Takeshita, T., Watanabe, N., et al. (1990). Livebirth prevalence and follow-up of malformation syndromes in 27, 427 newborns. Brain Development, 12, 770–773.

Hunt, P. & Farron-Davis, F. (1992). A preliminary investigation of IEP quality and content associated with placement in general education versus special education classes. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 17, 247–253.

Lejeune, J., Lafourcade, J., Berger, R., Vialatte, J., Boeswillwald, M., Seringe, P., et al. (1963). Trois cas de la deletion partielle du bras court du chromosome 5. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaire des Seances de l’ Academie des Sciences: D. Sciences Naturelles, 257, 3098–3102.

Lovaas, O. I. (2003). Teaching individuals with developmental delays: Basic intervention techniques. Austin: Pro-Ed.

Niebuhr, E. (1978). The cri du chat syndrome. Human Genetics, 42, 143–156.

Ohr, P. S. (1998). Cri-du-chat syndrome. In L. Phelps (Ed.), Health-related disorders in children and adolescents: a guidebook for understanding and educating (pp. 192–196). Washington: American Psychological Association.

O’Reilly, M. F., O’Reilly, B., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G., Green, V. A., & Machalicek, W. (2007). Educational assessment. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of assessment in persons with intellectual disabilities (pp. 141–161). Boston: Academic.

Orelove, F. P. & Sobsey, D. (Eds.). (2004). Educating children with multiple disabilities: A collaborative approach (4th ed.). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Seale, J. & Nind, M. (Eds.). (2009). Understanding and promoting access for people with learning difficulties. London: Routledge.

Sigafoos, J., Elkins, J., Couzens, D., Gunn, S., Roberts, D., & Kerr, M. (1993). Analysis of IEP goals and classroom activities for children with multiple disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 8, 99–105.

Sigafoos, J., Arthur, M., & O’Reilly, M. (2003). Challenging behavior and developmental disability. London: Whurr.

Sigafoos, J., O’Reilly, M. F., & Lancioni, G. E. (2009). Editorial: Cri-du-chat. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 12, 119–121.

Snell, M. E. & Brown, F. (2006). Instruction of students with severe disabilities (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Person.

Stevens, J. P. (2009). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (5th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Valencia, R. R. (Ed.). (1997). The evolution of deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. London: Routledge.

Vaughn, S., Bos, C. S., & Schumm, J. S. (2007). Teaching students who are exceptional, diverse, and at risk in the general education classroom (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Walz, N. C. & Benson, B. A. (2002). Behavioral phenotypes in children with Down syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, or Angelman syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 14, 307–321.

World Health Organization (2003). ICF Checklist, Version 2.1a, Clinical form for international classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: Author.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pituch, K.A., Green, V.A., Didden, R. et al. Educational Priorities for Children with Cri-Du-Chat Syndrome. J Dev Phys Disabil 22, 65–81 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-009-9172-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-009-9172-6