Abstract

An hourly quantification of inorganic water-soluble PM10 ions and corresponding trace gases was performed using the Monitor for AeRosols and Gases in ambient Air (MARGA) at the TROPOS research site in Melpitz, Germany. The data availability amounts to over 80% for the five-year measurement period from 2010 to 2014. Comparisons were performed for the evaluation of the MARGA, resulting in coefficients of determinations (slopes) of 0.91 (0.90) for the measurements against the SO2 gas monitor, 0.84 (0.88), 0.79 (1.39), 0.85 (1.20) for the ACSM NO3 −, SO4 2− and NH4 + measurements, respectively, and 0.85 (0.65), 0.88 (0.68), 0.91 (0.83), 0.86 (0.82) for the filter measurements of Cl−, NO3 −, SO4 2− and NH4 +, respectively. A HONO comparison with a batch denuder shows large scatter (R2 = 0.41). The MARGA HNO3 is underestimated compared to a batch and coated denuder with shorter inlets (slopes of 0.16 and 0.08, respectively). Less NH3 was observed in coated denuders for high ambient concentrations. Long-time measurements show clear daily and seasonal variabilities. Potential Source Contribution Function (PSCF) analysis indicates the emission area of particulate ions Cl−, NO3 −, SO4 2−, NH4 +, K+ and gaseous SO2 to lie in eastern European countries, predominantly in wintertime. Coarse mode sea salt particles are transported from the North Sea to Melpitz. The particles at Melpitz are nearly neutralised with a mean molar ratio of 0.90 for the five-year study. A slight increase of the neutralization ratio over the last three years indicates a stronger decrease of the anthropogenically emitted NO3 − and SO4 2− compared to NH4 +.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Atmospheric processing of particles and their precursor gases from terrestrial, marine, and various anthropogenic primary and secondary sources determines the chemical composition and physical properties of particulate matter (PM). Varying meteorological conditions influence these physical and chemical properties in a very complex manner (Vecchi et al. 2007; Katzman et al. 2010), while the chemical composition of the gas and particle phase is the result of chemical conversions by gas phase, multiphase and heterogeneous reactions (Herrmann 2003; Hamed et al. 2010; Peter et al. 2010).

In Central Europe, a significant amount of particulate matter consists of inorganic ions, including nitrate (NO3 −), sulphate (SO4 2−), ammonium (NH4 +), and chloride (Cl−) (e.g., Neusüß et al. 2000; Spindler et al. 2013; Rogula-Kozlowska 2015). The quantification of these ions is predominantly performed by the standard method of filter sampling followed by offline analysis. Filter measurements offer the advantage of a widespread analysis of the chemical composition for the particle phase. However, sampling takes a long time (one to several days) and depends on the ambient PM concentrations; also, sampling may be subject to both positive and negative artifacts (Liu et al. 2014; Chow et al. 2015). It is essential to minimize such artifact formation and, additionally, investigate the change of pollutant concentrations at a higher time resolution for studying atmospheric processes.

Alternatives to particle measurements with a high time resolution are mass spectrometric systems, such as the Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (AMS) (e.g., Canagaratna et al. 2007) and the Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (ACSM) (e.g., Ng et al. 2011). Both instruments offer the chemical analysis of major non-refractory ions within submicron particles.

To allow for the quantification of refractory and coarse mode ions, particles are collected in a Steam-Jet Aerosol Collector (SJAC) in which the particles grow to droplets within a supersaturated environment (Khlystov et al. 1995). To avoid artifacts by corresponding water-soluble trace gases, a wet chemical denuder is placed in front of the SJAC. This methodology is also used within the Particle-Into-Liquid-Sampler (PILS) (Orsini et al. 2003; Sorooshian et al. 2006). Furthermore, the dissolved gases within the aqueous solution of the denuder can be quantitatively analyzed. This is, for example, applied in the wet annular denuder systems AMOR (Ammonia Monitor RIVM) of the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Dutch RIVM) (Wyers et al. 1993; Volten et al. 2012) or AMANDA (Ammonia Measurement by Annular Denuder sampling with online Analysis) described by Whitehead et al. (2008), Milford et al. (2009) and von Bobrutzki et al. (2010) in order to measure ambient ammonia (NH3) concentrations. Known instruments combining a denuder and SJAC are the GRAEGOR (Gradient of Aerosol and Gases Online Registrator) (Thomas et al. 2009) and the online Ambient Ion Monitor (AIM) (Ellis et al. 2011; VandenBoer et al. 2011; Markovic et al. 2012; Markovic et al. 2014; Sudheer et al. 2014; VandenBoer et al. 2014; Hsu and Clair 2015; Sudheer and Rengarajan 2015). Additionally, Trebs et al. (2004) used a denuder/SJAC system to perform aerosol measurements in the Amazon Basin. By coupling gas and particle measurements, phase partitioning processes of semivolatile particles and secondary inorganic aerosol formation can be investigated.

The commercial Monitor for AeRosols and Gases in ambient Air (MARGA) uses the same sampling combination of a SJAC and a Wet Rotating Denuder (WRD). ten Brink et al. (2007) and ten Brink et al. (2009) introduced the “MARGA-sizer”. These authors measured aerosols of different cut-off diameters at the meteorological tower of Cabauw in the Netherlands. In recent years, MARGA measurements were performed worldwide. Literature about MARGA measurements at different sites is summarized in Table 1.

With regards to available MARGA time series and measurement sites, long-term measurements of inorganic compounds in the gas and particle phase with a high time resolution are still missing for Central Europe. A typical reference site is the TROPOS research site in Melpitz, Germany. Daily PM10 filter measurements have been continuously performed at this site since 1992 (e.g. Spindler et al. 2013). Besides this, more intense measurement campaigns are performed. At this site, size-segregated impactor sampling (e.g. Herrmann et al. 2006) or online instrumentation like the AMS (Poulain et al. 2011; Poulain et al. 2014) were deployed. Measurements indicate that Melpitz is under the influence of different but quite specific air masses (Spindler et al. 2010; Spindler et al. 2013).

The present study intends to address two objectives. Firstly, we intend to follow water-soluble inorganic gases and PM10 particle composition by hourly time resolution in order to investigate diurnal variations. Secondly, we seek to evaluate the performance of the MARGA for a potential application at measurement sites within the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA). For this purpose, a large inter-comparison exercise was performed comparing the MARGA results with collocated and parallel measurements at the Melpitz site.

2 Measuring site and methods

2.1 Site description and meteorological parameters

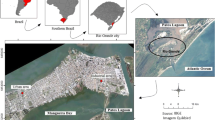

Measurements were performed at the research station of the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) in Melpitz (12°56′E, 51°32′N, 86 m a.s.l.). This rural field site is situated on a meadow and is surrounded by agricultural and forested areas. The station is part of the EMEP-Level 3 network (Co-operative Programme for Monitoring and Evaluation of the Long-Range Transmission of Air Pollutants in Europe) and the GAW (Global Atmosphere Watch) programme of WMO (World Meteorological Organization). A more detailed site description is given in Spindler et al. (2004) and Spindler et al. (2013).

Two different wind directions mainly influence the Melpitz site (Spindler et al. 2004). The dominating west wind reaches Melpitz after crossing a large area of Western Europe and the city of Leipzig, located about 50 km downwind of the site. These air masses are of marine origin. The second main wind direction is from the east and is mostly related to dry continental and – especially in winter – anthropogenically polluted air masses from Eastern Europe (Spindler et al. 2013).

Meteorological parameters are measured at the Melpitz site with the following instrumentation. In order to measure temperature and precipitation, instruments from the R.M. Young Company, U.S.A. (PT1000 and rain gauge) are used; relative humidity is measured using the CS215 sensor by Sensirion AG, Switzerland; and wind velocity and direction is measured by a WindSonic by Gill Instruments, UK. Global radiation and barometric pressure are recorded by a net radiometer CNR1 (Kipp&Zonen, The Netherlands) and a digital barometer (Vaisala, Germany), respectively.

2.2 Instrument description

2.2.1 MARGA

The hourly time-resolved quantification of water-soluble ions in PM10 (Cl−, NO3 −, SO4 2−, NH4 +, Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+) and their corresponding trace gases (HCl, HONO, HNO3, SO2, NH3) was realized by the commercial MARGA 1S ADI 2080 (Monitor for AeRosols and Gases in ambient Air, Applikon, The Netherlands) (ten Brink et al. 2007). An air pump draws air into a sample box after passing an inside Teflon-coated PM10 inlet (URG, Chapel Hill, located 5.5 m above ground) and a 3.5 m long polyethylene (PE) tube that are cleaned and replaced, respectively, at least every three month. The airflow of 1 m3 hr−1 is controlled by a Mass Flow Controller (MFC, Brooks, USA). Within the sample box, the air flows laminarily through a WRD in which water-soluble gases diffuse into an absorbing liquid at pH = 5.7 (Keuken et al. 1988; Wyers et al. 1993), consisting of double deionized water (>18 MΩcm) and 10 mg l−1 hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as an added biocide. The particles in the airflow pass the WRD, since their diffusion velocities are smaller than those of the gases, and reach the SJAC (Khlystov et al. 1995; Slanina et al. 2001). Within the SJAC, a supersaturation of water vapour causes the particle to grow into droplets. A cyclone collects the droplets containing the water-soluble inorganic ions. The aqueous samples of the WRD and the SJAC are continuously transported into the analytical box by two syringe pumps (25 ml). The gas and particle samples are both collected in the course of one hour. The samples are successively injected into two ion-chromatographs (IC) with conductivity detectors (Metrohm, Switzerland) for the online analysis of the anionic and cationic compounds in both phases. Lithium bromide is used as the internal standard. The volumes of the anion and cation injection loops are 250 μl and 500 μl, respectively. The anions are separated by a Metrosep A Supp 10 (75/4.0) column and a Na2CO3/Na2HCO3 (7 mM/8 mM) eluent. The intrinsic conductivity of the anion eluent has to be suppressed chemically using 0.35 M H3PO4. A Metrosep C4 (100/4.0) column and a 3.2 mM HNO3 eluent are used to separate the cations. The measured concentrations are corrected to standard conditions (20 °C, 1013 hPa). The lower detection limits and the inaccuracy are given in the Electronic Supplementary Material (Table S1). Blank measurements act only as indicator for contaminations as well as performance check-up and are not subtracted from real samples. The results are shown in the Electronic Supplementary Material as averages for every compound in Table S2. As the MARGA in Melpitz is built in 2009, it is not possible to check the performance of the MARGA by an extra valve with an external calibration standard.

2.2.2 PM10 filter measurements

PM10 particles are collected using a high-volume sampler DIGITEL DHA-80 (Digitel AG, Hegnau, Switzerland) on preheated quartz fibre filters (Munktell, Type MK360, Sweden). The sampling time lasts 24 hours from midnight to midnight with an airflow of 30 m3 hr.−1. The blank and loaded filters are conditioned for a period of 48–72 hours at (20 ± 1) °C and a relative humidity of (50 ± 5)% before being weighed by a microbalance (Mettler-Toledo; AT 261). Filters are extracted into ultrapure water (>18 MΩcm). Two ion chromatographs (ICS-3000, Dionex, USA) in the laboratory analyze the anions (column AS 18, eluent KOH) and cations (column CS 16, eluent methane sulfonic acid), respectively. A conductivity detector performs the cation analysis, while a coupled conductivity/UV-VIS detector is used for anion detection. Consequently, daily concentrations of Cl−, NO3 −, SO4 2−, NH4 +, Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+ are available for the whole MARGA measurement period (Spindler et al. 2010; Poulain et al. 2011; Spindler et al. 2013).

2.2.3 SO2 gas monitor

The gas analyzer APSA-360A (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) measures sulphur dioxide (SO2) concentrations every minute based on ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence during the five-year measurement period. The SO2 molecules are excited by UV radiation of a xenon lamp and emit light in the 220–420 nm wavelength range. The intensity of the fluorescence is proportional to the concentration.

2.2.4 NH3 cavity ring down spectroscopy (Picarro)

The Picarro G1103 gas analyzer (Picarro Inc., USA) measures hourly NH3 concentrations in the air from January 2010 to October 2011. The measurement utilizes the Cavity Ring Down Spectroscopy (CRDS, Berden et al. 2000) methodology. Within a resonator, a laser emits light, which is reflected by two mirrors. Besides a very small transmittance of the mirrors, NH3 absorbs the energy. Thus, after some time, the light intensity diminishes, and the intensity decay time can be used to quantify the concentration of NH3 (von Bobrutzki et al. 2010).

2.2.5 NH3 mini-denuder

Since April 2010, an integrating mini-denuder has been used for the quantification of NH3. NH3 diffuses on the walls of a citric acid coated denuder, in which a laminar airflow (0.43 m3 per day) exists. The NH3-content of the denuder was quantified by flow injection at the German Federal Environment Agency (UBA). The mini-denuders are provided by UBA and were changed weekly.

2.2.6 Rotating annular batch denuder

A rotating annular batch denuder was used for synchronous measurements of nitrous acid (HONO) and HNO3, which were absorbed into ultrapure water (Wyers et al. 1993). The batch denuder is an open system without any tubes or inlet in order to transport air directly inside. After a sampling time of one hour, the liquid is pumped into an auto-sampler. The hourly samples were taken for several summer and autumn days in 2011 and 2012 and were analyzed offline via ion chromatography with conductivity detectors (ICS-3000, Dionex, USA) at TROPOS.

2.2.7 Mini-denuder and mini-filter module (Midefix)

Two Midefix assemblies consisting of a mini-denuder and mini-filter module each were used for the measurement of gaseous NH3, SO2 and HNO3 as well as particulate NH4 +, SO4 2− and NO3 − (Dämmgen et al. 2010a, b) and was provided and analyzed by the Research Group for Environmental Monitoring (FUB) in Rapperswil, Switzerland. The two Midefix units were coated with potassium hydroxide (KOH) and phosphoric acid (H3PO4) in order to detect both anionic and cationic compounds, respectively. The trace gases are transported in a laminar airflow (0.5 m3 per day) and diffuse on the coating of a 22-cm-long glass tube. Particles were collected on the coated mini-filter. After a sampling period of two weeks, the concentrations of the gases and particles were determined by flow injection analysis via photometric detection (NH3, NH4 +) or ion chromatography. The Midefix unit was operated in Melpitz from November 2010 until February 2013.

2.2.8 Radial symmetric diffusive air sampler (Radiello®)

The commercialized radial symmetric diffusive sampler (Radiello®) measures gaseous compounds in the air. In this study, Radiello® samplers were used to determine NH3. Diffusive and adsorbing surfaces in these samplers are cylindrical and coaxial. A diffusive cylinder consists of microporous sintered polyethylene of an external diameter of 8 mm, a thickness of 1.7 mm, and an average porosity of 25 μm. It is coupled to an adsorbing cartridge with a radius of 2.9 mm, which is coated with H3PO4. The two parts create a fixed distance that forms the diffusive path. The diffuse sampler was installed in a suspension device, which was simultaneously acting as a shelter against the weather. After an exposition time of two weeks, the diffusive sampler was analyzed via flow injection with UV detection (Dämmgen et al. 2010a) by the FUB. Data were available for one year starting in February 2012.

2.2.9 ACSM

The Aerosol Chemical Speciation Monitor (ACSM, Aerodyne Inc., USA) analyzes the near PM1 chemical composition at Melpitz since June 2012. A more detailed description of the ACSM is given by Ng et al. (2011). After passing through the instrument inlet, the sampled air is focused into a narrow beam by an aerodynamic lens. The focused particle beam then reaches the vaporization and ionization chamber where the non-refractory part of the particles is vaporized by impaction on a surface heated to 600 °C. Nearby, an electron impact ionization source (70 eV) ionizes the vaporized particles before entering a quadrupole mass spectrometer. The scan of the mass-to-charge ratio covers the range of 12 to 148 amu and the time resolution of the ACSM is approximately 30 min.

2.3 Trajectory calculation and source contribution modelling

To generate 96 hours backward trajectories, the Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model was used (Stein et al. 2015). The trajectories were calculated for every hour for the entire measurement period of the MARGA starting at 500 m a.s.l.

The trajectories were combined with hourly MARGA data and the Potential Source Contribution Function (PSCF) is applied (Malm et al. 1985; Pekney et al. 2006; Xie and Berkowitz 2007; Hopke 2016) in order to study the most probable emission areas of the measured gases and PM10 compounds,. For every grid cell (i,j), the PSCF value is calculated by Eq. (1):

where n ij is the number of all trajectories that passes the grid cell (i,j), and m ij is the number of trajectories that show relatively high concentrations while passing the grid cell. The latter number can be varied by the use of different percentiles depending on the concentration course of the measured components. During the previous work, the 75th percentile was chosen for all species. Grid cells that have a lower number of trajectories were corrected by a weighting factor to reduce their effect. This calculation was performed using the software R (Mair et al. 2015) with the open access program package ‘Openair’ (Carslaw and Ropkins 2012).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Measurement period

Ion detections of 80% were achieved for the gases (HONO, HNO3, SO2, and NH3) and the main ions (NO3 −, SO4 2−, NH4 +) for the entire measurement period in Melpitz from 2010 until 2014. The single detection frequencies for every species are listed in Table 2. The low data coverage of the cations except NH4 + is attributed to concentrations below the detection limit in the hourly samples.

In autumn 2010, the MARGA participated in the HCCT 2010 campaign in Goldlauter for two months (Tilgner et al. 2014) and in an international CEN (European Committee for Standardization) field measurement campaign at the UBA site, Waldhof, from May until July 2014. Further data losses appeared due to maintenance and technical issues. For Mg2+ and Ca2+, the years 2010 and 2011 were deleted due to artifact formation (compare section 3.2.2).

3.2 Comparison of the MARGA measurements with other methods

In this study, several comparisons of the MARGA with other instruments were executed. As an overview of the duration of the single comparisons in the following section, Fig. 1 shows the realized measurement for each instrument.

As many instruments have time resolutions different to the MARGA, it is necessary to adjust the MARGA concentrations or vice versa. E.g., to obtain the diurnal concentration, the mean of the hourly MARGA data was calculated with the requirement that at least 75% of the averaged data per day are available and lie above the lower detection limit. Otherwise, we do not consider the diurnal concentration.

3.2.1 Comparison of gas phase measurements

SO2

The measurements using the MARGA system and the SO2 gas monitor in parallel for five years show a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.91 and a slope of 0.90. The results in Fig. 2a demonstrate that a trustworthy measurement of SO2 with the MARGA is possible for the whole concentration range. In Fig. 2b, a similar agreement can be achieved for the comparison with the mini-denuder unit of the Midefix for the two-year measurement period (slope 0.98, R2 = 0.73). These results agree with those of Rumsey et al. (2014) for the comparison with a coated denuder.

HONO

The comparison of a rotating annular batch denuder with the MARGA for HONO measurements in Fig. 3 results in a slope of 1.10 and shows a large scatter field (R2 = 0.41). Acker et al. (2004) used a wet effluent diffusion denuder (WEDD) and a rotating wet annular denuder (RWAN) for an eight-day comparison; the latter is similar to the WRD that is part of the MARGA. Pure water and a 0.0005 M K2CO3 solution were chosen as denuder liquids, respectively. These authors found analogous results with a slope of 1.028 and a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.63. Also, Genfa et al. (2003) compared two denuders (rotating wet annular denuder and wet parallel plate denuder with Na2CO3 and H2O2 solutions acting as absorbers, respectively) during the Atlanta Supersite study 1999 and found a coefficient of determination of 0.78 with a slope near unity. Absorber liquids with different pH values could explain the scattering in both studies. Spindler et al. (2003) used alkaline denuders and found several positive artifacts that could appear due to heterogeneous interactions of NO2 and H2O as well as reaction of NO2 and SO2 in water. In addition, the HONO sampling efficiency can be increased by the use of alkaline absorber solutions. In the present work, the compared denuders have the same pH of 5.7. A cause for the weak correlation could be found in the offline analysis for the batch denuder and in the heterogeneous and liquid phase reactions, which could slightly vary for each denuder. The additional H2O2 in the MARGA denuder could influence such reactions as well.

Stutz et al. (2010) mentioned that HONO measurements using most of the in-situ methods are problematic. Denuder techniques can measure higher values than optical measurement systems, such as, e.g., the Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS). This is due to the fact that heterogeneous reactions on the wet surfaces can form additional nitrite (Kleffmann and Wiesen 2008). However, previous works of Spindler et al. (2003) and Acker et al. (2006) found agreements between the chemical denuder technique and the DOAS. Spindler et al. (2003) showed a relatively good agreement between both methods but also took into account the different measurement methods of both techniques. The denuder measures the concentration at one point whereas the DOAS is an integrating system that works over a long distance (several hundred meters). In the nighttime, a HONO gradient can be formed due to the appearance of an inversion layer. If the integrating path of the DOAS crosses different heights, a comparison with the point measurement of a denuder is difficult. Therefore, Acker et al. (2006) compared the DOAS and a denuder (here with a neutral absorbance solution) during well-mixed atmospheric conditions with the result of successful high-time resolved, sensitive, and comparable measurements of HONO. However, the cited authors also concluded that spectroscopic methods like DOAS show advantages when studying reactive species as HONO. Wang et al. (2013b) described the DOAS as highly selective, free of chemical interferences, and (in case of a well-mixed atmosphere) free of sampling artifacts.

HNO3

The MARGA system was compared for HNO3 with similar denuder instruments. Both the rotating annular batch denuder (slope = 0.16, R2 = 0.45) and the denuder unit of the Midefix (slope = 0.08, R2 = 0.06) show clear deviations from the measured HNO3 concentrations by the MARGA (Fig. 4a,b).

An obvious underestimation of HNO3 by the MARGA is observed in the comparison. The most likely reason is the “sticky” behavior of HNO3 (Rumsey et al. 2014). While the sampled air is directly pumped in the rotating annular batch denuder and the Midefix, the inlet and the WRD of the MARGA are connected through a 3.5 m long PE tube in which HNO3 can adsorb onto the walls. Neuman et al. (1999) compared different tubing materials for HNO3 measurements in the laboratory, with the result that the least adsorption occurs using a perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) Teflon tubing above 10 °C. However, it was remarked that a high relative humidity strengthens the adsorption, which is often in conflict with field measurements. Regarding the comparison of the denuder instruments, the best solution would be to draw air directly into the MARGA system without an inlet. However, this would lead to a direct penetration of particles larger than 10 μm, and a strong influence of the prevailing meteorological conditions (e.g., frost and rain) could very quickly damage the MARGA system. Additionally, positive artifacts can occur for the HNO3 detection by the MARGA system due to the heterogeneous reaction of N2O5 to HNO3 mainly during nighttime (Phillips et al. 2013). This group found high sensitivities to N2O5 for wet chemical denuders and alkaline denuders. As the latter effect would occur in all denuders in this comparison, it is not the reason for the observed underestimation of the MARGA HNO3 measurement.

NH3

Similar to HNO3, a comparison of NH3 MARGA measurements with other sampling instruments is essential as NH3 can interact with the walls of the inlet due to its “sticky” behavior (von Bobrutzki et al. 2010). Norman et al. (2009) noted that cooling on the outside of the inlet can favour condensation within the tubing. This could lead to an adsorption of NH3. It was suggested that the best way to avoid condensation is heating the inlet to some small amount above the ambient temperature. In Melpitz, a pipe enclosing the sampling tube is continuously ventilated to avoid cooling processes by rain and lower temperatures outside the air-conditioned container. Additionally, the high flow rate of the MARGA shortens the residence time of gaseous NH3 inside the inlet tube and reduces the wall interactions. Whitehead et al. (2008) found that PE is the best material for the sampling of NH3. The results of the comparisons in this work indicate that a wall loss of NH3 is negligible due to higher MARGA concentrations compared to other instruments.

Volten et al. (2012) compared miniDOAS and AMOR, the latter using similar sampling methods as the MARGA. Both instruments had a time resolution of one minute. For high time resolutions, the authors found, firstly, a delay of the peaks in the AMOR data due to the turnover time of the liquid inside the denuder. Secondly, the AMOR could reach neither very low nor very high NH3 concentrations. It was guessed that this could likely be the result of adsorption and desorption of NH3 in the inlet. Daily averages of both instruments show a good agreement for the NH3 variations, but with higher AMOR NH3 concentrations due to possible memory effects in the inlet. Thus, in this work a memory effect for the MARGA should always be considered.

In Figs. 5 and 6, the comparison of the MARGA with the optical Picarro system bares discrepancies in the measurement of NH3 (R2 = 0.50). The Picarro detects up to 3 μg m−3 more NH3 than the MARGA for low NH3 concentrations (< 5 μg m−3). This behavior could be explained by the use of a prefilter system in the Picarro instrument in order to avoid the penetration of particles into the sensitive resonator. Ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) deposits onto the inlet filter surface and can afterwards evaporate due to its semi-volatility, depending on ambient temperature and relative humidity (Schaap et al. 2004; Keck and Wittmaack 2005; Plessow et al. 2005). The evaporated gaseous NH3 is then measured by the Picarro system, leading to higher concentrations compared to the concentrations measured with the MARGA directly. This could explain the negative intercept of −7.35. For higher NH3 concentrations, an opposite behavior is recognizable. For NH3 concentrations greater than 15 μg m−3, the Picarro system shows a significant underestimation (Fig. 6). A possible reason could be the formation of negative artifacts due to the prefilter. Acidic particles collected on the prefilter could lead to a significant loss of alkaline gaseous NH3. In addition, the Picarro shows a very slow decrease after the detection of high NH3 concentrations. During this time, the MARGA shows a much faster decrease with sharp peaks and more fluctuations. This sluggish behavior of the CRDS method is a result of the combination of both Picarro artifacts. Adsorbed NH3 desorbs when higher temperatures or lower humidities and lower environmental NH3 concentrations are given. The similar artifact with a prefilter was also mentioned by von Bobrutzki et al. (2010).

A comparison of different NH3 measurement techniques by Schwab et al. (2007) suggests that denuder measurements show a very long time response. However, the NH3 concentrations were measured every second via a fluorescence method and were reported as minute averages. The hourly MARGA data do not provide this high time resolution and a long time response cannot be observed.

As opposed to the MARGA NH3 data comparison with the Picarro NH3 measurements, the chemical analysis of the coated surfaces (NH3 mini-denuder, Midefix and Radiello®) show better correlations. Those are summarized in Table 3. However, the slopes from 1.30 to 1.53 show that concentrations measured by coating techniques are generally lower than those of MARGA. In times of high NH3 concentrations, these instruments measure less NH3 than the MARGA. Regarding the diffuse samplers, it could be possible that the duration time is too short in times of high or strongly fluctuating concentrations. Nevertheless, the maximal saturation of the Radiello® is around 500 μg m−3 for a biweekly exposition, which was never exceeded during the comparison period.

In contrast, Rumsey et al. (2014) observed higher NH3 concentrations for the coated denuder measurements, which were sampled every 12 h. The cited authors try to explain their slopes with the “sticky” property of NH3, similar to HNO3, as well as variability in the denuder blank and possible inaccuracy of the external standard offset (Rumsey et al. 2014). Possibly, the different slopes can be explained by the fact that the measured NH3 concentrations in this work were up to 10 times higher than the measured NH3 by Rumsey et al. (2014).

Norman et al. (2009) compared the MARGA related GREAGOR system with an Automated Ammonia Analyzer (AiRRmonia) and a modified Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometer (PTR-MS) for five days of data. It was concluded that all instruments are suitable for atmospheric NH3 measurements. In addition, von Bobrutzki et al. (2010) found good long-term stability for wet chemistry instruments.

3.2.2 Comparison of particle phase measurements

MARGA vs. ACSM

The parameters for the orthogonal regressions for the comparison of the MARGA with the ACSM are summarized in Table 4. It should be noted again that different cut-off diameters for the particle composition analysis were used for the MARGA (PM10) and the ACSM (PM1). For SO4 2− and NH4 +, slopes of 1.39 and 1.20 were achieved, respectively. This indicates that there is a larger fraction of both ions in the coarse mode (PM1-PM10).

Higher NO3 − concentrations were detected by the ACSM in comparison with the MARGA. The slope (0.88) is comparable with the study of Makkonen et al. (2014) (0.819), where a MARGA was compared with an AMS, which used a similar sampling and detection technology as the ACSM (Ng et al. 2011). As suggested by Makkonen et al. (2014), this offset could be explained either by the measurement of organic nitrates with the ACSM/AMS or a lower response of the MARGA for these compounds. For periods of low NO3 − concentrations, those measured by the MARGA tend to be slightly higher (intercept: 0.39).

Both instruments agree, but there are periods when the MARGA strongly overestimates the ACSM NO3 − concentration (Fig. 7). During the 1st, 6th, 7th, 15th, and 16th September 2012, the site was influenced by westerly winds that transport marine air masses to the sampling site, as it can be illustrated by looking at the increase of the sodium concentration during these days. Therefore, the measured nitrate might not only include ammonium nitrate but also sodium nitrate (NaNO3), resulting in the reaction of sodium chloride (NaCl) with HNO3 when marine air masses crossed some polluted areas (Finlayson-Pitts and Pitts 1986; Pio and Lopes 1998). Similar to sea salt, NaNO3 is a very low-volatile compound that evaporates at temperatures above 600 °C; therefore, it is quite difficult to detect this salt by ACSM. Moreover, NaNO3 is principally present in the coarse mode, which is out of the ACSM size range. Consequently, the discrepancy between the two instruments during marine air mass influence might result in a size cutting effect, while it may also indicate the presence of two types of nitrate salts.

Some comparisons between AMS and MARGA or MARGA-related instruments were described. Mensah et al. (2012) compared a so-called “MARGA-sizer” with which various particle sizes can be analyzed. For the 1-μm channel of the MARGA-sizer, the measured concentrations of the different ions were on average a factor of 1.6 higher in comparison to the AMS. Better ratios could be achieved with the 0.56-μm channel, but the coefficients of determination decreased. The cited authors concluded that the deviations between the AMS and the MARGA-sizer are possible due to the different sample heights and potential losses within the inlet. Markovic et al. (2012) compared the AMS with an Ambient Ion Monitor-Ion Chromatograph (AIM-IC) with a PM2.5 inlet. For all ions, more highly averaged mass loadings were detected with the AMS. The authors hypothesized that if all particles are found in PM1 and not all compounds are solved in water, then the AMS measures higher concentrations. Additionally, two more explanations were mentioned. First, the AMS data were corrected by the collection efficiency. Second, the collection efficiency for particles of the AIM-IC was lower than 100%. Nevertheless, this study and both mentioned groups conclude a qualitatively good agreement between MARGA and AMS (Mensah et al. 2012) as well as accurate measurements of the particulate NO3 −, SO4 2−, and NH4 + with the AIM-IC (Markovic et al. 2012).

MARGA vs. filter measurements

Table 5 shows the results of the orthogonal regression of the data for the measurement period.

For the PM10 filter, coefficients of determination of 0.85–0.91 were obtained for the ions Cl−, NO3 −, SO4 2− and NH4 +. Slopes from 0.65 to 0.83 indicate an underestimation of the concentration by the MARGA compared to filters. A possible reason for this could be the adsorption of their gaseous forms onto the filter surface, whereby the offline analysis detects higher amounts of these ions. However, for NO3 −, a converse behavior can be observed, as shown in Fig. 8a,b. The correlation for NO3 − varies between summer (April–September; R2 = 0.76, slope = 0.66) and winter (October–March; R2 = 0.88, slope = 0.71). In summer, when the absolute concentration of nitrate is lower than in winter, a negative artifact exists for the filter sampling. This is because of the high volatility of NH4NO3 (Schaap et al. 2004; Keck and Wittmaack 2005; Plessow et al. 2005), that evaporates to NH3 and HNO3 during higher temperatures and lower humidities in summer. The ACSM data are also shown in Fig. 8a, b. In summer, the ASCM shows higher NO3 − values compared to the filter, although the ACSM collects a smaller size fraction. In winter, the analysis of the PM10 filter shows slightly higher concentrations compared to MARGA and ACSM.

Interestingly, the slope between MARGA and Midefix for NO3 − is close to unity (0.91) with nearly the same coefficients of determination. The Midefix was operated from November 2010 to February 2013 and covered two winters and summers. A summer/winter dependence for the comparison with the MARGA as for the PM10 filter cannot be detected. Possibly, the coating of the mini-filter suppresses the loss due to evaporation.

Rumsey et al. (2014) mentioned that a contamination with bacteria in the WRD and SJAC could lead to a depletion of NH4 +. However, by means of the H2O2 used as biocide and regular cleaning of the WRD and SJAC at least every two weeks, a bacterial development could be avoided or strongly limited, and therefore this artifact may be minor. A microbiological depletion of NH4 + would result in an increase of NO3 − (Rumsey et al. 2014), which has not been observed, neither in the latter nor in the present study.

The Midefix measurements for NH4 + and SO4 2− concentrations show higher deviations and an underestimation compared to the MARGA. The Midefix detects more NH4 + than the measurements performed by the MARGA for the whole measurement period; this could be explained by the absorption of NH3 on the filter surface, which had likely not been collected by the preceding coated denuder.

The concentrations of the non-NH4 + cations often remained below the detection limit. This results in a smaller number of compared points (n) by a factor of five to ten compared to the main ions (Table 5). Initial concentrations of magnesium (Mg2+) and calcium (Ca2+) show a significant overestimation in 2010 and 2011. It emerged that over time both ions accumulate inside of the cation injection loop and can detach and spread again during later samples. Since 2012, the loops within the Melpitz MARGA have been renewed on a quarterly basis at the least. This issue is also described by Makkonen et al. (2012). Eventually, the years 2010 and 2011 were not used for comparison and further analysis.

Weak correlations for the non-NH4 + cations were found with an underestimation by the MARGA measurements, except for Ca2+. A possible reason for the underestimation of the concentrations can be found in Thomas et al. (2009). The cited authors used the GRAEGOR system for the measurement of ions in the gas and particle phase and reported that 3.3% of PM10 are also detected within the WRD samples due to gravitational processes.

Nevertheless, the regressions for these ions in Makkonen et al. (2012) are comparable to those in this study. In the course of a subsequent study, the cation loop was replaced by a pre-concentration column, by means of which slopes near unity and better coefficients of determinations for potassium (K+) and Na+ could be observed. The measured concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ were very low and led to weaker coefficients of determination but better slopes close to unity during their measurement period (Makkonen et al. 2014). The use of pre-concentration columns was not realized in Melpitz to avoid a change in the well-defined and complex analytical method used for this long-term study.

3.3 Results of the five-year measurement period

The hourly MARGA data allow us to investigate the daily cycle of the quantified concentrations in the gas and particle phase and their seasonal variations. As additional information, the maximum concentrations of each gaseous and particulate compound is given in the Electronic Supplementary Material in Table S1. The PSCF method visualizes the most probable geographical emission areas of each species. However, this method of calculation and modelling is more appropriate for the particle phase as the measured gases have shorter atmospheric lifetimes.

3.3.1 Gases

The measurement series for the trace gases as weekly averages and the diurnal variations for each season over the entire sampling period are plotted in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively.

The most distinct cycle for HNO3 appears during the springtime (Fig. 10a). The highest springtime concentrations were measured during the time period from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM CET. These concentrations are in agreement with the highest formation rate during daytime. Photolytically produced OH radicals react with nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and form HNO3 (Seinfeld and Pandis 2006; Griffith et al. 2015). This explains that the highest concentrations occur in summer as shown in Fig. 9. A possible photolysis of HNO3 as a sink can be neglected in the troposphere since the photolysis is very slow (Möller 2003). The fast deposition onto surfaces and droplets is the main sink of HNO3 (Ferm and Hellsten 2012), especially during nighttime. Another sink might be the nocturnal reaction of NO3 radicals and alkanes. However, the rate constant is low and should be of minor importance (Seinfeld and Pandis 2006). In presence of NH3, NH4NO3 can be formed depending on temperature and humidity (Möller 2003; Acker et al. 2006). As discussed in the previous section, the MARGA HNO3 concentrations should be used critically because of its sticky behaviour.

Clear diurnal variations for HONO are observable, which are comparable to the ones reported by Pinto et al. (2014) and Acker et al. (2006), despite their known artifacts (see chapter 3.2.1). Figure 10b illustrates the HONO concentration differences between summertime and wintertime. Nighttime concentrations during the summer are on average twice as high as nighttime concentrations in winter. Possibly, the longer daylight hours in summer and more intense solar radiation favor the photolytic production of OH radicals. In the evening, in the presence of NO and absence of solar radiation, the radicals can react with HONO. In autumn and winter, the diurnal cycle is less pronounced than during spring and summer. At sunrise, the photolysis of HONO results in a decrease of measured concentrations. Beside possible positive artifacts caused by wet chemical sampling, HONO daytime sources also exist and explain low HONO concentrations despite of a strong photolysis. Several HONO daytime sources were discussed in literature (Li et al. 2014; Michoud et al. 2014; Spataro and Ianniello 2014; VandenBoer et al. 2014).

SO2 as an anthropogenically emitted trace gas shows clear diurnal cycles in all seasons, as shown in Fig. 10c. Regarding the diurnal cycle of SO2 for all seasons, the highest concentrations were measured in winter due to emissions by domestic heating and coal-fired power plants (Hamed et al. 2010) as well as enrichment in the inversion layer. Furthermore, for all seasons the highest concentrations occurred at noon, which is in agreement with the measurements performed by Henschel et al. (2013). The SO2 noontime peak was investigated by Xu et al. (2014) for measurements performed in the North China Plain (NCP). The group tried to explain the peaks observed in the NCP with different reasons. For Melpitz, the most dominant enrichment processes of SO2 probably lie in the transport into higher layers and down-mixing in the morning due to the break-up of the inversion layer by solar radiation.

After reaching the noontime peak, the SO2 concentration decreases during afternoon. This decline starts earlier during summer and spring than it does during autumn and winter. The atmospheric oxidation processes of SO2 lead to a formation of gaseous sulfuric acid (H2SO4) or particulate SO4 2− (Jones and Harrison 2011).

As SO2 has a tropospheric lifetime of one week based on the rate constant for the reaction with OH radicals (Seinfeld and Pandis 2006), a long-range transport can occur effectively, making it possible to calculate the original emission area from which the SO2 was transported to Melpitz. In Fig. 11, the PSCF analysis indicates South Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and possibly Austria as emitters of this trace gas that emerges mainly as a result of combustion processes. In addition, the alpine regions as well as Eastern Poland seem to be likely emitters of SO2 as well. However, the results of these PSCF plots are influenced by the respective form of the trajectories. For example, the air parcel over Eastern Poland is strongly polluted. Anticyclonic conditions force the air parcel to overflow Czech Republic and then approach Melpitz from a southeasterly direction. Further “polluted” trajectories from other directions can overflow Czech Republic in addition, leading to a high density of “polluted” trajectories. While the PSCF model maps the source potential of particular area it does not indicate the contribution of the source area to the measured concentrations (Hopke 2016).

As shown in Fig. 10d, the nocturnal concentrations of hydrochloric acid (HCl) range between 0.1 and 0.15 μg m−3 for all seasons, whereas the maximum daytime concentrations vary from 0.2 μg m−3 (in winter) to 0.4 μg m−3 (in summer), as a result of a higher radiation budget (see also Fig. 9). A shift in time between winter (12:00 AM, CET) and summer (4:00 PM, CET) was found for the observed maximum concentrations. The main contributions to the increase of HCl concentrations are to be found in surface reactions of H2SO4 and HNO3 with sea salt aerosols (Pio and Lopes 1998; Seinfeld and Pandis 2006). Both acids reach their highest tropospheric concentrations after sunrise due to photochemical formations or meteorological influences. As SO2 and HNO3 reach their highest concentrations during daytime, it seems that their presence, SO2 acting as a precursor of H2SO4, is essential to HCl formation in the afternoon. An additional HCl daytime source can be found in the evaporation of volatile particulate ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) (Pio and Harrison 1987).

The lowest concentrations as well as the least distinct diurnal cycle for NH3 can be found in winter (Fig. 10e). For the other seasons, a significant increase during the morning hours was observed, with averaged maximum concentrations of 10 μg m−3 detected during spring. Figure 12 shows averaged NH3 concentrations as a function of temperature, indicating a quick increase of NH3 between 0 °C and 10 °C. This has several reasons: First, with increasing temperature, wet surfaces begin to evaporate dissolved NH3 (Hesterberg et al. 1996). Second, with increasing temperature at the earth’s surface, air masses become more labile, resulting in vertical mixing. Thus, volatile ammonium salts like NH4Cl and NH4NO3 reach Melpitz through long-range transport and possibly mix into warmer near surface air masses, where the salts evaporate to NH3, HNO3 and HCl. These higher NH3 concentrations during the early morning hours, caused by turbulent transport, often occurred simultaneously with an increase in SO2. The third reason can be found in the end of the legal blocking period (1st of March) for liquid manure fertilization in the surroundings of the TROPOS research station in Melpitz. Fertilization is not allowed as long as the soil is still frozen or saturated with water. Only at positive temperatures and when dry soil surfaces are given, liquid manure may be used. The latter also explains the high concentrations observed during spring (Ferm and Hellsten 2012). The last possibility that has to be taken into account when considering the peak in the morning is a possible memory effect of the inlet system (see chapter 3.2.1). Increasing temperatures in the morning could then lead to an evaporation of deposited NH3 within the inlet.

3.3.2 Particulate ions

Figure 15a shows two important sources of Cl− occurring in different temperature intervals. At below −8 °C, the averaged Cl− concentrations vary between 0.4 and 0.6 μg m−3A second maximum of the Cl− concentrations with 0.5 μg m−3 exists at temperatures slightly above zero. Both maxima have individual sources. In addition, the diurnal variability for the different seasons is shown in Fig. 16a.

For temperatures <−8 °C, the sampled aerosol can consist of Cl− originating from the combustion of Cl−-containing coal in Eastern Europe (Xie et al. 1997; McCulloch et al. 1999; Spindler et al. 2013; Tang et al. 2015). Consistently, at very cold temperatures, the predominant air mass inflow is coming from an easterly direction, as shown in Fig. 15b. The figure shows the frequency of a respectively observed wind direction as a function of Cl− occurrence. In winter, an additional local contribution to the higher Cl− concentrations lies in the reemission of road salt used for the de-icing of streets. When observing measured Cl− in relation to wind direction and wind speed (Figs. 15c,d), the highest averaged concentrations can be detected at northeasterly and southwesterly winds. Relative to Melpitz, there are two main roads situated in this direction that are gritted with salt in winter. However, influences originating from the cities of Torgau and Leipzig, which are also located in these directions, can also contribute to the amount of Cl− measured in Melpitz. These findings are in agreement with Fig. 16a, showing high Cl− concentrations (0.4 μg m−3) during winter.

The second maximum is observed at moderate temperatures (Fig. 15a) and can be explained by the sum of two effects. Firstly, similarly to NH3 (see section 3.1.1), the Cl− concentrations are high at temperatures over 0 °C. This parallel increase leads to the conclusion that, again, the agricultural use of Cl− (artificial fertilizer) explains its high concentrations in spring (Fig. 16a). Secondly, the increase of Cl− at moderate temperatures indicates more marine influences. Sea salt aerosol originating from long-range transport consists mainly of Cl− that is measured in Melpitz. The highest wind speeds measured in Melpitz occurred mainly during autumn and winter and from westerly directions, which explains the dominant Cl− peak at moderate temperatures.

The lowest Cl− concentrations occurred in summer, with 0.2 μg m−3. Pio and Lopes (1998) found that, especially in summer, a loss of Cl− within the particulate matter due to volatilization can be observed. The degassing of chlorine takes place through reactions with acidic sulphur compounds for fine particles and HNO3 for the course mode.

The PSCF analysis for the five-year measurement period highlighted the marine origin of Cl− as well as its emission from coal combustion. Figure 17a clearly indicates marine air masses from the North Sea as one of the main contributors to the analyzed Cl− concentrations in Melpitz. A second emission area covers a large area including Austria, Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia that contributes to anthropogenic emissions. Thereby, the shift in the respective contribution factors is clearly identifiable for the different seasons (Fig. 18). In spring, the dominant source of Cl− can be found in marine aerosols; anthropogenic aerosols from the east however only give minor contributions. In summer, only the presence of sea salt adds to the measured concentrations in Melpitz. Contribution by the eastern component starts to increase again in autumn and grows to be the major contributor in winter.

The diurnal cycles of NO3 − (Fig. 16b) and NH4 + (Fig. 16c) show their highest values in the morning, caused by the start of vertical mixing, and a decrease in the afternoon. This course in time is equally pronounced during every season. In the fine mode, NO3 − is mainly bound in the form of NH4NO3, which is dependent on the gas phase precursor concentrations, temperature, humidity, and aerosol chemical composition (Poulain et al. 2011; Twigg et al. 2015). The volatile behaviour of NH4NO3 results in the formation of the gaseous compounds HNO3 and NH3 for higher temperatures and low humidity. In winter, NH4NO3 exists predominantly in the particle phase (Seinfeld and Pandis 2006), explaining higher concentrations for NO3 − and NH4 + (Fig. 16b,c). High values of NO3 − and NH4 + in spring are attributed to agricultural fertilization.

In winter, SO4 2− reaches its highest concentrations but shows no diurnal variation (Fig. 16d). The anthropogenic SO4 2− is emitted from domestic heating processes and can, additionally, be enriched in the atmospheric boundary layer. Similar results were reported by Spindler et al. (1999) and Cyrys et al. (1995). A slight increase of the SO4 2− concentration at noon and during the afternoon is recognizable for the other seasons. This is in good agreement with the findings in the prior chapter. The formation of SO4 2− as a result of atmospheric oxidation processes of SO2 can explain this peak during daytime.

A relationship between the measured NO3 −, SO4 2− and NH4 + can be determined through the calculation of the most probable emission areas. Exhibiting red and violet colors in Fig. 17b-d, and nearly the same spatial extent, all three ions show high concentrations when air mass transport from easterly directions is given. Similar to SO2 and anthropogenic Cl−, the highest probabilities with over 50%, 30% and 40% for SO4 2−, NO3 − and NH4 +, respectively, were calculated for areas stretching over the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Southern Poland. Moreover, all of these compounds show their highest concentrations in the winter months (Figs. 9 and 13). Thermo-stable ammonium sulphate shows the lowest vapor pressure of all ammonium salts and is the first to form (Ferm 1998). In addition, the thermo-volatile NH4NO3 exists in the particle phase in winter. These salts can reach Melpitz through long-range transport. Additionally, fine mode NO3 − is formed during the oxidation of NOx emissions of anthropogenic origin, while the chloride-nitrate exchange leads to the formation of course mode NO3 − particles, even over Central and Western Europe (Dasgupta et al. 2007; Twigg et al. 2015). This can explain the high emission probability shown in Fig. 17b. Ferm and Hellsten (2012) measured particulate ion concentrations in several sites in Sweden and observed an inflow of high NO3 −, NH4 + and SO4 2− concentrations in particles transported from the south. These ions were transported in the solid phase over long distances from Central Europe, since these particles have a lower deposition velocity than their gaseous precursors in Central Europe. In Ferm (1998), the averaged NH4 + concentrations of several European sites were shown for different wind sectors. Thereby, the western and central European sites all indicate an easterly origin of NH4 +. The results of both studies agree with the air mass origin of NH4 + found in the present study.

The number of detected non-NH4 + cations is lower in comparison to the main ions (see chapter 3.1). A clear diurnal cycle for K+ cannot be recognized in Fig. 16e , but in winter, higher concentrations could be observed at midnight and the following hours. However, these high mean values during nighttime are primarily the result of only three days in the five-year long-time period that showed high K+ concentrations. On New Year’s Eve, fireworks emit large amounts of potassium nitrate into the troposphere. This could be observed for the years 2010, 2011 and 2014. During these days in 2012 and 2013, the MARGA in Melpitz was out of service. The impact of fireworks on the atmospheric pollution was also investigated by means of the MARGA by Wen and Chen (2013). Therein, the K+ concentration was used as a tracer for firework events. Generally, higher K+ concentrations were observed during the winter months. The main K+ source is thereby wood combustion. The PSCF calculation for K+ (Fig. 17e) ascribed the main emission areas to regions situated to the east of Melpitz and the Alps, which indicates an anthropogenic source, as domestic heating with wood is more common in these regions.

For the sea salt tracers Na+ and Mg2+ (Perrino et al. 2010), a marine origin becomes obvious in Fig. 17f, g. Both are transported to the measurement site in form of NaCl and magnesium chloride (MgCl2), or processed as NaNO3, with westerly winds. Correspondingly, the calculated maps of their emission areas show their highest concentrations above the North Sea and the northern Atlantic Ocean. This is in good agreement with analysis made for Cl−. (Fig. 17a). Additionally, high Mg2+ concentrations in winter (Fig. 16f) could be attributed to the de-icing of streets using road salt, acting as a source in the surroundings.

Very high concentrations of Ca2+ were observed in spring. In comparison to the detected Ca2+ concentrations in spring, as shown in Fig. 16g, the concentrations measured in other seasons were lower by a factor of 2.5. As both Mg2+ and Ca2+ show high concentrations in spring, a related effect could be possible. These high values were detected in spring 2012 (Fig. 14). The possibility that high concentrations occurred due to the formation of artifacts within the sample loop can be neglected as they have been exchanged periodically since 2012. Another possible reason could be the application of mineral fertilizer in agriculture and forestry in 2012.

(a) Influence of temperature on Cl− concentration. The points represent the averaged concentrations per degree with the standard deviation as error bars. The number of data points n considered for averaging is displayed as the line plot (right ordinate). (b) Wind dependence on the frequency, (c) Cl− concentration, and (d) wind speed for the temperature interval of <−8 °C in Melpitz during the measurement period

PSCF analysis of (a) Cl−, (b) NO3 −, (c) NH4 +, (d) SO4 2−, (e) K+, (f) Na+ and (g) Mg2+ over five years calculated using the open access R package ‘Openair’. The colors correspond to the probability that the respective region is the most likely emission area of the measured particulate ions in Melpitz (black point)

PSCF analysis of Cl− in (a) spring, (b) summer, (c) autumn, and (d) winter over five years calculated using the open access R package ‘Openair’. The colors correspond to the probability that the respective reason is the most likely emission area of the measured particulate ions in Melpitz (black point)

Further sources of particulate Ca2+ can be found in the re-emission of calcium carbonate and calcium sulphate as well as the reactions of HNO3 and H2SO4 with mineral dust particles (Metzger et al. 2006), which could account for part of the high spring concentrations.

3.3.3 Particulate acidity

In the literature, different estimations on particulate acidity were found. The most used calculation method is the Molar Ratio (MR) for the measured ions (Eq. 2). Since NH4 +, SO4 2− and NO3 − are the dominant acidifying compounds in the particulate phase, the MR is often simplified for these major inorganic compounds. This simplified ratio is called Neutralisation Ratio (NR) (Eq. 3). Ions are expressed as equivalents.

Recently, Hennigan et al. (2015) evaluated proxy methods to estimate aerosol pH and concluded that the calculation using the MR is not recommendable as it neglects aerosol water as well as partial dissolution of acids and ions on pH; also, there are limitations, resulting from analytical issues. Nevertheless, as these calculations are common in the analysis of particle measurements, this still poses a possibility to compare the ratios at different sites.

For Melpitz, the calculations using the MRs and NRs for the five-year measurement period amount to 0.90 and 0.79, respectively, which implies that the measurement site is predominantly influenced by slightly acidic particles. The lowest cation-to-anion-ratios occurred during autumn and winter. This is probably due to anthropogenic emissions. As for the years 2010 and 2011, the concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ could not be considered due to sampling artifacts. The averaged MR and NR were recalculated for the years 2012 to 2014 and reach 1.0 and 0.82, respectively. A MR of 1.0 is an indicator for neutral conditions. However, the slightly higher NR that is not dependent on both cations still indicates slight acidic conditions for the last three measurement years. Figure 19 shows the calculated NRs and the averaged equivalent concentrations of the sum of NH4 + and Na+ concentration values as well as the sum of Cl−, NO3 − and SO4 2− concentration values for every season from 2010 to 2014. The seasonal variations of the ions, with high concentrations in winter and lower concentrations in summer, are clearly visible. During the measurement period, a decreasing trend for the ions can be observed for Melpitz, which is in agreement with a slightly decreasing particle mass concentration detected by high-volume filter measurements (PM10). However, a clear seasonal dependence of the NR cannot be identified. The NR strongly fluctuates between 0.5 and 1. Acidic particles were dominant in summer of 2011 and winter of 2012. In winter 2012, marine aerosols were significant. The additional calculation of the cation-to-anion ratio with Na+ and Cl− and the other main ions of the NR for the measurement period (in Fig. 19 described as NR with sea salt) lead to an increase in the ratio of approximately 0.1 for nearly all seasons. However, for winter 2012, the increase was around 0.3, indicating a marine influence. The reason for the low peak in summer 2011 remains unclear, although, dust, possibly, could have been an influencing factor. As there are no data for Ca2+, this assumption cannot be verified for this period. After 2012, the ratio increased and then remained the same level, which led to the higher NR in the following three years (on average 0.82). A stronger decrease of NO3 − and SO4 2− in comparison to NH4 + might explain the increase of NR.

Makkonen et al. (2012) observed predominantly acidic particles in winter and basic aerosol in spring due to road dust emissions, resulting in high Ca2+ concentrations, in Finland. Recently, Twigg et al. (2015) investigated particle acidity in Auchencorth Moss in southeast Scotland and found mostly an excess of NH4 +. Closer to Melpitz, Ferm and Hellsten (2012) determined and compared the annual average of NH4 + as well as the anions NO3 − and SO4 2− in Vavihill, situated in Southern Sweden. At this site, the anions dominated over a measurement period of 18 years. These authors demonstrated that high NH4 + concentrations correlate with air-mass transport from the south. Thus, other anthropogenically emitted ions such as SO4 2− and NO3 − could have been transported to Vavihill from Central Europe, resulting in more acidic particles. Squizzato et al. (2013) measured the particulate composition at three sites around Venice, Italy, and subsequently determined the NR. Except for during winter periods, ratios ranged from 0.7 to 0.9. At two sites, the ratio exceeded 1.1, indicating an excess of NH4 +. Measurements during the summer of 2003 in K-puszta, Hungary, showed both fine and coarse mode MRs of 1.25 and 2.87, respectively (Ocskay et al. 2006). The PSCF analysis in chapter 3.3.2 of the present paper indicates high emissions of anthropogenic particulate ions near Hungary that are more acidic. Nevertheless, the particles are strongly basic. Probably, mineral dust particles are the major contributor to the calculated ratio for the coarse mode in K-puszta.

4 Conclusions

Results of concentration measurements for gases and ions in PM10 using MARGA in Melpitz were presented from 2010 to 2014. Besides an evaluation of the instruments, the received data were used to explain diurnal gas concentrations as well as to characterize PM10 with a high time resolution at Melpitz over the whole measurement period.

During this time, different comparisons were executed in order to validate the MARGA system. It was found that some gases are difficult to quantify. A direct comparison to another denuder system without inlet bared great discrepancies for the HNO3 analysis. Its “sticky” behaviour coupled with the influence of the MARGA inlet system results in a strong underestimation. For HONO, the comparison between the denuder and the MARGA shows a slope near unity but a large scatter field with a weak coefficient of determination of 0.41. The difference between both denuder based sampling methods occurs possibly due to different inlet systems, offline analysis for the batch denuder samples and the impact of heterogeneous reactions within the denuders. Also for the MARGA measurements of NH3, possible artifacts should be considered. Similar to HNO3, NH3 has a high potential to adsorb onto the walls. Thus, possible memory effects due to the inlet system could influence the measured concentrations. However, the comparison with different coated denuders showed on average higher concentrations for the MARGA system. The duration time of the gases within the coated denuders was probably too short. However, good correlations of 0.91 and 0.73 and slopes near unity were achieved for the SO2 comparison with a SO2 gas monitor and a Midefix, respectively.

Despite of different cut-off diameters, good agreements were observed for the particulate SO4 2− and NH4 + for the comparisons of MARGA with the ACSM with slopes of 1.39 and 1.20, respectively. Organic nitrates that can be measured by the ACSM could possibly explain the slope of 0.88 for NO3 −. An important advantage of the MARGA is the sampling of the particles free of evaporation artifacts. Accumulated particles in the filter can often interact with ambient gases depending on meteorological conditions. Possible losses due to evaporation of semivolatile particles or positive artifacts due to the adsorption of gases in the filter cannot be excluded for filter measurements. However, the MARGA sampling is also limited by the high time resolution of one hour. The hourly concentrations of Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+ in ambient air are low, as the liquid concentrations of these ions within the MARGA often did not exceed the detection limit and could not be quantified.

Long-term measurements in Melpitz allow us to investigate the variations in time for different compounds. Except for HONO, the gas concentrations peak during daytime. For HCl, photolytic production explains high concentrations in the afternoon and in summertime. The measured noontime peaks of SO2 for all seasons in Melpitz can be explained by transport and down-mixing after the formation of the planetary boundary layer. High concentrations in winter occur due to elevated emissions from domestic heating and an additional enrichment caused by the formation of an inversion layer. NH3 concentrations increase strongly after sunrise. Increasing temperatures lead to an evaporation of both dew droplets in which the gas was dissolved and semi-volatile NH4NO3 in particles that can be transported over a longer range. The well pronounced diurnal cycle of HONO with low concentrations during daytime indicates that despite of a strong photodissociation, additionally, a significant photochemical daytime source exists. Besides, possible heterogeneous reactions within the MARGA denuder could result in an offset of the measured HONO concentrations.

While the gases have mainly local sources, the PSCF analysis and wind data indicate transport processes as the major contributor to the measured particulate concentrations. Thereby, marine and anthropogenic sources could be distinguished. Coarse mode Cl−, Na+ and Mg2+ are the major compounds of sea salt. Both the PSCF analysis and the wind data indicate an origin lying in westerly directions, specifically over the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. However, the major contributions to inorganic PM10 are NO3 −, SO4 2− and NH4 +. The highest concentrations were found in winter at easterly winds. The PSCF analysis calculated the most probable area for anthropogenic emissions over Southern Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia, from where the particulate ions are transported to the Melpitz site. In addition, Cl− and K+ in fine particles also seem to have their origin in this area. They are important indicators of anthropogenic combustion processes.

In order to estimate the acidity of the particles, the MR and NR were calculated. Calculated over the whole measurement period, the MR is 0.9. As the concentrations of Mg2+ and Ca2+ are not available for 2010 and 2011 as a result of analytical artifacts, the MR was calculated for the years 2012 to 2014. With a MR of 1.0, the particles were on average neutral. However, the NR indicates that the sum of NO3 − and SO4 2− seems to decrease faster than NH4 + so that the above mentioned three years were less acidic than the years 2010 and 2011.

References

Acker, K., Febo, A., Trick, S., Perrino, C., Bruno, P., Wiesen, P., Möller, D., Wieprecht, W., Auel, R., Giusto, M., Geyer, A., Platt, U., Allegrini, I.: Nitrous acid in the urban area of Rome. Atmos Environ. 40(17), 3123–3133 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.01.028

Acker, K., Spindler, G., Brüggemann, E.: Nitrous and nitric acid measurements during the INTERCOMP2000 campaign in Melpitz. Atmos Environ. 38(38), 6497–6505 (2004). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.08.030

Allen, H.M., Draper, D.C., Ayres, B.R., Ault, A.P., Bondy, A.L., Takahama, S., Modini, R.L., Baumann, K., Edgerton, E., Knote, C., Laskin, A., Wang, B., Fry, J.L.: Influence of crustal dust and sea spray supermicron particle concentrations and acidity on inorganic NO3 - aerosol during the 2013 Southern oxidant and aerosol study. Atmos Chem Phys. 15(18), 10669–10685 (2015). doi:10.5194/acp-15-10669-2015

Behera, S.N., Betha, R., Balasubramanian, R.: Insights into chemical coupling among acidic gases, ammonia and secondary inorganic aerosols. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 13(4), 1282–U1414 (2013). doi:10.4209/aaqr.2012.11.0328

Berden, G., Peeters, R., Meijer, G.: Cavity ring-down spectroscopy: experimental schemes and applications. Int Rev Phys Chem. 19(4), 565–607 (2000). doi:10.1080/014423500750040627

Canagaratna, M.R., Jayne, J.T., Jimenez, J.L., Allan, J.D., Alfarra, M.R., Zhang, Q., Onasch, T.B., Drewnick, F., Coe, H., Middlebrook, A., Delia, A., Williams, L.R., Trimborn, A.M., Northway, M.J., DeCarlo, P.F., Kolb, C.E., Davidovits, P., Worsnop, D.R.: Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrom Rev. 26(2), 185–222 (2007). doi:10.1002/mas.20115

Carslaw, D.C., Ropkins, K.: openair - An R package for air quality data analysis. Environ Model Softw. 27-28, 52–61 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.09.008

Chen, H.Z., Wu, D., Yu, J.Z.: Comparison of characteristics of aerosol during rainy weather and cold air-dust weather in Guangzhou in late March 2012. Theor Appl Climatol. 124(1–2), 451–459 (2016). doi:10.1007/s00704-015-1424-z

Chow, J.C., Lowenthal, D.H., Chen, L.W.A., Wang, X.L., Watson, J.G.: Mass reconstruction methods for PM2.5: a review. Air Qual Atmos Hlth. 8(3), 243–263 (2015). doi:10.1007/s11869-015-0338-3

Cyrys, J., Gutschmidt, K., Brauer, M., Dumyahn, T., Heinrich, J., Spengler, J.D., Wichmann, H.E.: Determination of acidic sulfate aerosols in urban atmospheres in Erfurt (F.R.G.) and Sokolov (former C.S.S.R.) Atmos Environ. 29(23), 3545–3557 (1995). doi:10.1016/1352-2310(95)00133-J

Dämmgen, U., Thöni, L., Lumpp, R., Gilke, K., Seitler, E., Bullinger, M.: Feldexperiment zum Methodenvergleich von Ammoniak- und Ammonium-Konzentrationsmessungen in der Umgebungsluft 2005 bis 2008 in Braunschweig. vTI Agriculture and Forestry Research - Sonderheft. 337, 62 (2010a)

Dämmgen, U., Thöni, L., Lumpp, R., Gilke, K., Seitler, E., Bullinger, M.: Verfahrenskenngrößen für die Bestimmung von Ammoniakkonzentrationen in der Umgebungsluft - Teil 1: Messungen mit Denudern. Gefahrst Reinhalt L. 5/2010, 197–201 (2010b)

Dasgupta, P.K., Campbell, S.W., Al-Horr, R.S., Ullah, S.M.R., Li, J.Z., Amalfitano, C., Poor, N.D.: Conversion of sea salt aerosol to NaNO3 and the production of HCl: analysis of temporal behavior of aerosol chloride/nitrate and gaseous HCl/HNO3 concentrations with AIM. Atmos Environ. 41(20), 4242–4257 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.09.054

Du, H.H., Kong, L.D., Cheng, T.T., Chen, J.M., Du, J.F., Li, L., Xia, X.G., Leng, C.P., Huang, G.H.: Insights into summertime haze pollution events over Shanghai based on online water-soluble ionic composition of aerosols. Atmos Environ. 45(29), 5131–5137 (2011). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.06.027

Du, H.H., Kong, L.D., Cheng, T.T., Chen, J.M., Yang, X., Zhang, R.Y., Han, Z.W., Yan, Z., Ma, Y.L.: Insights into ammonium particle-to-gas conversion: non-sulfate ammonium coupling with nitrate and chloride. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 10(6), 589–595 (2010). doi:10.4209/aaqr.2010.04.0034

Ellis, R.A., Murphy, J.G., Markovic, M.Z., VandenBoer, T.C., Makar, P.A., Brook, J., Mihele, C.: The influence of gas-particle partitioning and surface-atmosphere exchange on ammonia during BAQS-met. Atmos Chem Phys. 11(1), 133–145 (2011). doi:10.5194/acp-11-133-2011

Fan, J., Yue, X.Y., Jing, Y., Chen, Q., Wang, S.G.: Online monitoring of water-soluble ionic composition of PM10 during early summer over Lanzhou City. J Environ Sci-China. 26(2), 353–361 (2014). doi:10.1016/S1001-0742(13)60431-3

Ferm, M.: Atmospheric ammonia and ammonium transport in Europe and critical loads: a review. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst. 51(1), 5–17 (1998). doi:10.1023/A:1009780030477

Ferm, M., Hellsten, S.: Trends in atmospheric ammonia and particulate ammonium concentrations in Sweden and its causes. Atmos Environ. 61, 30–39 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.07.010

Finlayson-Pitts, B.J., Pitts, J.N.: Atmospheric chemistry: fundamentals and experimental techniques. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York (1986)

Fu, H., Zhang, M., Li, W., Chen, J., Wang, L., Quan, X., Wang, W.: Morphology, composition and mixing state of individual carbonaceous aerosol in urban Shanghai. Atmos Chem Phys. 12(2), 693–707 (2012). doi:10.5194/acp-12-693-2012

Genfa, Z., Slanina, S., Boring, C.B., Jongejan, P.A.C., Dasgupta, P.K.: Continuous wet denuder measurements of atmospheric nitric and nitrous acids during the 1999 Atlanta supersite. Atmos Environ. 37(9–10), 1351–1364 (2003). doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(02)01011-7

Griffith, S.M., Huang, X.H.H., Louie, P.K.K., Yu, J.Z.: Characterizing the thermodynamic and chemical composition factors controlling PM2.5 nitrate: Insights gained from two years of online measurements in Hong Kong. Atmos Environ. 122, 864–875 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.009

Hamed, A., Birmili, W., Joutsensaari, J., Mikkonen, S., Asmi, A., Wehner, B., Spindler, G., Jaatinen, A., Wiedensohler, A., Korhonen, H., Lehtinen, K.E.J., Laaksonen, A.: Changes in the production rate of secondary aerosol particles in Central Europe in view of decreasing SO2 emissions between 1996 and 2006. Atmos Chem Phys. 10(3), 1071–1091 (2010)

Hennigan, C.J., Izumi, J., Sullivan, A.P., Weber, R.J., Nenes, A.: A critical evaluation of proxy methods used to estimate the acidity of atmospheric particles. Atmos Chem Phys. 15(5), 2775–2790 (2015). doi:10.5194/acp-15-2775-2015

Henschel, S., Querol, X., Atkinson, R., Pandolfi, M., Zeka, A., Le Tertre, A., Analitis, A., Katsouyanni, K., Chanel, O., Pascal, M., Bouland, C., Haluzai, D., Medina, S., Goodman, P.G.: Ambient air SO2 patterns in 6 European cities. Atmos Environ. 79, 236–247 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.06.008

Herrmann, H.: Kinetics of aqueous phase reactions relevant for atmospheric chemistry. Chem Rev. 103(12), 4691–4716 (2003). doi:10.1021/cr020658q

Herrmann, H., Brüggemann, E., Franck, U., Gnauk, T., Löschau, G., Müller, K., Plewka, A., Spindler, G.: A source study of PM in saxony by size-segregated characterisation. J Atmos Chem. 55(2), 103–130 (2006). doi:10.1007/s10874-006-9029-7

Hesterberg, R., Blatter, A., Fahrni, M., Rosset, M., Neftel, A., Eugster, W., Wanner, H.: Deposition of nitrogen-containing compounds to an extensively managed grassland in central Switzerland. Environ Pollut. 91(1), 21–34 (1996). doi:10.1016/0269-7491(95)00036-Q

Hopke, P.K.: Review of receptor modeling methods for source apportionment. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 66(3), 237–259 (2016). doi:10.1080/10962247.2016.1140693

Hsu, Y.M., Clair, T.A.: Measurement of fine particulate matter water-soluble inorganic species and precursor gases in the Alberta Oil Sands region using an improved semicontinuous monitor. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 65(4), 423–435 (2015). doi:10.1080/10962247.2014.1001088

Huang, X.H.H., Bian, Q., Ng, W.M., Louie, P.K.K., Yu, J.Z.: Characterization of PM2.5 major components and source investigation in suburban Hong Kong: A one year monitoring study. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 14, 237–250 (2014)

Huang, Y., Li, L., Li, J., Wang, X., Chen, H., Chen, J., Yang, X., Gross, D.S., Wang, H., Qiao, L., Chen, C.: A case study of the highly time-resolved evolution of aerosol chemical and optical properties in urban Shanghai. China Atmos Chem Phys. 13(8), 3931–3944 (2013). doi:10.5194/acp-13-3931-2013

Jansen, R.C., Chen, J.M., Hu, Y.J.: The impact of nonlocal ammonia on submicron particulate matter and visibility degradation in urban Shanghai. Adv Meteorol. (2014a). doi:10.1155/2014/534675

Jansen, R.C., Shi, Y., Chen, J.M., Hu, Y.J., Xu, C., Hong, S.M., Li, J., Zhang, M.: Using hourly measurements to explore the role of secondary inorganic aerosol in PM2.5 during haze and fog in Hangzhou, China. Adv Atmos Sci. 31(6), 1427–1434 (2014b). doi:10.1007/s00376-014-4042-2

Jones, A.M., Harrison, R.M.: Temporal trends in sulphate concentrations at European sites and relationships to sulphur dioxide. Atmos Environ. 45(4), 873–882 (2011). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.11.020

Katzman, T.L., Rutter, A.P., Schauer, J.J., Lough, G.C., Kolb, C.J., Van Klooster, S.: PM2.5 and PM10–2.5 compositions during wintertime episodes of elevated PM concentrations across the midwestern USA. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 10(2), 140–U113 (2010). doi:10.4209/aaqr.2009.10.0063

Keck, L., Wittmaack, K.: Effect of filter type and temperature on volatilisation losses from ammonium salts in aerosol matter. Atmos Environ. 39(22), 4093–4100 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.03.029

Keuken, M.P., Schoonebeek, C.A.M., Vanwensveenlouter, A., Slanina, J.: Simultaneous sampling of NH3, HNO3, HCl, SO2 and H2O2 in ambient air by a wet annular denuder system. Atmos Environ. 22(11), 2541–2548 (1988). doi:10.1016/0004-6981(88)90486-6

Khezri, B., Mo, H., Yan, Z., Chong, S.L., Heng, A.K., Webster, R.D.: Simultaneous online monitoring of inorganic compounds in aerosols and gases in an industrialized area. Atmos Environ. 80, 352–360 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.08.008

Khlystov, A., Wyers, G.P., Slanina, J.: The steam-jet aerosol collector. Atmos Environ. 29(17), 2229–2234 (1995). doi:10.1016/1352-2310(95)00180-7

Kleffmann, J., Wiesen, P.: Technical note: quantification of interferences of wet chemical HONO LOPAP measurements under simulated polar conditions. Atmos Chem Phys. 8(22), 6813–6822 (2008)