Abstract

The minimum wage is an important determinant of earnings among lower-skilled parents and may have implications for their children’s living arrangements. We used nationally representative data to examine associations between the minimum wage and fathers’ residence with their biological children. Results revealed no association between the minimum wage and father residence among all low-income families. However, this finding masks important heterogeneity within these families based on which parent’s earnings were sensitive to minimum wage levels. In families where only fathers’ earnings were sensitive to minimum wage levels, fathers were more likely to live with their children as minimum wages increased, consistent with research that shows the importance of economic stability for fathers’ residence and custody arrangements. In contrast, in families where only mothers’ earnings were sensitive to minimum wage levels, higher minimum wages were negatively associated with fathers’ residence, consistent with theories of maternal independence. These associations with residence were not observed in situations where both parents’ earnings were sensitive to the minimum wage. Results indicate that these economic policies may be consequential for family processes and well-being in key subsets of low-earning families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These pathways are not exhaustive, and we acknowledge the possibility that there may be other ways in which the minimum wage might affect men’s residence that we could not capture with our data.

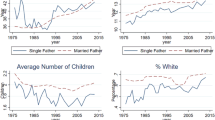

As a nationally representative survey, the ASEC includes most types of family and non-family households. Our sample included the following family types: married biological mothers and fathers, cohabiting (unmarried) biological mothers and fathers, biological mothers with married or cohabiting partners without shared biological children (stepfathers), biological fathers with married or cohabiting partners without shared biological children (stepmothers), single biological mothers, and single biological fathers. While many children do not live with a biological parent, this population is more difficult to identify accurately and consistently in the CPS and was thus excluded from the present analysis.

The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study (FFCWS) was established in part to explicitly address this problem by both interviewing nonresident fathers and collecting detailed information about nonresident parents from the resident parent. While FFCWS has been provided valuable insights on families by incorporating nonresident fathers, it lacks the generalizability, sample sizes, periodicity, and representation across states that were necessary to identify the effects of state policy changes in our study.

Parents were considered unemployed if they were participants in the labor force but not currently working. Labor force participation was defined as having worked in the prior year or reporting not being able to find work as the reason for not working in the prior year.

Findings were robust to alternative definitions of parents with wages up to 1.5 times the minimum wage using earnings alone or only the first criterion of earnings and employment. Findings were not robust to using education levels as a proxy for minimum wage earnings, however. Supplemental analyses (available on request) indicated that that higher minimum wages were not associated with parental earnings when using education levels as a proxy for wages, but were associated with higher earnings when using any earnings-based definition in a way consistent with findings presented in Table 4. Our findings are thus only generalizable to families in which parental earnings rise as minimum wage levels increase, but not to all low socioeconomic status families defined using education or skill level. The implications of this limitation are addressed in detail in the discussion.

For example, MMW families could take any of the following forms: 1) coresident biological parents in which the biological father is not sensitive to the minimum wage because he is either out of the labor market or has higher earnings; or 2) mothers living apart from their child’s biological father who is not sensitive to the minimum wage. This second group of mothers could be single mothers living with a partner with whom they do not share children, or living with other relatives or roommates.

This simple classification obscures some nuances of multi-partner fertility, as parents may live with some biological children but not others or live with both biological and step children. Thus, a two-biological parent household could include various types of complex family structures as long as a couple has at least one shared biological child in the household. For example, these households could include fathers who live with one biological child but apart from another, or step-children living apart from their own biological fathers but with the biological father of a younger half-sibling. Our approach prioritized parents’ current relationships, rather than the experiences of children or relationship trajectories, consistent with our theoretical conceptualization of how the minimum wage could impact family structure. On the other hand, this approach could have masked heterogeneity in family dynamics.

References

Addo, F. R. (2014). Debt, cohabitation, and marriage in young adulthood. Demography, 51(5), 1677–1701.

Agan, A. Y., & Makowsky, M. D. (2018). The minimum wage, EITC, and criminal recidivism. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Allegretto, S. A., Dube, A., & Reich, M. (2011). Do minimum wages really reduce teen employment? Accounting for heterogeneity and selectivity in state panel data. Industrial Relations, 50(2), 205–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2011.00634.x.

Allegretto, S. A., Dube, A., Reich, M., & Zipperer, B. (2013). Credible research designs for minimum wage studies (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2336435). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2336435. Accessed 6 July 2017.

Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data (Vol. 136). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Autor, D. H., Manning, A., & Smith, C. L. (2016). The contribution of the minimum wage to us wage inequality over three decades: A reassessment. American Economic Journal, 8(1), 58–99. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20140073.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Belman, D., Wolfson, P., & Nawakitphaitoon, K. (2015). Who Is affected by the minimum wage? Industrial Relations, 54(4), 582–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12107.

Bernstein, J., & Shierholz, H. (2014). The minimum wage: A crucial labor standard that is well targeted to low- and moderate-income households. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(4), 1036–1043. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21791.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., & Waldfogel, J. (2000). Understanding young women’s marriage decisions: The role of labor and marriage market conditions. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 53(4), 624–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2696140.

Bradley, D. H. (2018). State minimum wages: an overview (CRS Report No. R43792).

Bzostek, S. H., McLanahan, S. S., & Carlson, M. J. (2012). Mothers’ repartnering after a nonmarital birth. Social Forces, 90(3), 817–841. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos005.

Cancian, M., & Meyer, D. R. (1998). Who gets custody? Demography, 35(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/3004048.

Cancian, M., Meyer, D. R., Brown, P. R., & Cook, S. T. (2014). Who gets custody now? Dramatic changes in children’s living arrangements after divorce. Demography, 51(4), 1381–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0307-8.

Card, D., & Krueger, A. B. (1994). Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The American Economic Review, 84(4), 772–793.

Carlson, M. J., & Berger, L. M. (2013). What kids get from parents: Packages of parental involvement across complex family forms. Social Service Review, 87(2), 213–249.

Carlson, M. J., McLanahan, S., & England, P. (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41(2), 237–261.

Carlson, M. J., VanOrman, A. G., & Turner, K. J. (2017). Fathers’ investments of money and time across residential contexts. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12324.

Cherlin, A. J. (2014). Labor’s love lost: The rise and fall of the working-class family in America. Russell Sage Foundation. Accessed 20 September 2017

Cherlin, A. J., Hurt, T. R., Burton, L. M., & Purvin, D. M. (2004). The influence of physical and sexual abuse on marriage and cohabitation. American Sociological Review, 69(6), 768–789.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x.

Cooper, D., & Hall, D. (2013). Raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 would give working families, and the overall economy, a much-needed boost (EPI Briefing Paper No. 357). Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/files/2013/IB354-Minimum-wage.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2017

DeFina, R. H. (2008). The impact of state minimum wages on child poverty in female-headed families. Journal of Poverty, 12(2), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875540801973542.

DeNavas-Walt, C., & Proctor, B. D. (2015). Income and poverty in the United States: 2013, P60-249. Current Population Reports. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf. Accessed.

Dube, A. (2018). Minimum wages and the distribution of family incomes (No. w25240) (p. w25240). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25240

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2011). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. California: Univ of California Press.

Edin, K., & Lein, L. (1997). Making ends meet: How single mothers survive welfare and low-wage work. Thousand Oaks: Russell Sage Foundation.

Edin, K., Nelson, T. J., Cherlin, A. J., & Francis, R. (2019). The Tenuous attachments of working-class men. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 211–228.

Flood, S., King, M., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J. R. (2017). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 4.0. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2003). Marriage: A luxury good? Zero to Three, 23(3), 13–17.

Garfinkel, I., McLanahan, S. S., Meyer, D. R., & Seltzer, J. (1998). Fathers under fire. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2006). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gibson-Davis, C. M. (2009). Money, marriage, and children: Testing the financial expectations and family formation theory. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 146–160.

Hamer, J., & Marchioro, K. (2002). Becoming custodial dads: Exploring parenting among low-income and working-class African American fathers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(1), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00116.x.

Herbst, C. M. (2011). The impact of the earned income tax credit on marriage and divorce: Evidence from flow data. Population Research and Policy Review, 30(1), 101–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-010-9180-3.

Hirsch, B., Macpherson, D. A., & Vroman, W. G. (2001). Estimates of union density by state. Monthly Labor Review, 124(7), 51–55.

Jardim, E., Long, M. C., Plotnick, R., van Inwegen, E., Vigdor, J., & Wething, H. (2017). Minimum wage increases, wages, and low-wage employment: evidence from Seattle (Working Paper No. 23532). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23532

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663.

Kim, T., & Taylor, L. J. (1995). The employment effect in retail trade of California’s 1988 minimum wage increase. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 13(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.2307/1392371.

Komro, K. A., Livingston, M. D., Markowitz, S., & Wagenaar, A. C. (2016). The effect of an increased minimum wage on infant mortality and birth weight. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1514–1516. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303268.

Laroque, G., & Salanié, B. (2002). Labour market institutions and employment in France. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 17(1), 25–48.

Lichter, D. T., Sassler, S., & Turner, R. N. (2014). Cohabitation, post-conception unions, and the rise in nonmarital fertility. Social Science Research, 47, 134–147.

Livingston, G. (2013). The Rise of Single Fathers. Pew Research Center’s social & demographic trends project. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/07/02/the-rise-of-single-fathers/. Accessed 10 April 2018.

McLanahan, S., & Beck, A. N. (2010). Parental relationships in fragile families. The Future of children/Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, 20(2), 17.

McLanahan, S., Tach, L., & Schneider, D. (2013). The Causal effects of father absence. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 399–427. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704.

Meyer, D. R., & Cancian, M. (2012). “I’m not supporting his kids”: Nonresident Fathers’ contributions given mothers’ new fertility. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 132–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00880.x.

Mincy, R. B. (2006). Black males left behind. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Mincy, R. B., & De la Cruz Toledo, E. (2016). Nonresident father involvement. Children of the Great Recession, 621, 149–177.

Mincy, R. B., Miller, D. P., & De la Cruz Toledo, E. (2016). Child support compliance during economic downturns. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.018.

Mishel, L. (2013). Declining value of the federal minimum wage is a major factor driving inequality (Issue Brief No. 351). Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/declining-federal-minimum-wage-inequality/.

Morgan, D. R., & Kickham, K. (2001). Children in poverty: Do state policies matter? Social Science Quarterly, 82(3), 478–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/0038-4941.00037.

NBER. (2016). Current population survey 2016 annual social and economic (ASEC) supplement. https://www.nber.org/cps/cpsmar2016.pdf. Accessed 27 October 2017.

Nepomnyaschy, L., & Garfinkel, I. (2011). Fathers’ involvement with their Nonresident children and material hardship. Social Service Review, 85(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1086/658394.

Neumark, D., Schweitzer, M., & Wascher, W. (2000). The effects of minimum wages throughout the wag distribution. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper (7519). https://www.nber.org/papers/w7519.pdf. Accessed 5 October 2017.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. (1997). Do minimum wages fight poverty? (Working Paper No. 6127). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w6127.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. (2000). Using the EITC to help poor families: New evidence and a comparison with the minimum wage. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w7599. Accessed 16 October 2017.

Neumark, D., & Wascher, W. (2006). Minimum wages and employment: A review of evidence from the new minimum wage research (Working Paper No. 12663). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w12663.

New York State. (2016). New York State’s minimum wage. Welcome to the State of New York. https://www.ny.gov/new-york-states-minimum-wage/new-york-states-minimum-wage. Accessed 21 June 2018.

OECD. (2013). Minimum wages relative to median wages. https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00313-en. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/data/data-00313-en.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1997). Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: The specialization and trading model. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 431–453.

Osborne, C., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1345–1366.

Pettit, B. (2012). Invisible men: Mass incarceration and the myth of black progress. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Raissian, K. M., & Bullinger, L. R. (2017). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.033.

Romich, J., & Hill, H. D. (2018). Coupling a federal minimum wage hike with public investments to make work pay and reduce poverty. RSF, 4(3), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2018.4.3.02.

Ross, H. L., Sawhill, I. V., & MacIntosh, A. R. (1975). Time of transition: The growth of families headed by women. The Urban Institute. Accessed 20 September 2017

Rubin, D. B. (2004). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Sabia, J. J. (2008). Minimum wages and the economic well-being of single mothers. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 27(4), 848–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20379.

Sabia, J. J., & Burkhauser, R. V. (2010). Minimum wages and poverty: Will a $9.50 federal minimum wage really help the working poor? Southern Economic Journal, 76(3), 592–623.

Sassler, S., & Miller, A. J. (2011). Class differences in cohabitation processes. Family Relations, 60(2), 163–177.

Sayer, L. C., & Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Women’s economic independence and the probability of divorce: A review and reexamination. Journal of Family Issues, 21(7), 906–943.

Shenhav, N. (2018). Lowering standards to wed? Spouse quality, marriage, and labor market responses to the gender wage gap. Working Paper, Dartmouth College.

Sinkewicz, M., & Garfinkel, I. (2009). Unwed fathers’ ability to pay child support: New estimates accounting for multiple-partner fertility. Demography, 46(2), 247–263.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Porter, M. (2005). “Everything’s there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 680–696.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67(1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088937.

Tach, L., Mincy, R. B., & Edin, K. (2010). Parenting as a “Package Deal”: Relationships, fertility, and nonresident father involvement among unmarried parents. Demography, 47(1), 181–204.

Totty, E. (2017). The effect of minimum wages on employment: A factor model approach. Economic Inquiry, 55(4), 1712–1737. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12472.

Tsao, T.-Y., Konty, K. J., Van Wye, G., Barbot, O., Hadler, J. L., Linos, N., et al. (2016). Estimating potential reductions in premature mortality in New York City from raising the minimum wage to $15. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1036–1041. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303188.

United States Department of Labor. (2017). Consolidated state minimum wage table. https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/america.htm#Consolidatedwagetoc. Accessed 27 October 2017.

University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research. (2017). UKCPR national welfare data, 1980–2016. Lexington KY: Gatton College of Business and Economics, University of Kentucky. https://www.ukcpr.org/data.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015). Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2015 : BLS Reports. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2015/home.htm. Accessed 3 August 2017.

US Census Bureau. (2006). Design and methodology: current population survey, (Technical Paper 66), 175.

US Census Bureau. (2018a). America’s families and living arrangements: 2017. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/families/cps-2017.html. Accessed 22 June 2018.

US Census Bureau. (2018b). Women 15 To 50 years who had a birth in the past 12 months by marital status and poverty status in the past 12 months: 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/16_5YR/B13010/0100000US.

Waller, M. R. (2002). My baby’s father: Unmarried parents and paternal responsibility. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Waller, M. R. (2009). Family man in the other America: New opportunities, motivations, and supports for paternal caregiving. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 624(1), 156–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716209334372.

Waller, M. R., & Peters, H. E. (2008). The risk of divorce as a barrier to marriage among parents of young children. Social Science Research, 37(4), 1188–1199.

Waller, M. R., & Swisher, R. (2006). Fathers’ risk factors in fragile families: Implications for “Healthy” relationships and father involvement. Social Problems, 53(3), 392–420. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2006.53.3.392.

Watson, T., & McLanahan, S. (2011). Marriage Meets the Joneses Relative Income, Identity, and Marital Status. Journal of human resources, 46(3), 482–517.

Western, B., & Rosenfeld, J. (2011). Unions, norms, and the rise in U.S. wage inequality. American Sociological Review, 76(4), 513–537.

Western, B., & Wildeman, C. (2009). The black family and mass incarceration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621(1), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208324850.

Wilson, W. J. (1997). When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor (1st ed.). Random House: New York.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the early feedback of James Ziliak and Robert Plotnick provided at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management conference.

Funding

This research was supported by generous funding from the William T. Grant Foundation, the content is solely the responsibility of the and does not necessarily represent the official views of our funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

The authors did not collect data from human participants for this research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dwyer Emory, A., Miller, D.P., Nepomnyaschy, L. et al. The Minimum Wage and Fathers’ Residence with Children. J Fam Econ Iss 41, 472–491 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09691-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09691-y