Abstract

In the analysis of archaeological relationships and processes, a uniform classification of the dataset is a fundamental requirement. To achieve this, a standardised taxonomic system, as well as consistent and valid criteria for the grouping of sites and assemblages, must be used. The Central European Late Palaeolithic (ca. 12,000–9700 cal BC) has a long research history and many regionally and temporally specific units—groups and cultures—are recognised. In this paper, we examine the complex taxonomic landscape of this period and critically analyse the use of typological, functional and economic criteria in the definition of selected groups. We subject three different archaeological taxonomic units, the Bromme culture from Denmark, the Fürstein group from Switzerland and the Atzenhof group from Germany, to particularly detailed scrutiny and highlight that the classificatory criteria used in their definition are inconsistent across units and most likely unsuitable for circumscribing past sociocultural units. We suggest a comprehensive re-examination of the overarching taxonomic system for the Late Palaeolithic, as well as a re-evaluation of the methodologies used to delineate sociocultural units in the Palaeolithic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unravelling past spatio-temporal patterns and processes of culture change is one of the primary aims of archaeology. A fundamental precondition for recognising such processes is the unambiguous definition of the analytical taxonomic units used for investigation (see Gamble et al. 2005: Box 1). This entails (1) consistent criteria for their definition and delimitation, the validity of which is established a priori in relation to the questions asked, (2) a clear taxonomic system into which such archaeological entities can be placed and (3) agreement on the meaning of the relative ranks within this taxonomic system and their prehistoric reality. These three requirements are essential for conducting comparative and cumulative research at a supraregional and diachronic scale.

The definition of taxonomic units was of great concern to early practitioners, and the typological method (Montelius 1903) was developed, with inspiration from similar taxonomic efforts in biology, to this end (Riede 2006). Also in Palaeolithic archaeology, taxonomic units—cultures, groups, industries and traditions—proliferated and were often seen to represent actual past ethnic groups (Bergsvik 2003; Clark 1994; Sackett 1991). For the Middle Palaeolithic of Europe, the infamous debate between Binford, Bordes and Mellars in the 1960s largely broke with the tradition of casting such archaeological phenomena as ethnic entities, but a legacy of taxonomic inconsistency still haunts this period (Bisson 2000; Clark 1999, 2009; Clark and Riel-Salvatore 2006; Shea 2014). A similarly soul-searching debate rocked the research community of the Epipalaeolithic in the Levant in the 1990s, pitching those who saw variation in the archaeological record as reflecting ethnic units (Fellner 1995; Goring-Morris 1996; Kaufman 1995; Phillips 1996) against those who were deeply sceptical of such attributions for primarily epistemological reasons (Clark 1996) and preferred explanations rooted in behavioural ecological theory (Neeley and Barton 1994; Barton and Neeley 1996). The Central European Late Palaeolithic (ca. 12,000–9700 cal BC) is another example of an archaeological taxonomic landscape that has a long patchwork research history and is hence characterised by a great deal of taxonomic heterogeneity. Otte and Keeley (1990: 577) noted, for instance, that taxonomic units in this period are usually derived from the early excavations of key sites—reflected aptly in the common practice of naming cultures or groups after these—and that the “explanations offered for the events in such sequences, whether explicit or implicit, tend to focus on local phenomena or events and reinforce ideas of local continuity and evolution”. An even more explicit critique has been voiced by Houtsma et al. (1996: 143) who argue specifically for northern Europe that “[o]nly when researchers of the Late Palaeolithic habitation of the Northwest European Plain escape the constraints of contemporary national borders and the paradigmatic straight-jackets of provincialism and regional chauvinism, which lead to insularity, will we be in a position to gain analytical control of the totality of extant data partitioned into uniform and mutually comparable sets of demonstrably relevant attributes”. Whilst we are uncertain about the tone of these critiques, we appreciate their sentiment. Approaching the issue empirically, we here review and critically analyse a selected sample of Late Palaeolithic taxonomic units proposed for the Central European Late Palaeolithic. We scrutinise these for how they are constructed and their spatial and temporal boundaries and how these articulate with ethnographic data on hunter-gatherer territorial sizes and the marking of these via lithic artefacts.

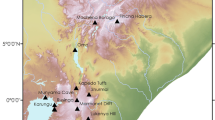

At present, a minimum of 23 different Late Palaeolithic cultures, subcultures and groups—here italicised when referred to as a formal taxonomic unit—are defined in the area framed approximately by the Alps in the south, the Baltic and North Sea in the north, the River Bug in the east and the River Meuse in the west (Fig. 1). These units are commonly ascribed to either the arch-backed point technocomplex or the tanged point technocomplex (Valde-Nowak et al.2012), but the fact that many of the same sites were used to define both of these macrolevel taxonomic units by emphasising different usually typological components already hints at classificatory inconsistency (see Schwabedissen 1954; Taute 1968). This is aggravated at lower taxonomic levels where non-uniform taxonomic systems, bespoke terminologies and variable criteria as well as their inconsistent application obscure the nature of the proposed groups and the possible relationships among them. We explore the likely triggers for this complex situation. The extant units may be the expression of locally, regionally or nationally flavoured notions of prehistoric ethnic identities, linguistic divides and differing research traditions and paradigms (Binford 1964; Clark 1994: 315; Riede 2017). To investigate the various inconsistencies in the present taxonomic landscape, different maps of site and tool distributions will be used as major analytical tools. Alongside research historical issues, further problems are associated with the criteria used to circumscribe what often is supposed to be the representation of past sociocultural reality (Clark 1988: 4; Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1979: 16; Brinch Petersen 2009; Vasil’ev 2001: 4). Using the Bromme culture as an example of the application of typological criteria, the Fürstein group as a representation of tool frequency-based delimitations and the Atzenhof group as a raw material-based subculture, we demonstrate that such cultural-taxonomic definitions and their sociocultural value should be treated with caution.

The proposed regionalisation that is underwritten by this taxonomic landscape is fully in line with an entrenched understanding of this period as a prelude to the early Holocene, which arguably did see the development of more regionally circumscribed Mesolithic entities (see Bailey and Spikins 2008). Our results summarily indicate, however, that this supposed regional patterning is the complex result of research historical processes and biases combined with a lack of rigour in constructing archaeological taxonomic units. Thus, interpretations of Late Palaeolithic migrations, adaptations and identities stand on uncertain ground.

The Historical Development of Late Palaeolithic Taxonomies

The formation of today’s Late Palaeolithic taxonomic landscape in the study area began in the early twentieth century when a large tanged point and reindeer antler were discovered in association with geological evidence for their ice age date at Nørre Lyngby in the very north of Denmark (Jessen and Nordmann 1915). Similar finds became known from the wider region and Ekholm (1925) quickly codified these into the Lyngby culture. At this point, the Azilian was already established as a Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene culture found in south-western Europe (Piette 1895). Clark proposed a general absence of Azilian elements in Central and Northern Europe in his major 1936 synthesis, but Krukowski (1939) shortly thereafter defined another important and long-lived taxonomic unit of the Late Palaeolithic that was thought of as closely allied with the Azilian: He described the Eastern European Tarnowian primarily based on characteristic end-scraper types and frequencies (Krukowski 1939; Schild 1960, 1975) as opposed to the Western European Azilian where the presence of arch-backed points was thought to be essential.

These early characterisations were followed by three busy decades of defining local entities in various parts of Central Europe with the aim of mapping the presence, origin and diffusion of regionally distinct sociocultural units: The necessary definition of actors that could partake in the contemporaneous ‘ethnogeography’ that was being mapped (Eriksen 2000) and dynamic ‘palaeohistory’ (Kozlowski and Kozlowski 1979) that was being written (Fig. 2). Well-known among these are the Federmessergruppen (Schwabedissen 1954), the Stielspitzengruppen (TPT) (Taute 1968) and the Bromme culture (Mathiassen 1946), which was, for Taute, part of his TPT complex but which is to date most commonly seen as a stand-alone culture. All of these taxonomic groups are thought to be associated with specific typological characteristics and type fossil artefacts, namely arch-backed forms, small tanged points and large tanged points, respectively. Whilst efforts were also made to remove some of this terminological profusion—Brinch Petersen (1970), for instance argued for a collapse of the Lyngby and Bromme cultures—a plethora of lower level taxonomic units were put forward in the wake of both the Federmessergruppen and the Stielspitzengruppen (Table 1). These units, as well as others (Chmielewska 1961; Chmielewski 1961; Sawicki 1933; Schwantes 1939; Sinitsyna 2002; Szymczak 1987, 1999), were believed to have their territories in the lowlands of Belgium, the Netherlands, northern Germany, Poland and further to the east (Fig. 3). Difficulties abound, however, owing to the ambiguous definition of key artefact classes and their evident co-occurrence at many sites within and outside the traditional core ‘territories’ of these groups. For instance, different large tanged point variants are imprecisely distinguished from each other and from smaller variants (Fischer 1985; Serwatka and Riede 2016), and they commonly occur as minor but integral elements within arch-backed point (Federmessergruppen) assemblages in Northern Europe (Breest and Gerken 2008; Kobusiewicz 2009a, b; Riede 2017; Riede et al.2011).

Two exemplary maps for the suggested taxonomic variability and its spatial signature in the Late Palaeolithic, and the ways in which these units moved about, from Kozlowski and Kozlowski (1979).a Europe in the tenth millennium BC (F = Federmesser); b Europe in the ninth to eighth millennia BC

A somewhat different scenario unfolded in the southern part of Central Europe, specifically Switzerland (Fürstein group; see Nielsen 2002, 2009; Wyss 1953, 1968), southern Germany (Atzenhof group; see Naber 1974; Schönweiß 1974, 1992) and the Czech Republic (Ostroměr group; see Burdukiewicz 1999; Vencl 1966, 1970a, b), where the naming of new subcultures of the arch-backed point complex was less common and therefore resulted in fewer units and little overlap in terms of geographic range or shared key sites. In addition, the defining characteristics were either tool frequencies or raw material procurement patterns, both of which were invested with quasi-ethnic value. In notable contrast, assemblages in areas such as the Rhineland or the Danube Basin were never assigned to regional groups, industries or subcultures.

In the description of these supposed regional developments, their proponents have used taxonomies and terminologies that differ in subtle but important ways (Table 2). Uncertain about the various units’ rank within the overarching system and cognisant of the taxonomic challenge at hand, Schwabedissen (1954) suggested the term of the Gruppe (group) to be used as a preliminary category, which could be re-arranged and reclassified if and when the respective unit’s relative position is clarified by further research. Only too aware of the need to work with the often poorly or not at all stratified material in northern Europe (Schwabedissen 1955), he rather problematically suggested that a minimum of only two sites with comparable characteristics would be sufficient to circumscribe a group. Taute’s (1968) classification approach was similar, but his focus on another type fossil artefact, tanged points, as the dominant taxonomic index led him to reclassify—or rather parallel classify—many of the same locales into different groups, as well as to taxonomically demote the Bromme culture into a group (the Segebro-Bromme group) as a sub-unit of his wider tanged point complex. In addition, he expanded the taxonomic system by the German term Industrie, which would describe single sites with outstanding properties, albeit without paradigmatically qualifying the specific properties of such exceptional assemblages. Taute’s terminology is not to be confused with the French term Industrie promoted by Schild (1965), which taxonomically is more akin to Schwabedissen’s Gruppe.

The comprehensive classification exercises of Schwabedissen, Taute and Kozlowski and Kozlowski were major contributions to systematically understanding the archaeology of the Late Palaeolithic in the wider region. Each approach also displays a great deal of internal consistency when it comes to their classificatory logic. However, with regard to the articulation between these and specifically with regard to many stand-alone taxonomic units proposed subsequently, such as the Atzenhof group, no explicit translation key has ever been provided, leaving a given group’s intended taxonomic rank and sociocultural connotations unclear. A problem common to all taxonomies presented above is the lack of clearly defined and externally validated criteria as well as (where relevant) statistical thresholds for describing commonalities and differences. Yet, once in place, many taxonomic units proposed for Late Palaeolithic in Europe have become reified when they are used in geographically more wide-ranging syntheses that by necessity gloss over the often difficult to obtain source-critical acumen. Obscurity in the initial definition, language barriers and Houtsma and colleagues’ (probably largely implicit) “paradigmatic straight-jackets of provincialism” have all contributed to the present taxonomic patchwork. In the following, we focus on the latter two biases in an effort to articulate the development of these taxonomies with wider political and scientific trends.

Triggers of Regionalism

Archaeology is “the place where present and past meet and interact” (Kane 2003: 1) with the clear implication that all archaeological work and interpretations are related to political leanings of the individual archaeologist (Tilley 1998). There are numerous prominent cases of national or even nationalistic agendas influencing archaeological research (see Kane 2003; Kohl 2012). Such ‘invented traditions’ (Hobsbawn 1983) were used most prominently by the Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe in the Third Reich to naturalise and hence legitimise the ruling party’s racial ideology (Koop 2012), but also in Great Britain to connect the modern population of the British mainland with the Celts and illustrate continuity (Samida 2013: 355f). On a regional level, such as in Saxony, prehistory is used strategically to foster spatially circumscribed identities (Sommer 2000). Commonly, national, regional and local perspectives on the past are institutionalised in museums at attendant scales whose raison d’être is often intimately linked with that very geography.

With regard to the Palaeolithic, such influences are usually subtler, yet far from absent (Tomášková 2003). The latter half of the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth century were characterised by substantial rivalry between nation states and alliances thereof, the influence of which on, for instance, the taxonomy of the Upper Palaeolithic has been noted (Felgenhauer 1996). Similarly, Riede (2017) traces the subtle effects of recent political history, amateur involvement and codification through reified national registration practices on the status of the Bromme culture in southern Scandinavia. In Denmark, the use of the past is a common feature in business advertisement and political discourse and serves to negotiate the position of a once powerful nation in the recent and contemporary political landscape (Dobat 2013; Høgh 2008; Kristiansen 1993). More recently, nationalism had been replaced in favour of a certain Europeanism that evokes a distant European past, transnational networks and early forms of globalisation (Samida 2013: 356; Sommer 2000: 128), a trend that in concert with theoretical re-orientations in archaeology away from descriptive culture history towards largely functional studies (Trigger 1989) may have led to the waning of taxonomic inventiveness (Fig. 4).

At present, the attitude of emphasising overall homogeneity in the Late Palaeolithic (e.g. De Bie and Vermeersch 1998) coexists with approaches that instead stress supposedly regionally circumscribed heterogeneity. The latter can perhaps best be described by the German term ‘Heimatkunde’, which privileges the affection for and knowledge of local landscapes, history and prehistory in relation to wider geographic scales. This ‘Heimatkunde’ approach is epitomised by the Atzenhof group, found more or less exclusively in the region of Franconia. Locals are keen to insist on their ‘recent’ incorporation of Franconia into Bavaria in 1803, which among other initiatives, has resulted in the celebration of the Day of the Franconians (Tag der Franken) in 2006 and onwards (Kluxen and Hecht 2010). Although no explicit reference is made to the Palaeolithic here, such events evoke notions of (lost) regional independence and (supposed) linguistic and cultural difference. The local focus encapsulated by the Atzenhof group is also clearly reflected in the publication practice regarding sites in this region. Typically, small and locally distributed publications, like the Oberpfälzer Heimat (Schönweiß 1997) or the Archiv für Geschichte von Oberfranken (Schönweiß 1993; Schönweiß and Sticht 1968) or publications printed at the author’s cost (e.g. Vorgeschichtliche Funde aus dem Landkreis Schwandorf—see Süß and Thomann 2009), are used to present new findings. For researchers from outside the region or from even further afield, these publications are often difficult to obtain, sometimes arduous to read, and their scientific status hard to ascertain.

Another important and prosaic bias at play may be found in the logistics of research. The proponents of the various Late Palaeolithic taxonomic units are typically closely linked to or based in the region that also make up the core of ‘their’ culture, group or industry. It was only Friedrich Naber from the University of Bonn, who worked outside his institution’s ‘claim’, and Wolfgang Taute, whose research transgressed the border to Poland. All other key researchers were stationed within the confines of ‘their’ unit (compare Fig. 2 and Fig. 5). Ease of access to original material versus drawings or photographs, respectively, coupled with inherently local perspectives may have exaggerated differences rather than commonalities between regions.

Areas of Slavic, Uralic and Germanic languages in comparison to the different axonomic units defined in the study area; the units are set to 25% opacity, areas of strong overlay are represented by darker colouring; Red dots designate workplaces of the authors defining local units; the southern part of the study area contains relatively few such taxonomic units units, although an extensive cover of ABP sites is known in this region (e.g. Rhineland; Projection: UTM32N; EPSG: 7416; Data: GADM, Natural Earth Data)

Another prominent, albeit rarely articulated, obstacle to supraregional comparisons is language. Publications on the Late Palaeolithic in Eastern Europe—but also to a lesser degree in Germany (see above) or Scandinavia with regard to the Late Palaeolithic (Eriksen 1999)—are often still published in the country’s respective national language and hence frequently disregarded by Western researchers (cf. Funari 2009). Slavic languages are usually not taught in Western European schools making language a fundamental obstacle to the inclusion of Eastern European data in research conducted by Western Europeans. Notably, this problem is largely unidirectional since in Eastern European states, English and German (and Russian) are widely known and taught foreign languages, whilst for example Polish or Czech are of no significance in either Central or Western Europe (European Commision 2005). In addition, Western European researchers remain over-represented in high-profile publication media, as exemplified by, for instance the impactful Journal of Archaeological Science (Butzer 2009). These publications, in turn, are increasingly expensive to access, which creates additional barriers to democratic knowledge exchange across not only extant linguistic but also coincident economic boundaries.

Whilst subtle in isolation, these epistemic and logistic factors together have led to the lamentable status where publications from Western Europe will much more likely find recognition in Eastern European works, but not vice versa. Within the Late Glacial record analysed here, this is evident in the fact that units commonly do not cross the linguistic divide between Germanic and Slavic languages (cf. Figures 2 and 5). Only in rare cases, this problem was deliberately addressed (cf. Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1979: 7), but it is telling that the Tarnowian, which was originally understood to be a high-level taxonomic unit on par with a culture or even a cultural circle also encompassing the Azilian (see Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1977: 177), the Federmessergruppen and the Romanellian (Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1979: 53), has rarely been incorporated into Western research but always been kept separate and described as a subcultural entity (Taute 1963) and variant (Kozłowski et al.1996: 83f). Conversely, the term Lyngby culture remains in common usage in Eastern Europe (e.g. Girininkas et al.2016; Migal 2006; Sinitsyna 2002), despite the fact that it has long been all but abandoned by Scandinavian researchers (Brinch Petersen 1970). The only other units spanning both zones were the ones defined by Taute (1968) owing to the comprehensiveness of his seminal work.

Comparing Extant Taxonomic Units

Besides typological criteria, numerical characteristics in the form of relative tool frequencies are often used to delimit local units. This approach, reminiscent of Bordian-type frequency notions, is especially prevalent in the Eastern European research tradition (Chmielewska 1961; Chmielewski 1961; Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1977, 1979; Kozłowski et al.1996; Krukowski 1939; Schild 1960, 1965, 1975; Vencl 1966, 1970a, b), although by no means exclusively so (Nielsen 2002, 2009; Salomonsson 1964; Wyss 1953, 1968).

Typically, the dominance of a specific tool type, like the burin in the case of the Swiss Fürstein group (Wyss 1953, 1968) or the short end-scraper in the case of the Polish Tarnowian (Schild 1960), is used to circumscribe a regionally distinct unit of the Late Palaeolithic (cf. Figure 6). Tool frequencies are contingent on a variety of past factors as well as post-depositional transformations, including sorting and collecting biases (Ammermann and Feldmann 1974; Baker 1978; Dunnell and Simek 1995; Veil 1987). In well-constrained assemblages, tool frequencies are likely to represent functional aspects of a specific site category (Zimmermann et al.2004), or they may relate to the length and intensity of occupation, especially when coupled with site function, which has been demonstrated for backed bladelets in the Magdalenian (Parkington et al.1980; Richter 1990; Straus 2006: 505f) and has been stated for other tool types such as antler harpoons (Straus 2006: 503). A further major driving force behind tool frequencies may be ecological patterning. For example, regional geomorphology determines characteristics and diversity of economic opportunities in the vicinity of a given site and within a given climatic setting (Burnett et al.1998; Parkington et al.1980; Sauer 2018; Straus 2006: 504; Zimmermann and Thom 1982). This close connection between tool frequencies and specific habitats can be observed in the Fürstein group, for instance (cf. Figure 6). Find spots showing high frequencies of burins are situated in the peat bogs of the Wauwiler Moos (the former Lake Wauwil, drained in the nineteenth century) in Switzerland and around the Federsee in southern Germany (Eberhardt et al.1987; Jochim et al.2015). It is possible that the marshy landscapes surrounding these lakes or the exploitation of aquatic resources demanded the intense use of specific tools or toolsets, although the specific causal pathway remains obscure. In the lowlands of Northern Germany (Trölsch 1976), Poland (Taute 1968) and Denmark (Johansson 2003; Petersen 1994), equally high frequencies of burins can be observed, which further underlines this tool type’s possible association with a wetland-oriented ecological and economic context. Although burins are commonly thought of as tools used on hard materials like antler and bone, their use for working other materials, also relatively soft ones, has been shown as well (Barton et al.1996; Iwase 2014: 366).

Interpolated relative frequencies of backed pieces (orange), burins (red), tanged points (blue) and end-scrapers (green); darker colours indicate higher frequencies of the respective tool type (basis for relative frequencies is the sum of backed pieces, burins, end-scrapers and tanged points; interpolation parameters in SAGA: inverse distance weighting; max search distance 7; number of points: min 1, max 20; weighting: exponential; bandwidth: 0.3; projection: UTM32N; EPSG: 7416; Data: Natural Earth Data); the data used for processing is contained in Electronic Supplementary Table 2

The increasing occurrence of large tanged points in Federmessergruppen assemblages at higher latitudes (cf. Figure 7) may also signal a relative shift in the importance of heavier armatures—delivered by spear-thrower—used against thick-skinned ungulates such as elk and giant deer in more open habitats (Bokelmann 1978; Dev and Riede 2012; Riede 2009, 2017). Importantly, however, the occurrence of such large tanged points is not exclusive to any one cultural unit in the Late Palaeolithic, but a general artefact class occurring in low frequencies within many assemblages. This seriously compromises the culturally diagnostic value of these tools.

Overlay of the interpolated distribution of tanged points (blue) and backed pieces (orange indicates backed bladelets and arch-backed points); it is apparent, that there is no exclusive distribution of both tool types, which also frequently co-occur at sites with arch-backed points and tanged points, respectively (black dots indicate sites with co-occurrence of arch-backed points and tanged points; the basis for relative frequencies is the sum of backed pieces, burins, end-scrapers and tanged points; interpolation parameters in SAGA: inverse distance weighting; max search distance 7; number of points: min 1, max 20; weighting: exponential; bandwidth: 0.3; projection: UTM32N; EPSG: 7416; Data: Natural Earth Data); the data used for processing is contained in Electronic Supplementary Table 2

The occurrence of sites with supposed Tarnowian characteristics is even more widespread and diffuse. Although high frequencies of end-scrapers are supposed to be a feature of Eastern European regional groups such as the Tarnowian, Witowian and the Ostroměr groups, they can be observed throughout most of the study area, without a clear association with specific palaeoecological or geomorphological settings—scrapers of this kind are simply the most common tool in the vast majority of all Late Palaeolithic assemblages. This ubiquity makes the tool class itself patently unsuitable as a regional cultural marker.

In all this, it is critical to recall that the bulk of sites used for the definition of local units is composed of surface collections (Beck et al.2009; Naber 1974; Nielsen 2009; Schönweiß 1967, 1974, 1992; Szymczak 1984, 1987; Taute 1963, 1968; Vencl 1970a, b). This not only makes them hard to date (Crombé et al.2013; Vermeersch 1977), or to unravel whether they reflect single or multiple occupation episodes, it also has implications for the use of tool frequencies derived from such collections. Especially with regard to smaller assemblages, relative tool frequencies have to be considered with utmost caution given that a variety of stochastic and difficult-to-account-for processes come into play (Ammermann and Feldmann 1974; Baker 1978; Dunnell and Simek 1995; Veil 1987): size sorting due to post-depositional processes, collection bias with regard to size and collection bias with regard to recognisability. Whilst challenging to demonstrate at the level of individual sites, this can be observed with regard to the large tanged points in the study area, which are relatively easy to recognise and typically have larger dimensions than arch-backed points. This has led to a likely overemphasis of this tool class when it comes to assigning assemblages to a given taxonomic unit (Riede 2017). In southern Scandinavia, these stochastic biases are further coupled with subtle forms of confirmation bias. Whilst the Bromme culture has the oldest pedigree of all regional Late Palaeolithic taxonomic units, it was only recognised from the 1970s onwards that arch-backed points occurred in the region at all. This has led to a discounting of arch-backed elements in many known assemblages and hence a significant underreporting of these components in reports, publications and the national finds database (Riede 2013, 2017).

A comparable situation holds true with regard to the Bavarian heritage archives, where sites are assigned to the Late Palaeolithic whenever clearly diagnostic types for other Palaeolithic periods are absent or specific raw materials are present. As with the Bromme culture in Denmark, this makes the Late Palaeolithic a form of default taxonomic group with an evident tendency for the registration of Palaeolithic sites to be strongly related to the archaeologist at the responsible heritage administration (Sauer 2018). In southern Scandinavia, avocational collectors—often motivated by a keen interest in ‘Heimatkunde’ or local history—have also fondly focussed on the Bromme culture in favour of other Late Palaeolithic entities, not least because the eponymous site itself was discovered by an avocational archaeologist (Fischer 2002). Recent discussion of these issues has opened the debate on whether the Bromme culture (Buck Pedersen 2014; Buck Pedersen 2015; Kobusiewicz 2009b; Riede 2013, 2014, 2017) and along with it similar phenomena in Eastern Europe that have been defined with reference to it (Sulgostowska 1989; Kobusiewicz 2009a) can at all be maintained as valid taxonomic units or whether they should be sunk into the wider arch-backed point complex as functional variants or facies.

The application of raw material as a taxonomic criterion is reflected most acutely in the definition of the Bavarian subset of the Atzenhof group. This unit was first described by the avocational archaeologist Werner Schönweiß (Kaulich 2003) in 1974, based on the surface collections from Fürth-Atzenhof and Fürth-Flexdorf. Schönweiß (1967, 1968) began to use this taxonomic term already in the 1960s, albeit without offering a clear classificatory definition. Alongside the unspecified presence of backed tools and burins (and the issues associated with tool frequencies in surface assemblages), the most important characteristic is supposed to be the use of a specific set of raw materials (Schönweiß 1974, 1992; Werner and Schönweiß 1974). Whilst local materials such as Jurassic chert, Tabular chert, Chalcedony, Upper Triassic chert and lydite make up the bulk of the tool stone, it is supplemented by products made from erratic flint transported over at least a distance of 180 km from the moraines in Thuringia and Saxony (Sauer 2018).

This raw material-based definition is problematic in a variety of ways, however. First and foremost, raw material use is most strongly influenced by the availability and accessibility of suitable tool stone in a given area, i.e. it is strongly spatially autocorrelated. It is unlikely that raw materials were used by Late Glacial foragers to signal group identity (Clark 1988: 4). At any rate, it has to be noted in this context that similar raw material usage can also be observed in sites of the north-western Czech Republic (Sauer 2017; Vencl 1970a, b), although these regions are not thought to be part of the Atzenhof group. Instead of signalling group identity, raw material compositions essentially indicate the supraregional connection of the sites in northern Bavaria to the Danube region to the south and to the moraines along the margins of the lowlands to the north (Sauer 2017). Assuming embedded procurement as the dominant mode of lithic resource acquisition, this would add up to an annual round of at least 400 km in distance. This then reflects the general connectedness of Late Palaeolithic people to distant regions, rather than the autonomy of regional entities (Baales 2002, 2003, 2004). Such transport of lithic raw materials over long distances is a characteristic of the Late Palaeolithic (Baales 2003; Floss 1994).

Based on these raw material distribution patterns, past mobility can be reconstructed particularly well in the geologically heterogeneous landscapes of the Central European low mountain ranges, which provide numerous easy-to-distinguish tool stone variants (Binsteiner 2005; Floss 1994; Löhr and Schönweiß 1987; Malkovský and Vencl 1995; Sauer 2017; Weißmüller 1995). In the Northern European Lowlands, this situation is much harder to decode, due to the almost exclusive availability and use of erratic flint (Madsen 1993). In contrast, the large size and generally high quality of northern erratic flint released knapping from volumetric constraints, mimicking cultural specificity. Yet, large nodule size is merely a necessary yet not a sufficient argument driving large tool sizes. Changes in the bulk of knapping debris hence make it exceedingly difficult to differentiate Federmessergruppen from Bromme culture assemblages in the absence of (supposedly) diagnostic tools (Eriksen 2000). The recent critiques of the use of large tanged points as a culturally diagnostic artefact class, coupled with the evident difficulty of distinguishing knapping products together stress the weak basis on which taxonomic units such as the Bromme culture or the Perstunian—a purported eastern European culture similar to the Bromme culture (Szymczak 1987, 1999)—are founded (Table 1).

Finally, the areal extent of most local Late Palaeolithic taxonomic units, such as the Atzenhof or the Fürstein group, falls short of comparable territory sizes (Table 3) known from ecologically comparable ethnographic foragers (Binford 2001; Kelly 1995; Newell and Constandse-Westermann 1996: 384). Whilst prehistoric reality may differ substantially from that of the ethnographic present (Wobst 1978), the marked divergence of many of the most locally defined units especially but also the substantive variation in territory sizes for these Late Palaeolithic entities speaks against them reflecting meaningful analytical units in the sense of identity-conscious ethnic or linguistic communities. Note also again that the rather large areas not inhabited by any kind of Late Palaeolithic subculture, group or industry still harbour Late Palaeolithic sites (Heinen 2005; Taute 1972)—current taxonomic schemes account poorly if at all for these unassigned sites.

Discussion

The practice of classifying and subdividing archaeological cultures is closely related to the culture-historical research paradigm which focusses on the description of the “what, where and when” (Binford 1964: 425) of archaeological remains. In this way, archaeologists sought to describe the makeup and succession of social units which were believed to be detectable in the artefacts and sites that were left behind by prehistoric people (Clark 1994: 329; Clark and Lindly 1991; Kozłowski and Kozłowski 1979: 16; Vasil’ev 2001: 4). Either typological, functional or economic criteria were used as proxies representing social units. With the advent of New Archaeology—most prominently promoted by Lewis Binford in a number of seminal articles (e.g. Binford 1962, 1964)—the research questions changed towards the analysis of processes of change and the ‘how and why’ (Binford 1964: 425) of prehistoric development. In this context, the mere classification of archaeological remains did not help to answer the research questions of the day.

In the context of the Central European Late Palaeolithic, this paradigm change is reflected in the almost complete cessation of definitions of new regional units—cultures—after 1974. The Perstunian culture, first described in 1987 as an eastern European parallel to the southern Scandinavian Bromme culture, is the only exception to this pattern (Szymczak 1987), although it was heavily criticised for its typological inconsistency and the reliance on poorly constrained assemblages already shortly after being proposed (Sulgostowska 1989, and see Szymczak 1991 for a response)—a particular debate that to all intents and purposes mirrors our comparative and more general discussion of the Atzenhof and Fürstein groups and the Bromme culture presented here. With notable exceptions (Newell and Constandse-Westermann 1996), the methodological re-orientation of the New Archaeology did not, however, lead to a critical reassessment of Late Palaeolithic taxonomies. In fact, collectors in Franconia still attribute assemblages to the Late Palaeolithic and even the Atzenhof group despite the absence of diagnostic tool types (Sauer 2018); workers in Eastern Europe still attribute local assemblages to the Perstunian culture or related large tanged point groups of Eastern Europe despite their problematic classificatory foundation (Siemaszko 1999; Sinitsyna 2002); and in southern Scandinavia, the Bromme culture remains enshrined as the first regional culture (Price 2015). Yet, in line with Clark’s (2009: 19) discussion of cultural taxonomic issues in the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, we have shown that the current Late Palaeolithic taxonomies in Europe are largely “accidents of history” and that many of the traditional archaeological taxonomic for this period may be “phantom cultures” (Barton and Neeley 1996: 146).

More recently and as part of a broad development within evolutionary archaeology, attention has turned to demography and cultural transmission as important factors generating spatio-temporal variability in the archaeological record, effectively bringing the traditional culture-historical research questions of ‘what, when, and where’ to the fore once more (Roberts and Vander Linden 2011; Shennan 1989, 1995, 2006). With this contemporary re-orientation towards culture history has also come a renewed focus on the construction of the necessary taxonomic units and how to analyse them (Lipo et al.2006; O'Brien et al. 2008; Riede 2011b). In this view, cultures or any other formally named taxonomic unit is understood as a materialist, population-level phenomenon that is generated through the actions of individuals and that assumes archaeological shape through the consistent socially learned repetition of such actions across generations. These can be read as more or less stable bundles of material culture characters and as representing communities of practice over time, but they are not claimed to in any straightforward way correspond to cultures as defined by anthropologists (O'Brien et al.2008).

There has been significant debate about whether and to what degree lithic typology in particular reflects identity-conscious communities similar to those identifiable in the ethnographic present, and also whether we would be able to recognise them: “Information about group membership must be encoded in lithics in such a way that it can be decoded by prehistoric recipients and by archaeologists” (Barton 1997: 144). Our critical and comparative investigation of Central European Late Palaeolithic taxonomies has raised the question of whether Barton’s basic requirement is met by the key classificatory characteristics used (index fossil types, tool frequencies, raw material selection) and whether we may be dealing with active or passive identity carriers (Barton 1997: 143). We conclude that tool frequency is unlikely to be a passive carrier of group identity (Barton 1997: 142) since it is related to functional characteristics of a given site as well as stochastic post-depositional factors. If understood as an active identifier, frequency characteristics could hardly be monitored by any prehistoric individual, since any given assemblage’s specific characteristics are only visible if perceived in their entirety. In addition, sites can be used consecutively by different groups employing the same general tool spectrum, and group size and composition may change in the course of the annual round, which may strongly impact any artefact frequencies (Barton 1997: 148).

Turning to the artefacts themselves, Barton argues that lithic tool types and variants are poor active transmitters of social information owing to their typically small size (Sackett 1985; Wiessner 1985). It is worth remembering, too, that lithics almost certainly only played a very minor role in the overall toolkit given the inverse relationship between the importance of organic tool components in traditional societies and their likelihood of preservation (Stodiek and Paulsen 1996). Visibility is a fundamental characteristic of sociocultural identifiers (Carr 1995; Tostevin 2013) making it unlikely that Late Pleistocene group identities were connected specifically to some of the smallest and most mundane items in their material culture repertoire. Instead, individual group membership should be evident from great distances. In the arrows in the Great Basin, NV, USA, for instance, these identifying characteristics are attached to the shaft, and not the lithic point (Sinopoli 1991). Nonetheless, different manufacturing techniques and tool variants may represent the best opportunities for identifying Late Palaeolithic social units (Collard and Shennan 2008). In doing so, a multitude of other influences such as weapon delivery systems used, the prey hunted and tool stone size must be taken into consideration as they have the potential to eliminate or distort any archaeologically discernable social markers (Barton 1997; Myers 1989; Shott 1996). However, many tool types used for such exercises have been defined a long time ago and have rarely been subjected to rigorous re-analysis. Whenever such analyses have been conducted, however, few if any traditional typological divisions stand up to statistical and especially morphometric scrutiny (e.g. Bisson 2000; Ikinger 1998; O'Brien et al.2014; Serwatka and Riede 2016).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have subjected the current patchwork of Central European Late Palaeolithic taxonomic groups to a critical and rigorous comparative analysis. This taxonomic health check has revealed a great deal of heterogeneity in how these units are constructed. As a consequence, different taxonomic systems are not mutually comparable. Many units are—despite vernacular labels (culture, group) that imply taxonomic interoperability—not readily compatible. We argue that the use of tool frequencies as a defining characteristic for some of these taxonomic units does not account sufficiently for stochastic and taphonomic factors as confounders of any observed patterns. We further argue that the use of index-type artefacts likewise does not work sufficiently well for clearly demarcating Late Palaeolithic taxonomic units and their spatial extent. Type definitions are often imprecise, and research conducted after the initial definition of a given taxonomic group based on one or several specific index types (e.g. large tanged points) has repeatedly shown their diffuse presence in many Late Palaeolithic assemblages. Such occurrences may be more parsimoniously explained against a background of ecological and economic differences and using behavioural ecological approaches.

In many if not all cases, the suggested cultures and groups of the Late Palaeolithic reflect a patterning unlikely, in our view, to represent the actual prehistoric ethnolinguistic makeup. We are painfully aware of the potential implications of our negative results, but underline that our paper should not be read as a critique of any specific attempt at classifying Late Palaeolithic assemblages (cf. Clark 2009). We share most archaeologists’ interest in writing and understanding culture histories, for which the construction of adequate and operational taxonomies is essential. We do not offer an alternative taxonomy for the Central European Palaeolithic here, but stress that the classificatory system or rather the classificatory systems in place at present are research historically, methodologically and empirically flawed. Falling short of offering a workable alternative, we note that palaeobiologists regularly struggle with similarly thorny taxonomic issues. In palaeobiology, traditional quasi-typological approaches (cf. Mayr 1976) were, however, quickly replaced by taxonomic definitions that were operationalised through population thinking, statistical reasoning and computer applications (Hagen 2001). Especially tree-thinking and phylogenetic approaches now dominate as they, once operational units are defined, order these hierarchically in explicitly nested sets (e.g. O'Brien et al. 2002; Riede 2011a). In their brief but lucid discussion of archaeological taxonomic units for the Late Palaeolithic, Gamble et al. (2005) have gone some way towards constructing an operational taxonomy based on a hierarchy of attributes and clusters thereof. In parallel, approaches employing geometric morphometric analyses of key Late Pleistocene artefact classes and linking observed changes in shape and technology explicitly to models of cultural transmission have also been gaining traction in North America (e.g. O'Brien and Buchanan 2017; Sholts et al.2017). Together, these may serve as inspiration for researchers working in the European Late Palaeolithic. Building on these efforts, we suggest that future attempts at systematically ordering Late Palaeolithic material culture should draw on explicit attribute-based and geometric morphometric principles with the aim of statistically comparing the resulting units. The units and the hierarchies in which they are nested can then be used for further analyses that investigate material culture variation in relation to chronology, ecology, economy and geomorphology.

References

Ammermann, A., & Feldmann, M. (1974). On the “making” of an assemblage of stone tools. American Antiquity, 39(4), 610–616.

Baales, M. (2002). Der Spätpaläolithische Fundplatz Kettig. Untersuchungen zur Siedlungsarchäologie der Federmesser-Gruppen am Mittelrhein. Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

Baales, M. (2003). Umwelt und Archäologie der spätpaläolithischen Federmesser-Gruppen am Mittelrhein (Rheinland-Pfalz). Praehistorica Thuringica, 9, 35–50.

Baales, M. (2004). Local and regional economic systems of the Central Rhineland Final Paleolithic. In L. S. d. Congrès (Ed.), Le Mésolithique/The Mesolithic (Vol. 1302, pp. 3–9). Oxford: BAR International Series.

Bailey, G. N., & Spikins, P. (Eds.). (2008). Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, C. M. (1978). The size effect: an explanation of variability in surface artifact assemblage content. American Antiquity, 43(2), 288–293.

Barton, M. (1997). Stone tools, style, and social identity: an evolutionary perspective on the archaeological record. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, 7(1), 141–156.

Barton, C. M., & Neeley, M. P. (1996). Phantom cultures of the Levantine Epipaleolithic. Antiquity, 70(267), 139–147.

Barton, M., Olzewski, D., & Coinman, N. (1996). Beyond the graver: reconsidering burin function. Journal of Field Archaeology, 23(1), 111–125.

Beck, M., Beckert, S., Feldmann, S., Kaulich, B., & Pasda, C. (2009). Das Spätpaläolithikum und Mesolithikum in Franken und der Oberpfalz. Bericht der Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege, 50, 269–291.

Bergsvik, K. A. (2003). Mesolithic ethnicity—too hard to handle. In L. Larsson, H. Kindgren, K. Knutsson, D. Loeffler, & A. Åkerlund (Eds.), Mesolithic on the move: papers presented at the sixth international conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Stockholm 2000 (pp. 290–302). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Binford, L. R. (1962). Archaeology as anthropology. American Antiquity, 28(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/278380.

Binford, L. R. (1964). A consideration of archaeological research design. American Antiquity, 29(4), 425–441.

Binford, L. R. (2001). Constructing frames of reference: an analytical method for archaeological theory building using hunter-gatherer and environmental data sets. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Binsteiner, A. (2005). Die Lagerstätten und der Abbau bayerischer Jurahornsteine sowie deren Distribution im Neolithikum Mittel- und Osteuropas. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 52, 43–155.

Bisson, M. S. (2000). Nineteenth century tools for twenty-first century archaeology? Why the Middle Paleolithic typology of François Bordes must be replaced. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 7(1), 1–48.

Bokelmann, K. (1978). Ein Federmesserfundplatz bei Schalkholz, Kreis Dithmarschen. Offa, 35, 36–54.

Breest, K., & Gerken, K. (2008). Kulturelle Einflüsse und Beziehungen im Spätpaläolithikum Niedersachsens – Ein Diskussionsbeitrag Sassenholz 78 und 82, Ldkr. Rotenburg (Wümme). Die Kunde N.F, 59, 1–38.

Brinch Petersen, E. (1970). Le Brommeen et le cycle de Lyngby. Quartär, 21, 93–95.

Brinch Petersen, E. (2009). The human settlement of southern Scandinavia 12500–8700 cal BC. In M. Street, R. N. E. Barton, & T. Terberger (Eds.), Humans, environment and chronology of the late glacial of the North European Plain (pp. 89–129, RGZM – Tagungen, Band 6)). Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums.

Buck Pedersen, K. (2014). Brommeproblemet 2.0 - kommentarer til Riedes artikel ‘Brommeproblemet’. Arkæologisk Forum, 30, 7–11.

Buck Pedersen, K. (2015). Brommekulturen lever! Arkæologisk Forum, 32, 37–41.

Burdukiewicz, J. (1999). Z problematyki paleolitu Sudetów. In P. Valde-Nowak (Ed.), Początki osadnictwa w Sudetach (pp. 35–52). Krakau: Instytut Archeologii i Etnologii.

Burnett, M. R., August, P. V., Brown, J. H., & Killingbeck, K. T. (1998). The influence of geomorphological heterogeneity on biodiversity I. A patch-scale perspective. Conservation Biology, 12(2), 363–370.

Butzer, K. W. (2009). Evolution of an interdisciplinary enterprise: the Journal of Archaeological Science at 35 years. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(9), 1842–1846.

Carr, C. (1995). A unified middle-range theory of artifact design. In C. Carr & J. Neitzel (Eds.), Style, society, and person: archaeological and ethnological perspectives (pp. 171–258). New York: Plenum.

Chmielewska, M. (1961). Huttes d’habitation épipaléolithiques de Witów, district de Leczyca. Acta Archaeologica Universitatis Lodziensis, 10, 1–137.

Chmielewski, W. (1961). Civilisations épipaléolithiques en Pologne centrale. Bulletin de la Société des Sciences et des Lettres de Lódz, 12, 1-passim.

Clark, G. A. (1988). The Upper Paleolithic of northeast Asia and its relevance to the first Americans: a personal view. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 5, 3–6.

Clark, G. A. (1994). Migration as an explanatory concept in Palaeolithic archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1(4), 305–343.

Clark, G. A. (1996). Plus français que les Français. Antiquity, 70(267), 138–139.

Clark, G. A. (1999). Highly visible, curiously intangible. Science, 283(5410), 2029–2032.

Clark, G. A. (2009). Accidents of history: conceptual frameworks in paleoarchaeology. In M. Camps & P. Chauhan (Eds.), Sourcebook of Paleolithic transitions: methods, theories, and interpretations (pp. 19–41). New York: Springer.

Clark, G. A., & Lindly, J. (1991). On paradigmatic biases and Paleolithic research traditions. Current Anthropology, 32(5), 577–587.

Clark, G. A., & Riel-Salvatore, J. (2006). Observations on systematics in Paleolithic archaeology. In E. Hovers & S. L. Kuhn (Eds.), Transitions before the transition: evolution and stability in the middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age (pp. 29–56). Boston: Springer US.

Clarke, D. (1968). Analytical archaeology. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd..

Collard, M., & Shennan, S. J. (2008). Patterns, process, and parsimony: studying cultural evolution with analytical techniques from evolutionary biology. In M. T. Stark, B. J. Bowser, & L. Horne (Eds.), Cultural transmission and material culture (pp. 17–33). Tucson: The University of Tucson Press.

Crombé, P. H., Robinson, E., Van Strydonck, M., & Boudin, M. (2013). Radiocarbon dating of Mesolithic open-air sites in the coversand area of the north-west European Plain: problems and prospects. Archaeometry, 55(3), 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2012.00693.x.

De Bie, M., & Vermeersch, P. M. (1998). Pleistocene-Holocene transition in the Benelux. Quaternary International, 49/50, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1040-6182(97)00052-9.

Dev, S., & Riede, F. (2012). Quantitative functional analysis of Late Glacial projectile points from northern Europe. Lithics, 33, 40–55.

Dobat, A. S. (2013). Var der nogensinde en ‘vikingetid’? In H. Lyngström & L. G. Thomson (Eds.), Vikingetid i Danmark (pp. 25–28). Copenhagen: Københavns Universitet, Det Humanistiske Fakultet.

Dunnell, R. C., & Simek, J. F. (1995). Artifact size and plowzone processes. Journal of Field Archaeology, 22(3), 305–319.

Eberhardt, H., Keefer, E., Kind, C.-J., Rensch, H., & Ziegler, H. (1987). Jungpaläolithische und mesolithische Fundstellen aus der Aichbühler Bucht. Auswertung von Oberflächenfunden aus dem südlichen Federseegebiet. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg, 12, 1–51.

Ekholm, G. (1925). Die erste Besiedlung des Ostseegebietes. Wiener Prähistorische Zeitschrift, XII, 1–16.

Eriksen, B. V. (1999). Late Palaeolithic settlement in Denmark—how do we read the record? In M. Kobusiewicz, & J. K. Kozlowski (Eds.), Post-Pleniglacial re-colonisation of the Great European Lowland (Vol. Folia Quaternaria 70, pp. 157–174). Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejetnosci.

Eriksen, B. V. (2000). Patterns of ethnogeographic variability in Late Pleistocene Western Europe. In G. L. Peterkin, & H. A. Price (Eds.), Regional approaches to adaptation in Late Pleistocene Western Europe (pp. 147–168, BAR (IS) 896). Oxford: Oxbow.

European Commision. (2005). Europeans and languages. Eurobarometer, 63(4).

Felgenhauer, F. (1996). Aggsbachien - Gravettien - Pavlovien Zur Frage nomenklatorischer Prioritäten in der Urgeschichtsforschung. Mitteilungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, CXXV/CXXVI, 249–257.

Fellner, R. (1995). Technology or typology?: a response to Neeley & Barton. Antiquity, 69(263), 381–383.

Fischer, A. (1985). Late Paleolithic finds. In K. Kristiansen (Ed.), Archaeological formation processes. The representativity of archaeological remains from Danish Prehistory (pp. 81–88). Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet.

Fischer, A. (2002). Arkæologen Erik Westerby: frontforsker på fritidsbasis. Kuml, 2002, 35–64.

Floss, H. (1994). Rohmaterialversorgung im Paläolithikum des Mittelrheingebietes (Monographien) (Vol. 21). Bonn: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

Funari, P. P. (2009). Historical archaeology and global justice. Historical Archaeology, 43(4), 120–121.

Gamble, C., William, D., Pettitt, P., Hazelwood, L., Richards, M. (2005). The Archaeological and Genetic Foundations of the European Population during the Late Glacial: Implications for 'Agricultural Thinking'. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 15 (2), 193-223.

Girininkas, A., Ruimkus, T., Slah, G., Daugnora, L., Stančikaitė, M., & Zabiela, G. (2016). Lyngby type artefacts of Lithuania in the context of the Stone Age in Europe: multidisciplinary study. Arheologija un etnografija, 29, 13–30.

Goring-Morris, A. N. (1996). Square pegs into round holes: a critique of Neeley & Barton. Antiquity, 70(267), 130–135.

Hagen, J. (2001). The introduction of computers into systematic research in the United States during the 1960s. Studies in the History and Philosophy of the Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 32, 291–314.

Heffley, S. (1981). The relationship between northern Athapaskan settlement patterns and resource distribution: an application of Horn’s model. In B. Winterhalder & E. A. Smith (Eds.), Hunter gatherer foraging strategies: ethnographic an archaeological analyses. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

Heinen, M. (2005). Sarching '83 und '89/90. Untersuchungen zum Spätpaläolithikum und Frühmesolithikum in Südost-Deutschland (Vol. 1, Edition Mesolithikum ed.). Loogh: Welt und Erde.

Hobsbawn, E. (1983). Introduction: inventing traditions. In E. Hobsbawn & T. Ranger (Eds.), The invention of tradition (pp. 1–14). Cambridge.

Høgh, L. (2008). Kulturheltens arv – Arkæologiens nationalvidenskabelige forpligtelse. Arkæologisk Forum, 18, 2–7.

Horn, H. S. (1968). The adaptive significance of colonial nesting in the Brewers blackbird (Euphagus cyanocephalus). Ecology, 49(4), 682–694.

Houtsma, P., Kramer, E., Newell, R., & Smit, J. L. (1996). The Late Palaeolithic habitation of Haule V: from excavation report to the reconstruction of Federmesser settlement patterns and land-use. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Ikinger, E.-M. (1998). Der endeiszeitliche Rückenspitzen-Kreis Mitteleuropas (GeoArchaeoRhein, Nr.1). Münster: LIT.

Iwase, A. (2014). Consideration of burin-blow function: use wear analysis on Kamiyama-type burin of Sugikubo blade industry in central Japan. In J. Marreiros, J. Frerreira Bicho, & J. Gibaja Bao (Eds.), International conference on use-wear analysis: use-wear 2012 (pp. 362–374). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Jessen, A. H., & Nordmann, V. J. H. (1915). Ferskvandslagene ved Nørre Lyngby (Vol. 29, Dansk Geologiske Undersøgelse, II. Række, No.29)). Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzel.

Jochim, M., Kind, C.-J., Kleinmann, A., Merkt, J., & Stephan, E. (2015). Eine spätpaläolithische Fundstelle am Ufer des Federsees: Bad Buchau-Kappel, Flurstück Gemeindebeunden. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg, 35, 37–134.

Johansson, A. D. (2003). Stoksbjerg Vest. Et Senpalæolitisk Fundkompleks Ved Porsmose, Sydsjælland. Fra Bromme- Til Ahrensburgkultur I Norden. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

Kane, S. (2003). Introduction. In S. Kane (Ed.), The politics of archaeology and identity in a global context (pp. 1–9). Boston: Archaeological Institute of America.

Kaufman, D. (1995). Microburins and microliths of the Levantine Epipalaeolithic: a comment on the paper by Neely & Barton. Antiquity, 69(263), 375–381.

Kaulich, B. (2003). Schriftenverzeichnis von Werner Schönweiß. Natur und Mensch, 13–18.

Kelly, R. L. (1995). The foraging spectrum: diversity in hunter-gatherer lifeways. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Kluxen, A., & Hecht, J. (2010). Der Tag der Franken. Geschichte - Anspruch - Wirklichkeit. Würzburg: Ergon Verlag.

Kobusiewicz, M. (1999). Ahrensburgian and Swiderian: two different modes of adaptation. In Recent Studies in the Final Palaeolithic of the European Plain (Vol. 14, pp. 117-122). Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Kobusiewicz, M. (2009a). The Lyngby point as a cultural marker. In M. Street, R. N. E. Barton, & T. Terberger (Eds.), Humans, environment and chronology of the late glacial of the North European Plain (pp. 169–178, RGZM – Tagungen, Band 6). Mainz: Verlag des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums.

Kobusiewicz, M. (2009b). Whether the Bromme culture existed? Folia Praehistorica Posnaniensia, XV, 75–91.

Kohl, P. L. (2012). Ethnic identity and the anthropological relevance of archaeology. In M. Rockman & J. Flatman (Eds.), Archaeology in society (pp. 229–236). New York: Springer.

Koop, V. (2012). Himmlers Germanenwahn. Berlin: be.bra Verlag.

Kozłowski, J. K., & Kozłowski, S. K. (1977). Epoka kamiena na ziemiach polskich. Warschau.

Kozlowski, J. K., & Kozlowski, S. K. (1979). Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Europe. Taxonomy and palaeohistory (Vol. 18). Wrocław: Prace Komisji Archeologicznej.

Kozłowski, J. K., & Kozłowski, S. K. (1979). Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic in Europe: taxonomy and palaeohistory (Vol. 18). Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich.

Kozłowski, J. K., Kozłowski, S. K., & Kamińska, J. (1996). Le paléolithique en Pologne (Vol. 2). Grenoble: Editions Jérôme Millon.

Kristiansen, K. (1993). The strength of the past and its great might: an essay on the use of the past. Journal of European Archaeology, 1(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1179/096576693800731172.

Krukowski, S. (1939). Prehistoria ziem polskich 1. Krakau: Paleolit.

Lipo, C. P., O’Brien, M. J., Collard, M., & Shennan, S. J. (Eds.). (2006). Mapping our ancestors. Phylogenetic approaches in anthropology and prehistory. New Brunswick, NJ: AldineTransaction.

Löhr, H., & Schönweiß, W. (1987). Keuperhornstein und seine natürlichen Vorkommen. Archäologische Informationen, 10(2), 126–137.

Madsen, B. (1993). Flint—extraction, manufacture and distribution. In S. Hvaas & B. Storgaard (Eds.), Digging into the past. 25 years of archaeology in Denmark (pp. 126–129). Jutland Archaeological Society: Højbjerg.

Malkovský, M., & Vencl, S. (1995). Quartzites of north-west Bohemia as stone age raw materials: environs of the towns of Most and Kadaň. Czech Republic. Památky archeologické, 86, 5–37.

Mathiassen, T. (1946). En senglacial boplads ved Bromme. Aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, 1946, 121–197.

Mayr, E. (1976). Typological versus population thinking. In E. Mayr (Ed.), Evolution and the diversity of life: selected essays (pp. 26–29). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Migal, W. (2006). On various methods of Lyngby point production. In A. Wiśniewski, T. Płonka, & J. M. Burdukiewicz (Eds.), The stone: technique and technology (pp. 137–148). Wrocław: Institute of Archaeology Wrocław.

Montelius, G. O. A. (1903). Die Typologische Methode. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wicksell.

Myers, A. (1989). Reliable and maintainable technological strategies in the Mesolithic of mainland Britain. In R. Torrence (Ed.), Time, energy and stone tools (pp. 78–91). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Naber, F. (1974). Fränkisches Epipaläolithikum. Gliederung und Chronologie. Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, 8, 227–233.

Neeley, M. P., & Barton, M. P. (1994). A new approach to interpreting late Pleistocene microlithic industries in southwest Asia. Antiquity, 68(259), 275–288.

Newell, R. R., & Constandse-Westermann, T. S. (1996). The use of ethnographic analyses for researching Late Palaeolithic settlement systems, settlement patterns and land use in the Northwest European Plain. World Archaeology, 27(3), 372–388.

Nielsen, E. (2002). The Lateglacial settlement of the Central Swiss Plateau. In B. V. Eriksen & B. Bratlund (Eds.), Recent studies in the Final Palaeolithic of the European Plain (pp. 189–201). Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Nielsen, E. (2009). Paläolithikum und Mesolithikum in der Zentralschweiz. Luzern: Kantonsarchäologie Luzern.

O'Brien, M. J., & Buchanan, B. (2017). Cultural learning and the Clovis colonization of North America. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 26(6), 270–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21550.

O'Brien, M. J., Lyman, R. L., Saab, Y., Saab, E., Darwent, J., & Glover, D. S. (2002). Two issues in archaeological phylogenetics: taxon construction and outgroup selection. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 215(2), 133–150.

O'Brien, M. J., Lyman, R. L., Collard, M., Holden, C. J., Gray, R. D., & Shennan, S. J. (2008). Transmission, phylogenetics, and the evolution of cultural diversity. In M. J. O’Brien (Ed.), Cultural transmission and archaeology: issues and case studies (pp. 39–58). Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology Press.

O'Brien, M. J., Buchanan, B., & Collard, M. (2014). On the cutting edge: new methods and theory for analyzing stone tools. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 23(4), 128–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21383.

Otte, M., & Keeley, L. H. (1990). The impact of regionalism on Palaeolithic studies. Current Anthropology, 31(5), 577–582.

Parkington, J., Cable, C., Carter, P., Deacon, H., Deacon, J., Humphreys, A., et al. (1980). Time and place: some observations on spatial and temporal patterning in the later stone age sequence in southern Africa[with comments and reply]. The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 35(132), 73–112.

Petersen, F. (1994). Rundebakke. En senpalæolitisk boplads på Knudshoved Odde, Sydsjælland. Aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, 7–40.

Phillips, J. I. (1996). The real nature of variability of Levantine Epipalaeolithic assemblages. Antiquity, 70(267), 137–138.

Piette, E. (1895). Études d'ethnographie Préhistorique I. - Réparation stratigraphique. L'Anthropologie, 6, 276–292.

Price, T. D. (2015). Ancient Scandinavia: an archaeological history from the first humans to the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richter, J. (1990). Diversität als Zeitmaß im Spätmagdalénien. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 20(1990), 249–257.

Riede, F. (2006). The Scandinavian connection. The roots of Darwinian thinking in 19th century Scandinavian archaeology. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 16(1), 4–19.

Riede, F. (2009). The loss and re-introduction of bow-and-arrow technology: a case study from the southern Scandinavian Late Palaeolithic. Lithic Technology, 34(1), 27–45.

Riede, F. (2011a). Adaptation and niche construction in human prehistory: a case study from the southern Scandinavian Late Glacial. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1566), 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0266.

Riede, F. (2011b). Steps towards operationalising an evolutionary archaeological definition of culture. In B. W. Roberts & M. Vander Linden (Eds.), Investigating archaeological cultures. Material culture, variability, and transmission (pp. 245–270). New York, NY: Springer.

Riede, F. (2013). ‘Brommeproblemet’ – senglacial kulturtaksonomi og dens forståelses- og forvaltningsmæssige implikationer. Arkæologisk Forum, 29, 8–14.

Riede, F. (2014). Brommeproblemet 2.1 – et gensvar til Kristoffer Buck Pedersens kommentar. Arkæologisk Forum, 31, 39–45.

Riede, F. (2017). The ‘Bromme problem’—notes on understanding the Federmessergruppen and Bromme culture occupation in southern Scandinavia during the Allerød and early Younger Dryas chronozones. In M. Sørensen & K. Buck Pedersen (Eds.), Problems in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research (Vol. 12, pp. 61–85, Arkæologiske Studier). Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen & Museum of Southeast Denmark.

Riede, F., Laursen, S. T., & Hertz, E. (2011). Federmesser-Gruppen i Danmark. Belyst med udgangspunkt i en amatørarkæologs flintsamling. Kuml, 2011, 9–38.

Rimantiène, R. K. (1971). Paleolit i mezolit Litvy. Vilnius: Mintis.

Roberts, B. W., & Vander Linden, M. (Eds.). (2011). Investigating archaeological cultures. Material culture, variability, and transmission. New York: Springer.

Rust, A. (1937). Das altsteinzeitliche Rentierjägerlager Meiendorf. Neumünster: Wachholtz.

Sackett, J. R. (1985). Style and ethnicity in the Kalahari: a reply to Wiessner. American Antiquity, 50(1), 154–159.

Sackett, J. R. (1991). Straight archaeology French style: the phylogenetic paradigm in historic perspective. In G. A. Clark (Ed.), Perspectives on the past. Theoretical biases in Mediterranean hunter-gatherer research (pp. 109–139). Philadelphia, PE: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Salomonsson, B. (1964). Decouverte d’un habilitation du Tardi-Glaciere a Segebro, Scanie, Suede. Acta Archaeologica, 35(1), 1–28.

Samida, S. (2013). Archäologie und Öffentlichkeit: Zum Stand der Reflexion. In M. K. H. Eggert & U. Veit (Eds.), Theorie in der Archäologie: Zur deutschsprachigen Diskussion (pp. 337–374). Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

Sauer, F. (2017). Raw material procurement economy and mobility in Late Palaeolithic northern Bavaria. Quartär, 63, 125–135.

Sauer, F. (2018). Spätpaläolithische Landnutzungsmuster in Nordbayern. OPUS FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg. URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:29-opus4-92875.

Sawicki, L. (1933). Przemysł świderski I stanowiska wydmowego Świdry Wielkie I. Przegląd Archeologiczny, 5(1), 1–23.

Schild, R. (1960). Extension des éléments de type tarnovien dans les industries de l'extrême fin du pleistocène. Archaeologia Polona, 3, 7–64.

Schild, R. (1965). Remarques sur les Principes de la Systématique Culturelle du Paléolithique (Surtout du Paléolithique Final). Archaeologia Polona, 8, 67–81.

Schild, R. (1975). Prahistoria ziem polskich. Późny paleolit (Vol. 1). Wrocław: Ossolineum.

Schönweiß, W. (1967). Mittelsteinzeit in Franken. Bad Windsheim: Naturhistorische Gesellschaft Nürnberg.

Schönweiß, W. (1968). Eine frühmesolithische Silexgesellschaft von Hochstadt-Gruben, Landkreis Lichtenfels. Quartär, 19, 373–380.

Schönweiß, W. (1974). Fränkisches Epipaläolithikum - Die Atzenhofener Gruppe. Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, 8, 17–108.

Schönweiß, W. (1992). Letzte Eiszeitjäger in der Oberpfalz. Grafenwöhr: Druckerei Hutzler.

Schönweiß, W. (1993). Leupoldsdorf 2 – Das Frühmesolithikum Nordbayerns – Bergbau und Rohstoffgewinnung am Feuerberg bei Wunsiedel. Archiv für Geschichte von Oberfranken, 73, 11–54.

Schönweiß, W. (1997). Neufunde der Endeiszeit aus der nördlichen Oberpfalz. Oberpfälzer Heimat, 41, 7–23.

Schönweiß, W., & Sticht, E. (1968). Das Endpaläolithikum von Plankenfels/Ofr. Archiv für Geschichte von Oberfranken, 48, 71–86.

Schwabedissen, H. (1954). Die Federmesser-Gruppen des nordwesteuropäischen Flachlandes: zur Ausbreitung des Spät-Magdalénien (Vol. 9). Neumünster: K. Wachholtz.

Schwabedissen, H. (1955). Zur Auswertung steinzeitlicher Oberflächenfundplätze. Eiszeitalter & Gegenwart, 6, 159–169.

Schwantes, G. (1939). Die Vorgeschichte Schleswig-Holsteins (Stein und Bronzezeit). Neumünster: Karl Wachholz Verlag.

Serwatka, K., & Riede, F. (2016). 2D geometric morphometric analysis casts doubt on the validity of large tanged points as cultural markers in the European Final Palaeolithic. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 9, 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2016.07.018.

Shea, J. J. (2014). Sink the Mousterian? Named stone tool industries (NASTIES) as obstacles to investigating hominin evolutionary relationships in the Later Middle Paleolithic Levant. Quaternary International, 350, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.01.024.

Shennan, S. J. (1989). Archaeology as archaeology or as anthropology? Clarke’s Analytical Archaeology and the Binfords’ New perspectives in archaeology 21 years on. Antiquity, 63(241), 831–835.

Shennan, S. J. (1995). Diffusion revisited. In M. Kuna & N. Venclová (Eds.), Whither archaeology? Papers in honour of Evzen Neustupny (pp. 193–198). Praha: Institute of Archaeology.

Shennan, S. J. (2006). From cultural history to cultural evolution: an archaeological perspective on social information transmission. In J. C. K. Wells, S. Strickland, & K. N. Laland (Eds.), Social information transmission and human biology (pp. 173–190). London: CRC Press.

Sholts, S. B., Gingerich, J. A. M., Schlager, S., Stanford, D. J., & Wärmländer, S. K. T. S. (2017). Tracing social interactions in Pleistocene North America via 3D model analysis of stone tool asymmetry. PLoS One, 12(7), e0179933.

Shott, M. J. (1996). Innovation and selection in prehistory: a case study from the American Bottom. In G. H. Odell (Ed.), Stone tools: theoretical insights into human prehistory (pp. 279–309). New York: Plenum Press.

Siemaszko, J. (1999). Stone Age settlement in the Lega Valley microregion of north-east Poland. European Journal of Archaeology, 2(3), 293–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/146195719900200302.

Sinitsyna, G. (2002). Lyngby points in Eastern Europe. Archeologia Baltica, 5, 83–93.

Sinopoli, C. M. (1991). Style in arrows: a study of an ethnographic collection from the western United States. In P. T. Miracle, L. E. Fisher, & J. Brown (Eds.), Foragers in context (pp. 63–87). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Sommer, U. (2000). Archaeology and regional identity in Saxony. Public Archaeology, 1(2), 125–142.

Stodiek, U., & Paulsen, H. (1996). Mit dem Pfeil, dem Bogen...Technik der steinzeitlichen Jagd. Isensee: Oldenburg.

Straus, L. G. (2006). Of stones and bones: interpreting site function in the Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Western Europe. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 25(4), 500–509.

Sulgostowska, Z. (1989). O Podstawach Wydzielenia Kultury Perstunskiej (Na Marginesie Dwoch Prac Karola Szymczaka). Archeologia Polski, 34(2), 429–436.

Süß, E., & Thomann, E. (2009). Vorgeschichtliche Funde aus dem Landkreis Schwandorf. Nabburg: self-published.

Szymczak, K. (1984). Les Études Poursuivies Sur Le Paléolithique Final Dans La Partie Occidentale De La Plaine Balte-Orientale. Archaeologia Interregionalis, 1984, 105–120.

Szymczak, K. (1987). Perstunian culture—the eastern equivalent of the Lyngby culture in the Neman Basin. In J. M. Burdukiewicz & M. Kobusiewicz (Eds.), Late Glacial in central Europe: culture and environment (pp. 267–276). Wrocław: Polskiej Akademii Nauk.

Szymczak, K. (1999). Late Palaeolithic cultural units with tanged points in north eastern Poland. In S. K. Kozlowski, J. Gurba, & L. L. Zaliznyak (Eds.), Tanged point cultures in Europe. Read at the international archaeological symposium. Lublin, September, 13–16, 1993 (pp. 93–101). Lublin: Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press.

Szymczak, K. (1991). Odpowiedź na artykuł Zofii Sulgostowskiej "O podstawach wydzielania kultury perestuńskiej". Archeologia Polski, 35, 341-346.

Taute, W. (1963). Funde der spätpaläolithischen “Federmesser-Gruppen” aus dem Raum zwischen mittlerer Elbe und Weichsel. Berliner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, 3, 62–111.

Taute, W. (1968). Die Stielspitzen-Gruppen im nördlichen Mitteleuropa. Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der späten Altsteinzeit. Köln: Böhlau Verlag.

Taute, W. (1972). Die spätpaläolithisch-frühmesolithische Schichtenfolge im Zigeunerfels bei Sigmaringen (Vorbericht). Archäologische Informationen, 1, 29–40.

Tilley, C. (1998). Archaeology as socio-political action in the present. In D. S. Whitley (Ed.), Reader in archaeological theory: post-processual and cognitive approaches (pp. 305–330). London: Routledge.

Tomášková, S. (2003). Nationalism, local histories and the making of data in archaeology. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 9(3), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/3134599.

Tostevin, G. B. (2013). Seeing lithics: a middle-range theory for testing for cultural transmission in the Pleistocene (American school of prehistoric research monograph series). Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Trigger, B. G. (1989). A history of archaeological thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trölsch, O. (1976). Altsteinzeitliche Siedlungsplätze in der Umgebung von Mölln. Offa, 33, 5–42.

Valde-Nowak, P., Kraszewska, A., & Stefański, D. (2012). Arch-backed and tanged point technocomplexes in the North Carpathian zone. Recherches Archéologiques Nouvelle Serie, (5-6), 69–85.

Valoch, K. (1966). Spätpaläolithische Stationen in Raum von Bučovice in Mähren. Sbornik praci filosoficke fakulty brnenski university, 15(E11), 5–14.

Vasil’ev, S. (2001). The Final Palaeolithic in northern Asia: lithic assemblage diversity and explanatory models. Arctic Anthropology, 38(2), 3–30.

Veil, S. (1987). Ein Fundplatz der Stielspitzen-Gruppen ohne Stielspitzen bei Höfer, Ldkr. Celle. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 17, 311–322.

Vencl, S. (1966). Ostroměřská skupina: nová pozdně paleolitická skupina v Čechách. Archeologické rozhledy, 18, 309–137.

Vencl, S. (1970a). Das Spätpaläolithikum in Böhmen. L'Anthropologie, 8, 3–68.

Vencl, S. (1970b). Die böhmische Fazies der Federmesser-Gruppen. In H. Schwabedissen, R. Schütrumpf, & H. Schwabedissen (Eds.), Frühe Menschheit und Umwelt. Teil 1. Archäologische Beiträge (Vol. 1, pp. 375–381). Köln: Böhlau Verlag.

Vencl, S. (2013). The Late Palaeolithic. In S. Vencl (Ed.), The Palaeolithic and Mesolithic (pp. 117–138). Prag: Archeologický ústav AV ČR.

Vermeersch, P. M. (1977). Die stratigraphischen Probleme der postglazialen Kulturen in Dünengebieten. Quartär, 27(28), 103–109.

Weißmüller, W. (1995). Sesselfelsgrotte II. Die Silexartefakte der Unteren Schichten der Sesselfelsgrotte. Ein Beitrag zum Problem des Moustérien. Saarbrücken, Franz Steiner Verlag.

Werner, H., & Schönweiß, W. (1974). Eine epipaläolithische und mesolithische Wohnanlage von Sarching, Ldkr. Regensburg. Eine Fundstelle der “Atzenhofener Gruppe” im Donautal? Bonner Hefte zur Vorgeschichte, 8, 109–120.

Wiessner, P. W. (1985). Style or isochrestic variation? A reply to Sackett. American Antiquity, 50(1), 160–166.

Wobst, M. (1978). The archaeo-ethnology of hunter-gatherers or the tyranny of the ethnographic record in archaeology. American Antiquity, 43(2), 303–309.

Wyss, R. (1953). Beiträge zur Typologie der spätpaläolithisch- mesolithischen Übergangsformen. Basel.