Abstract

Purpose

Women who pursue fertility at an advanced age are increasingly common. Family planning and sexual education have traditionally focused on contraception and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. A focus should now also be placed on fertility awareness and fertility preservation. This manuscript aims to give an update on the existing evidence around elective oocyte cryopreservation, also highlighting the need for fertility education and evidence-based, individualized counselling.

Methods

A thorough electronic search was performed from the start of databases to March 2020 aiming to summarize the existing evidence around elective egg freezing, the logic behind its use, patient counselling and education, success rates and risks involved, regulation, cost-effectiveness, current status and future perspectives.

Results

Clinician-led counselling regarding reproductive aging and fertility preservation is often overlooked. Elective oocyte cryopreservation is not a guarantee of live birth, and the answer regarding cost-effectiveness needs to be individualized. The existing studies on obstetric and perinatal outcomes following the use of egg freezing are, until now, reassuring. Constant monitoring of short-term and long-term outcomes, uniform regulation and evidence-based, individualized counselling is of paramount importance.

Conclusions

Elective oocyte cryopreservation is one of the most controversial aspects of the world of assisted reproduction, and a lot of questions remain unanswered. However, women today do have this option which was not available in the past. Elective oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility decline should be incorporated in women’s reproductive options to ensure informed decisions and reproductive autonomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Family planning has changed as the role of the woman has evolved during the last few decades. Globally the average age when women have their first child has significantly increased [1, 2]. Higher education, career aspirations, financial reasons and changes in society and in human relationships have all contributed to this change [3, 4]. Delaying childbearing has, however, a significant detrimental impact on female reproductive potential leading to age-related fertility decline and subsequent infertility and is not always by choice. Involuntary childlessness confers significant psychological burden [5] which has even been compared to the emotional distress of cancer diagnosis [6].

The decline in female reproductive potential is inevitable and irreversible. Age confers a bi-exponential decline in the quantity of oocytes especially after the age of 37 [7]. Egg quality and chromosomal integrity of the resulting embryos are also affected after the age of 35. Advanced maternal age is the most important risk factor for early miscarriage [8] with age-related risk of miscarriage being 51% at 40–44 years of age and 93% after the age of 45 [9]. Success rates after one cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF) are reported around 30% for women below 35, but this percentage significantly declines after this age leaving almost no chance of live birth for women over the age of 45 who wish to use their own eggs. Options such as adoption or IVF with egg donation may not be acceptable to women who wish to have genetically linked offspring and could involve various barriers including age.

Here comes the role of fertility preservation. At the moment, elective oocyte cryopreservation is the main option for protection against age-related fertility decline for women wishing to have biological children. The logic behind its use is that the success rates with ‘younger’ oocytes are better than after IVF in advanced age, and contrary to using donor oocytes, it may allow women to have genetically related offspring at an age where natural conception would be unlikely. However, there is often lack of awareness in women of reproductive age around what this treatment actually involves, how they can access it, what it costs, the possible implications and the success rates [10]. Elective egg freezing is one of the most controversial aspects in the world of assisted reproductive technology (ART), receiving great scientific interest [11, 12] and public attention [13]. The debate starts from terminology and extends to the acceptance of this treatment which has been described both as ‘women’s emancipation’ and as ‘dangerous delusion’ [14, 15].

Aims and methods

Family planning and sexual education have traditionally focused on contraception and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. A focus should now also be placed on fertility awareness and fertility preservation as women who pursue fertility at an advanced age are increasingly common. This manuscript aims to give an update on the existing evidence around elective oocyte cryopreservation regarding success rates, risks, costs and benefits, current status and regulation of this treatment. It also highlights the need for fertility education and evidence-based, individualized counselling.

A thorough electronic search was performed in PubMed, Medline, Embase and Cinahl databases to provide an update on the existing evidence around elective egg freezing from the start of databases to August 2020. The search terms included fertility preservation OR egg freezing OR oocyte cryopreservation OR oocyte vitrification OR slow freezing AND success rates OR regulation OR ART OR fertility OR social egg freezing and combinations. Relevant results were identified, and their references were hand searched. The MESH terms used were ‘cryopreservation’, ‘oocytes’, ‘freezing’ and ‘vitrification’. The websites of regulatory authorities overseeing ART treatments in different countries were explored. References from selected studies were cross-checked, and meeting proceedings of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine were also searched.

A glimpse of the past

The first pregnancy (twin) from a frozen-thawed oocyte was reported in 1986 [16]. The slow freezing technique was used for years but without great success [17] until vitrification was introduced and the first live birth was reported [18]. The advantage of vitrification over slow freezing is that it offers an ‘instant’, rapid freezing from liquid to glass state without permitting the formation of ice crystals which could destroy the delicate oocyte. The success rates were improved with vitrification [19,20,21], which is not only the current cryopreservation technique of choice [22], but also less time-consuming and more cost-effective than traditional methods. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is used to overcome the hardening of the zona pellucida following cryopreservation [23] and results in fertilization rates of 70–80% [24]. Even though cryopreservation impacts on the meiotic spindle essentially causing its destruction, this is reversed within a few hours after thawing, and embryo chromosomal abnormalities are not increased [25,26,27]. The technique appears to be safe and to double success rates [28]. Oocyte survival rates from the freezing-thawing process are reported as higher than 90% on average [29] leading to a sharp increase in the popularity of egg freezing.

In 2004, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) taskforce on Ethics and Law [30] looked into ethical considerations and reasons for gamete cryopreservation—preserving fertility after cancer, chronic illness, iatrogenic complications of treatment or simply with advancing age. In 2013, it was recognized that success rates with oocyte cryopreservation were as good as with fresh oocytes, and the experimental label on the technique was lifted with an ASRM (American Society for Reproductive Medicine) statement, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology also updated the guidance on fertility preservation [31, 32]. It was, however, highlighted that there was not enough evidence to support oocyte cryopreservation for the sole purpose of circumventing reproductive aging. Despite this statement, more than half the fertility units in the USA were already offering oocyte cryopreservation at the time, and most of them were also promoting it for non-medical reasons [33]. Thus, in 2014, in the reproductive facts section of the ASRM website, the idea of using oocyte cryopreservation without a medical indication was introduced, and relevant advice was offered. At the same time, the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society released a position statement on egg freezing as an ‘option for women wishing to preserve their fertility in the face of anticipated decline’ [24]. Instead of thinking of oocyte cryopreservation as a ‘social’, ‘non-medically indicated’, lifestyle form of ART, Stoop et al. introduced the term ‘oocyte banking for anticipated gamete exhaustion’ introducing it as a preventative measure against future age-related infertility [34], while the ESHRE Taskforce for Ethics and Law used the term ‘oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility loss’ [35].

Current status

Egg preservation cycles have been documented as the fastest growing fertility treatment in the UK, increasing by 10% per year. There was a 240% increase from 2013 to 2018. In Spain, egg freezing cycles for fertility preservation increased from 4% of total vitrification procedures to 22% in a 10-year period, as reported by a retrospective, observational multicenter study [36]. Similarly, in the USA, fertility preservation cycles increased from 9607 in 2017 to 13,275 in 2018 [37]. Developing countries are following similar trends [38].

Surveys on women choosing elective fertility preservation reveal that the vast majority proceed with egg freezing due to lack of a suitable partner [39,40,41,42]. While women in their 20s or early 30s consider that their career aspirations would be a reason to consider egg freezing [43, 44], for the majority of surveyed women who did freeze their eggs, their career was ‘not at all’ a factor which influenced their decision [41]. While career aspirations and financial parameters including childcare support or maternity leave can somehow be managed, finding the right partner is outside one’s control and can carry social stigma [45]. Avoiding ‘panic partnering’ and future feelings of blame and guilt are amongst women’s incentives when considering fertility preservation [46]. Also, a percentage of patients who seek ovarian cryopreservation consider it protective against future medical issues that might be fertility impairing [39].

Evidence suggests that following egg freezing, very few patients regret their decision, and the majority of patients perceive the experience as empowering and would recommend it to others [40, 41, 47, 48]. A single US study reported that 49% of patients experienced mild/moderate regret which, however, seems to be associated with the information and emotional support received during the decision process and with perceived chances of live birth [49]. The most recent study concluded that 91% of patients reported no regret even if pregnancy was achieved without having to use the stored oocytes [41]. Half of the patients surveyed in this study had conceived naturally.

-

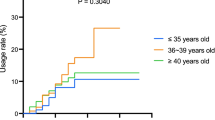

Fertility awareness

Several studies demonstrate a lack of awareness on how age impacts fertility for women [40, 43, 50,51,52]. For fertility preservation, the main prognostic factor for success rates is the age at egg freezing. The best results are achieved if eggs are cryopreserved before 36 years of age according to a meta-analysis [53]. A woman wishing to become pregnant in her 40s with her own fresh eggs has a 6.6% estimated success rate, but if she had frozen her eggs at the age of 30, the success rate would jump to > 40% per transfer [15]. However, most patients proceed with cryopreservation at the age of 36–39, with the mean age at the time of freezing being 37–38 and 80% of patients being above 35 [39,40,41, 54,55,56]. It is worth mentioning that the majority of surveyed women who had egg freezing wish they had done it earlier on, and only a minority received information regarding this treatment from their gynaecologist [40, 47]. Interestingly 42% of surveyed women who had elective egg freezing underestimated their chances of having a livebirth [41].

A US study on the attitudes of obstetric and gynaecology residents revealed that while the majority felt that age-related fertility decline should be discussed with patients at routine visits, most would not support the option of elective oocyte cryopreservation. Also, nearly half underestimated the effect of age on fertility, and 78.4% overestimated ART success rates [57]. Similarly, a survey including 5000 ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) members concluded that due to limited consultation time and lack of knowledge, less than one-third of clinicians counsel patients regarding reproductive aging and fertility reservation [58]. Reproductive-aged women often resort to online sources to get information, and physicians are not exempt; they are also influenced by information found online including social media [59, 60]. Health professionals, from all specialties and from various stages of training, due to work demands are possibly more likely to postpone parenthood, hence good candidates for fertility preservation. However, a recent study showed that the majority of surveyed childless physicians of reproductive age had lack of knowledge regarding ART and fertility preservation options and expressed regret about not proceeding with fertility preservation in the past [61]. A Polish survey commented that 46% of women treated for infertility considered online forums their main source of information on fertility treatment and a third of the patients had received more information online than from their medical team [62]. Sixty-four percent of patients consulted online sources before going ahead with treatment. A study on 21 websites providing information on elective egg freezing concluded that most websites are transparent regarding authors, affiliations and sponsorships but do not always represent an accurate source of information or the information is not easily readable for the public [63].

-

Success rates

Reported success rates vary between different centres, and the capabilities of the technique are often ‘oversold’ or underestimated [64]. The results of a systematic review and meta-analysis are awaited [65]. Most evidence is based on egg freezing cycles for egg donation or for medical reasons, and data cannot always be extrapolated to women who seek elective fertility preservation. Although success rates have improved with the introduction of vitrification, in around four in five cases, the egg freezing treatment is unsuccessful according to 2017 HFEA (Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority) data [66].

The age at the time of freezing and the number of stored oocytes are the key factors that determine outcomes [67,68,69]. It is estimated that on average, 20 oocytes are required to achieve a pregnancy with the minimum proposed number being eight to ten [67, 68, 70]. However, for a given age, success rates will reach a plateau which cannot be surpassed regardless of oocyte number. Data from a multicenter retrospective study in Spain, the largest series to date, yielded interesting results [36]. The cumulative probability of live birth rate in the most optimistic scenario was reported as high as 94.4%, but this was limited for women who electively froze their eggs at 35 years of age or younger with 24 oocytes in storage. For 10 oocytes in storage, the cumulative live birth rate in this age group was 42.8%. For women who cryopreserved oocytes at an older age, the success rate was markedly lower reaching 5.9% for 5 oocytes and 17.3% for 8 oocytes. This means that one cycle may not be enough, but women are often willing to undergo multiple cycles to achieve a sufficient number of oocytes to be stored [71]. These data clearly suggest that age is the main factor that dictates success rates, and even with the most optimistic predictions, a live birth cannot be guaranteed.

Doyle et al. (2016) introduced ‘vitrified oocyte to live-born child efficiency’ to describe the ability of a frozen-thawed oocyte to result in live birth as a tool to guide decision-making regarding success rates and to indicate the number of oocytes (and therefore cycles) needed [69]. The authors suggest that this model may allow accurate estimations of the chance of having 1–3 children based on age at the time of egg freezing and the number of oocytes retrieved. It was estimated that 15–20 stored mature eggs were required for women younger than 38 for a 75% chance of having one child, whereas in the age group 38–40, 25–30 oocytes were needed for a 70% chance. Women above 42 would need 61 eggs to achieve such success rates. Although less efficient for women above 40, there was still a maximum 50% chance of a live birth with 30 stored oocytes (which would be challenging to achieve at this age group). Similarly, in another approach, Goldman et al. (2017) extrapolating data from ICSI cycles attempted to develop a user-friendly counselling tool to predict how many cycles would be needed and the probability of a woman having at least one, two or three live birth(s) [72]. These evidence-based tools can be adjusted taking into consideration parameters both related to patient characteristics and the unit’s expertise.

-

Cost-effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness of elective oocyte cryopreservation is also controversial. Some studies conclude that since stored gametes may never need to be used, egg freezing may not be cost-effective compared to trying naturally or resort to standard IVF if needed [73, 74]. When freezing eggs at a young age such as in their 20s or early 30s, women may achieve better success rates but are more likely to pay more for storage and to conceive naturally as they have many reproductive years ahead. Thus, they may undergo the physical and emotional stress of treatment for no reason [75]. However, when freezing eggs at an advanced age, women may need more cycles and more oocytes in order to achieve comparable or worse success rates. In a large published series, the percentage of women returning to use their cryopreserved oocytes was only 12.1% [36].

Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that, depending on age, egg freezing could represent better ‘value for money’ compared to conventional IVF [76, 77]. The authors conclude that it is cost-effective to freeze eggs up to the age of 37. This age may be best in terms of cost-effectiveness with a cost of $28,759 per additional live birth. The highest live birth rates are documented for ages below 34, but egg freezing still improved success rates up to the age of 40 [77, 78]. Freezing 16 eggs at age 35 reduced the cost per live birth by 27% while also increasing by almost 20% the odds of live birth. For women wishing to defer pregnancy until the age of 40, a lower overall cost per live birth was documented if they resorted to egg freezing before the age of 38 [77]. Since multiple factors are involved, maybe the answer regarding cost-efficiency should not be seen as a mathematical, common approach to all but should rather be tailored to the woman’s personal circumstances and characteristics. Response to stimulation, ovarian reserve and the number of children the woman wishes to have all matter in her decision-making [55]. Egg freezing has also been seen as an insurance policy. Using a parallel with health insurance, people set this up although the ideal scenario is not needing to use it [15]. It is important to note that existing data on the number of women returning to use their stored oocytes are preliminary since more women may return in the future.

-

Regulation and funding

Uniform regulation regarding ART treatment is lacking even amongst European countries and sometimes within the same country [79]. This is not surprising as there are differences in terms of social, cultural and religious beliefs as well as the economic status and healthcare services. While most countries have relevant legislation, substantial heterogeneity is documented. Acceptance and regulation of the technique significantly differ amongst different countries. Existing differences in costs, legislation and storage limits, often result in fertility tourism.

According to the most recent ESHRE data, medically indicated fertility preservation is allowed in all 43 surveyed countries, but elective oocyte freezing is not permitted in Austria, France, Hungary, Lithuania, Malta, Norway, Serbia and Slovenia and is also not performed in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Moldova despite the absence of legislation that outlaws the technique [79]. While egg freezing cycles are increasing in Europe, few countries collect data regarding treatment details and outcomes [80].

The time limit for storage varies between different countries and often can only be extended for medical reasons. The 10-year storage limit in the UK has been heavily criticized. Due to this policy, women may get the false impression that they should freeze their eggs at an age when the results would be inferior [81]. Their other options would be to prematurely decide to have their eggs fertilized for further storage of embryos or to transfer their stored oocytes to other countries. Not being able to store eggs for more than 10 years comes as a paradox since women are allowed to use donor eggs up to the age of 50. As it has been previously highlighted by other authors, there should be no reason to deny women treatment with their own eggs at a similar age [82]. In July 2020, the UK storage limit for frozen eggs, sperm and embryos was extended by two years in view of the Covid-19 pandemic.

There are often various socioeconomic and cultural reasons that lead to postponing parenthood, which are possibly linked to the decision to proceed with fertility preservation [83]. However, elective egg freezing is not funded by the state in any country to our knowledge. This creates inequalities in access to treatment and leads to ethically ambiguous commercial initiatives. For instance, women can be encouraged to donate eggs and receive free treatment in return. Also, several companies promote and sponsor egg freezing for their employees. This is considered as an insurance policy for working women allowing them to focus on career without having to think of the ticking clock of reproduction and may be improving gender work place equality while at the same time serving the company’s interests [84]. However, this initiative has been regarded with scepticism [85, 86]. Is the hidden promise valid that delaying motherhood for the sake of success in the workplace will not have a toll on fertility through fertility preservation? Will women feel obliged to use this technology just because it is offered or because there is a stigma in the workplace against women who choose to reproduce earlier in their careers? Or will they feel obliged to continue working in this company in return? Women (or their employers) who can afford it may achieve a boost in their reproductive life span when others cannot. For those who cannot afford this, is it fair to depend on egg freezing share schemes or to their employer in order to preserve their fertility?

A word of caution

Egg freezing is neither a guarantee of a live birth nor a panacea for the various socioeconomic, cultural and emotional challenges which may lead women to defer parenthood [83]. Also, it comes with the risks of any IVF treatment. Immediate risks related to ovarian stimulation and egg collection such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, bleeding, infection or anaesthetic complications are reported below 1% [87].

Since vitrification is amongst the new advancements in ART, there are no long-term follow-up studies, and most evidence consists of retrospective studies and case reports [88]. There is some evidence demonstrating the differential impact of both slow freezing and vitrification on the gene expression profile of human frozen-thawed oocytes compared to non-cryopreserved controls [89]. The time in storage does not seem to affect the cycle outcome for either cryopreservation technique [29, 90, 91]. A retrospective cohort study [92] comparing outcomes of more than a thousand babies born from vitrified oocytes versus fresh oocytes suggested that oocyte vitrification does not increase adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes nor congenital anomalies and complimented similar findings from previous smaller studies [28, 93, 94]. Of note, the proportion of female offspring was significantly higher in the vitrification group (53.8% vs. 47.4%). An observational study looked at outcomes following ART using frozen-thawed oocytes versus fresh oocytes in the same group of patients. Interestingly, 63 couples in this study had live births from both fresh and frozen oocytes with no significant differences in any of the investigated outcomes [95]. Outcomes should be monitored closely, and follow-up of the offspring should be warranted as for every technique which is not time tested [96]. Emphasis should be given in the long-term follow-up of the offspring to detect late manifestations of possible DNA damage including transgenerational effects.

The progress in ART technology has been rapid, often outstripping the speed of ethical debate. There is plethora of literature around the ethical aspects of fertility preservation. Elective egg freezing may provide women with false security. This sense of reproductive security could push the limits of childbearing age and could result in pregnancies not only in the 40s or early 50s but also in the 60s or 70s. Advanced maternal age is a recognized risk factor for various pregnancy complications, but women seem prepared to accept these risks [41]. Furthermore, the offspring will grow into a family where the mother is significantly older than the social norm, and this may create issues of adjustment. The number of single parent families by choice will possibly increase. However, these issues are shared with traditional IVF and egg donation [97], most countries have regulation regarding age limits in fertility treatment and current research does not suggest that women who proceed with elective fertility preservation have extreme reproductive goals. A retrospective cohort study, exploring attitudes and reproductive choices for women proceeding with fertility preservation, documented that the maximum age of parenthood they considered acceptable was below 44 years [47]. The results of another retrospective study on 1468 women who had elective egg freezing demonstrated that the 137 patients who returned to use their stored eggs did so, on average, at 2 years of storage, at an average age of 39.2 years [67, 68].

Since elective egg freezing is only possible in the private setting, commercialization is unavoidable [98], and clever promotion campaigns and media often create false hopes [99, 100]. Since there is no uniform reporting system, the information provided by websites and brochures may be selective. A study looking into IVF center websites found that performance was reported in 51 different ways [101]. Women should look into the clinics’ success rates for their own age group and should ask for live birth rates. It is important to know how much experience the unit has in vitrification and how many women came back to use their frozen eggs. Since more than one cycle may be required to achieve sufficient numbers, fertility units have created offer packages to cover the cost of the stimulation cycles and storage. However, maybe women should consider storing eggs in different units to eliminate unpredictable factors (not ‘putting all one’s eggs in one basket’ as per media cover titles).

The role of individualized counselling should be highlighted [102] in the context of a fertility team including clinicians, nurses and psychologists. Emotional support is a key especially since contrary to what happens in conventional IVF, women seeking egg freezing are most likely to go through this process alone. The fate of the stored oocytes in case these are not used or in case of illness or death and other unforeseen factors, such as possible human errors, unpaid storage fees, destruction or even theft, should also be touched on in the discussion, and decisions should be documented [103]. Age-specific success rates are also dependent on the number of oocytes stored; therefore, counselling should explain the possible need for multiple stimulation cycles [87].

Future perspectives

For women who want children, fertility education is key. Natural conception or donor insemination is the preferred way, and couples who have decided to have children should start trying early. For those, though, that conventional family planning is not possible due to various reasons, the chance for motherhood should not be denied, and they should be encouraged to be proactive to prevent infertility [104]. The aim should be to increase awareness amongst women of reproductive age regarding age-related fertility decline. Funding strategies could potentially be developed in the future to prevent infertility as preventative medicine has been developed in so many other fields. Also, algorithms could be developed to individually assess fertility status and cultivate a pro-fertility mentality in a realistic context [105]. The Fertility Assessment and Counseling Clinic in Denmark is a good example of such strategy offering tailored counselling with the aim to predict and protect fertility [106]. Half the women who attended this clinic wished to explore ways to preserve or optimize fertility, and 70% wanted to be informed regarding how long they could safely postpone childbearing. The vast majority found this counselling useful, and 35% changed their decision to delay pregnancy.

There are multiple roads to parenthood, but at the moment, fertility preservation is the main approach to age-related fertility decline for women who want to have genetically related offspring. This may change in the near future since scientific developments never cease. Stem cell research is promising and rapidly evolving [107]. Somatic cells such as skin cells may be reprogrammed to serve as functional gametes [108]. Also, as our understanding increases in demystifying the physiology of reproduction and stem cells are identified within the ovary, perhaps there will even be the possibility to pause the ovarian biological clock and prevent follicle atresia [109,110,111].

Should we, as a society, be moving towards making egg freezing a common procedure? Should the gift to our daughters’ graduation be fertility preservation? Many questions around fertility preservation still remain unanswered, and more well-designed studies are needed before reaching sound conclusions. However, women today do have this option which was not available in the past. Elective egg freezing should not be seen as a means to intentionally delay parenthood but rather as a preventative measure to preserve fertility. Fertility preservation should be included in the discussion around reproductive options in order to ensure informed decisions.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

US National Centre for Health Statistics, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/births.htm, 2018. Accessed June 2020.

European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20190318-1. Accessed June 2020.

Mills M, Rindfuss RR, McDonald P, te Velde E, Reproduction obotE, Force ST. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:848–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr026.

Inhorn MC, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Birger J, Westphal LM, Doyle J, Gleicher N, et al. Elective egg freezing and its underlying socio-demography: a binational analysis with global implications. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-018-0389-z.

Cil AP, Turkgeldi L, Seli E. Oocyte cryopreservation as a preventive measure for age-related fertility loss. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33:429–35. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1567819.

Domar AD, Zuttermeister PC, Friedman R. The psychological impact of infertility: a comparison with patients with other medical conditions. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;14(Suppl):45–52.

Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, Richardson SJ, Nelson JF. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 1992;7:1342–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570.

Hook EB. Rates of chromosome abnormalities at different maternal ages. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:282–5.

Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, Olsen J, Melbye M. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2000;320:1708–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708.

Milman LW, Senapati S, Sammel MD, Cameron KD, Gracia C. Assessing reproductive choices of women and the likelihood of oocyte cryopreservation in the era of elective oocyte freezing. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1214–22.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.010.

Stoop D, Cobo A, Silber S. Fertility preservation for age-related fertility decline. Lancet (London, England). 2014;384:1311–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61261-7.

Garcia-Velasco JA, Domingo J, Cobo A, Martínez M, Carmona L, Pellicer A. Five years’ experience using oocyte vitrification to preserve fertility for medical and nonmedical indications. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1994–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.004.

Jones BP, Serhal P, Ben-Nagi J. Social egg freezing should be offered to single women approaching their late thirties: FOR: women should not suffer involuntary childlessness because they have not yet found a partner. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;125:1579. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15291.

Homburg R, van der Veen F, Silber SJ. Oocyte vitrification--women's emancipation set in stone. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1319–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.127.

Lockwood GM. Social egg freezing: the prospect of reproductive ‘immortality’ or a dangerous delusion? Reprod BioMed Online. 2011;23:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.05.010.

Chen C. Pregnancy after human oocyte cryopreservation. Lancet (London, England). 1986;1:884–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90989-x.

Bernard A, Fuller B. Cryopreservation of human oocytes: a review of current problems and perspectives. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2:193–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/2.3.193.

Kuleshova L, Gianaroli L, Magli C, Ferraretti A, Trounson A. Birth following vitrification of a small number of human oocytes: case report. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 1999;14:3077–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.12.3077.

Antinori M, Licata E, Dani G, Cerusico F, Versaci C, Antinori S. Cryotop vitrification of human oocytes results in high survival rate and healthy deliveries. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;14:72–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60766-3.

Fadini R, Brambillasca F, Renzini MM, Merola M, Comi R, De Ponti E, et al. Human oocyte cryopreservation: comparison between slow and ultrarapid methods. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;19:171–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60069-7.

Rienzi L, Romano S, Albricci L, Maggiulli R, Capalbo A, Baroni E, et al. Embryo development of fresh ‘versus’ vitrified metaphase II oocytes after ICSI: a prospective randomized sibling-oocyte study. Hum Reprod. 2009;25:66–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dep346.

Rienzi L, Gracia C, Maggiulli R, LaBarbera AR, Kaser DJ, Ubaldi FM, et al. Oocyte, embryo and blastocyst cryopreservation in ART: systematic review and meta-analysis comparing slow-freezing versus vitrification to produce evidence for the development of global guidance. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:139–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw038.

Kazem R, Thompson LA, Srikantharajah A, Laing MA, Hamilton MP, Templeton A. Cryopreservation of human oocytes and fertilization by two techniques: in-vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 1995;10:2650–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135761.

Saumet J, Petropanagos A, Buzaglo K, McMahon E, Warraich G, Mahutte N. No. 356-egg freezing for age-related fertility decline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:356–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.004.

Cobo A, Rubio C, Gerli S, Ruiz A, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization to assess the chromosomal status of embryos obtained from cryopreserved oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:354–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01725-8.

Rienzi L, Martinez F, Ubaldi F, Minasi MG, Iacobelli M, Tesarik J, et al. Polscope analysis of meiotic spindle changes in living metaphase II human oocytes during the freezing and thawing procedures. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2004;19:655–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh101.

Cobo A, Pérez S, De los Santos MJ, Zulategui J, Domingo J, Remohí J. Effect of different cryopreservation protocols on the metaphase II spindle in human oocytes. Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;17:350–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60218-0.

Noyes N, Porcu E, Borini A. Over 900 oocyte cryopreservation babies born with no apparent increase in congenital anomalies. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;18:769–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60025-9.

Cobo A, Garrido N, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Six years’ experience in ovum donation using vitrified oocytes: report of cumulative outcomes, impact of storage time, and development of a predictive model for oocyte survival rate. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1426–34.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.020.

Taskforce 7: Ethical considerations for the cryopreservation of gametes and reproductive tissues for self use. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2004;19:460–2;https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deh051

Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:37–43;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.028

Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2500–10. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.49.2678.

Rudick B, Opper N, Paulson R, Bendikson K, Chung K. The status of oocyte cryopreservation in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2642–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.079.

Stoop D, van der Veen F, Deneyer M, Nekkebroeck J, Tournaye H. Oocyte banking for anticipated gamete exhaustion (AGE) is a preventive intervention, neither social nor nonmedical. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28:548–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.01.007.

Dondorp W, de Wert G, Pennings G, Shenfield F, Devroey P, Tarlatzis B, et al. Oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility loss. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27:1231–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des029.

Cobo A, García-Velasco J, Domingo J, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Elective and onco-fertility preservation: factors related to IVF outcomes. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:2222–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey321.

American Society of Reproductive Medicine ASfR. https://www.asrm.org/news-and-publications/news-and-research/press-releases-and-bulletins/more-than-74-thousand-babies-born-from-assisted-reproductive-technology-cycles-done-in-2018%2D%2Drecord-90-of-babies-born-from-art-aresingletons/#:~:text=Fertility%20preservation%20cycles%20for%20patients,2017%20and%208%2C825%20in%202016. 2020. Accessed Jun 2020

Allahbadia GN. Social egg freezing: developing countries are not exempt. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66:213–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0803-9.

Baldwin K, Culley L, Hudson N, Mitchell H, Lavery S. Oocyte cryopreservation for social reasons: demographic profile and disposal intentions of UK users. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;31:239–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.04.010.

Hodes-Wertz B, Druckenmiller S, Smith M, Noyes N. What do reproductive-age women who undergo oocyte cryopreservation think about the process as a means to preserve fertility? Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1343–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.201.

Jones BP, Kasaven L, L'Heveder A, Jalmbrant M, Green J, Makki M, et al. Perceptions, outcomes, and regret following social egg freezing in the UK; a cross-sectional survey. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:324–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13763.

Inhorn MC, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Westphal LM, Doyle J, Gleicher N, Meirow D, et al. Ten pathways to elective egg freezing: a binational analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:2003–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1277-3.

Tozzo P, Fassina A, Nespeca P, Spigarolo G, Caenazzo L. Understanding social oocyte freezing in Italy: a scoping survey on university female students’ awareness and attitudes. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2019;15:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40504-019-0092-7.

Mahesan AM, Sadek S, Ramadan H, Bocca S, Paul ABM, Stadtmauer L. Knowledge and attitudes regarding elective oocyte cryopreservation in undergraduate and medical students. Fertil Res Pract. 2019;5(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40738-019-0057-9.

Baldwin K, Culley L. Women’s experience of social egg freezing: perceptions of success, risks, and ‘going it alone’. Hum Fertil. 2018:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647273.2018.1522456.

Baldwin K, Culley L, Hudson N, Mitchell H. Running out of time: exploring women’s motivations for social egg freezing. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2019;40:166–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2018.1460352.

Stoop D, Maes E, Polyzos NP, Verheyen G, Tournaye H, Nekkebroeck J. Does oocyte banking for anticipated gamete exhaustion influence future relational and reproductive choices? A follow-up of bankers and non-bankers. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015;30:338–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu317.

Wafi A, Nekkebroeck J, Blockeel C, De Munck N, Tournaye H, De Vos M. A follow-up survey on the reproductive intentions and experiences of women undergoing planned oocyte cryopreservation. Reprod BioMed Online. 2020;40:207–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.11.010.

Greenwood EA, Pasch LA, Hastie J, Cedars MI, Huddleston HG. To freeze or not to freeze: decision regret and satisfaction following elective oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:1097–104.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.02.127.

Daniluk JC, Koert E, Cheung A. Childless women’s knowledge of fertility and assisted human reproduction: identifying the gaps. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:420–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.046.

Lampic C, Svanberg AS, Karlström P, Tydén T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2006;21:558–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dei367.

Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Tucker L, Lampic C. Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27:1375–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des011.

Cil AP, Bang H, Oktay K. Age-specific probability of live birth with oocyte cryopreservation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:492–9.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.023.

Vallejo V, Lee J, Schuman L, Witkin G, Cervantes E, Sandler B, et al. Social and psychological assessment of women undergoing elective oocyte cryopreservation: a 7-year analysis. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;03. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojog.2013.31001.

Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, Pritchard N, Hickey M, Peate M, McBain J, et al. Reproductive experiences of women who cryopreserved oocytes for non-medical reasons. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2017;32:575–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew342.

Gürtin ZB, Morgan L, O'Rourke D, Wang J, Ahuja K. For whom the egg thaws: insights from an analysis of 10 years of frozen egg thaw data from two UK clinics, 2008–2017. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:1069–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01429-6.

Yu L, Peterson B, Inhorn MC, Boehm JK, Patrizio P. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions toward fertility awareness and oocyte cryopreservation among obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2016;31:403–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev308.

Fritz R, Klugman S, Lieman H, Schulkin J, Taouk L, Castleberry N, et al. Counseling patients on reproductive aging and elective fertility preservation-a survey of obstetricians and gynecologists’ experience, approach, and knowledge. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:1613–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1273-7.

Romano M, Gesualdo F, Pandolfi E, Tozzi AE, Ugazio AG. Use of the internet by Italian pediatricians: habits, impact on clinical practice and expectations. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-23.

Galiatsatos P, Porto-Carreiro F, Hayashi J, Zakaria S, Christmas C. The use of social media to supplement resident medical education - the SMART-ME initiative. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:29332. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.29332.

Nasab S, Shah JS, Nurudeen K, Jooya ND, Abdallah ME, Sibai BM. Physicians’ attitudes towards using elective oocyte cryopreservation to accommodate the demands of their career. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36:1935–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01541-7.

Talarczyk J, Hauke J, Poniewaz M, Serdyńska-Szuster M, Pawelczyk L, Jedrzejczak P. Internet as a source of information about infertility among infertile patients. Ginekol Pol. 2012;83:250–4.

Shao YH, Tulandi T, Abenhaim HA. Evaluating the quality and reliability of online information on social fertility preservation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42:561–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.10.029.

Lockwood G, Fauser BCJM. Social egg freezing: who chooses and who uses? Reprod BioMed Online. 2018;37:383–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.08.003.

Wang A, Kumsa FA, Kaan I, Li Z, Sullivan E, Farquhar CM. Effectiveness of social egg freezing: protocol for systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030700.

Authority HFEA. Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, https://www.hfea.gov.uk/media/2894/fertility-treatment-2017-trends-and-figures-may-2019.pdf (accessed June 2020).

Society BF. British Fertility Society Press Office, https://www.britishfertilitysociety.org.uk/press-release/data-show-that-freezing-your-eggs-now-is-no-guarantee-of-a-baby-later/ (accessed May 2020).

Cobo A, García-Velasco JA, Coello A, Domingo J, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Oocyte vitrification as an efficient option for elective fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:755–64.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.027.

Doyle JO, Richter KS, Lim J, Stillman RJ, Graham JR, Tucker MJ. Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:459–66.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.026.

Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Fertility preservation in women. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:735–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.205.

Nekkebroeck J, Stoop D, Devroey P. A preliminary profile of women opting for oocyte cryopreservation for non-medical reasons. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2010;25:i15-i6.

Goldman RH, Racowsky C, Farland LV, Munné S, Ribustello L, Fox JH. Predicting the likelihood of live birth for elective oocyte cryopreservation: a counseling tool for physicians and patients. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2017;32:853–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dex008.

Klüber CM, Greene BH, Wagner U, Ziller V. Cost-effectiveness of social oocyte freezing in Germany: estimates based on a Markov model. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:823–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05449-x.

Hirshfeld-Cytron J, Grobman WA, Milad MP. Fertility preservation for social indications: a cost-based decision analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:665–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.029.

Jones BP, Serhal P, Ben NJ. Social egg freezing: early is not always best. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:1531. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13467.

van Loendersloot LL, Moolenaar LM, Mol BW, Repping S, van der Veen F, Goddijn M. Expanding reproductive lifespan: a cost-effectiveness study on oocyte freezing. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2011;26:3054–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der284.

Devine K, Mumford SL, Goldman KN, Hodes-Wertz B, Druckenmiller S, Propst AM, et al. Baby budgeting: oocyte cryopreservation in women delaying reproduction can reduce cost per live birth. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1446–53.e1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.029.

Mesen TB, Mersereau JE, Kane JB, Steiner AZ. Optimal timing for elective egg freezing. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1551–6.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.002.

Calhaz-Jorge C, De Geyter C, Kupka MS, Wyns C, Mocanu E, Motrenko T, et al. Survey on ART and IUI: legislation, regulation, funding and registries in European countries: The European IVF-monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoz044.

Shenfield F, de Mouzon J, Scaravelli G, Kupka M, Ferraretti AP, Prados FJ, et al. Oocyte and ovarian tissue cryopreservation in European countries: statutory background, practice, storage and use†. Hum Reprod Open. 2017:2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hox003.

Anderson R, Davies M, Lavery S. Obstetricians tRCo, Gynaecologists. Elective egg freezing for non-medical reasons. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol.n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16025.

Sauer MV, Kavic SM. Oocyte and embryo donation 2006: reviewing two decades of innovation and controversy. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;12:153–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60855-3.

Bozzaro C. Is egg freezing a good response to socioeconomic and cultural factors that lead women to postpone motherhood? Reprod BioMed Online. 2018;36:594–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.01.018.

Wiesing U. Egg freezing: a new medical technology and the challenges of modernity. Bioethics. 2019;33:538–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12625.

Baylis F. Left out in the cold: arguments against non-medical oocyte cryopreservation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:64–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30365-0.

Browne J. Technology, fertility and public policy: a structural perspective on human egg freezing and gender equality. Soc Polit Int Stud Gend State Soc. 2018;25:149–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxx022.

Fritz R, Jindal S. Reproductive aging and elective fertility preservation. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-018-0438-4.

Kopeika J, Thornhill A, Khalaf Y. The effect of cryopreservation on the genome of gametes and embryos: principles of cryobiology and critical appraisal of the evidence. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:209–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmu063.

Monzo C, Haouzi D, Roman K, Assou S, Dechaud H, Hamamah S. Slow freezing and vitrification differentially modify the gene expression profile of human metaphase II oocytes. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2012;27:2160–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des153.

Stigliani S, Moretti S, Anserini P, Casciano I, Venturini PL, Scaruffi P. Storage time does not modify the gene expression profile of cryopreserved human metaphase II oocytes. Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015;30:2519–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev232.

Parmegiani L, Garello C, Granella F, Guidetti D, Bernardi S, Cognigni GE, et al. Long-term cryostorage does not adversely affect the outcome of oocyte thawing cycles. Reprod BioMed Online. 2009;19:374–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60171-x.

Cobo A, Serra V, Garrido N, Olmo I, Pellicer A, Remohí J. Obstetric and perinatal outcome of babies born from vitrified oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1006–15.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.019.

Chian RC, Huang JY, Tan SL, Lucena E, Saa A, Rojas A, et al. Obstetric and perinatal outcome in 200 infants conceived from vitrified oocytes. Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;16:608–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60471-3.

Ho JR, Woo I, Louie K, Salem W, Jabara SI, Bendikson KA, et al. A comparison of live birth rates and perinatal outcomes between cryopreserved oocytes and cryopreserved embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:1359–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-0995-2.

Levi Setti PE, Albani E, Morenghi E, Morreale G, Delle Piane L, Scaravelli G, et al. Comparative analysis of fetal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancies from fresh and cryopreserved/thawed oocytes in the same group of patients. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.038.

Argyle CE, Harper JC, Davies MC. Oocyte cryopreservation: where are we now? Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:440–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw007.

Goold I, Savulescu J. In favour of freezing eggs for non-medical reasons. Bioethics. 2009;23:47–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00679.x.

van de Wiel L. The speculative turn in IVF: egg freezing and the financialization of fertility. New Genet Soc. 2020;39:306–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2019.1709430.

Barbey C. Evidence of biased advertising in the case of social egg freezing. New Bioeth. 2017;23:195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/20502877.2017.1396033.

Campo-Engelstein L, Aziz R, Darivemula S, Raffaele J, Bhatia R, Parker WM. Freezing fertility or freezing false hope? A content analysis of social egg freezing in U.S. print media. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2018;9:181–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2018.1509153.

Wilkinson J, Vail A, Roberts SA. Direct-to-consumer advertising of success rates for medically assisted reproduction: a review of national clinic websites. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012218. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012218.

Petropanagos A, Cattapan A, Baylis F, Leader A. Social egg freezing: risk, benefits and other considerations. CMAJ. 2015;187:666–9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141605.

Mintziori G, Veneti S, Kolibianakis EM, Grimbizis GF, Goulis DG. Egg freezing and late motherhood. Maturitas. 2019;125:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.017.

Mertes H, Pennings G. Social egg freezing: for better, not for worse. Reprod BioMed Online. 2011;23:824–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.09.010.

Hvidman HW, Petersen KB, Larsen EC, Macklon KT, Pinborg A, Nyboe AA. Individual fertility assessment and pro-fertility counselling; should this be offered to women and men of reproductive age? Hum Reprod. 2015;30:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu305.

Hvidman HW, Petersen KB, Larsen EC, Macklon KT, Pinborg A, Nyboe AA. Individual fertility assessment and pro-fertility counselling; should this be offered to women and men of reproductive age? Hum Reprod (Oxford, England). 2015;30:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu305.

Moreno I, Míguez-Forjan JM, Simón C. Artificial gametes from stem cells. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2015;42:33–44. https://doi.org/10.5653/cerm.2015.42.2.33.

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019.

Xiao G-Y, Liu IH, Cheng C-C, Chang C-C, Lee Y-H, Cheng WT-K, et al. Amniotic fluid stem cells prevent follicle atresia and rescue fertility of mice with premature ovarian failure induced by chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106538–e. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106538.

Jensen F, Willis MA, Albamonte MS, Espinosa MB, Vitullo AD. Naturally suppressed apoptosis prevents follicular atresia and oocyte reserve decline in the adult ovary of Lagostomus maximus (Rodentia, Caviomorpha). Reproduction. 2006;132(2):301-8. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.1.01054.

Bhartiya D, Sharma D. Ovary does harbor stem cells - size of the cells matter! J Ovarian Res. 2020;13:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-020-00647-2.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C, literature search, data analysis and original draft preparation; C.R, data analysis and manuscript revision; A.S, literature search; G.S, study design and manuscript revision; R.H, article conception, supervision and critical revision. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chronopoulou, E., Raperport, C., Sfakianakis, A. et al. Elective oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility decline. J Assist Reprod Genet 38, 1177–1186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-021-02072-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-021-02072-w