Abstract

This paper explores the effects of unilateral tax provisions aimed at restricting multinationals’ tax planning on foreign direct investment (FDI). Using a unique dataset which allows us to observe the worldwide activities of a large panel of multinational firms, we test how limitations of interest tax deductibility, so-called thin-capitalization rules, and regulations of transfer pricing by the host country affect investment and employment of foreign subsidiaries. The results indicate that introducing a typical thin-capitalization rule or making it more tight exerts significant adverse effects on FDI and employment in high-tax countries. Moreover, in countries that impose thin-capitalization rules, the tax-rate sensitivity of FDI is increased. Regulations of transfer pricing, however, are not found to exert significant effects on FDI or employment.

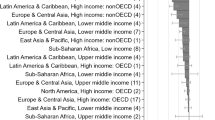

Source See the Appendix

Source Own computations based on Lohse and Riedel (2013)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We do not consider withholding taxes as they are usually fixed in bilateral tax treaties. It should also be noted that tax law provisions in the home country of the multinational may have important implications for the host countries’ tax effects on FDI as well. The current paper, however, focuses on measures by the host country.

While we focus on formal thin-capitalization rules, it should be noted that a country may also restrict excessive interest deduction by means of a general substance over form rule, although it has no explicit thin-capitalization rule.

See also the International Fiscal Association’s report on thin-capitalization, which provides an overview of thin-capitalization rules in 29 countries (Piltz 1996). More recent overviews about thin-capitalization rules in Europe are provided by Ambrosanio and Caroppo (2005) and Dourado and de la Feria (2008).

While thin-capitalization rules tend to identify profit-shifting using the level of debt, firms might resort to setting high interest rates at low debt levels. However, this would tend to conflict with the arm’s length principle and only offers limited leeway for profit shifting (Piltz 1996: 103 p).

Although countries often establish special rules for financial institutions and holdings, we do not report these ratios here as the corresponding subsidiaries are excluded from our empirical analysis. For instance, financial institutions in Australia enjoy a more generous debt-to-equity rule similar to banks and insurance companies in South Korea, or holding companies in Germany up to 2003. Similar exceptions hold in the Czech Republic and in Mexico.

The tightness indicator can be interpreted as the minimum share of capital that needs to be financed with equity capital in order to avoid tax penalties. To see this, note from above that interest deduction is not restricted if debt obeys \( D \; \le \; \sigma E. \) Denote the share of equity capital with \(\varepsilon .\) Then \( 1-\varepsilon \; \le \; \sigma \varepsilon \) and \(\varepsilon \; \ge \; \frac{1}{1+\sigma }.\)

Examples are the ‘cost plus method,’ the ‘transactional profit-split method,’ or the ‘transactional net-margin method.’

Also Haufler and Runkel (2012) provide a theoretical analysis of tax planning with restrictions of the interest deductibility.

An empirical analysis of the characteristics of firms with debt exceeding the safe haven debt-to-equity ratio is provided by Buettner et al. (2016).

Schindler and Schjelderup (2013) argue that regulation of transfer prices also affects the cost of profit-shifting via debt financing. This adds support to the joint analysis of the effects of transfer-pricing and thin-capitalization rules on FDI.

See Deutsche Bundesbank (2012), Statistische Sonderveroeffentlichung 10, Table 1.2a, Frankfurt.

Becker et al. (2012) emphasize that taxes also exert quality effects on FDI in the sense that taxation affects the profitability and labor intensity of FDI projects. Since our data mainly provide information on the volume of FDI and the number of employees, the exploration of the effects of profit-shifting rules on this dimension of FDI is left for future research.

The average tax rate of countries that have implemented thin-capitalization restrictions is about 35%, compared to a sample average of 33%. Also the variation in thin-capitalization rules is mainly observed in countries with higher tax rates. The two most important countries in our data with newly introduced TCRs are Italy and Poland with 5493 and 3922 observations and tax rates in the year before TCR implementation of 38.25% and 36%. Similarly, the most relevant case where a TCR has been made more strict is Canada (1784 observations) with a tax rate of 44.6% before the reform.

For surveys, see De Mooij and Ederveen (2003) or Feld and Heckemeyer (2011). In a meta-analysis, Feld and Heckemeyer (2011) find a higher tax effect but also note that studies using micro-level data (like our study) typically find significantly smaller tax effects in absolute values. For example, Wamser (2011) uses the same firm-level data and finds a tax semi-elasticity of about −0.5. Thus, the tax effect of about −0.83 found in column (1) of Table 2 is in accordance with previous findings.

Since Lohse and Riedel (2013) have shown that the transfer-pricing regulations have significant effects on profit shifting, it is an interesting question why the empirical results do not detect significant FDI effects of these regulations. A possible reason could be that the study by Lohse and Riedel (2013) is based on the Orbis dataset provided by Bureau van Dijk. This dataset includes multinational parent firms, whose headquarters can be anywhere around the world, and their foreign subsidiaries. In the MiDi data used in our study, only German parent firms are reporting their (worldwide) foreign transactions. If German firms find it easier to engage in profit shifting via internal debt or more difficult to engage in transfer pricing than MNCs from other countries, transfer pricing could be less of an option for their subsidiaries.

References

Alberternst, S., & Sureth-Sloane, C. (2015). The effect of taxes on corporate financing decisions evidence from the German Interest Barrier. WU International Taxation Research Paper Series (2015-09).

Ambrosanio, M. F., & Caroppo, M. S. (2005). Eliminating harmful tax practices in tax havens: Defensive measures by major EU countries and tax haven reforms. Canadian Tax Journal, 53, 685–719.

Bartelsman, E. J., & Beetsma, R. M. W. J. (2003). Why pay more? Corporate tax avoidance through transfer pricing in OECD countries. Journal of Public Economics, 87(9–10), 2225–2252.

Becker, J., & Fuest, C. (2012). Transfer pricing policy and the intensity of tax rate competition. Economics Letters, 117(1), 146–148.

Becker, J., Fuest, C., & Riedel, N. (2012). Corporate tax effects on the quality and quantity of FDI. European Economic Review, 56(8), 1495–1511.

Beuselinck, C., Deloof, M., & Vanstraelen, A. (2009). Multinational income shifting, tax enforcement and firm value. Working Paper, Tilburg University.

Blouin J., Huizinga H., Laeven L., & Nicodeme G. (2014). Thin Capitalization Rules and Multinational Firm Capital Structure. CentER Discussion Paper 2014-00, Tilburg.

Blouin, J. L., Robinson, L. A., & Seidman, J. (2010). Transfer pricing behaviour in a world of multiple taxes. Tuck School of Business Working Paper. 2010-74, Dartmouth.

Bucovetsky, S., & Haufler, A. (2008). Tax competition when firms choose their organizational form: Should tax loopholes for multinationals be closed? Journal of International Economics, 74, 188–201.

Buettner, T., Overesch, M., Schreiber, U., & Wamser, G. (2012). The impact of thin-capitalization rules on the capital structure of multinational firms. Journal of Public Economics, 96, 930–938.

Buettner, T., Overesch, M., & Wamser, G. (2016). Restricted interest deductibility and multinationals use of internal debt finance. International Tax and Public Finance, 23, 785–797.

Buettner, T., & Wamser, G. (2013). Internal debt and multinationals’ profit shifting—empirical evidence from firm-level panel data. National Tax Journal, 66, 63–95.

Buslei, H., & Simmler, M. (2012). The impact of introducing an interest barrier—evidence from the German corporation tax reform 2008. DIW Discussion Paper 1215, Berlin

Clausing, K. A. (2003). Tax-motivated transfer pricing and US intrafirm trade. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2207–2223.

De Mooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2003). Taxation and foreign direct investment: A synthesis of empirical research. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 673–693.

De Mooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2008). Corporate tax elasticities: A reader’s guide to empirical findings. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(4), 680–697.

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. R. (2004). A multinational perspective on capital structure choice and internal capital markets. Journal of Finance, 59, 2451–2487.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2012). Special Statistical Publication 10—Foreign direct investment stock statistics, Frankfurt.

Dischinger, M., & Riedel, N. (2011). Corporate taxes, profit shifting and the location of intangibles within multinational firms. Journal of Public Economics, 95, 691–707.

Dourado, A. P., & de la Feria, R. (2008). Thin capitalization rules in the context of the CCCTB. Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, Working Paper Series, WP 08/04.

Durst, M. C., & Culbertson, R. E. (2003). Clearing away the sand: Retrospective methods and prospective documentation in transfer pricing today. Tax Law Review, 57, 37–134.

European Commission. (1997). A package to tackle harmful tax competition in the European Union. COM(97) 564 final.

Feld, L., & Heckemeyer, J. H. (2011). FDI and taxation: A meta-study. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25, 233–272.

Gresik, T. A., Schindler, D., & Schjelderup, G. (2015). The effect of tax havens on host country welfare. CESifo Working Paper 5314, Munich.

Grubert, H. (2003). Intangible income intercompany transactions, income shifting, and the choice of location. National Tax Journal, 56, 221–242.

Harris, D. G. (1993). The impact of U.S. tax law revision on multinational corporations’ capital location and income shifting decisions. Journal of Accounting Research (Supplement), 31, 111–140.

Haufler, A., & Runkel, M. (2012). Firms’ financial choices and thin capitalization rules under corporate tax competition. European Economic Review, 56, 1087–1103.

Hong, Q., & Smart, M. (2010). In praise of tax havens: International tax planning and foreign direct investment. European Economic Review, 54, 82–95.

Huizinga, H., Laeven, L., & Nicodème, G. (2008). Capital structure and international debt shifting. Journal of Financial Economics, 88, 80–118.

Janeba, E. (1995). Corporate income tax competition, double taxation treaties, and foreign direct investment. Journal of Public Economics, 56, 311–325.

Janeba, E., & Smart, M. (2003). Is targeted tax competition less harmful than its remedies? International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 259–280.

Jost, S. P., Pfaffermayer, M., & Winner, H. (2014). Transfer pricing as a tax compliance risk. Accounting and Business Research, 44, 260–279.

Keen, M. (2001). Preferential regimes can make tax competition less harmful. National Tax Journal, 54, 757–762.

Lohse, T., & Riedel, N. (2013). Do Transfer Pricing Laws Limit International Income Shifting? Evidence from European Multinationals. CESifo Working Paper 4404, Munich.

Loretz, S. (2008). Corporate taxation in the OECD in a wider context. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(4), 639–660.

Lipponer, A. (2011). Microdatabase direct investment—MiDi. A brief guide. Technical Documentation, Frankfurt.

Mintz, J., & Smart, M. (2004). Income shifting, investment, and tax competition: Theory and evidence from provincial taxation in Canada. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1149–1168.

Mintz, J., & Weichenrieder, A. J. (2010). The indirect side of direct investment—Multinational company finance and taxation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

OECD. (1987). Thin-capitalization and taxation of entertainers, artistes and sportsmen, Committee on Fiscal Affairs. Issues in International Taxation No. 2, Paris.

OECD. (1998). Harmful tax competition: An emerging global issue. Paris.

OECD. (2011). Transfer pricing guidelines for multinational enterprises and tax administrations. Paris.

OECD. (2013). Action plan on base erosion and profit shifting. Paris.

OECD. (2015a). Transfer pricing documentation and country-by-country reporting. Action 13—2015 Final Report, Paris.

OECD. (2015b). Limiting base erosion involving interest deductions and other financial payments. Action 4—2015 Final Report, Paris.

Overesch, M., & Rincke, J. (2011). What drives corporate tax rates down? A reassessment of globalization, tax competition, and dynamic adjustment to shocks. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113, 579602.

Overesch, M., & Wamser, G. (2010). Corporate tax planning and thin-capitalization rules: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Applied Economics, 42, 563–573.

Peralta, S., Wauthy, X., & van Ypersele, T. (2006). Should countries control international profit shifting? Journal of International Economics, 68, 24–37.

Piltz, D. (1996). General report. Cahiers de Droit Fiscal, LXXXIb, 83–140.

Schindler, D., & Schjelderup, G. (2013). Transfer pricing and debt shifting in multinationals. CESifo Working Paper 4381, Munich.

Ruf, M., & Schindler, D. (2015). Debt shifting and thin-capitalization rules—German experience and alternative approaches. Nordic Tax Journal, 2015(1), 17–33.

Saunders-Scott, M. J. (2015). Substitution across methods of profit shifting. National Tax Journal, 68, 1099–1120.

Slemrod, J., & Wilson, J. D. (2009). Tax competition with parasitic tax havens. Journal of Public Economics, 93(11–12), 1261–1270.

Swenson, D. L. (2001). Tax reforms and evidence of transfer pricing. National Tax Journal, 54, 7–25.

Wamser, G. (2011). Foreign (in)direct investment and corporate taxation. Canadian Journal of Economics, 44, 1497–1524.

Wamser, G. (2014). The impact of thin-capitalization rules on external debt usage—A propensity score matching approach. Oxford Bulletin of Economics & Statistics, 76(5), 764–781.

Weichenrieder, A. J., & Windischbauer, H. (2008). Thin-capitalization rules and company responses—Experience from German legislation, CESifo Working Paper 2456, Munich.

Acknowledgements

We thank seminar participants at the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, at CESifo, Munich, and at the Free University of Berlin, for helpful comments. Data access by the Deutsche Bundesbank and financial support by the German Science Foundation (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Datasources

Appendix: Datasources

-

Micro-level data are taken from the micro-level dataset (MiDi) of the Deutsche Bundesbank (see Lipponer 2011, for an overview) using a version that covers the period from 1996 to 2007.

-

Corporate taxation data are taken from the International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation (IBFD) and from tax surveys provided by Ernst & Young, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), and KPMG. The statutory tax rate variable contains statutory profit tax rates modified by restrictions on interest deduction—as in the case of the Italian IRAP. For details on the tax rates used, see Table 5.

-

Thin-capitalization rules Basic information about thin-capitalization rules has been obtained from the same sources as the tax data. As in Buettner et al. (2012), this information was augmented and cross-checked with questionnaires sent out to country experts of PricewaterhouseCoopers. Table 6 provides the safe haven debt-to-equity ratios.

-

Transfer-pricing regulations are taken from the study by Lohse and Riedel (2013) who provide a classification of the strictness of national transfer-pricing regulations, see Table 7 for details. The empirical analysis basically focuses on a binary variable, which is unity if the transfer-pricing regulations are categorized in the two top classes (class 4 or 5).

-

Macroeconomic indicators such as GDP and GDP per Capita in US dollars, current prices, as well as GDP Growth and Inflation are taken from the IMF World Development Indicators.

-

Heritage indicators ‘Financial Freedom’ and ‘Freedom from Corruption’ are taken from the Heritage Database. Scores range from 0 to 100.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buettner, T., Overesch, M. & Wamser, G. Anti profit-shifting rules and foreign direct investment. Int Tax Public Finance 25, 553–580 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-017-9457-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-017-9457-0

Keywords

- FDI

- Corporate taxation

- Profit shifting

- Thin-capitalization rules

- Transfer-pricing regulations

- Affiliate-level data

- Foreign subsidiary

- Employment

- Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS)

- OECD