Abstract

We provide a first attempt to include an off-balance sheet, implicit insurance to SIFIs into a consistent assessment of fiscal sustainability, for 27 countries of the European Union. We first calculate tax gaps à la Blanchard (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No 79, 1990) and Blanchard et al. (Revue économique de l’OCDE, 1990). We then introduce two alternative measures of implicit off-balance sheet liabilities related to the risk of a systemic bank crisis. The first one relies on microeconomic data at the bank level. The second one is based on econometric estimations of the probability and the cost of a systemic banking crisis. The former approach provides an upper evaluation of the fiscal cost of systemic banking crises, whereas the latter one provides a lower one. Hence, we believe that the combined use of these two methodologies helps to gauge the range of fiscal risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

When r<γ, an ever-rising primary deficit is consistent with the debt ratio not rising infinitely. Following Blanchard, we exclude this dynamic inefficiency case and assume r>γ.

Also labeled actuarial sustainability or no Ponzi game condition.

This assumption is standard in the literature. It is relaxed in Sect. 2.3.

It should be noted that, by subtracting nominal growth from the nominal interest rate, we exclude the possibility that intertemporal sustainability is achieved through an inflation tax. In the following, both nominal variables will be replaced by real ones, consistent with the Fisher effect.

Both the 60 % ratio and the objective of a stabilization of the debt ratio are ad hoc. The calculation of an optimal debt ratio is difficult and surely beyond the scope of this paper.

Hence, we use the definition of the debt that applies when assessing the compliance of Member states with the different European rules. However, we do not retain the 60 % threshold as our criterion for debt sustainability. We rather rely on the intertemporal budget constraint, as explained in Sect. 2.1.

Since agency ratings are discrete, some countries rank equally, which lowers the correlations.

One major discrepancy between our tax gaps and the three agency ratings concerns Hungary where very optimistic official forecasts lead to low tax gaps according to our methodology and to EC and IMF calculations, whereas all three rating agencies rank this country very low; see Appendix B.

It should be reminded here that the aim of the paper is less to asses the fiscal sustainability of individual Member states than to evaluate the impact of accounting for banking risks in such assessment. The 4-year horizon appears the most meaningful for this task, since the assumptions made to include the fiscal risk related to SIFIs cannot be applied to the 50-year horizon.

Multiple equilibria appear because the debt is found sustainable whenever it is believed sustainable, hence the interest rate is low; it is unsustainable whenever it is believed so, hence the interest rate is high.

We exclude the case where α+β>1/b 0, since this case brings instability: r−γ reacts so much to the deficit that it is impossible to find a sustainable path, whatever the fiscal adjustment.

Indeed, this is what happened in Greece in 2012.

See, e.g., European Commission, Public Finances in EMU, 2007: “[…] in 11 countries—Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, and Sweden—the current fiscal position would be consistent with sustainable public finances if there was no impact of ageing on public finances” (p. 58).

Another route is to avoid bank liabilities spreading to the public sector by setting strict rules of bail-in (such as the possibility to convert bonds into equity), so that banks are no longer bailed out. We come back to this issue in the conclusion of the paper.

Note that the cost incurred in the case of a banking crisis is partly explicit, e.g. deposit insurance schemes.

The number of banks is inflated in Spain and Germany by the importance of regional banks (Cajas and Landesbanken, respectively).

We use the full static balance sheet assumption here. Like European Commission (2011), we assume that bank losses are first absorbed by core capital. However, the European Commission uses an in-house model of bank default probability, whereas we directly use the EBA estimation of RWAs. We have checked that RWA never exceeds the total of the bank’s assets.

In the case of Sweden in the 1990s, the final cost for the taxpayer was negligible. However, Sweden seems to be the exception rather than the rule; see Laeven and Valencia (2008).

In the end of the section, we present a different scenario for x.

This range matches the estimations obtained in Sect. 4.

Discounting future losses affects marginally the results at the 4-year horizon; see Blanchard (1990).

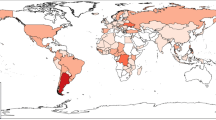

It can be argued that risk sharing brings no benefit if the risk is correlated across the Member states, hence if the crisis hits all Member states simultaneously. However, a mutualization of crisis costs may be necessary since the costs are unevenly distributed across Member states. As a matter of fact, such mutualization of bank recapitalization costs did take place in the Euro area during the 2009–2012 crisis. Then, the fact that banking crises are highly correlated in a financially-integrated zone such as the Euro area justifies analyzing a worst-case scenario of a general SIFI crisis, where p then represents the joint probability of a crisis hitting all countries simultaneously.

The Basel 3 reform strengthens the capital adequacy ratios of the banks, introduces a supplementary capital buffer over the cycle and for SIFIs, and adds liquidity requirements. See www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3/b3summarytable.pdf.

They do so by extrapolating the equity losses estimated for a 2 % decline in market returns.

We are grateful to Rob Capellini for making the data available to us. Unfortunately, not all 90 EBA’s systemic banks are covered by V-Lab.

Interestingly, though, the correlation between X and SRISK over the 55 bank sample is 89 %. Hence, the ranking of the risks is similar.

Additionally, due to incomplete coverage, we do not report any result for the Euro area.

We exclude the 2007–2009 banking crisis from the sample because the final (5-year ahead) cost cannot be assessed by the writing of this paper (see below).

The following variables were also tried: terms-of-trade variation, deposit interest rate (nominal and real), exchange-rate variation, inflation (GDP deflator), net lending/net borrowing to GDP, debt to GDP, private consumption to GDP, growth rate of real imports, current-account balance in percent of GDP, equity-price index, domestic claims to private sector in percent of GDP, growth of domestic credit, liquid reserves to total bank assets, total claims to broad money, foreign claims to broad money, growth of domestic claims to private sector in percent of GDP, private credit by deposit money banks in percent of GDP, private credit by deposit money banks and other financial institutions in percent of GDP, growth of foreign total liabilities in percent of GDP, growth of total reserves minus gold, banks capital to assets, growth of population, M3 to GDP, net foreign assets to GDP, over or undervaluation of local currency (PPP conversion factor to market exchange rate ratio), income-level dummies.

Country dummies or fixed effects are not appropriate here due to the limited number of crisis events over our sample.

A panel data, random or fixed-effect, logit estimation with simulated maximum likelihood and conditional logit model was also tried. The maximum likelihood estimations did not converge and the small number of countries experiencing a crisis reduced the sample to less than 700 rows. We also tried skewed logit regression and a log linear model specification, which are supposed to be more adapted to rare events, but the functional forms were rejected.

Here, we select the EBA approach rather than the V-Lab one due to its extended coverage.

References

Abbey, J. (2001). Fiscal irresponsibility and fiscal illusion. Centre for Policy Analysis.

Acharya, V., Dreschler, I., & Schnabl, P. (2011). A pyrrhic victory? Bank bailouts and sovereign credit risk. NBER Working Papers 17136, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Acharya, V. V., Pedersen, L. H., Philippon, T., & Richardson, M. (2010). Measuring systemic risk. Mimeo, New York University.

Alesina, A., & Ardagna, S. (2012). The design of fiscal adjustments. Mimeo.

Andrews, M., Piris Chavarri, A., Kawakami, Y., Frécaut, O., He, D., Hoelscher, D. S., Josefsson, M., Moretti, M., Quintyn, M., Taylor, M., & Delgado, F.-L. (2004). Managing systemic banking crises. IMF occasional papers 224, International Monetary Fund.

Blanchard, O. J. (1990). Suggestions for a new set of fiscal indicators. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No 79.

Blanchard, O. J., Chouraqui, J.-C., Hagemann, R., & Sartor, N. (1990). La soutenabilité de la politique budgétaire: nouvelles réponses à une question ancienne. Revue économique de l’OCDE.

Bohn, H. (1995). The sustainability of budget deficits in a stochastic economy. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 27(1), 257–271.

Caprio, G. J., D’Apice, V., Ferri, G., & Puopolo, G. W. (2010). Macro financial determinants of the great financial crisis: implications for financial regulation. MPRA Paper 26088, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Cebotari, A. (2008). Contingent liabilities: issues and practice. IMF Working Papers 08/245, International Monetary Fund.

Currie, E. (2002). The potential role of government debt management offices in monitoring and managing contingent liabilities. World Bank Report.

Currie, E., & Velandia, A. (2002). Risk management of contingent liabilities within a sovereign asset-liability framework.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Detragiache, E. (1997). The determinants of banking crises: evidence from industrial and developing countries. Policy Research Working Paper Series 1828, The World Bank.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Detragiache, E. (1999). Monitoring banking sector fragility: a multivariate logit approach with an application to the 1996–97 banking crises. Policy Research Working Paper Series 2085, The World Bank.

Detragiache, E., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2005). Cross-country empirical studies of systemic bank distress: a survey. IMF Working Papers 05/96, International Monetary Fund.

European Banking Authority (2011). EU-wide stress test aggregate report. Technical report, EBA.

European Commission (2009). Sustainability report. Technical report.

European Commission (2010). Public finances in EMU. Technical report.

European Commission (2011). Public finances in EMU. Technical report.

Hamilton, J., & Flavin, M. (1986). On the limitations of government borrowing: a framework for empirical testing. The American Economic Review, 76(4), 808–819.

Hardy, D. C., & Pazarbasioglu, C. (1999). Determinants and leading indicators of banking crises: further evidence. IMF Staff Papers, 46(3), 1.

Hemming, R. (2006). Public private partnerships, government guarantees and fiscal risk. IMF staff paper.

Honohan, P. & Laeven, L. (Eds.) (2005). Systemic financial crises. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Monetary Fund (2011). Fiscal monitor. Technical report.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2008). Systemic banking crises: a new database. IMF Working Papers 08/224, International Monetary Fund.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2010). Resolution of banking crises: the good, the bad, and the ugly. IMF Working Papers 10/146, International Monetary Fund.

Merton, R. C. (1977). An analytic derivation of the cost of deposit insurance and loan guarantees an application of modern option pricing theory. Journal of Banking & Finance, 1(1), 3–11.

Polackova, H. (1998). Contingent liabilities: a threat to fiscal policy. World Bank PREMnotes—Economic policy.

Polackova, H. (1999). Contingent government liabilities: a hidden fiscal risk. Finance and Development, 36(1).

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2010). From financial crash to debt crisis. NBER Working Papers 15795, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

VLAB (2011). Measuring and managing global systemic risk. Presentation, NYU Stern School of Business.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Data sources for tax gaps

We use Maastricht definitions of fiscal deficits and debts. Accordingly, general government debt is defined as the total of gross debts at face value, at the end of the current year. Maastricht accounting consolidates the debts of the various government sub-sectors. Note that currency and deposits are included as liabilities of the central banks, but equity and derivatives are excluded from the Maastricht definition of government debt. However, the streams of interest payments related to derivatives are included in the measure of the deficit. The government debt variation then is the sum of net borrowing by the general government and of the net purchase of financial assets. It is adjusted for the variation of non-Maastricht liabilities, capital gains or losses, and miscellaneous items.

-

For both horizons, we recover the end-2010 government (gross) debt ratio and 2011 government receipt ratio from EC’s Economic Forecasts of the Autumn 2011.

-

For the 4-year horizon, we use Convergence and Stability reports available in 2011. The reports provide fiscal and economic projections prepared by each Member state within the Stability and growth pact (SGP) procedure. From these reports, we recover projected deficits, growth, and inflation rates for years 2011 to 2014. We recover the implicit interest rate on the debt by dividing projected interest expenditures of year t by the debt level at the end of t−1. Note that Convergence and Stability reports have an optimistic bias since they are designed to comply with the budget balance requirement of the SGP in the medium term.

-

For the 50-year horizon, we rely on the same data as above up to 2014, and on interpolations from Public Finances in EMU 2009 and the Ageing Report 2009 (baseline scenario) for 2015–2060. These two reports provide public spending ratios (including ageing-related expenditures) on a decade-by-decade basis, and the Ageing Report also provides average growth rates from 2010 to 2060. We follow the European Commission (Sustainability Report 2009) in assuming a real interest rate of 3 % from 2015 to 2060.

Appendix B: Ranking comparisons

Appendix C: Econometric analysis—definitions and sample

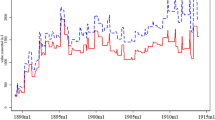

We concentrate on systemic banking crises defined by Laeven and Valencia as “Significant signs of financial distress in the banking system […], and significant banking policy intervention measures in response to significant losses in the banking system” (Laeven and Valencia 2010, p. 6). These authors further quantify these events in the following way: “we consider a sufficient condition for a crisis episode to be deemed systemic when either a country’s banking system exhibits significant losses resulting in a share of non-performing loans above 20 % or bank closures of at least 20 % of the banking assets, or fiscal restructuring costs of the banking sector are sufficiently high exceeding 5 % of GDP” (Laeven and Valencia 2010, pp. 6–7). They identify 124 episodes of such crises. The end of a crisis is defined as “the year before two conditions hold: real GDP growth and real credit growth are positive for at least two consecutive years.” They also truncate crisis duration at 5 years to “keep the rule simple” (Laeven and Valencia 2010, p. 10).

The fiscal cost of systemic banking crises is taken from Laeven and Valencia (see the methodology in Andrews et al. 2004 and Honohan and Laeven 2005). We use the gross fiscal cost in percent of GDP, which is defined as: “the outlays of the government and central bank in terms of bond issuance and disbursement from the treasury for liquidity support, payout of guarantees on deposits, costs of recapitalization and purchase of nonperforming loans” (p. 4 of Andrews et al. 2004) from the outbreak of the crisis to 5 years later. Our measure of gross cost includes interest payments on the debts incurred by the government to tackle the crisis. However, we consider of second order the additional interest payments related to the additional level of debt, which allows us to include the cost of banking crises directly as primary expenditures in our tax-gap calculations. Conversely, the gross fiscal cost excludes the cost of guarantees that have not been paid.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Roussellet, G. Fiscal sustainability in the presence of systemic banks: the case of EU countries. Int Tax Public Finance 21, 436–467 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9273-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9273-0