Abstract

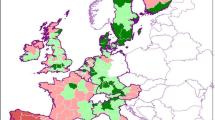

This paper investigates the patterns and determinants of the co-movement of economic activity between regions in the European Union and the Euro Area. We use a panel dataset of 208 regions over the period 1989–2002 and estimate a system of simultaneous equations to analyse the impact of regional trade integration, industry specialisation and exchange rate volatility on regional output growth synchronisation with the Euro Area. We find that deeper trade integration with the Euro Area had a strong direct positive effect on the synchronisation of regional output growth with the Euro Area. Industrial specialisation and exchange rate volatility were sources of cyclical divergence. Industrial specialisation had however an indirect positive effect on regional output growth synchronisation via its positive effect on trade integration, while exchange rate volatility had an indirect additional negative effect on regional output growth synchronisation by reducing trade integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Haan et al. (2008) for a review of recent research on the synchronisation of business cycles in the European Economic and Monetary Union and its underlying factors.

The analysed regions are classified as NUTS 2 regions according to the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) of the EUROSTAT—the statistical office of the European Union.

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom.

Quarterly data is not available at regional level. Furthermore, as pointed out by Giannone et al. (2009) annual data is less affected by measurement error in comparison to quarterly data.

Classified according to NACE at 2 digit level: mining and energy; food, beverages, tobacco; textiles and clothing; fuels, chemicals, rubber and plastic products; electronics; transport equipment; other manufacturing.

The members of the European Union as of 1992: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom.

Trade may also have an effect on the exchange rate volatility since economies which trade intensively with each other have similar consumption baskets and a price increase in a particular product will be passed to the trading partner so that the real exchange rate remains unchanged (Broda and Romalis 2009). Since our trade data refers to the regional level and the exchange rate volatility to the national level we cannot estimate this potentially indirect relationship.

Using averages of output growth over 5 years has the advantage to avoid an incorrect classification of leading or lagging behaviour of outliers as a missed co-movement of economic activity. We thank one anonymous referee for suggesting this point to us.

See Giannone et al. (2009) for a discussion of this argument. They also point out that annual data is less affected by measurement error in comparison to quarterly statistics.

NUTS 2 regions in Austria, Belgium, France, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain.

NUTS 2 regions in Denmark, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Imbs (2004) estimates a model of four simultaneous equations to identify the direct and indirect effects of trade intensity, industrial specialisation and financial integration on business cycle correlations using a cross section of 22 OECD countries. In contrast to Imbs, we use a panel data model allowing for time invariant unobserved region fixed effects and time-specific common shocks.

Imbs and Wacziarg (2003) discuss this literature strand.

The average regional output growth synchronisation with the Euro Area has increased in all countries with the exception of Greece, Spain, Ireland, Austria and Sweden. Output growth correlations with the Euro Area have decreased in 71 regions, one third of the regions included in our analysis.

The hypothesis of joint equality of time invariant unobserved region characteristics effects in the pre-EMU and EMU periods is rejected by the corresponding F test: F(208, 6022) = 2.69, Prob > F = 0.000.

F(12, 8294) = 56.95, Prob > F = 0.0000.

References

Alesina A, Barro R (2002) Currency unions. Q J Econ 117(2):409–436

Artis M, Zhang W (1997) The international business cycle and the ERM: is there a “European” cycle? Int J Finance Econ 2:1–6

Artis M, Galvao AB, Marcellino M (2003) The transmission mechanism in a changing world. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4014, CEPR, London

Artis M, Marcellino M, Proietti T (2004) Characterising the business cycles for accession countries. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 4457, CEPR, London

Barrios S, de Lucio J (2003) Economic integration and regional business cycles: evidence from the Iberian regions. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 65:497–515

Barrios S, Brülhart M, Elliott R, Sensier M (2003) A tale of two cycles: co-fluctuations between UK regions and the Euro Zone. Manchester Sch 71(3):265–292

Baxter M, Kouparitsas M (2003) Trade structure, industrial structure, and international business cycles. Am Econ Rev 93(2):51–56

Baxter M, Kouparitsas M (2005) Determinants of business cycle co-movement: a robust analysis. J Monetary Econ 52:113–157

Bayoumi T, Eichengreen B (1997) Ever closer to heaven? An optimal currency area index for European Countries. Eur Econ Rev 41:761–770

Belke A, Heine JA (2006) Specialisation patterns and the synchronicity of regional employment cycles in Europe. Int Econ Econ Policy 3(2):91–104

Bergman M (2005) How synchronized are European business cycles? In: Jonung L (ed) Proceedings of the 2004 first annual DG ECFIN research conference on “business cycles and growth in Europe. European Economy No. 227, European Commission, Brussels

Bordo M, Helbling T (2003) Have national business cycles become more synchronized? NBER Working Papers No. 10130

Broda C, Romalis J (2009) Identifying the relationship between trade and exchange rate volatility. In: Takatoshi I, Rose AK (eds) Commodity prices and markets, East Asia seminar on economics 20. NBER, Cambridge

Buiter W (2000) Optimal currency areas: why does the exchange rate regime matter? Scot J Polit Econ 47:213–250

Calderón C, Chong A, Stein E (2007) Trade intensity and business cycle synchronization: are developing countries any different? J Int Econ 71(1):2–21

Canova F, Marrinan J (1998) Sources and propagation of international output cycles: common shocks or transmission? J Int Econ 46(1):133–166

Clark TE, van Wincoop E (2001) Borders and business cycles. J Int Econ 55(1):59–85

Cushman DO (1983) The effects of real exchange rate risk on international trade. J Int Econ 15(1–2):45–63

De Grauwe P, Mongelli F (2005) Endogeneities of optimum currency areas. What brings countries sharing a single currency closer together? ECB Working Paper No. 468, ECB, Frankfurt

De Nardis S, Goglio A, Malgarini M (1996) Regional specialization and shocks in Europe: some evidence from regional data. Rev World Econ 132(2):197–214

Fatás A (1997) EMU: countries or regions? Lessons from the EMS experience. Eur Econ Rev 41:743–751

Fidrmuc J (2004) The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria, intra-industry trade, and EMU enlargement. Contemp Econ Policy 22:1–12

Forni M, Reichlin L (2001) Federal policies and local economies: Europe and the US. Eur Econ Rev 45(1):109–134

Frankel F, Rose A (1998) The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. Econ J 108:1009–1025

Giannone D, Lenza M, Reichlin L (2009) Business cycles in the Euro Area. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 7124

Greene WM (2000) Econometric analysis. Prentice Hall International, Inc, New Jersey

Haan J, Inklaar R, Jong-A-Pin R (2008) Will business cycles in the Euro Area converge? A critical survey of empirical research. J Econ Surv 22(2):234–273

Imbs J (2004) Trade, finance, specialisation and synchronisation. Rev Econ Stat 86(3):23–734

Imbs J, Wacziarg R (2003) Stages of diversification. Am Econ Rev 93(1):63–86

Inklaar R, Jong-A-Pin R, Haan J (2008) Trade and business cycle synchronization in OECD countries—A re-examination. Eur Econ Rev 52:646–666

Kenen P (1969) The theory of optimum currency areas: an eclectic view. In: Mundell R, Swoboda AK (eds) Monetary problems of the international economy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 41–60

Kose A, Otrock C, Whiteman C (2003) International business cycles: world, region, and country-specific factors. Am Econ Rev 93(4):1216–1239

Krugman P (1993) Lessons of Massachusetts for EMU. In: Giavazzi T, Torres F (eds) Adjustment and growth in the economic and monetary union in Europe. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 241–261

McKinnon R (1963) Optimum currency areas. Am Econ Rev 52:717–725

Micco A, Stein E, Ordonez G (2003) The currency union effect on trade: early evidence from EMU. In: Baldwin R, Bertola G, Seabright P (eds) EMU: assessing the impact of the Euro. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp 23–51

Mundell R (1961) A theory of optimum currency area. Am Econ Rev 51:657–665

Mundell R (1973a) A plan for a European currency. In: Johnson H, Swoboda A (eds) The economics of common currencies. Allen and Unwin, London, pp 143–173

Mundell R (1973b) Uncommon arguments for common currencies. In: Johnson H, Swoboda A (eds) The economics of common currencies. Allen and Unwin, London, pp 114–132

Schiavo S (2008) Financial integration, GDP correlation and the endogeneity of optimum currency areas. Economica 75:168–189

Stockman A (1988) Sectoral and national aggregate disturbances to industrial output in seven European countries. J Monetary Econ 21(2–3):387–409

Traistaru I (2004) Transmission channels of business cycles synchronisation in an enlarged EMU. ZEI Working Paper No B04-18, Center for European Integration Studies, University Bonn

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Acknowledgments

We thank Ray Barrell, Fritz Breuss, David Bell, Xiaoheng Zhang, Konstantinos Angeloupoulos, two anonymous referees and participants at the Congress of the European Regional Science Association in Amsterdam, the Irish Economics Association Conference in Bunclody, the EUROFRAME Conference in Berlin, and the European Trade Study Group Conference in Vienna for helpful comments and suggestions. Iulia Siedschlag gratefully acknowledges financial support from the 5th RTD Framework Programme of the European Communities (Contract No. HPSE-CT-2002-00118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Variable definitions and data sources

Appendix: Variable definitions and data sources

1.1 CORRY: regional output growth synchronisation with the Euro Area

Pearson correlations of annual growth rates of real regional gross value added and Euro Area real gross value added computed over 5-year rolling windows. Data on real gross value added is taken from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics. To account for the fact that while this variable takes values between −1 and 1, the independent variables are not bound, we use in regressions the following transformed variable: \( {\text{CORRY}}_{it}^{*} = \frac{1}{2}\ln \left( {{\frac{{1\,+\,{\text{CORRY}}_{it} }}{{1 \,-\, {\text{CORRY}}_{it} }}}} \right) \) as suggested by Inklaar et al. (2008).

1.2 SPEC: industrial specialisation index

The industrial specialisation index is computed using regional gross value added disaggregated on the following seven NACE 2 digit industry sectors: mining and energy; food, beverages and tobacco; textiles and clothing; fuels, chemicals, rubber and plastic products; electronics; transport equipment; other manufacturing. The specialisation index for region i is defined as follows: \( {\text{SPEC}}_{i} = \sum\nolimits_{j = 0}^{N} \vert {s_{ij} - s_{{{\text{Euro}},j}} }\vert. \) s ij is the share of sector j in region i and s Euro,j is the share of sector j in the Euro Area. This index takes values from 0 to 2. A value equal to 0 indicates complete similarity of industrial structure, and a value equal to 2 indicates total specialisation. The variable is included in regressions in logs. Data is taken from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics.

1.3 TRADE: regional exports to the Euro Area as share of gross value added

Total exports of each region to the Euro Area are estimated using NACE two-digit national exports provided by the WIFO-World Trade Databank (based on UN Trade Statistics) and NACE two-digit regional gross value added from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics. National exports of a product sector j are allocated to regions using the share of each region in the gross value added of sector j in total national gross value added. Total regional exports is then the sum of exports in all sectors j,…,N.

1.4 EVAR: exchange rate volatility

Exchange rate volatility is proxied by the standard deviation of the first difference of the log of the exchange rate index over five years corresponding to the rolling windows of the growth cycles. We use monthly nominal market exchange rates of national currencies per unit of Ecu/Euro from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics.

1.5 GDP SUM: log of product of per capita real regional value added and per capita Euro Area real gross value added

Regional real gross value added per capita from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics.

1.6 GDP GAP: log of the ratio of a region’s per capita real gross value added and Euro Area per capita real gross value added

Regional real gross value added per capita is taken from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics. Cambridge Econometrics. GAP > 0 for regions with per capita gross value added greater than the Euro Area aggregate; GAP < 0 for regions with per capita gross value added lower than the Euro Area aggregate.

1.7 POP: log of regional population in persons

Population in thousand persons from the European Regional Database, Cambridge Econometrics.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siedschlag, I., Tondl, G. Regional output growth synchronisation with the Euro Area. Empirica 38, 203–221 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-010-9130-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-010-9130-7