Abstract

This contribution analyses a market with an upstream bottleneck monopoly and a downstream activity that may either be vertically integrated or separated. Separation always reduces the consumer surplus, and the total surplus unless there are large cost reductions. Downstream competition from a public or private network monopoly would crowd out other firms, also when public ownership is associated with more modest objectives than welfare-maximisation. A market is therefore less likely to remain a mixed oligopoly than without vertical relations. However, private firms would survive in a moderately welfare-improving mixed oligopoly with cross-subsidisation and access charges equal to marginal costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, it was believed that the retail trade of electricity is no longer a natural monopoly because of increasing demand and that the introduction if competition would stimulate entry and hence lead to lower prices (Sioshansi and Hamlin 2004).

A companion paper (Grönblom and Willner 2008) focuses on endogenous cost differences caused by different wage-bargaining conditions. Vertical separation can then create an effect that reminds of double marginalisation even if the upstream firm is regulated and makes zero profits.

Marginal costs here refer to the derivative of the cost function with respect to output, and not for example the number of connections.

Free entry would mean approximately m −1/2−1 firms, whereas the largest total surplus would be achieved if n is the nearest integer to m −1/3−1, which is lower (Mankiw and Whinston 1986).

In a wider sense a natural monopoly means that even a commercial monopoly would be more beneficial than competition even if entry is possible (Vogelsang 1988), although it is more usual to use a definition based on how many firms that can survive.

We might alternatively assume free entry given p until the profits are zero, in which case we would get approximately \([(a-pz)/\sqrt{F}]-1\) firms, which would yield \(y^{D}=a-pz-\sqrt{F}\) and hence a different upstream demand function. Similar calculations as above then yield the total surplus \([3(a-cz-\sqrt{F})^{2}/8]-F_0. \)

To prevent downstream competition requires strictly speaking regulation, so some authors use the term liberalisation only when there is completely free entry downstream, also for the incumbent monopoly (Buehler 2005).

Higher cost efficiency is in addition only necessary but not sufficient for higher welfare in imperfectly competitive industries (see Willner 1996).

Some studies also allow for different interpretations. Hayashi et al. (1987) found public ownership more efficient in the 1960s and less efficient in the 1970s in the US. As for Spain, public ownership tends to be more efficient under cost-of-service regulation, but less efficient under price-cap regulation (Arocena and Waddams Price 2002). Pollitt (1995) compares plants in 14 countries and finds public plants and transmission equally efficient in a technical and managerial sense, but often associated with restrictions that require a less efficient input mix.

Competition is also often believed to be more efficient than regulation, which maybe associated with similar disadvantages as public ownership. For example, if capture by different interest-groups leads to higher costs in a public monopoly, the same would probably apply to regulation as well (Newbery 2001).

References

Arocena P, Price CW (2002) Generating efficiency: economic and environmental regulation of public and private electricity generators in Spain. Int J Ind Organ 20(1):41–69

Atkinson S, Halvorsen R (1986) The relative efficiency of public and private firms in a regulated environment: the case of US electric utilities. J Public Econ 29:281–294

Bagdadioglu N, Price CMW, Weyman-Jones TG (1996) Efficiency and ownership in electricity distribution: a non-parametric model of the Turkish experience. Energy Econ 18(1):1–23

Borcherding TE, Pommerehne WW, Schneider F (1982) Comparing the efficiency of private and public production: the evidence from five countries. Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie Suppl 2:127–156

Boyd CW (1986) The comparative efficiency of state owned enterprises. In: Negandhi AR (ed) Multinational corporations and state-owned enterprises: a new challenge in international business. Research in International Business and International Relations, JAI Press, Greenwich, Conn and London

Buehler S (2000) Is Swiss telecommunications a natural monopoly? An evaluation of empirical evidence. Working Paper, University of Zürich

Buehler S (2005) The promise and pitfalls of restructuring network industries. German Econ Rev 6(2):205–228

De Alessi T (1974) An economic analysis of government ownership and regulation: theory and evidence from electric power industry. Public Choice 19(1):1–42

De Graba P (2003) A bottleneck input supplier’s opportunity cost if competing downstream. J Regulat Econ 23(3):387–297

De Fraja G, Flavio D (1990) Game theoretic models of mixed oligopoly. J Econ Surv 4(1):1–18

Färe R, Grosskopf S, Logan J (1985) The relative performance of publicly owned and privately owned electric utilities. J Public Econ 26(1):89–106

Florio M (2004) The great divestiture. Evaluating the impact of the British privatizations 1979–1997. MITPress, Cambridge

Foreman-Peck JO, Waterson M (1985) The comparative efficiency of public and private enterprise in Britain: electricity generation between the world wars. Econ J 95:83–95

Fraquelli G, Erbetta F (2000) Privatisation in Italy: an analysis of factor productivity and technical efficiency. In: Parker D (ed) Privatisation and corporate performance. Edward Elgar, Aldershot

Fraquelli G, Piacenza M, Vannoni D (2004) Cost savings from generations and distribution with an application to Italian electric utilities. Working Paper, Presented at EARIE 2004 in Berlin

Grönblom S, Willner J (2008) Privatization and liberalization: costs and benefits in the presence of wage-bargaining. Ann Public Coop Econ 79(1):133–160

Hausman WJ, Neufeld JL (1991) Property rights versus public spirit: ownership and efficiency of US electric utilities prior to rate or return regulation. Rev Econ Statist 73(3):414–423

Hayashi PM, Sevier M, Trapani JM (1987) An analysis of pricing and production efficiency of electric utilities by mode of ownership. In: Crew MA (ed) Regulating utilities in an era of deregulation. Macmillan Press, Houndmills and London

Hjalmarsson L, Veiderpass A (1992) Efficiency and ownership in Swedish electricity retail distribution. J Productiv Anal 3(1):7–23

Kay JA, Thompson DJ (1986) Privatisation: a policy in search of a rationale. Econ J 96:18–32

Kumbakhar SC, Hjalmarsson L (1998) Relative performance of public and private ownership under yardstick competition: electricity retail distribution. Eur Econ Rev 42:97–102

Künneke RW (1999) Electricity networks: how ‘natural is the monopoly?’ Util Policy 8:99–108

Mankiw NG, Michael DW (1986) Free entry and social inefficiency. Rand J Econ 17(1):48–58

Martin S (1993) Endogenous firm efficiency in a cournot principal-agent model. J Econ Theory 59(2):445–450

Martin S, Parker D (1997) The impact of privatization. Ownership and corporate performance in the UK. Routledge, London and New York

Megginson WL, Netter JM (2001) From state to market: a survey of empirical studies on privatization. J Econ Lit 39(2):321–389

Meyer RA (1975) Publicly owned versus privately owned utilities: a policy choice. Rev Econ Statist 57(4):391–399

Millward R (1982) The comparative performance of public and private ownership. In: Roll LE (ed) The mixed economy. Macmillan, London

Millward R, Parker D (1983) Public and private enterprise: comparative behaviour and relative efficiency. In: Millward R, Parker D, Rosenthal L, Sumner MT, Topham N (eds) Public sector economics. Longman, London

Moore TG (1970) The effectiveness of regulation of electric utility prices. South Econ J 37:365–375

Nelson RA, Primeaux WJ Jr (1988) The effects of competition on transmission and distribution costs in the municipal electric industry. Land Econ 64(4):338–346

Neuberg LG (1977) Two issues in the municipal ownership of electric power distribution systems. Bell J Econ 8:303–323

Newbery DM (2001) Privatization, restructuring and regulation of network utilities. MIT Press, Cambridge

Newbwry DM (2003) Privatising network industries. CESifo Conference Paper, Cadenabbia, 1–3 November

Perry MK (1978) Vertical integration: the monopoly case. Am Econ Rev 68:561–570

Pescatrice DR, Trapani JM (1980) The performance of public and private utilities operating in the United States. J Public Econ 13(3):259–276

Peters LL (1993) For-profit and non-profit firms: limits of the simple theory of attenuated property rights. Rev Ind Organ 8(5):623–634

Pollitt MG (1995) Ownership and performance in electric utilities: the international evidence on privatization and efficiency. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sioshansi F, Hamlin LD (2004) Competitive, regulated, or somewhere in between? Where do we go from here? Electric J 87–94

Spann RM (1977) Public versus private provision of public services. In: Borcherding TE (ed) Budgets and bureaucrats. Duke University Press, Durham NC

Thomas S (2004) Evaluating the British model of electricity deregulation. Ann Public Coop Econ 75(3):367–398

Thomas S (2004b) Electricity industry reforms in smaller EU countries; Experience from the Nordic region. Working Paper, Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), University of Greenwich

Vickers J (1995) Competition and regulation in vertically related markets. Rev Econ Stud 62(1):1–18

Vickers J, Yarrow G (1988) Privatization: an economic analysis. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Vogelsang I (1988) Regulation of public utilities and nationalised industries, Ch 3. In: Hare PG (ed) Surveys in public sector economics. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, pp 45–67

Whinston MD (1990) Tying, foreclosure, and exclusion. Am Econ Rev 80(4):837–859

Willner J (1996) A comment on Bradburd: privatisation of natural monopolies. Rev Ind Organ 11(6):869–882

Willner J (2001) Ownership, efficiency, and political interference. Eur J Polit Econ 17(6):723–748

Willner J (2003) Privatization: a sceptical analysis, Chap 4. In: Parker D, Saal D (eds) International handbook on privatization. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp 60–86

Willner J (2006) Privatisation and public ownership in Finland, Chap 5. In: Koethenbuergher M, Sinn H-W, Whalley J (eds) Privatisation experiences in the EU. MITPress and CESifo, Cambridge, UK pp 141–162

Yunker JA (1975) Economic performance of public and private enterprise. J Econ Bus 28(1):60–75

Acknowledgements

This contribution is part of the project Reforming Markets and Organisations, which is partly funded by the Academy of Finland (Research Grant 115003). I am grateful to the referee and editors of this journal, to a referee of a related paper, to Sonja Grönblom, Annica Karlsson, Tom Björkroth and other present or former members of my department’s research group in industrial organization, and to participants in European Network on Industrial Policy, 9th Annual Conference, Limerick, 19-22.2006. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1 (a)

The prices in a vertically integrated monopoly and an n-firm Cournot-oligopoly are r M = (a + zc)/2, and r C = [(n + 2)a + nzc]/2(n + 1) respectively (see Sect. 2); it is obvious that r C > r M. Separation and competition then unambiguously reduce the total surplus:

As for free entry, it is obvious that the sign of (A.1) does not change by substituting \([(a-cz)/2\sqrt{F}]-1\) for n.

(b) The result follows from straightforward manipulation of (5) and (11) and substituting n* for \([(a-cz)/2\sqrt{F}].\) □

Proof of Proposition 2 (a)

Suppose that sunk costs in the public firm are denoted F G and F G0 respectively, so that (6) becomes

As the consumer surplus is equal to y 2/2, it is sufficient to compare (A.2) to the output levels y M, y C, and y D respectively. It is obvious that a sufficient condition for part a) to hold true is that the square root in (A.2) greater than zero.

(b) Suppose that n firms would be able to break even after privatisation, vertical separation and free entry, so that the downstream sunk costs are \(F\approx(a-cz)^{2}/4(n+1)^{2}\) and that but n(a − cz)2/4(n + 1)2 in the integrated public monopoly. Use this to eliminate F from (6) and (10) and rearrange so that we get the following expressions for the total surplus:

Note that the public monopoly would still be able to break even, because the expression in the square root in (A.3) is positive if (A.4) is positive (or if a private monopolist can break even if n = 1). Suppose now that Proposition 2a is false and rearrange the antithesis as

which is equivalent to:

However, this cannot be true, for it can easily be verified that the second bracket from the left must be negative, so the antithesis is false. □

To see that the total surplus is higher in the vertically integrated public monopoly than in a profit-maximising monopoly or after separation and free entry, suppose that TS PM < TS M, as expressed by (5) and (9). This would mean

which cannot hold true. The fact that TS M > TS C and TS M > TS C (Proposition 1) mean that TS PM > TS C and TS PM > TS C. Part (a) is thereby proved.

Proof of Proposition 3

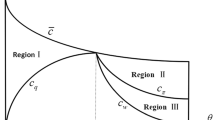

Inserting the solutions for y 0 and ŷ given p into (18) and differentiating with respect to p yields p = [(1 − ρ)a + cz]/(2 − ρ)z, for the Cournot-case, so the public firm would produce y 0 = (a − cz)/(2 − ρ), whereas the private firms would produce a zero output. Routine calculations yield the same solution for the Stackelberg case. □

Proof of Proposition 4 (a)

Note that the total surplus in a conventional oligopoly with n = m can be written

because of (25). As for the mixed oligopoly, rearrange the consumer surplus \((\hat{{y}}^{MO}+y_0^{MO})^{2}/2\) using (25):

Note that the profits are \((y_0\hat{{y}}/m)-F-F_0,\) because r − cz = y i . Using (25) yields:

Add (A.9) and (A.10) and compare to (A.8). It follows that the mixed oligopoly increases the total surplus as compared to a conventional downstream oligopoly if

which is true for all positive m. Part (a) is thereby proved. Part (b) is obvious because of (26) and the fact that profits are nonnegative; part (c) follows directly from (A.10). □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willner, J. Liberalisation, competition and ownership in the presence of vertical relations. Empirica 35, 449–464 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-008-9067-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-008-9067-2