Abstract

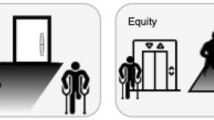

A number of theoretical and empirical studies have shown that the development of credit markets is affected by the efficacy of enforcement institutions. A less explored question in this context is how these institutions interact with turns in the economic cycle and the impact of different types of legal procedures on credit market performance. This paper fills these gaps by analyzing how differences in the availability of credit and the evolution of non-performing loans ratios may be partially explained by regional variations in the quality of loan contract enforcement during recent periods of sustained growth (2001–2007) and recession (since 2008) in the Spanish economy. This research concludes that a rise in the clearance rate of executions (i.e., when a judge enforces the repayment of a debt) increases the ratio of total credit to GDP. However, the declaratory stage of the procedure (i.e., when a debt is firstly verified by a judge) does not seem to be statistically significant. A possible explanation to this finding is that, throughout the economic cycle, a relevant proportion of the defaults that take place are strategic (i.e., defaults by a solvent debtor). Furthermore, it is observed that, in regions where declaratory procedures are more efficient, less credit is declared as non-performing. The latter effect, however, is only observed after the onset of the “Great Recession” in 2008. This may be related to the increase of non-strategic defaults during a downturn.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration

Source: Self elaboration using CGPJ data

Source: Self elaboration using CGPJ data

Source: Self elaboration using CGPJ data

Source: Self elaboration using CIR (Banco de España) data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is a growing strand of empirical literature that aims to disentangle supply and demand factors of credit growth. See, inter alia, Gan (2007), Khwaja and Mian (2008), Jimenez et al. (2012), García-Posada and Marchetti (2016), Bentolila et al. (2015). On the procyclicality of credit growth and lending standards see, inter alia, Berger and Udell (2003), Lown and Morgan (2006) and Rodano et al. (2015).

After a long period of expansion characterized by its high growth rates, the Spanish economy showed a negative quarterly GDP growth rate of −1.4% in the fourth quarter of 2008. A deep recession began in that moment and lasted until 2013.

Previous studies on the issue are usually based on estimations of judicial efficacy (thus, not real efficacy data): for instance the indicator proposed by Djankov et al. (2003) which inspired the Doing Business (DB) project (contract enforcement indicator) or the DB data directly. Measures which proxy the length of the procedure used in other studies (such as Fabbri 2010) are again estimations (in that case, at the region level).

For an analysis of the Spanish “Great Recession” see Jimeno and Santos (2014).

Data obtained from official sources: Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), Banco de España—Eurosystem and the Ministry of Housing.

This study shows that more effective courts, measured using real performance data at the local level, seem to promote higher entry rates of entrepreneurs in Spain.

More specifically, Spain is ranked 26 out of a total of 35 legal systems in terms of its agility to resolve disputes before the first instance courts. Spain obtains a better result than the “average” civil law country, but worse than the average Common Law or German Law countries.

The Spanish judicial system is divided into four different jurisdictions (civil, labour, administrative and criminal), served by specialized judges. We must emphasize that in Spain, civil and labour jurisdictions are separated.

A ‘bills of exchange and cheques’ procedure takes place if a bill of exchange, a cheque or a promissory note is presented (Article 819 of the Civil Procedural Law). A ‘payment procedure’ takes place if someone seeking payment of a monetary debt, presents in the court evidence of the debt in the form of a document, an invoice and other similar options. The debt may be of any amount and must be liquid, determined, due and payable (Article 812 of the Civil Procedural Law).

Article 576 of the Civil Procedural Law.

Interestingly, in their study of the impact of judicial efficacy on firm size and growth, García-Posada and Mora-Sanguinetti (2015) find that the procedures at the declaratory stage are the ones that have an impact on those variables. This is an illustration of how complex is the issue of judicial efficacy and economic performance and how much further research is required in the area.

We have also analyzed the effect of another procedure, the verbal judgment, on the availability of credit and we have obtained similar results.

In the ordinary procedure, before reaching the judgment (declaration), the parties, under the supervision of the judge, go through many formal steps. Following the demand by the creditor and the defense by the debtor, there is a preliminary hearing of the parties (Article 414 of the Civil Procedural Law, CPL). Subsequently, the trial itself includes the examination of evidence, the formulation of conclusions by the parties and other reports (Article 433 of the CPL). While the parties cannot choose the particular judge that will resolve their case, they are obliged to go through all the parts of the procedure in the court assigned (for example, the court of first instance number 92 of Madrid or court of first instance number 31 of Barcelona). Citizens and businesses cannot intervene in the structure of the procedures (which are regulated and fixed by the CPL).

The previous law dated from 1881. The new CPL is Law 1/2000 of Civil Procedure and entered into force on January 8th, 2001.

We have adequately merged data from the “first instance” courts and from the “first instance and instruction” courts at the local level taking into account their weight within the different provinces.

The information provided by the CGPJ database does not include the content of judgments, i.e., the % of cases in which the judge decides in favour of the creditor or the debtor. This limits the possibilities to explore other issues such as potential judicial activism, which could also affect the availability of credit.

Results using the congestion rate are available on demand. The literature also discusses other measures that we consider less comprehensive, such as the pending cases rate, the resolution rate or the pending- plus-new cases (PPNC) rate (see, among others, Mora-Sanguinetti, 2012). Furthermore, measuring the predictability or the accessibility of the system (Palumbo et al. 2013) are also methods of comparing judicial systems, but ultimately they depend on the duration of proceedings.

Madrid is the capital of the country and the most populated region. Alicante is a coastal region, showing lower judicial efficacy. Navarra is a northern region, with high GDP per capita and high judicial efficacy.

We are including any instrument through which banks can provide credit to firms: financial loans, commercial loans, documentary credit, leasing, factoring, repos, securities lending and loans or credits transferred to a third party.

Specifically, we include public limited companies, limited liability companies, unlimited liability companies and companies of a hybrid nature. We do not include sole proprietorships.

Notice that we do not include undrawn credit facilities such as undrawn lines of credit.

All credit institutions that operate in Spain must report their credit exposures to the CIR. These comprise domestic credit institutions (commercial banks, savings banks, credit cooperatives and financial credit establishments) as well as foreign branches and subsidiaries of foreign banks.

The effect of the crisis itself will be captured by time dummies in our regressions.

A parallel debate is whether we observe in the province “j” the conflicts that actually took place in “j” (or there may be some kind of “forum shopping”). The CPL (Articles 50 and 51) states that the competent court to resolve the conflict will be that of the domicile of the defendant, both in the case of natural and legal persons. Therefore, this limits the possible problem of “forum shopping” and makes the analysis at the province level in our experiment satisfactory. However, we must also note that the Law allows the parties to agree to choose another place to resolve the conflict (Article 55) and there is also a certain choice for the plaintiff while can also sue a businessman (defendant) in the place where he does business (in disputes arising from his business or professional activity). The latter should not be a big problem while interprovincial mobility in Spain is low (except in Madrid and Barcelona) but this rule may open the possibility of choosing the forum in some cases. Parallel to this, we cannot observe the cases where a creditor decided “not to sue” (in other words, we only observe the conflicts that actually take place).

We thank an anonymous referee for raising this point.

For a discussion of the Spanish bankruptcy code and its two first reforms see Celentani et al. (2012).

The European Stability Mechanism disbursed a total of €41.3 billion to the Spanish government for the recapitalisation of the country’s banking sector.

Following the Royal Decree Law 2/2012 of February 3 and the Royal Decree Law 18/2012 of May 11, all banks had to make higher provisions on non-performing loans to real estate companies as well as provisions on performing loans to these companies and on land and buildings owned by the banks as a consequence of collateral repossession and dation in payment.

BFA-Bankia, Catalunya Banc, NCG Banco-Banco Gallego and Banco de Valencia.

As already noted, this analysis is performed for the ordinary procedures, which are the most consistent procedures with the type of loans for which we have information (those with an amount higher than 6000 euros). If we perform the analysis for verbal judgments, we find that a higher judicial efficacy in resolving this type of cases also contributes to reducing the default rate, especially during the crisis. However, no significant impact is found when estimating its effect on credit availability.

Note that we estimate a fixed effects model with the within-group estimator, which exploits variation over time within each region.

In the “appendix”, we show the results of the regression controlling for the initial level of efficacy prior to the crisis. The results indicate that the efficacy of court enforcement moderates the effect of the crisis on the NPL ratio.

For instance, in Granada, one of the provinces with a higher execution clearance rate, performing loans increased significantly in this period (from 45 to 65%).

References

Aghion, P., Fally, T., & Scarpetta, S. (2007). Credit constraints as a barrier to the entry and post-entry growth of firms. Economic Policy, 22, 731–779.

Bae, K. H., & Goyal, V. K. (2009). Creditor rights, enforcement, and bank loans. Journal of Finance, 64(2), 823–860.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2008). Finance, firm size, and growth. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(7), 1379–1405.

Bentolila, S., Jansen, M., Jiménez, G., & Ruano, S. (2015). When credit dries up: Job losses in the great recession. CEMFI working paper no. 1310.

Berger, A. N., & Udell, J. F. (2003). The institutional memory hypothesis and the procyclicality of bank lending behaviour. BIS working papers no 125.

Carmignani, A., & Giacomelli, S. (2010). Too many lawyers? Litigation in Italian civil courts. Temi di discussion (working papers), 745, Banca d´Italia.

Castelar Pinheiro, A., & Cabral, C. (1999). Credit markets in Brazil: The role of judicial enforcement and other institutions. Red de Centros de Investigación de la Oficina del Economista Jefe, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo, Documento de Trabajo R-368.

Celentani, M., García-Posada, M., & Gómez, F. (2012). The Spanish business bankruptcy puzzle. New York: Mimeo.

CEPEJ - European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (2014). Report on European judicial systems—Edition 2014 (2012 data): Efficiency and quality of justice.

Chemin, M. (2009). The impact of the judiciary on entrepreneurship: Evaluation of Pakistan’s access to justice programme. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1–2), 114–125.

Chemin, M. (2012). Does court speed shape economic activity? Evidence from a court reform in India. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 28(3), 460–485.

Desai, M., Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2005). Institutions, capital constraints and entrepreneurial firm dynamics: Evidence from Europe. Harvard NOM working paper no. 03-59.

Djankov, S., Hart, O., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. (2008). Debt enforcement around the world. Journal of Political Economy, 116(6), 1105–1149.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., López de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Courts. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 453–517.

Evans, D. S., & Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 808–827.

Fabbri, D. (2010). Law enforcement and firm financing: Theory and evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association, 8(4), 776–816.

Fabbri, D., & Padula, M. (2004). Does poor legal enforcement make households credit-constrained? Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(10), 2369–2397.

Gan, J. (2007). The real effects of asset market bubbles: Loan- and firm-level evidence of a lending channel. Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1941–1973.

García-Posada, M., & Marchetti, M. A. (2016). The bank lending channel of unconventional monetary policy: The impact of the VLTROs on credit supply in Spain. Economic Modelling, 58, 427–441.

García-Posada, M., & Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2014). Entrepreneurship and enforcement institutions: Disaggregated evidence for Spain. European Journal of Law and Economics, 40(1), 49–74.

García-Posada, M., & Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2015). Does (average) size matter? Court enforcement, business demography and firm growth. Small Business Economics Journal, 44(3), 639–669.

Giacomelli, S., & Menon, C. (2012). Firm size and judicial efficiency in Italy: Evidence from the neighbour’s tribunal. SERC discussion papers 0108, Spatial Economics Research Centre, LSE.

Ginsburg, T., & Hoetker, G. (2006). The unreluctant litigant? An empirical analysis of Japan’s turn to litigation. Journal of Legal Studies, 35, 31–59.

Jappelli, T., Pagano, M., & Bianco, M. (2005). Courts and banks: effects of judicial enforcement on credit markets. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 37, 224–244.

Jimenez, G., Ongena, S., Peydro-Alcalde, J., & Saurina, J. (2012). Credit supply and monetary policy: Identifying the bank balance-sheet channel with loan applications. The American Economic Review, 102(5), 2301–2326.

Jimeno, J. F., & Santos, T. (2014). The crisis of the Spanish economy. SERIEs, Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 5(2–3), 125–141.

Khwaja, A., & Mian, A. (2008). Tracing the impact of bank liquidity shocks: Evidence from an emerging market. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1413–1442.

La Porta, R., López de Silanes, F., Schleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131–1150.

La Porta, R., López De Silanes, F., Schleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113–1155.

Laeven, L., & Majnoni, G. (2005). Does judicial efficiency lower the cost of credit? Journal of Banking & Finance, 29(7), 1791–1812.

Levine, R. (1998). The legal environment, banks, and long-run economic growth. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 30(3), 596–613.

Lown, C., & Morgan, D. P. (2006). The credit cycle and the business cycle: New findings using the loan officer opinion survey. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 38(6), 1575–1597.

Méssonier, J., & Monks, A. (2015). Did the EBA capital exercise cause a credit crunch in the euro area? International Journal of Central Banking.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2010). A characterization of the judicial system in Spain: Analysis with formalism indices. Economic Analysis of Law Review, 1(2), 210–240.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2012). Is judicial inefficacy increasing the weight of the house property market in Spain? Evidence at the local level. SERIEs, Journal of the Spanish Economic Association, 3(3), 339–365.

Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S., & Garoupa, N. (2015). Do lawyers induce litigation? Evidence from Spain, 2001–2010. International Review of Law and Economics, 44, 29–41.

OECD (2013). What makes civil justice effective? OECD Economics Department Policy Notes.

Palumbo, G., Giupponi, G., Nunziata, L., & Mora-Sanguinetti, J. S. (2013). The economics of civil justice: New cross-country data and empirics. OECD economics department working papers no. 1060.

Ponticelli, J., & Alencar, L. (2016). Court enforcement, bank loans and firm investment: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(3), 1365–1413.

Qian, J., & Strahan, P. (2007). How law and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. Journal of Finance, 62(6), 2803–2834.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1421–1460.

Rodano, G., Serrano-Velarde, N., & Tarantino, E. (2015). Lending standards over the credit cycle. New York: Mimeo.

Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2011). Venture capital, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 338–349.

Shvets, J. (2013). Judicial institutions and firms’ external finance: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 29(4), 735–764.

Visaria, S. (2009). Legal reform and loan repayment: The microeconomic impact of debt recovery tribunals in India. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 59–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The three authors are members of the Research Department of the Banco de España-Eurosystem. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

We are grateful to Ildefonso Villán Criado for his advice in the use of the judicial performance data. We also thank Giovanni Ramello (for his editorial supervision), Claire McHugh, Alice Guerra, Francisco Cabrillo, two anonymous referees and the participants at the VI Annual Conference of the Spanish Association of Law and Economics (AEDE) (Santander, 2015), the 2nd International Workshop on Economic Analysis of Litigation (Torino, 2015), the 32nd Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics (EALE) (Vienna, 2015) and the Research seminar at the Banco de España for their comments and suggestions.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mora-Sanguinetti, J.S., Martínez-Matute, M. & García-Posada, M. Credit, crisis and contract enforcement: evidence from the Spanish loan market. Eur J Law Econ 44, 361–383 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-017-9557-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-017-9557-4