Abstract

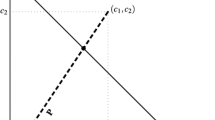

The Classical Athenians developed two formal arbitration procedures. They assigned low stakes disputes to a panel of arbitrators, while high stakes cases were handled by a single arbitrator. Given the information aggregation benefit of collective decision making, one would have expected more individuals to be assigned to more important cases. I develop a theoretical model to provide an explanation for their design. Recognizing that arbitrator competence is endogenous, effort put into making a good decision takes time and effort. In larger groups free riding is a concern. Consequently, there exists environments where the free-riding loss is magnified in higher stakes disputes to the point where the socially optimal panel size is inversely related to the stakes involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I date the Classical Period by the political structure. Thus, the period begins with Cleisthenes’, the “father of Athenian democracy”, creation of the constitution in 508 B.C. after the removal of the tyrant, to 322 B.C. with the death of Alexander the Great and the rise of the monarchies of the Successors. See McCannon (2011) for a social choice analysis of jury composition and structure in Classical Athens. Also, see MacDowell (1978) for his seminal volume cataloging Athenian legal procedures and Aristotle's Constitution of Athens for details. The introduction of public arbitrators likely occurred in the mid-sixth century A.D. during the Peisistratos’ rule prior to the Classical period.

The Athenians did have cost-saving rules. For example, trials could last no longer than 1 day and time limits were put on speeches/testimony. Slave labor was used in the courts as well. The existence of these efforts suggests the time and costs were an issue the Athenians developed institutions to deal with.

See Carugati et al. (2015) for a discussion of the ability of the Athenians to maintain social order without using formal, centralized institutions.

See Fleck and Hanssen (2012) for a discussion of the lack of expertise in the Athenian legal system. They briefly discuss arbitration in Classical Athens, but talk about the informal mechanism of selecting a private mediator, rather than using the formal system described here.

In a surviving court case, an appeal of an arbitration decision is preserved (Against Meidias, XXII). In it, proper procedures are claimed to be violated and the jurors of the trial court were asked to rectify the conflict.

These are strong assumptions, but are common in the literature. For an overview and discussion see McCannon (2015).

Again, this is a simplifying assumption made for convenience. The main result can be extended if differences in the competence technology is introduced.

Obviously, n is an integer. I employ the notation for ease of presentation. An increase in the number of people, holding constant each person's competence, improves the group's improves accuracy.

Therefore, my modeling approach is closer to Buchanan and Tullock (1962) who also consider collective decision making. They investigate the optimal voting threshold, which balances the internal costs and the external costs. I, instead, focus on the number of people making the decision.

For example, if dρ/dε → − ∞ as ε → 0, then the Intermediate Value Theorem guarantees an equilibrium. See McCannon and Walker (2016) for a theoretical model exploring collective decision making when competence is endogenous.

It is, of course, possible that the LHS of (4) is increasing, since it combines a positive and negative term. The results require that the mechanism is on the downward sloping portion of the curve. In the context of arbitration this assumption is defensible. Elderly citizens were utilized as arbitrators. Adding more of them has a low opportunity cost. Juries, on the other hand, that use prime aged, productive citizens can be expected to have a high marginal cost.

References

Bergh, A., & Lyttkens, C. H. (2014). Measuring institutional quality in ancient Athens. Journal of Institutional Economics, 10(2), 279–310.

Boland, P. J. (1989). Majority systems and the Condorcet jury theorem. Statistician, 38(3), 181–189.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Carugati, F., Hadfield, G., & Weingast, B. (2015). Building legal orders in ancient Athens. Journal of Legal Analysis, 10(4), 150–173.

Congleton, R. D. (2007). Informational limits to democratic public policy: The jury theorem, yardstick competition, and ignorance. Public Choice, 132(3), 333–352.

D’Amico, D. J. (2010). The prison in economics: Private and public incarceration in ancient Athens. Public Choice, 145(3–4), 461–482.

D’Amico, D. J. (2018). The law and economics of sycophancy. Constitutional Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-018-9261-6.

Fleck, R. K., & Hanssen, F. A. (2006). The origins of democracy: A model with application to ancient Greece. Journal of Law and Economics, 49(1), 115–146.

Fleck, R. K., & Hanssen, F. A. (2009). “Rulers ruled by women”: An economic analysis of the rise and fall of women’s rights in ancient Sparta. Economics of Governance, 10(3), 221–245.

Fleck, R. K., & Hanssen, F. A. (2012). On the benefits and costs of legal expertise: Adjudication in ancient Athens. Review of Law & Economics, 8(2), 367–399.

Fleck, R. K., Hanssen, F. A. (2018). Endogenously determined versus exogenously imposed institutions: The case of tyranny in ancient Greece. Constitutional Political Economy (forthcoming).

Guha, B. (2011). Preferences, prisoners, and private information: Was Socrates rational at his trial? European Journal of Law and Economics, 31(3), 249–264.

Kaiser, B. (2007). The Athenian trierarchy: Mechanism design for the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economic History, 67(2), 445–480.

Kyriazis, N. (2009). Financing the Athenian state: Public choice in the age of Demosthenes. European Journal of Law and Economics, 27(2), 109–127.

Lyttkens, C. H., Tridimas, G., Lindgren, A. (2018). Making democracy work: An economic perspective on the Graphe Paranomon. Constitutional Political Economy (forthcoming).

MacDowell, D. M. (1978). The law in classical Athens. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Marselli, R., McCannon, B. C., & Vannini, M. (2015). Bargaining in the shadow of arbitration. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 117, 356–358.

McCannon, B. C. (2010a). Homicide trials in classical Athens. International Review of Law and Economics, 30(1), 46–51.

McCannon, B. C. (2010b). The median juror and the trial of Socrates. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 533–540.

McCannon, B. C. (2011). Jury size in classical Athens: An application of the Condorcet Jury Theorem. Kyklos, 64(1), 106–121.

McCannon, B. C. (2012). The origin of democracy in Athens. Review of Law & Economics, 8(2), 531–562.

McCannon, B. C. (2015). Condorcet Jury Theorems. In J. C. Heckelman & N. R. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of social choice and voting (pp. 140–160). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

McCannon, B. C. (2017). Who pays taxes? Liturgies and the Antidosis procedure in Ancient Athens. Constitutional Political Economy, 28(4), 407–421.

McCannon, B. C., & Walker, P. (2016). Endogenous competence and a limit to the Condorcet Jury Theorem. Public Choice, 169(1–2), 1–18.

Tridimas, G. (2011). The political economy perspective of direct democracy in ancient Athens. Constitutional Political Economy, 22(1), 58–82.

Tridimas, G. (2012a). How democracy was achieved. European Journal of Political Economy, 28, 651–658.

Tridimas, G. (2012b). Constitutional choice in ancient Athens: The rationality of selection to office by lot. Constitutional Political Economy, 23(1), 1–21.

Tridimas, G. (2015). War, disenfranchisement, and the fall of the Ancient athenian democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 38, 102–117.

Tridimas, G. (2016). Conflict, democracy, and voter choice: A public choice analysis of the Athenian ostracism. Public Choice, 169(1), 137–159.

Tullock, G. (1971). Public decisions as public goods. Journal of Political Economy, 79(4), 913–918.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCannon, B.C. Arbitration in classical Athens. Const Polit Econ 29, 413–423 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-018-9267-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-018-9267-0