Abstract

Pacific Islands often exemplify climate change vulnerability, yet little scholarship has probed how these representations translate to the media. This study examines newspaper articles about Pacific Islands and climate change in American, British, and Australian newspapers from 1999 to 2018, analyzing volume, content, and dominant narratives. These quantitative results are complemented by semi-structured interviews with journalists as well as Pacific stakeholders who engage with the media. Reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change focuses heavily on who and what are at risk from climate impacts; reporting on solutions is less frequent and dominated by discussions of migration. This overemphasis on vulnerability potentially downplays the importance of the resiliency and action of Pacific Island communities and positions the Pacific as a site for climate catastrophe, rather than climate justice. However, recent reporting may be moving away from overarching narratives of vulnerability, motivating continued research into these depictions and how they promote or discourage climate action.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Pacific Islands are often depicted as exemplars of climate change vulnerability (Barnett and Campbell 2015; Farbotko 2010): a contested position (e.g., McLean and Kench 2015) and yet one well supported by science (e.g., Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2018; Mimura et al. 2007). But what does it mean to be vulnerable—and why do these representations matter? The idea of vulnerability to climate change is itself a debated concept, ranging from a hazards school perspective that vulnerability is purely about biophysical risk, to a political economy perspective that vulnerability is a combination of social and “natural” factors (Bassett and Fogelman 2013). As demonstrated by debates over its definition, there is no single measurement or indicator of vulnerability (Hinkel 2011; Ford et al. 2010); thus, different representations of vulnerability become value-laden and used to motivate different actions and responses (O’Brien et al. 2007). Bankoff argues that these representations gain power through practices of colonialism and development; denoting large regions as vulnerable has been used as justification for Western intervention (Bankoff 2001). Similarly, several scholars have highlighted that constituting certain populations as vulnerable fails to account for community resilience and reifies historical power hierarchies (Farbotko 2005; Campbell 1997).

Research has also shown that, specifically for Pacific Islands and climate change, these different representations can influence public attitudes. Australian and American focus groups who were shown videos linking sea level rise in Kiribati and Tuvalu to consumption practices in the developed world expressed feelings of moral obligation because they connected sea level rise to their own position in the industrialized world (Cameron 2011). Thus, the way climate impacts in the Pacific are positioned affects how audiences conceptualize their own roles and obligation, and thus, perhaps, how they act in response.

These representations also impact Pacific Islanders; narratives of climate refugees and vulnerability may challenge their own conceptions of mobility and agency (Farbotko and Lazrus 2012). As explained by Farbotko and Lazrus, “in Tuvalu, migration can be considered a source of economic and social strength for Tuvaluans adapting to climate change in the long term, rather than, necessarily, a chronic ‘problem’ to be ‘solved’” (2012: 16). However, many Pacific Islanders, especially living on low-lying atolls, are considered to be on the “frontline” of climate change (Henry and Jeffery 2008), and representations of Pacific Islanders as the “first” climate refugees are used to “create an apparently visible embodiment of the effects of climate change” (Farbotko 2012: 123). This conflict between discourses of climate refugees and Tuvaluan conceptions of migration is inherently political, “producing new configurations of inequity” as island people are denied agency (Farbotko and Lazrus 2012: 16; Farbotko 2010). Thus, representations of Pacific Islands and climate change have social and political power; the use of Pacific Islands to “concretize climate science’s statistical abstractions” can be seen as a new form of eco-colonialism (Farbotko 2010: 58).

These representations do not just exist in the abstract—the media play an important role in producing and disseminating them. Research has demonstrated the powerful role of the media in public understanding of climate change (e.g., Anderson 2013; Sampei and Aoyagi-Usui 2009; Stamm et al. 2000); while people’s own experiences also shape how they conceptualize the world, news media are an important intermediary in that process (Olausson 2011; Carvalho 2010). This research has driven scholarship focused on media communication about climate change (MCCC); many quantitative and qualitative studies of media coverage of climate change have examined drivers of coverage (e.g., Schäfer et al. 2014; Schmidt et al. 2013), how climate change is framed (e.g., O’Neill et al. 2015; Nisbet 2009), the influence of journalistic norms (e.g., Boykoff and Boykoff 2007), the role of imagery (e.g., O’Neill and Nicholson-Cole 2009), and more.

News media have finite newspaper pages, so the amount of space dedicated to one topic necessarily displaces other topics. Research has shown broadly that issues that get more attention relative to others are more likely to seem important to audiences (Dearing and Rogers 1996) and specifically that attention to climate change in the media influences the general public’s awareness and knowledge (Sampei and Aoyagi-Usui 2009; Stamm et al. 2000). Beyond the general public, several studies have demonstrated that issue attention to climate change has an influence on political activities as well (e.g., Dolšak and Houston 2014; Walgrave et al. 2008). Furthermore, scholars have argued that the amount of coverage, rather than the content of that coverage, matters more for conveying the importance of environmental issues (e.g., Mazur 2009; Mazur and Lee 1993)—i.e., the fact that articles about climate change appear in news media is perhaps even more important than what they say and how they say it.

Few studies, however, have looked at issue attention or volume of coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change. An analysis of Samoan newspapers from 2008 to 2009 found few articles—often reliant on materials from other news agencies—published on climate change (Jackson 2010). In the same time period, media in four other Pacific newspapers and three UK newspapers had comparably limited coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change (Jackson 2010). In a similar study of The Fiji Times from 2004 to 2010, Chand found that while coverage of climate change was low, it had increased over that time period and, unlike coverage in Samoan newspapers, was most frequently original reporting rather than reprints of foreign media (2017). Thus, this study aims to contribute to this limited scholarship by characterizing how the volume and strength of focus of coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change has varied over time and between newspapers (RQ1).

However, beyond the mere existence of articles about Pacific Islands and climate change, the content and framing of those articles matter as well (e.g., Nisbet 2009), a topic similarly understudied for Pacific Islands. Climate change introduces many uncertainties—around causes, impacts, and the efficacy of solutions—so framings of climate change are vital to public understanding (Nisbet 2009), a claim that has also been validated experimentally by Spence and Pidgeon, who showed that different climate change frames (gain vs. loss outcomes; local vs. distant impacts) influenced perceptions about the severity of climate change and opinions about the appropriate actions in response (2010). The importance of framing has motivated MCCC research looking at many different types of frames—like climate change broadly (e.g., Wagner and Payne 2017), adaptation (Ford and King 2015), the forest-climate nexus (Kleinschmit and Sjöstedt 2014), and IPCC reports (O’Neill et al. 2015)—yet limited research has explored frames related to Pacific Islands and climate change. A discourse analysis of articles about Tuvalu in The Sydney Morning Herald found that Tuvaluan identity was often constructed in opposition to Australian stability and in connection to Tuvalu’s physical vulnerability (Farbotko 2005). More broadly, analysis of newspaper articles about Indigenous peoples and climate change found a similar tendency to portray Indigenous peoples as victims (Belfer et al. 2017). To expand on this scholarship, we aim to assess the relative presence of different narratives in reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change (RQ2).

2 Methods

2.1 Article selection

Despite growing evidence of the importance of television (e.g., Arlt et al. 2011) and social media (e.g., Newman et al. 2019) as sources of climate change information, MCCC research has focused disproportionately on print media (Schäfer and Schlichting 2014). While recognizing the importance of other media sources, newspapers were chosen for analysis firstly to aid a comparison with prior research on media representations on Pacific Islands and climate change (e.g., Farbotko 2005) and, secondly, because ease of access to several decades of archived newspaper articles made longitudinal analysis possible. Similarly, while media from Pacific Islands are under-researched (Schäfer and Schlichting 2014), limited data access makes analysis of changes over time difficult. Thus, this study aimed to characterize external representations of Pacific Islands and climate change to enable a more robust longitudinal analysis. Australia, the UK, and the USA were selected to capture a broad sample of English-language newspapers and for their current or colonial ties to islands in the Pacific region (Barnett and Campbell 2015).Footnote 1 In each country, two prominent broadsheet newspapers were chosen based on several criteria: a large circulation to provide insight into how the media helps to shape public perceptions, a long publication history to allow for analysis of temporal trends, prominence in MCCC literature (e.g., Schäfer et al. 2014; Schmidt et al. 2013) to facilitate comparisons with prior research, and substantive coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change. The newspapers selected are shown in Table 1.

For this study, media content was generated through purposive sampling, following Schäfer et al. (2016). Articles were accessed using the Factiva search engine and a broad Boolean search-stringFootnote 2 to locate potentially relevant articles over the two-decade period of January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2018.Footnote 3 The search string was designed to flag articles referencing climate change as well as Pacific Islands, either collectively or individually (focusing on Alliance of Small Islands States members in the Pacific region). This yielded 2379 articles for screening. These articles were then examined manually, and only those that mentioned Pacific Islands (or a specific Pacific Island) and climate change (directly or indirectly) together in at least one sentence were included, which gave us a final sample of 709 unique articles.

2.2 Coding

This project employed a combination of conventional and directed content analysis, drawing on Hsieh and Shannon (2005). The codebook was developed inductively but also informed by topics and theory in prior research on Pacific Islands and climate change. The codebook was broadly designed to investigate representations of vulnerability and agency in the context of Pacific Islands and climate change. This was assessed not only through the overall framing of the articles but also through a variety of different content categories: climate impacts, vulnerability, responses, politics, countries mentioned, and types of actors. The specific items coded are further enumerated in Sect. 3.

While a single coder analyzed the entire sample of articles, in order to verify intercoder reliability, a second coder also analyzed 10% of the sample. Intercoder reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa. Most elements had a very good strength of agreement (κ > .8), and those that did not still fell in the good strength of agreement range (κ > .6) based on the guidelines from Altman (1991). Statistical analyses were performed on coding data using SPSS.

2.3 Mixed methods approach

While the research questions introduced were explorable through the coding methods described above, we recognized that broader queries about why journalism is the way that it is and why these representations matter are important for contextualizing our results. To prevent this work from mirroring the journalistic structure we seek to comment on—essentializing narratives of climate change in the Pacific—we felt it necessary to include the voices of international and Pacific journalists who write about Pacific Islands and climate change, as well as Pacific stakeholders who engage with the media to better understand the experiences of people engaging with reporters as well as the journalistic drivers, constraints, and dominant narratives as articulated by those reporting.

We conducted semi-structured interviews, mainly over Skype, with nine international journalists, five Pacific journalists, and nine Pacific stakeholders (Table 2), and we conducted thematic analysis of these interviews using an abridged version of the methods described in Braun and Clarke (2006).Footnote 4 We were driven primarily by the text analysis findings, but used these interviews to add context and nuance to the numbers; as such, we integrate interview results in our discussion, rather than as a standalone subset of our results.

3 Codebook design

To address RQ1, each article was coded for the strength of focus on Pacific Islands and climate change. A brief mention was defined as Pacific Islands and climate change only mentioned in connection one time in the article, in a grouping of one to three sentences. Minor focus articles had several mentions of Pacific Islands and climate change, or a single longer section on the topic, but it was not the primary topic of the article. Main focus articles discussed Pacific Islands and climate change throughout the whole article.

To address RQ2, coders identified the dominant narrative in the portion of the article that talked about Pacific Islands and climate change (not the article overall). The narratives, developed inductively during the initial screening process, were no impact, vulnerability, solutions/responses, and contribution. No impact articles primarily depicted Pacific Islands as less vulnerable to climate change impacts than often suggested. Vulnerability articles talked mainly about Pacific Islands as uniquely at risk from the impacts of climate change. Solutions/responses articles described Pacific Islands as places where people are taking action and proposing or enacting solutions to climate impacts. Contribution articles depicted Pacific Islands as adding to global carbon emissions, through processes like deforestation.

To contextualize the narrative coding, we were also interested in capturing specific types of language around climate impacts, vulnerability, responses, and agency (shown in Table 3). Pacific Islands are already being affected, and will continue to be affected, by a range of climate impacts (e.g., Barnett and Campbell 2015; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2018; Mimura et al. 2007), making the discussion of particular impacts—beyond just broad references to climate change—a prevalent element of media representations of Pacific Islands and climate change. Therefore, we coded any mention of a specific climate impact in the Pacific, like sea level rise, ocean acidification, and drought. But there has been some contestation about the presence and severity of these impacts (e.g., McLean and Kench 2015), so we also coded for references to a lack of climate impacts in the Pacific. As explained by Barnett and Campbell, “in the discursive formation of climate change in SIDS, sea-level rise is the focus of attention, particularly as it may impact on atolls” (2015: 14). This has led to the perpetuation of the drowning or sinking island narrative—that certain islands will not just be affected by sea level rise, but will disappear forever (Farbotko 2010). We coded for instances of this type of language; while the actual terminology varied—sinking, drowning, being engulfed, disappearing, etc.—we only coded for instances evocative of the island no longer existing, rather than just being destroyed.

Language about drowning islands, while referring to the scientific phenomenon of sea level rise, becomes entangled with the broader notion of vulnerability: that people, things, and places are at risk from or already impacted by climate change. The codebook identified various types of vulnerability language (Table 3), based on categories created in a prior study of vulnerability language in The New York Times (Shea, in submission). While articles mentioned many forms of vulnerability, they also referenced many types of solutions and responses to climate impacts in the Pacific (Table 3). In light of scholarship on the growing role of Pacific activism (McNamara and Farbotko 2017), we were also interested in capturing how Pacific Islanders were given agency in these articles. The solutions in Table 3 were also further coded as either explicitly driven by Pacific Islanders or not, and we similarly coded articles for whether they included Pacific Islander voices, either directly or indirectly quoted.

4 Results

4.1 Summary of coverage

Overall, coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change was limited in the newspapers studied, but it has been increasing over time (see Fig. 1). Across the two-decade time period and the six newspapers, reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change represented only 0.0084% of total reporting and only 0.67% of climate change-related reporting (Shea et al., in submission). However, as shown in Fig. 1, there has been a noticeable shift in recent years. The Guardian, especially, saw a large jump in the number of articles published on Pacific Islands and climate change in 2015, and coverage in that outlet remained high in the subsequent years—likely a product of increased climate change coverage around the COP 21 climate summit in Paris, and a subsequent editorial priority on and investment of resources in climate change coverage. Similarly, issue attention—the proportion of Pacific Islands and climate change reporting in total reporting from each outlet—has been increasing.Footnote 5 Thus, while overall reporting remains limited, consistent with other studies of coverage in Pacific and international media (Chand 2017; Jackson 2010), there has been a noticeable recent uptick in the number of articles published; as shown in Fig. 1, nearly 40% of the reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change from 2015 to 2018 appeared in the Guardian, demonstrating the outlet’s disproporionate role in this recent rise in reporting.

However, most of this coverage does not engage substantively on the topic. Just over half of the coverage (53.3%, N = 378) only briefly mentioned Pacific Islands and climate change. Nearly one-third of the articles (30.9%, N = 219) had a minor reference to Pacific Islands and climate change. A minority of articles (15.8%, N = 112) had Pacific Islands and climate change as the main focus. While there was substantial year-to-year variation in these strength of focus proportions (see Fig. 1)—likely driven in large part by the relatively small number of articles published in a given year—since 2015, the proportion of main focus articles has been significantly higher than average at 20.4% (χ2(2) = 15.4, p < .001). While insufficient year-to-year numbers of articles prevent a more robust analysis of changes over time, this suggests that the increased volume of coverage since 2015 has also resulted in increased substantive engagement.

4.2 Dominant narratives

As shown in Fig. 2, the majority of articles used an overall vulnerability narrative, with few articles using no impact or contribution narratives (with the exception of The Australian, which had 12.1% no impact articles). Because no impact and contribution narratives occurred so infrequently, they were excluded from the statistical analysis of dominant narratives. News outlets varied significantly in their proportions of vulnerability and solutions/responses articles (N = 677; χ2(5) = 15.9, p = .007), with The Times having an especially high proportion of articles using a vulnerability narrative (87.5%, N = 42). The dominant narratives also varied significantly with strength of focus (χ2(2) = 7.8, p = .020); articles that mainly focused on Pacific Islands and climate change had a lower proportion of vulnerability narratives (56.2%, N = 59) than articles with a minor focus (62.2%, N = 130) or brief mention (69.7%, N = 253). Since 2015, the proportion of vulnerability narratives has significantly decreased in favor of solution/response narratives (χ2(1) = 19.0, p < .001).

4.3 Article elements

4.3.1 Impacts and vulnerability

As shown in Fig. 3, across the sample of articles, 55.4% (N = 393) mentioned specific climate impacts, such as sea level rise, ocean acidification, and storm surges. Conversely, 7.1% (N = 50) articles mentioned a lack of climate impacts, typically referencing science around atolls actually growing in elevation (e.g., McLean and Kench 2015). Over a quarter (26.7%, N = 189) of articles included language about drowning and sinking islands, which did not vary significantly across the different newspapers (χ2(5) = 8.2, p = 0.148).

Overall, 77.7% (N = 551) of articles contained vulnerability language. Individual countries were mentioned as vulnerable most frequently (38.4%, N = 272) followed by Pacific Islands as a group (29.3%, N = 208). People in Pacific Islands were also mentioned as vulnerable occasionally (22.0%, N = 156), followed by natural features (17.6%, N = 125), particular islands or atolls (9.3%, N = 66), and infrastructure (8.9%, N = 63). Despite decreases in overall vulnerability narratives since 2015, the presence of vulnerability language in articles has not changed significantly in the past 4 years (χ2(1) = .76, p = 0.385).

Figure 4 shows how various vulnerability elements tended to appear together, as calculated with a binary logistic regression. This figure highlights several interrelated divides in vulnerability language—broadly centered around differences in specificity. In articles that referenced Pacific Islands as a group as vulnerable, the probability of having language about particular countries being vulnerable decreased significantly; thus, within these more political vulnerability elements, there is a divide between articles using specific country language and articles using broader regional language. Similarly, articles that referenced particular countries or Pacific Islands as a group as vulnerable did not significantly co-occur with other vulnerability elements (with the exception of a weak association between particular countries and infrastructure)—highlighting a divide between articles using more general political terms and articles using more specific, localized vulnerability elements. At the same time, people, infrastructure, natural features, and particular islands vulnerability elements all tended to co-occur. These elements are the most specific and nuanced descriptions of vulnerability, suggesting that articles including one specific mention of vulnerability tended to include several others. However, the articles that used this more specific vulnerability language were less prevalent overall; countries and groups of countries were more commonly denoted as vulnerable than the people themselves.

Changes in probability of vulnerability elements. Table shows the change in the probability of a particular vulnerability element occurring in articles with another vulnerability element, as calculated with a binary logistic regression. Statistically significant cells are colored (p values in parentheses), with red indicating the strength of the increase of the co-occurrence of the elements and blue indicating the strength of the decrease of the co-occurrence of the elements

4.3.2 Climate futures/responses and agency

As shown in Fig. 3, in general, 61.4% (N = 435) of articles mentioned at least one solution or response. More specifically, 43.7% (N = 310) of articles mentioned at least one Pacific Islander-driven solution and 30.5% (N = 216) of articles mentioned at least one general solution. Migration was the solution mentioned most frequently (25.2%, N = 179), followed by international politics (24.4%, N = 173), financial support (13.5%, N = 96), and general mitigation (12.3%, N = 87). Adaptation (9.7%, N = 69) and mitigation in Pacific Islands (2.8%, N = 20) were both mentioned infrequently. Since 2015, the overall percentage of solutions mentioned has increased significantly (χ2(1) = 11.8, p = 0.001), driven largely by an increase in reference to Pacific Islander-driven solutions as mentions of general solutions remained relatively static.

While articles that mentioned at least one general solution did not vary significantly across news outlets (χ2(5) = 4.4, p = .494), articles that mentioned at least one Pacific Islander-driven solution did (χ2(5) = 24.4, p < .001). The New York Times and the Guardian had especially high proportions articles of with at least one Pacific Islander-driven solution (58.0%, N = 51 and 53.8%, N = 99, respectively). This is likely related to the increased proportion of international politics solutions referenced in these outlets—when international politics were mentioned in the context of Pacific Islands and climate change, it was often Pacific leaders advocating for solutions rather than more general mentions.

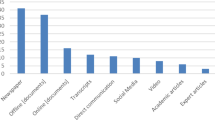

Thirty-eight percent of articles (N = 270) had at least one Pacific Island voice quoted (directly or indirectly) and 35% (N = 250) of articles had at least one general voice quoted—although only 13% (N = 91) had at least one of each type of actor. As shown in Fig. 5, government and UN officials were most commonly quoted, followed by scientists and academics. However, Fig. 5 demonstrates how these proportions varied between actors identified as Pacific Islander and other actors. Activists and campaigners were infrequently quoted across both populations. Likewise, additional coding of Pacific Island activism—any mention of specific protests or actions—was only referenced in 1.3% (N = 9) of the sample, with five mentions in the Guardian and two in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian respectively.

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary of reporting

In response to RQ1, our results show that coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change in all six newspapers was marginal—and most of that coverage only engaged with the topic in several sentences of an article—a fact that was noted in interviews with journalists and Pacific stakeholders alike (J8, PJ1, PJ2, S8). As contextualized by a Pacific NGO organizer:

“There’s a real lack of Pacific news in international news outlets. I mean, we hardly get mentioned … unless it’s a cyclone or an earthquake, you’re not going to see mention of the Pacific at all, which I think is a really big problem: a region that comprises 30% of the ocean EEZs [Exclusive Economic Zones] doesn’t receive more attention … There’s a real gap in just our stories being told and being acknowledged as people” (S8).

However, there has been a substantial increase in coverage volume since 2015, coupled with an increased percentage of main focus reporting—a phenomenon perceived by several interviewees who noted the influence of high-profile UNFCCC meetings, the growing role of China in the Pacific, and the rise of Pacific activism on coverage (J7, J9). Thus, while limited when compared to overall climate change coverage, the over 700 articles published in the six newspapers studied over the past two decades represent an important component of the discursive formation of Pacific Islands and climate change, a formation that is potentially beginning to change. The implications of the narratives in that discourse are further discussed in the subsequent sections.

5.2 Dominant narrative of vulnerability

In response to RQ2, our results show that across the sample, the majority of articles coded were identified as being primarily about vulnerability to climate impacts, a focus consistent with interview data from both journalists and Pacific stakeholders. As explained by an Australian journalist:

“I think there is still that kind of background, broad grand narrative around a kind of helplessness and incapacity that sort of contaminates a lot of reporting and diminishes the Pacific to a kind of passive entity to whom things are done…” (J9).

Several scholars have asserted that these rhetorical choices have power: downplaying community resilience, bolstering historical power hierarchies, and justifying Western intervention (e.g., Farbotko 2005; Bankoff 2001; Campbell 1997). Bankoff has argued “that tropicality, development and vulnerability form part of one and the same essentialising and generalising cultural discourse that denigrates large regions of world as disease-ridden, poverty-stricken and disaster-prone” (2001: 19). Bankoff’s argument is supported by our coding data on specific types of vulnerability language, which showed a divide between broad and specific vulnerability rhetoric—painting the entirety of the Pacific as vulnerable lends more power to the eco-colonial project than discussing a particular village or community. That this tendency bleeds into reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change was noted in several interviews (J6, J9, PJ2, S7). As one Australian journalist explained:

“There is still, I reckon, infecting a lot of Pacific reportage, a kind of degree of—colonialism is probably too strong—but it’s the vestigial sort of idea around it that, you know, these are benighted countries that need our help and those sorts of things. It’s not Kipling’s White Man's Burden, but there is an almost paternalistic attitude towards it” (J9).

A similar paternalism was found by Farbotko in her analysis of how Tuvalu was positioned in relation to Australia in The Sydney Morning Herald articles (2005). Overall, our analysis demonstrates that vulnerability language was highly prevalent in the sample of articles studied, but furthermore, that the particular clusters of vulnerability elements—linked by specificity of language—square with both interview data and prior scholarship on representations of vulnerability.

However, it is important to note that as the volume of coverage has been increasing over the past 4 years, the presence of vulnerability language has remained relatively constant while the proportion of overall vulnerability narratives has decreased. This suggests that while language about vulnerability to climate change is enduring, the way it is framed in articles may be shifting.

5.3 Climate impacts and drowning island language

Language about climate impacts, and drowning islands specifically, was highly prevalent in the sample of articles (Fig. 3), representing a less explicit and more scientifically infused notion of vulnerability. That this particular rhetoric has gained traction across populations both proximate to and distant from the Pacific seems a testament to the power of rendering climate impacts both visible and existential. Many interviewees acknowledged that while there are other, perhaps even more pressing, climate impacts in the Pacific, sea-level rise is particularly impactful because it can be shown clearly through photos and videos (J4, J7, J8, J9, S5). But beyond simply providing a compelling visual, as explained by Farbotko, the disappearing island comes to signify “the scale and urgency of uneven impacts of climate change” (2010: 47), making it an important tool for demonstrating the stakes of inaction.

But there is a conflict between the power of drowning island language as a journalistic tool for highlighting climate impacts and the implications of those representations. Several journalists interviewed highlighted feelings of tension—both with the Pacific Islanders they interviewed and with editors (J5, J6). An American journalist who reported from Kiribati noted that people he talked to seemed resentful of the interest in the drowning island story, that “the international media only pays attention to them in this context of doom” (J5). But conversely, a British journalist who reported from Tuvalu described pressure to tell the more dramatic “drowning island” story:

“I do remember that sort of tension of distant editors in London assuming that this story was sort of happening, instantaneously, you know, in sort of, in the next couple of years, this nation was going to be underwater. And clearly, it wasn't like that. And the science wasn't showing that. But because of this idea of the resettlement had already started, there was that … that sort of that sort of drama about it”(J6).

As demonstrated through the work of Farbotko, however, and emphasized by many of the interviewees (J1, J2, J3, PJ1, PJ2, S2, S4, S7, S9), these representations also deprioritize Pacific perspectives and lived experiences, which do not always fit so neatly into the dramatic drowning island narrative (Farbotko and Lazrus 2012; 2010). A Pacific politician described the tension between the truth of the disappearing island narrative and the problems with how it is often wielded, emphasizing the dehumanizing nature of the narrative:

“The reality of the issue in Tuvalu is that islands are sinking, but we do not want to use that … to be pitied by the international community … I believe that there should be another term used by the journalists: instead of focusing on sinking islands, focus on the survival of the people. Because, you know, when we talk about sinking island, we are talking about a surface, a land surface out of the blue ocean. It does not reflect the reality of what will disappear when it comes to the time” (S7).

Thus, the types of climate impacts portrayed, and the particular language used, often have conflicting implications for newspaper audiences and Pacific peoples—as a tool not only for rendering climate change visible and urgent but also for downplaying human experiences and lived realities in coverage of Pacific Islands.

5.4 Pacific Island futures: agentic or inevitable?

Discussions of solutions and responses have a more complex relationship with the overall narrative of vulnerability. On one hand, narratives about solutions champion agency in the face of climate risks, but on the other, they may reinforce the idea that impacts in Pacific Islands are indeed existential. In general, reporting on solutions aligned with the desires of the Pacific stakeholders interviewed, who advocated for more stories about responses to climate impacts instead of emphasizing vulnerability. As explained by one Pacific stakeholder, “the narrative has been too romanticized by the media: that the interest is mostly on what is happening rather than on finding solutions” (S7). However, there was some discrepancy among interviewees over what kinds of solutions the media should be covering, with some calling for more stories about Pacific Islanders as agents (J8, PJ1, S3, S4, S5, S9), and others emphasizing that the developed world should be called to action (S3, S4, S7, S8). One Pacific stakeholder described the interplay of these desires:

“So rather than seeing the Pacific as victims, the focus should be on the perpetrators and what they can do to address the problem … A lot of Pacific leaders and a lot of Pacific people are doing what they can to build resilience and to have our own transition to renewable energy. And we'd love to see bigger countries doing the same and taking responsibility and acknowledging the impact that they're having” (S8).

While the general reporting on solutions was consistent with desired representations expressed by interviewees, the large focus on migration (see Fig. 3) was not. Many Pacific stakeholders expressed discontent at the prevalence of the migration narrative as one that, although forward-looking, denies agency to Pacific Islanders who do not want to leave their homes (S2, S3, S4, S7, S8, S9). Furthermore, in their descriptions, several interviewees categorized migration as separate from solutions (S4, S9); one Pacific Island stakeholder said, “people should talk about solutions: that these people are happy where they are, they are contented where they are, and we should help them to remain where they are”—rendering migration outside of the scope of “solutions” (S9). Thus, while solutions and responses were present in over 60% of the articles sampled, the fact that migration was the most commonly mentioned response suggests that there is often still some element of vulnerability inherent in the discussion of Pacific Island futures.

However, more articles contained at least one Pacific Islander-driven solution than contained at least one general solution, suggesting that within this coverage, Pacific Islanders are being given agency to define their preferred future action. Similarly, Pacific Islanders were quoted in articles more than other actors. Yet the vast majority of Pacific Island actors were identified as government or UN officials—with few activists and NGO representatives quoted—suggesting that politics, rather than activism and grassroots work, underpin the discursive formation of Pacific futures (Fig. 4).Footnote 6 The lack of coverage of activism in relation to Pacific Islands and climate change is especially notable given its rising prominence. In their analysis of the Pacific Climate Warriors, a network of young Pacific Islanders from a number of nations connected to the global climate action group 350.org, McNamara and Farbotko argue that these activists are “re-envisioning Pacific futures in new ways” and “refusing to accommodate ideas of Pacific Islanders as destined to be passive victims of climate change” (2017: 23). Yet our analysis suggests that these futures have not simultaneously been re-imagined and re-negotiated in international media.

5.5 Journalistic constraints

As evidenced in interview data, none of these choices about content and narratives exist in a vacuum. Most broadly, journalists and Pacific stakeholders alike commented on the challenge of moving past preconceived notions of Pacific Islands and climate change (J4, J7, J9, PJ1). As several journalists noted that Pacific Island stories get told at some level because of journalistic mimicry—that one instance of successful field reporting in a context such as Tuvalu encourages other journalists to pursue similar stories—this becomes an almost self-fulfilling prophecy, with future journalists heavily informed by the narratives told previously (J1, J9). Many journalists interviewed noted the role of editors, who are often expecting a particular sort of story, in this representational tension (J1, J2, J6, J7, J8).

However, the interview data also highlighted several more pragmatic themes around challenges: cultural, financial, and logistical. Journalists reflected on the lack of homogeneity across Pacific cultures, and the challenges of being an outsider with limited context (J1, J4, J5, J9, PJ2). They also emphasized how expensive it is to travel to the Pacific to do field reporting—both in terms of airfare and in time lost for other reporting (J2, J4, J7, J8, J9, PJ1, PJ2, PJ3). Furthermore, they highlighted difficulties on the ground: connecting with sources, traveling to remote locations, Wi-Fi connectivity, etc. (J1, J2, J5, J7, J9, PJ1, PJ2, PJ3). These pragmatic challenges contribute to what many interviewees described as fly-in, fly-out reporting, or parachute journalism—where reporters come in for only a short time, grab the story they need, and go (J1, J3, J4, PJ2, S1). Although this is a reality, at some level, of the current media climate, many journalists were frustrated by it (J1, J3, J4, PJ3). As explained by one American journalist, “when people bounce in and out like that, they get the story they want. They don’t necessarily get the story that’s, I don’t know, that’s most helpful to the actual people” (J3).

6 Conclusions

Overall, reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change in the American, British, and Australian newspapers studied has been sparse and heavily focused on vulnerability, both in individual content elements and in the overarching narratives. Yet, a majority of articles do still mention solutions and responses—however entangled with notions of victimhood—and many give voice to Pacific Island actors. Furthermore, this coverage has been changing in the past 4 years, with recent articles focusing more on solutions than on vulnerability and including more substantive reporting.

This analysis is not intended to ascribe a moral or ethical judgment on the way reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change has been conducted; as contextualized by interviews, there have certainly been negative examples of such reporting, but they exist in a challenging media landscape that constrains journalists. However, these representations of Pacific Islands are not inconsequential: as shown in interviews and prior scholarship, the way Pacific stories are told has implications for both international audiences and Pacific Islanders themselves.

Little scholarship exists on reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change, and this study aims to provide a more robust baseline for analysis. But this work is still limited by its focus on newspaper reporting, selection of newspapers, and particular codebook design. Future work might expand the corpus analyzed—looking at radio, television, or social media—and more clearly link article elements coded and their complex relationship with broader narratives of vulnerability and agency. In addition, the small year-to-year sample size in this study prevented robust analysis over time—yet several interviewees perceived that reporting on climate impacts in the Pacific has been changing, especially in the past several years with high-profile UNFCCC meetings, the growing role in China in the Pacific, and the rise of Pacific activism (J7, J9). An understanding of how the patterns identified in this study have changed over time would provide even more relevant commentary on coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change.

While reporting on Pacific Islands and climate change may already be shifting, interviewees highlighted several distinct strategies for ensuring future reporting continues to move away from representations of vulnerability. For one, collaboration with, and republishing of, Pacific journalists contributes to regional capacity-building and gives enhanced opportunities for Pacific Islanders to construct their own narratives (J9, PJ1, PJ2, PJ3, PJ4, S3, S5). When international journalists are telling stories about the Pacific, the model of private or philanthropic funding can help to mitigate the negative aspects of fly-in, fly-out reporting—giving journalists additional resources to prolong their Pacific reporting and gather more nuanced perspectives (J1, J2, J9). Consulting with Pacific stakeholders, especially those quoted or interviewed, before publishing articles can help ensure that representations feel fair and accurate (J4, S1, S8, S9).

Pacific Island nations are often positioned as emblems of climate vulnerability, yet this characterization undermines the resiliency and willpower of Pacific peoples and governments in the face of climate impacts. As Pacific stakeholders continue to advocate for climate justice, it is crucial to devote further attention to the role the media play in representations of Pacific Islands and climate change.

Notes

Only three countries were selected so that it would be possible to code all relevant articles from each country. However, New Zealand similarly fulfills these criteria and future studies might consider extending analysis to New Zealand, in particular.

(Climat* Change* OR Global Warming* OR Greenhouse Effect*) AND (Pacific Island* OR Pacific atoll* OR Melanesia* OR Polynesia* OR Cook Islands* OR Micronesia* OR Fiji* OR Kiribati* OR Vanuatu* OR Marshall Islands* OR Tuvalu* OR Nauru* OR Niue* OR Palau* OR Papua New Guinea* OR Samoa* OR Solomon Islands* OR Tonga*)

This time period was constrained by the lack of archived articles in Factiva for several of the study newspapers before 1999, but coverage of Pacific Islands and climate change in available newspapers before 1999 was also sparse. The two-decade time period is also consistent with other long-term MCCC studies (Belfer et al. 2017; Ford and King 2015)

Initial codes were generated from familiarity with the data from the interview and transcription process and were also informed by the preliminary results of the newspaper content analysis. After coding all of the interviews, codes were grouped into overarching themes, which helped the interview content to align with the content analysis.

For a more detailed analysis of issue attention, see Shea et al. (in submission).

For more on this, see Shea et al. (in submission).

References

Altman DG (1991) Practical statistics for medical research, 1st edn. Chapman and Hall, London; New York

Anderson A (2013) Media, culture and the environment. Routledge, London

Arlt D, Hoppe I, Wolling J (2011) Climate change and media usage: effects on problem awareness and behavioural intentions. Int Commun Gaz 73(1–2):45–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048510386741

Bankoff G (2001) Rendering the world unsafe: ‘vulnerability’ as Western discourse. Disasters 25(1):19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00159

Barnett J, Campbell JR (2015) Climate change and small island states: power, knowledge and the South Pacific, 1st edn. Routledge, Oxford

Bassett TJ, Fogelman C (2013) Déjà vu or something new? The adaptation concept in the climate change literature. Geoforum 48:42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.010

Belfer E, Ford JD, Maillet M (2017) Representation of indigenous peoples in climate change reporting. Clim Chang 145(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-2076-z

Boykoff MT, Boykoff JM (2007) Climate change and journalistic norms: a case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum 38(6). Theme Issue: Geographies of Generosity):1190–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.01.008

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cameron FR (2011) Saving the ‘disappearing islands’: climate change governance, Pacific island states and cosmopolitan dispositions. Continuum 25(6):873–886. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2011.617879

Campbell JR (1997) Examining Pacific Island vulnerability to natural hazards. In: Planitz A, Chung J (eds) Proceedings, VIII Pacific Science Inter-Congress. United Nations Department for Humanitarian Affairs, South Pacific Programme Office, Suva, pp 53–62

Carvalho A (2010) Media(ted) discourses and climate change: a focus on political subjectivity and (dis)engagement. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 1(2):172–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.13

Chand S (2017) Newspaper coverage of climate change in Fiji: a content analysis. Pac Journal Rev 23(1):169. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v23i1.310

Dearing JW, Rogers EM (1996) Communication concepts 6: agenda-setting. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Doherty B (2015) Labor champions plan to resettle Pacific climate change migrants. The Guardian, 10 November

Dolšak N, Houston K (2014) Newspaper coverage and climate change legislative activity across US states. Global Policy 5(3):286–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12097

Farbotko C (2005) Tuvalu and climate change: constructions of environmental displacement in the Sydney Morning Herald. Geogr Ann Ser B Hum Geogr 87(4):279–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00199.x

Farbotko C (2010) Wishful sinking: disappearing islands, climate refugees and cosmopolitan experimentation. Asia Pac Viewp 51(1):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.001413.x

Farbotko C (2012) Skillful seafarers, oceanic drifters or climate refugees? Pacific people, news value and the climate refugee crisis. In: Moore K, Gross B, Threadgold T (eds) Migrations and the media. Global crises and the media, vol 6. Peter Lang, New York, pp 119–142

Farbotko C, Lazrus H (2012) The first climate refugees? Contesting global narratives of climate change in Tuvalu. Glob Environ Chang 22(2):382–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.11.014

Flannery T (2005) Our civilisation faces its darkest hour. We must act now against global warming. The Sydney Morning Herald, 24 September

Ford JD, King D (2015) Coverage and framing of climate change adaptation in the media: a review of influential North American newspapers during 1993–2013. Environ Sci Pol 48:137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.12.003

Ford JD, Keskitalo ECH, Smith T et al (2010) Case study and analogue methodologies in climate change vulnerability research. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 1(3):374–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.48

Henry R, Jeffery W (2008) Waterworld: the heritage dimensions of ‘climate change’ in the Pacific. Hist Environ 21(1):12–18

Hinkel J (2011) “Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity”: towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Glob Environ Chang 21(1):198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.08.002

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jacob D, Taylor M, et al. (2018) Impacts of 1.5°C of global warming on natural and human systems. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, et al. (eds) Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (In Press.): 138

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Ives M (2016) Remote Pacific nation, threatened by rising seas. The New York Times, 3 July

Jackson C (2010) Staying afloat in paradise: reporting climate change in the Pacific. Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford. 36

Keating J (2018) The sinking state. Wash Post, 29 July

Kleinschmit D, Sjöstedt V (2014) Between science and politics: Swedish newspaper reporting on forests in a changing climate. Environ Sci Pol 35:117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.02.011

Kristof ND (2006) A paradise drowning. The New York Times, 8 January

Lyons K, Doherty B (2018) Australia relationship with Pacific on climate change ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘abusive’. The Guardian, 5 September

Maher S (2008) Greenhouse deals `beat carbon trading’. The Australian, 25 March

Mathiesen K (2015) Losing paradise: the people displaced by atomic bombs, and now climate change. The Guardian, 9 March

Mazur A (2009) American generation of environmental warnings: avian influenza and global warming. Hum Ecol Rev 16(1):17–26

Mazur A, Lee J (1993) Sounding the global alarm: environmental issues in the US national news. Soc Stud Sci 23(4):681–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631293023004003

Mcdonald H (2000) Lying low. The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November

McLean R, Kench P (2015) Destruction or persistence of coral atoll islands in the face of 20th and 21st century sea-level rise? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 6(5):445–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.350

McNamara KE, Farbotko C (2017) Resisting a ‘doomed’ fate: an analysis of the Pacific climate warriors. Aust Geogr 48(1):17–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2016.1266631

Milman O, Watts J and Phillips T (2017) Worried world urges Trump not to pull out of Paris climate agreement. The Guardian, 7 May

Mimura N, Nurse L, McLean R et al (2007) Small islands. In: Parry ML, OF C, Palutikof JP et al (eds) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 687–716

Minchin L (2006) Going under. The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 August

Morin R, Deane C (2001) Channel surfing brings birth of think tank. Wash Post (27 November)

Newman N, Fletcher R, Kalogeropoulos A et al (2019) Digital news report 2019. Reuters Institute 156

Nisbet MC (2009) Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev 51(2):12–23. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

O’Brien K, Eriksen S, Nyggard LP et al (2007) Why different interpretations of vulnerability matter in climate change discourses. Clim Pol 7(1):73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2007.9685639

O’Neill S, Nicholson-Cole S (2009) “Fear won’t do it”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci Commun 30(3):355–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

O’Neill S, Williams HTP, Kurz T et al (2015) Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC Fifth Assessment report. Nat Clim Chang 5(4):380–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2535

Olausson U (2011) “We’re the ones to blame”: citizens’ representations of climate change and the role of the media. Environ Commun 5(3):281–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2011.585026

Sampei Y, Aoyagi-Usui M (2009) Mass-media coverage, its influence on public awareness of climate-change issues, and implications for Japan’s national campaign to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Glob Environ Chang 19(2):203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.005

Schäfer MS, Schlichting I (2014) Media representations of climate change: a meta-analysis of the research field. Environ Commun 8(2):142–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2014.914050

Schäfer MS, Ivanova A, Schmidt A (2014) What drives media attention for climate change? Explaining issue attention in Australian, German and Indian print media from 1996 to 2010. Int Commun Gaz 76(2):152–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048513504169

Schäfer MS, Berglez P, Wessler H et al (2016) Investigating mediated climate change communication: a best-practice guide. Res Rep 2016(6):6. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-131746

Schmidt A, Ivanova A, Schäfer MS (2013) Media attention for climate change around the world: a comparative analysis of newspaper coverage in 27 countries. Glob Environ Chang 23(5):1233–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.020

Spence A, Pidgeon N (2010) Framing and communicating climate change: the effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Glob Environ Chang 20(4):656–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.002

Stamm KR, Clark F, Eblacas PR (2000) Mass communication and public understanding of environmental problems: the case of global warming. Public Underst Sci 9(3):219–237. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/302

The Australian (2010) Faith is always inferior to facts. 27 July

Wagner P, Payne D (2017) Trends, frames and discourse networks: analysing the coverage of climate change in Irish newspapers. Ir J Sociol 25(1):5–28. https://doi.org/10.7227/IJS.0011

Walgrave S, Soroka S, Nuytemans M (2008) The mass media’s political agenda-setting power: a longitudinal analysis of media, parliament, and government in Belgium (1993 to 2000). Comp Pol Stud 41(6):814–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006299098

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Spencer Dunleavy and Joshua Carter for guidance on statistical methods, to Silje T. Kristiansen for demonstrating best practices in codebook design and SPSS data organization, and to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. Endless gratitude is given to all journalists and stakeholders who agreed to be interviewed for this project.

Funding

Research for this project was supported by grants from the School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford; Green Templeton College, University of Oxford; and the Rhodes Trust (Sir Peter Elworthy and Warden’s Discretionary Fund grants).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.S. designed the study, conducted interviews, coded article and interview data, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. J.P. provided guidance on study design and implementation and reviewed drafts of the paper. S.O. coded a subset of articles so that intercoder reliability could be calculated and reviewed drafts of the paper.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shea, M.M., Painter, J. & Osaka, S. Representations of Pacific Islands and climate change in US, UK, and Australian newspaper reporting. Climatic Change 161, 89–108 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02674-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02674-w