Abstract

Change and variability in the timing and magnitude of sea ice geophysical and thermodynamic state have consequences on many aspects of the arctic marine system. The changes in both the geophysical and thermodynamic state, and in particular the timing of the development of these states, have consequences throughout the marine system. In this paper we review the ‘consequences’ of change in sea ice state on primary productivity, marine mammal habitats, and sea ice as a medium for storage and transport of contaminants and carbon exchange across the ocean-sea-ice-atmosphere interface based upon results from the International Polar Year. Pertinent results include: 1) conditions along ice edges can bring deep nutrient-rich ‘pacific’ waters into nutrient-poor surface waters along the arctic coast, affecting local food webs; 2) both sea ice thermodynamic and dynamic processes ultimately affect ringed seal/polar bear habitats by controlling the timing, location and amount of surface deformation required for ringed seal and polar bear preferred habitat 3) the ice edges bordering open waters of flaw leads are areas of high biological production and are observed to be important beluga habitat. 4) exchange of climate-active gases, including CO2, is extremely active in sea ice environments, and the overall question of whether the Arctic Ocean is (or will be) a source or sink for CO2 will be dependent on the balance of competing climate-change feedbacks.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and rationale

Extraordinary changes are currently underway in the arctic sea ice cover which will have consequences throughout marine and terrestrial systems. The Arctic has recently experienced unprecedented variability in both the rates and magnitudes of change in the cryosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere and lithosphere, with implications for ecosystem functioning, increased industrial development, and concomitant globalization of local economies. These changes are challenging our ability to respond as a polar nation and to develop a coordinated and scientifically-informed policy for the Arctic.

General circulation models have, for many years, indicated that we should expect a polar amplification of a global increase in temperature (IPCC 2007). Several studies show that this amplification is clearly underway and that the Arctic is experiencing a magnification in surface temperature that is approximately three times greater than the global average (ACIA 2005). Climate change has immediate implications for marine ecosystem function and services, the health and well-being of local residents and their economies, and the sustainability of northern communities. Creative responses based on sound research, shared knowledge and the engagement of people at all levels is required to meet this critical challenge.

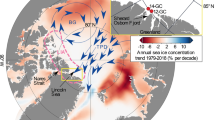

Observations indicate that the Arctic Ocean and its peripheral seas are presently warming. The extent of arctic sea ice has shrunk at an average annual rate of about 45,100 km2 (±4,600 km2) per year from 1979 to 2006 (Parkinson and Cavalieri 2008). Five of the lowest summer sea ice extents have occurred since 1998, with 2007 and 2011 being the lowest minima on the instrumental record. The thickness of the multiyear ice has also decreased by about 40 % over the past 30 years (Rothrock et al. 1999; Liu et al. 2004). Recent studies have documented variations in the Arctic Oscillation and associated surface atmospheric pressure fields (Thompson and Wallace 1998). The resulting strengthening of westerly winds has deflected eastward the freshwater plumes of the several large rivers, and has increased the export of sea ice through the transpolar drift stream (Kwok 2008). The freshwater on the continental shelves normally forms a shield between the ice and the underlying warm atlantic water. The eastward advection of this shield has allowed contact between the ice and increasingly warmer invading atlantic waters (Polyakov et al. 2005), thus potentially enhancing sea-ice melt. In the Canada Basin, the Beaufort Gyre also affects reduction of sea ice and formation of the flaw lead system. Recent results (Lukovich and Barber 2006) show that the reversal of the Beaufort Gyre, triggered by increased cyclogenesis over the Canada Basin (Zhang et al. 2004), has increased in frequency since 1990, thereby affecting both sea-ice extent and dynamics.

Flaw leads and polynyas are particularly important physical features in the arctic marine system, and provide a unique environment from which we can gain insights into the changing polar marine ecosystem. Oceanographically, the high ice production in the flaw lead contributes significantly to brine fluxes from the continental shelves into the deep basins (Martin et al. 1995). These fluxes drive biogeochemical fluxes on and off the continental shelves, and control many aspects of gas and other mass fluxes across the ocean-sea-ice-atmosphere interface. Meteorologically, we expect the flaw lead system to play a central role in steering cyclones within the area; we also expect that its connection to the central sea ice pack signifies a large-scale teleconnection to hemispheric scale pressure patterns such as the Arctic Oscillation (e.g., Dmitrenko et al. 2005).

Sea ice controls the exchange of heat, moisture and gas across the ocean-sea-ice-atmosphere interface due to its high surface albedo and low thermal conductivity. Because of this control, sea ice plays a central role in how the marine ecosystem responds to (and affects) climate change. It controls the distribution and timing of light to the euphotic zone in the upper ocean, including light to the base of the ice where early primary production occurs. Sea ice also controls the exchange of heat and moisture with the atmosphere thereby linking directly to feedbacks that affect sea ice. Biologically, the circumpolar flaw lead preconditions the shelves to be productive portions of the marine ecosystem with the early availability of light and increased availability of nutrients through advection and upwelling at the shelf break. We expect ecosystem-wide enhancements to productivity in these areas, sustained for longer periods throughout the annual cycle. These expectations are supported by early use of the flaw lead by apex predators such as birds, beluga, narwhal, bowhead whales, and polar bears. It is also evidenced by the historical use of polynyas by Inuit.

The objectives of this paper are to provide a review and summary of research results from several projects of the International Polar Year (IPY) that contained a significant component of sea ice research focused specifically on the ‘consequences’of observed change and variability in sea ice on the marine ecosystem. A companion paper presents results associated with the magnitude of the ‘observed change’ and the ‘causes’ of this change in sea ice (Barber et al. 2012; this issue). A more detailed assessment of the entire marine ecosystem, both ice associated and open water associated, is presented for nutrients and primary production in Tremblay et al. (2012; this issue) and for secondary production and biodiversity in Darnis et al. (2012; this issue). Here we present only those elements of biogeochemistry and marine ecosystem function that are uniquely connected to sea ice (i.e., caused by or respond to changes in sea ice).

2 Sea ice and ecosystems

Large seasonal fluxes in temperature, light and sea ice extent are integral aspects of the arctic marine environment. This environment is undergoing unprecedented changes in response to our warming climate, with a recent accelerated decline in sea ice cover (Stroeve et al. 2011), rapid deterioration of perennial (multi-year) sea ice (Barber et al. 2009) and changes to water mass characteristics and distribution (Polyakov et al. 2005). Connection of the ice-covered marine ecosystem to the warming arctic environment is readily apparent, including a potential increase of phytoplankton production associated with an increasing ice-free period (Rysgaard et al. 1999; Arrigo et al. 2008). However, the extent of these changes and future changes on the ice-associated ecosystem and associated climate feedback processes are not well understood. Polynyas and ice edges are known to have higher species abundances than surrounding ice-covered waters (Stirling 1980; Dunbar 1981; Stirling 1997) and are particularly important in spring as migrating animals arrive (Stirling 1997).

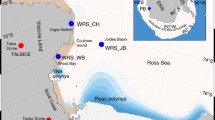

One of the goals of the International Polar Year Circumpolar Flaw Lead (IPY-CFL) system study (Barber et al. 2010) was to better understand the role of sea ice in controlling the physical (e.g., light and temperature) and chemical (e.g., nutrient) factors influencing ice-associated primary production within the study area (Fig. 1). These key factors, which determine growth and accumulation of ice algae and under-ice phytoplankton, are particularly sensitive to changes associated with a warming climate. At higher trophic levels, we also aimed to evaluate the importance of the circumpolar flaw lead to marine mammals in the eastern Beaufort Sea and to polar bear use of sea ice habitats.

2.1 Sea ice and upwelling

Earlier and larger open water areas in the Amundsen Gulf will increase atmosphere–ocean coupling, with the potential to bring nutrient-rich pacific waters, typically observed at depths greater than 100 m in the Canadian Beaufort Sea, to the surface where they can be rapidly utilized by primary producers (Mundy et al. 2009). As a result of changing ice conditions, more upwelling events may occur on a regular basis across the arctic coastal zone where new hot spots of primary production could develop, affecting the local pelagic and benthic food web (Forest et al. 2011; Link et al. 2011). Of particular note was an upwelling-induced phytoplankton bloom observed in early June 2008 at the edge of landfast ice in the IPY-CFL region (Fig. 2). Over a 3-week period, this event was shown to contribute more than two times the annual primary production previously estimated for the region (Mundy et al. 2009). This substantial increase is likely attributable to the high acclimation capacity of some phytoplankton communities that allow them to take advantage of nutrient pulses associated with upwelling events. In an environment where upwelling events are expected to become more regular, notably in areas adjacent to sea ice cover where light is limited, species with such a capacity would be favoured (Palmer et al. 2011). This positive response to upwelling events was observed not only for under-ice phytoplankton but also for bottom ice algae along the ice edge and phytoplankton in the open waters of the Amundsen Gulf. Indeed, ice algal biomass along the ice edge was more than three times that reported over the last 35 years in the Beaufort Sea (Tremblay et al. 2011) and phytoplankton production in Amundsen Gulf was 3–5 times higher in summer 2008 than in summer 2004 (Sallon et al. 2011).

An image of the landfast ice edge study site in Darnley Bay obtained from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard NASA’s Terra satellite (a); a feather plot of hourly averaged wind vectors obtained from the meteorological tower on the CCGS Amundsen (b); and interpolated time series of temperature, salinity, nitrate concentration, and chlorophyll a concentration, observed at the Darnley Bay sampling station (c). The shaded regions in (b) and (c) denote the period of sustained strong winds that resulted in the upwelling event (Adapted from Mundy et al. 2009)

In a joint IPY-CFL/ArcticNet study, the influence of environmental factors on the structure and function of phytoplankton communities in the Canadian High Arctic was investigated (Ardyna et al. 2011). The Beaufort Sea and central Canadian Arctic Archipelago were categorized as oligotrophic waters, in contrast to the eastern Canadian Arctic Archipelago and Baffin Bay regions, as well as the centre of the Amundsen Gulf, which were found to be more eutrophic. Compiling 7 years of chlorophyll a concentration data split into these different regimes revealed that phytoplankton biomass increased significantly in the euphotic zone, associated with decreasing ice cover in both eutrophic and oligotrophic waters (Fig. 3). However, the relationship was weaker with a much smaller slope for oligotrophic waters. The results suggest that decreasing ice cover, and consequently a longer growth season, should enhance primary production in eutrophic regions of the Canadian Arctic. In contrast, much less change is expected in oligotrophic waters. Confounding these suggestions will be the enhanced vertical mixing associated with a stronger atmosphere–ocean coupling as described above and the opposing buoyancy forces associated with a freshening of the Canada Basin.

Relationship between sea ice cover and phytoplankton chlorophyll a biomass integrated over the euphotic zone for eutrophic (Lancaster Sound, Baffin Bay and Amundsen Gulf hotspot) and oligotrophic (Beaufort Sea, Amundsen Gulf and the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago) regions over 2005–2010. Bars and vertical lines represent average values and standard errors, respectively (Adapted from Ardyna et al. 2011)

2.2 Sea ice and beluga

To investigate the importance of the circumpolar flaw lead for belugas, a historical dataset was analyzed to determine their spring distribution in the eastern Beaufort Sea (Asselin et al. 2011a, b). These data were collected over 1975–1979 by the Canadian Wildlife Service during seal surveys (Stirling et al. 1977; Stirling et al. 1982). The results indicate that belugas select areas with heavy ice concentrations (8/10-10/10) and 200–500 m water depths in spring (Fig. 4, Asselin et al. 2011a, b). During the study period (1975–1979), with the exception of one survey year (1975), landfast ice edges were not selected by belugas in spring (Asselin et al. 2011a, b). The spring distribution of belugas in the eastern Beaufort Sea is hypothesized to result mainly from prey distribution (Asselin et al. 2011a, b), namely arctic cod (Boreogadus saida). This fish is the main prey of belugas in numerous arctic regions (Kleinenberg et al. 1964; Heide-Jørgensen and Teilmann 1994; Dahl et al. 2000) and of eastern Beaufort Sea belugas in summer (Loseto et al. 2009). During the IPY-CFL study, an EK60 echosounder, deployed from the CCGS Amundsen research icebreaker, detected large aggregations of arctic cod during December 2007-April 2008 in the Amundsen Gulf (Geoffroy et al. 2011). Found only in ice-covered waters and at depths greater than 220 m (Geoffroy et al. 2011), the distribution of these aggregations coincides well with the spring beluga distribution in the mid to late 1970s (Asselin et al. 2011a, b). The results of Asselin et al. (2011a, b) further suggested that belugas may use fast ice and coastal regions during springs that are characterized by unusually low ice concentrations, such as during the IPY-CFL project in 2008.

As part of the IPY-CFL project, helicopter surveys identified an aggregation of beluga and bowhead whales at the Franklin Bay ice edge in June 2008 (Asselin et al. 2011b). These whales were engaged in travelling and diving behaviours, and individuals of both species dove repeatedly beneath the ice (Asselin et al. 2011b). Belugas also dive under fast ice in Norton Bay, Alaska, preying on herring and tomcod (Huntington et al. 1999). In the northern Bering Sea, belugas feed at the ice edge and have been observed diving under as a group and re-surfacing in the same place to breathe (Mymrin et al. 1999). The similarities in the under-ice diving behaviour of the belugas observed in Franklin Bay during IPY-CFL and those described by Huntington et al. (1999) and Mymrin et al. (1999), suggest that these animals were feeding under the ice (Asselin et al. 2011a). Springtime under-ice feeding has also been observed for bowheads near Pt. Barrow, Alaska where pelagic prey, copepods and euphausiids were the main target (Carroll et al. 1987). During IPY-CFL, in Franklin Bay during May-June 2008, the large class of zooplankton (>1,000 μm) was mainly composed of the three copepods C. glacialis, Metridia longa and C. hyperboreus with C. hyperboreus contributing the most to biomass (Darnis, unpublished data). In addition, sampling conducted directly below the ice (0–5 m) over 8–21 June 2008 found the highest concentrations of copepods within 1 m of the ice undersurface with C. glacialis having the greatest abundance (Hop et al. 2011). Similarly, Pomerleau et al. (2011) examined the stomach contents of a harvested bowhead from the summer feeding grounds near Shingle Point in the Beaufort Sea and found that it had fed nearly exclusively on the copepod Limnocalanus macrurus as well as Calanus copepods indicating a diet of an estuarine-brackish-water zooplankton community in marine waters strongly influenced by river inputs. Based on these findings by IPY-CFL researchers, Asselin et al. (2011a) concluded that bowheads observed diving under the ice in Franklin Bay were likely engaged in pelagic feeding on copepods.

The findings of the IPY-CFL project support the conclusion of Laidre et al. (2008) that, in comparison with other arctic marine mammals, beluga and bowhead whales are moderately sensitive to climate change, partly due to their lower sensitivity to sea ice changes. While Asselin et al. (2011b) found belugas selected heavy ice cover (8/10-10/10) and water depths of 200–500 m in spring, the results from IPY-CFL in June 2008 confirm that belugas also exploit landfast ice edges (Asselin et al. 2011a). During low ice years, bowhead whales have been found to have improved body condition which may have resulted from an increase in primary productivity (George et al. 2009). In response to a climate change-induced reduction in sea ice concentration and extent, belugas in the eastern Beaufort Sea may concentrate their foraging effort in areas with consistently high densities of prey, such as ice edges. Due to the springtime coupling of phytoplankton and sea ice extent (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2007), the springtime feeding habitat of bowhead whales will likely change but bowheads may thrive in an Arctic with reduced sea ice extent if this does indeed lead to an overall increase in primary productivity.

2.3 Sea ice and polar bears

Sea ice characteristics, including sea ice type and ice concentration, have also been shown to influence habitat selection by polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Polar bears select environments with thick first-year sea ice (FYI) in the spring and summer months, and move in the autumn to MYI (waiting for autumn freeze-up of FYI) or ashore due to the absence of FYI (Stirling et al. 1993, 1999; Ferguson et al. 2000; Durner et al. 2004). Polar bears preferentially select areas with a high ice concentration (Ferguson et al. 2000; Hansen 2004) due to the increased availability and abundance of ringed seals (Phoca hispida). Studies have demonstrated a relationship between changes in sea ice extent or duration, and population estimates or condition of polar bears (Stirling et al. 1999; Regehr et al. 2007; Rode et al. 2007; Durner et al. 2009; Gleason and Rode 2009). The changes in sea ice characteristics described in the literature focus on large-scale variations (i.e., regional or hemispheric scales); however, polar bears have high fidelity to local areas (i.e., subpopulations). Therefore from a habitat perspective, it is critical to examine the variations in sea ice characteristics at smaller spatial and temporal scales. Ice characteristics (i.e., open water, first-year [FYI] and multi-year ice [MYI]) were derived from weekly regional ice charts obtained from the Canadian Ice Service (CIS) over a 31-year period covering 1978–2008, and a regional assessment of sea ice change and variability is provided below for each polar bear management area:

2.3.1 Eastern Canadian Arctic (ECA) cluster

The Eastern Canadian Arctic (ECA) cluster contains approximately one half of the Canadian polar bear population (Aars et al. 2006), and is composed of the Western Hudson Bay (WH), Southern Hudson Bay (SH), Foxe Basin (FB), Davis Strait (DS) and Baffin Bay (BB) subpopulations. For most subpopulation management areas within the ECA cluster, trend analysis suggests an overall increase in open water during both summer and autumn seasons over the 31-year sampling period (Fig. 5). The slopes of the significant trends indicate a 14 % (WH) to a 28 % (DS) per decade increase in summer open water concentration. During autumn, the trends were generally lower for most of the subpopulation management areas, between 6 % (SH) and 24 % (FB) per decade (Fig. 5).

The polar bear subpopulation management areas within this cluster are characterized by low ice concentrations, and thus small anomalies of MYI for both summer and autumn seasons, with no significant trends over the study period (Fig. 6). During summer, the trends in FYI anomalies demonstrated a similar pattern to that of the open water anomalies, with slopes ranging 15–32 % reduction per decade (Fig. 7). This result is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated an earlier sea ice break-up (and thus less FYI) in the WH subpopulation during summer (Stirling et al. 1999; Gagnon and Gough 2005). The summer anomalies were generally positive in the first part of the sampling period for most of the subpopulation areas (Fig. 7). In autumn, the slopes suggested a decrease as well; however, the rate is substantially reduced. The lack of trends would suggest that these anomalies are random and influenced by other factors (e.g., air temperature, Arctic Oscillation).

Changes in polar bear condition and survival within the WH and SH areas correspond to the observed trends in sea ice. The survival and condition of polar bears in the WH subpopulation (Regehr et al. 2007; Stirling et al. 1999) and in the SH subpopulation (Obbard et al. 2006; 2007) were generally higher in the 1980s compared to the late 1990s and 2000s. As described above, these subpopulations experienced a decrease in ice concentration (positive open water anomalies and negative FYI anomalies) in the late 1990s and 2000s, resulting in a decrease in the availability of sea ice and thus reproductive rates as well as recruitment of prey during the summer and autumn seasons (Ferguson et al. 2005; Stirling 2005).

2.3.2 Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA) cluster

The polar bear subpopulation management areas that comprise the CAA cluster include: Gulf of Boothia (GB), Kane Basin (KB), Lancaster Sound (LS), M’Clintock Channel (MC), Norwegian Bay (NW) and Viscount Melville (VM). In both summer and autumn, positive trends in open water anomalies occur in the GB, LS and MC areas over the 31-year study period (Fig. 5). These trends suggest an increase in open water between 13 % per decade and 22 % per decade in the summer, and an increase between 11 % per decade and 30 % per decade in the autumn. Shorter temporal patterns exist in the open water anomalies for the KB, NW and VM areas. In summer, lower open water concentrations (i.e., negative anomalies) generally occur during the first half of the sampling period, after which positive anomalies dominate the pattern (Fig. 5). The timing of this reversal occurs between 1994 and 1995 for the NW and VM areas in both summer and autumn. For KB, the timing of this reversal in anomalies is later in the decade.

The slope of the trends suggests a relatively large decrease in MYI within the GB and MC areas, approximately 20 % per decade for MC in both seasons and 40 % per decade for GB in both seasons (Fig. 6). On a shorter time-scale, large negative anomalies tend to dominate the KB, LS, NW and VM areas in the mid- to late 1980s, as well as in the late 1990s and early 2000s for both seasons. Another interesting result is that these areas exhibit large interannual variability in the MYI anomalies, with deviations from the 31-year average in excess of 20 %.

A positive trend in summer FYI anomalies is evident for the GB area, suggesting an overall increase of approximately 8 % per decade over the 31-year study period (Fig. 7). Opposite trends in FYI anomalies are estimated for the KB area (Fig. 7). A possible explanation for this difference is that due to a trend towards less FYI in both the BB and DS areas (located to the south of the KB area), more FYI may be moving from the KB area and melting further south. For the other subpopulation management areas, positive anomalies dominate during the early and mid-1980s, followed by negative anomalies during the late-1980s to mid-1990s and again a predominance of positive anomalies during the second part of the study period (Fig. 7).

2.3.3 Beaufort Sea (BS) cluster

The Beaufort Sea (BS) cluster is composed of the Southern Beaufort (SB) and Northern Beaufort (NB) subpopulation management areas. These areas do not exhibit a temporal trend in the summer open water anomalies (Fig. 5). A statistically significant trend in autumn open water anomalies is only evident for the SB area, with a 27 % per decade increase over the sampling period (Fig. 5). The open water anomalies exhibit large interannual variability, with anomalies greater than 20 % occurring frequently throughout the sampling period.

Over the 31-year study period, summer FYI decreased by 20 % per decade for the NB area and 11 % per decade for the SB area. Temporal patterns over short time scales are evident for this cluster. During autumn season, the FYI anomalies are generally positive during the early to mid-1980s, followed by negative anomalies until the mid- or late 1990s, and concluding with both positive and negative anomalies (Fig. 6).

Over the 31-year study period, summer FYI decreased by 20 % per decade for the NB area and 11 % per decade for the SB area. Temporal patterns over short time scales are evident for this cluster. During autumn, the FYI anomalies are generally positive during the early to mid-1980s, followed by negative anomalies from the late 1980s to mid- or late 1990s, and concluding with generally negative anomalies (Fig. 7). The FYI anomalies, along with the trends in the open water anomalies, correspond to a reduction in survival and breeding of polar bears and cub of the year (COY) litter survival in the SB subpopulation during the 2000s as reported by Regehr et al. (2007, 2010). Polar bear population estimates within the SB subpopulation management area increased from the mid-1980s into the 1990s and then decreased in the 2000s (Amstrup et al. 1986; Regehr et al. 2006; Hunter et al. 2007; Rode et al. 2007). During this period, anomaly trends indicate that open water was diminished while FYI coverage was more predominant during the mid-1980s to mid-1990s, compared to the 31-year average, resulting in greater access to prey.

Recent past and future variability in the geophysical and thermodynamic state of sea ice will influence polar bear habitat in both the short and longer term. In the short term less sea ice (both multi-year and first-year) will result in greater sea ice dynamics and thus greater ridging and rough ice in certain subpopulation regions. This can create favourable ringed seal and thus polar bear habitat. Over the longer term, the trend towards increasing duration of open water for a number of the subpopulations within Canada (especially along the southern edge of sea ice extent) will result in a reduction in polar bear habitat and may ultimately result in permanent negative consequences on polar bear population health (Stirling et al. 1999; Regehr et al. 2007).

3 Sea ice and climate-relevant gas exchange

One of the other major consequences of a changing icescape (Barber et al. 2012; this issue) is in the effect this has on the exchange of climatically relevant gases (e.g., CO2) across the ocean-sea-ice-atmosphere interface. The CO2 absorbed by the global marine system presently offsets about 30 % of present anthropogenic emissions (Denman et al. 2007), but the factors that control air-sea CO2 exchange are still largely unknown. Regionally, the ocean’s CO2 uptake varies widely from source to sink, both seasonally and spatially across the globe (Takahashi et al. 2009). Large gaps still exist in our understanding of the mechanisms causing the observed variability (in space and time), particularly in regions with sparse data coverage, such as the Arctic.

Gas exchange variability is largely due to the processes affecting both the partial pressure of CO2 at the seawater’s surface (pCO2), and the gas transfer velocity. They are related to the CO2 flux (F) through the bulk formulation:

where α is the solubility of CO2 in seawater: and k is the gas transfer velocity, which controls the rate at which the exchange can occur; and ΔpCO2 is the air-sea difference in CO2 partial pressures:

with subscripts sw and a representing the surface sea water and air, respectively. While the formulation in Eq. 1 has significant limitations (mainly resulting from definitions of k, e.g., Wanninkhof et al. (2009)), it has proven useful in studies of air-sea gas exchange over open water. In the presence of sea ice, however, this traditional approach to understanding gas fluxes fails because of 1) exchanges that occur between the air and the ice; and 2) hydrodynamic processes associated with ice edges that are not accounted for in experimental measurements of k in open waters.

A recent review of global air-sea pCO2 differences (Chen and Borges 2009) has reinforced the paradigm that the waters of high-latitude continental shelves are generally undersaturated in CO2, relative to the atmosphere, and therefore act as CO2 sinks. Some of the highest CO2 undersaturations reported anywhere in the oceans have been observed in the high latitudes (Takahashi et al. 2009), and because continental shelves constitute over 50 % of the surface area of the Arctic Ocean (Jakobsson et al. 2004), it is tempting to assume that the Arctic Ocean and its peripheral seas are annually strong net sinks of atmospheric CO2. However, we lack insight into important processes associated with sea ice that may or may not affect the uptake of CO2 and, as a consequence, the role of the Arctic Ocean in the global carbon budget is not well constrained.

In addition to uncertainties in direct air-ice CO2 exchanges (e.g., Semiletov et al. 2004; Zemmelink et al. 2006; Delille et al. 2007; Nomura et al. 2010; Papakyriakou and Miller 2011; Miller et al. 2011b), the factors affecting pCO2sw and k across the air-sea interface in sea–ice-dominated waters appear to differ from those processes in ice-free environments (Loose et al. 2009). Gas transfer velocities (k) are likely enhanced by greater boundary-layer turbulence and modified by fetch limitations in the presence of sea ice (Else et al. 2011). Also, sea ice may increase under-ice pCO2sw through rejection of dissolved inorganic carbon with salt during sea ice formation and growth (Miller et al. 2011a,b; Rysgaard et al. 2007), with the introduction of melt water over the summer season effectively decreasing pCO2sw (Chierici et al. 2011; Else et al. 2012; Shadwick et al. 2011; Rysgaard et al. 2009).

Particularly important questions remain about the significance of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) precipitation and dissolution in sea ice on the underwater CO2 system and air-sea CO2 exchange. During CaCO3 formation, CO2 is released to the aqueous phase, raising pCO2 and decreasing the ratio of total alkalinity to total inorganic carbon (TA:TIC) within ice brines. If that high-TIC brine drains from the ice, the ultimate melt water from that ice will have a high TA:TIC ratio, increasing the buffering capacity, and ability to absorb atmospheric CO2, of the summer surface waters. In addition, CaCO3 will consume CO2 on dissolution, further lowering the pCO2 of surface seawater (Delille et al. 2007; Rysgaard et al. 2007). Several authors have indicated that CaCO3 should be the first salt to precipitate from sea ice brine at temperatures as high as −2.2°C [Thomas and Nelson 1956; Assur 1960], however the occurrence of CaCO3 (as ikaite) in natural sea ice has only recently been confirmed (Dieckmann et al. 2008). The processes surrounding its precipitation and dissolution in sea ice could be an important component of the global marine carbon budget (Rysgaard et al. 2011), although questions remain about the conditions necessary for CaCO3 formation within sea ice (Thomas et al. 2010 and references within).

While the research to date has been instrumental in raising awareness of the likely significance of sea ice in the marine carbon budget (see also Rysgaard et al. 2011), the potential effects of sea ice on direct air-sea CO2 transfer have received little consideration in global carbon budgeting and modelling exercises. The IPY-CFL Study provided a unique opportunity for researchers to document the CO2 dynamics of an arctic polynya/flaw lead system over an annual cycle, and hence provided the opportunity to address many of the knowledge gaps outlined above. In particular, we gained a better understanding of the seasonally varying factors that affect the sea ice carbonate system, its linkages with the inorganic carbon dynamics of near-surface seawater, and the air-sea CO2 exchange in ice-dominated waters.

Our measurements covered the full annual cycle of sea ice formation and decay, ranging from young, actively growing frazil and nilas to first-year sea ice in advanced stages of melt. Initial ice consolidation occurred by the middle of October, and by early November much of the region was ice-covered (Else et al. 2011). The sea ice remained mobile throughout the winter, creating numerous ice openings and thus allowing for widespread and rapid ice formation (Else et al. 2011). The region’s sea ice was dominated by thick (130–160 cm), slowly growing first-year ice between March and May, after which melt began (Geilfus et al. 2012). Mobile ‘drift’ ice was sampled in April, while ice sampled in May and June was largely landfast (Geilfus et al. 2012). By June, less than 10 % of the region was ice-covered, and the region was nearly ice-free by the first week in July (Else et al. 2012).

3.1 Sea ice and the carbonate system

Throughout our study, total dissolved inorganic carbon (TIC) in brine was observed to generally covary with sea ice salinity (Miller et al. 2011a; Geilfus et al. 2012) up to salinities greater than 100 PSU. A strong relationship between air temperature (AT) and salinity was also observed in the brines (Geilfus et al. 2012) for all but the youngest sea ice types at very high salinities (Miller et al. 2011a). Collectively, many of our observations (Geilfus et al. 2012; Miller et al. 2011a) support the hypothesis (attributed to Rysgaard et al. 2007) that CaCO3 precipitation within sea ice can preferentially retain alkalinity in the ice relative to TIC (Fig. 8). We can confidently state that the formation of sea ice transports TIC out of the surface waters (i.e., the top meter or two) into the atmosphere and into the underlying seawater; however, the extent to which TIC is transported below the polar mixed layer is yet to be determined.

The alkalinity-to-dissolved inorganic carbon (TA:TIC) (values normalized to a salinity of 35 PSU) relationship in brine, seawater and sea ice samples (Adapted from Geilfus et al. 2012)

3.2 Surface seawater CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) and air-sea-ice flux

The pCO2 within the sea ice was highly variable, even at the same depth in close horizontal proximity (Geilfus et al. 2012; Miller et al. 2011a). The range of sea ice pCO2 observed during IPY-CFL was far in excess of observations for sea ice surrounding Antarctica, which are limited to only spring and late winter studies (Geilfus et al. 2012; Delille et al. 2007). At freeze-up, pCO2 was high and in excess of the atmospheric value in nearly all of the young ice types sampled (Miller et al. 2011a). In general, pCO2 was observed to co-vary with temperature (Geilfus et al. 2012; Miller et al. 2011a), with the highest values (over 13 times atmospheric levels) being found in the coldest sea ice (Fig. 9). The concomitant decrease in brine solubility with increasing salinity on cooling, as well as possible CaCO3 precipitation, gives rise to high sea ice pCO2 during the cold season. In the late spring and summer, pCO2 (and CT) dropped rapidly in response to a combination of processes that included: brine dilution from sea ice melt, CaCO3 dissolution, and CO2 uptake by sea ice algae. The sea ice algae contributed to a reduction in sea ice pCO2 and TIC early in the melt process (Shadwick et al. 2011), although the dominant factor lowering pCO2 in the ice brines was dilution by melt (Geilfus et al. 2012). By June, brine was highly undersaturated (relative to atmospheric levels), and at times, the brine was almost completely depleted of CO2 (Geilfus et al. 2012).

Left: The relationship between pCO2 and sea ice temperature resulting from data collected at sampling stations (various symbols). The grey line shows the expected effect on brine pCO2 associated with dilution alone. (Adapted from Geilfus et al. 2012)

The direction and magnitude of the air-surface flux appeared to be determined by the stage of ice development and temperature. Large air-sea gradients in pCO2 were observed from November to May and diminished in June (Shadwick et al. 2011; Else et al. 2012). Ship-based eddy covariance measurements of the air-sea CO2 flux were large in areas of open water that supported rapid frazil growth in the fall and winter (Else et al. 2011). The flux direction was dictated by the prevailing air-sea (or air-sea-ice) pCO2 gradient (Miller et al. 2011a), and exchange rates were found to be several factors larger than would be predicted using standard parameterizations of the gas transfer velocity (Eq. 1). We hypothesized that high water-side turbulence associated with rapid surface heat loss was the major cause of the enhanced gas exchange. A calculation of the potential CO2 uptake over the fall and winter showed that winter gas exchange through leads and openings in the sea ice may be at least as important as during the open-water months (Else et al. 2011).

Gas exchange was also observed over sea ice, albeit at much lower rates than reported by Else et al. (2011) for open water. Miller et al. (2011a) indicate that excess pCO2 in newly consolidated and relatively warm ice favoured CO2 release to the atmosphere. The authors speculated that the efflux would dramatically drop with surface cooling beyond about −9°C. Geilfus et al. (2012) confirmed that fluxes were rarely observed when the ice surface temperature was below −10°C. The CO2 efflux from sea ice increased over a temperature range between −10°C and −6°C, with the process reversing to a CO2 uptake over the temperature range between −6°C to 0°C. Maximum rates of efflux and uptake were respectively 0.84 mmol m−2 day−1 and −2.6 mmol m−2 day−1. Collectively, these studies (Miller et al. 2011a; Geilfus et al. 2012) showed that the CO2 flux was controlled by ice temperature, likely through its control on brine volume and permeability, and the brine-atmosphere pCO2 concentration gradients. The direction of CO2 release (up to the atmosphere or down into the underlying water) by the sea ice depended on the permeability of the ice (Miller et al. 2011a).

3.3 Sea ice and ocean carbon transport

Sea ice cover is associated with a well-developed polar mixed layer in the upper 50 m of the water column (Shadwick et al. 2011). Large seasonal variability in CO2 system parameters was observed in the top 20 to 40 m under the sea ice (Chierici et al. 2011). The seasonal cycle of TA and TIC was closely coupled with trends in salinity (Fig. 10). High under-ice salinity was observed in April and May and extended throughout the polar mixed layer. The pulse of salinity was the result of brine rejected during sea ice formation, and the resulting convection and mixing act to elevate both under-ice TA and TIC (Chierici et al. 2011; Shadwick et al. 2011).

As expected, the contribution of sea ice melt had a strong seasonal cycle, ranging from a minimum in March and April, increasing in June and reaching a maximum in September (Chierici et al. 2011; Shadwick et al. 2011). However, even in spring, before the ice cover cleared, under-ice water pCO2 decreased to below atmospheric levels due to melt-water input (Geilfus et al. 2012; Chierici et al. 2011).

Through the IPY-CFL project, researchers were able to track, for the first time, inorganic carbon stores and transport within and between seasonal sea ice, under-ice seawater and the near-surface atmosphere over an annual cycle of sea ice growth and decay. The data revealed important relationships among components of the carbonate system (TA, pCO2, TIC) and sea ice geophysical (salinity, permeability) and thermodynamic (temperature) properties that clarify ideas about the sea ice CO2 system developed from previous short-term field studies (e.g., Miller et al. 2011b; Rysgaard et al. 2007; Delille et al. 2007). Although the relationships reported here constitute an important step towards parameterizing sea ice carbon system properties, further work is needed to determine how geographically representative our results are.

Our measurements of enhanced CO2 exchange in a polynya/flaw lead system throughout the winter season are important because they require us to rethink the role of the wintertime polar oceans in the global carbon cycle and budget. Perhaps most importantly, our study confirmed that carbon is injected into the under-ice water along with brine drainage from actively growing sea ice, which together with evidence of CaCO3 precipitation in sea ice, supports the assertion that sea ice could likely be a key component of the global solubility pump. Yet to be determined is what proportion of the brine will sink below the surface mixed layer, allowing the carbon that is contained in the brine to be sequestered away from the atmosphere.

A thinner more mobile sea ice pack will result in more annual sea ice growth and open water (leads and polynyas) during the winter season. If an increase in the amount of seasonal sea ice formed each year is associated with a rise in shelf and deep water formation, then pCO2 and TIC drainage with brine transport could provide a negative feedback in climate-associated changes in the global carbon cycle.

4 Sea ice and contaminants

Polar regions, and in particular sea icescapes, are particularly susceptible to the effects of chemical contaminants (Macdonald et al. 2005). Contaminants from the lower latitudes are transported through ocean and atmospheric currents into the Arctic (Macdonald et al. 2000), where they become available for uptake in biota (Mackay and Fraser 2000). Some contaminants biomagnify in the arctic food web (Macdonald et al. 2000) leading to greater health concerns as a large part of the traditional diet for Northern peoples is marine mammals. Specifically of concern is the neurotoxic species methyl mercury, where daily intake values can exceed the tolerable levels set by the World Health Organization (Van Oostdam et al. 2005; Hylander and Goodsite 2006).

During IPY, several studies took place that looked at linkages between the sea ice and contaminant transport. Pućko et al. (2010a, b, 2011a, b) conducted a series of studies on hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) during IPY-CFL. HCHs, among the most abundant organochlorine pesticides in the Arctic (Li and Macdonald 2005), were released to the environment between the 1950s and 2000 in two main formulations: technical HCH (α isomer 60–70 %, β isomer 5–12 %, γ isomer 10–15 %) and lindane (pure γ isomer). α-HCH is the only chiral HCH isomer, consisting of two mirror-image enantiomers referred to as (+) and (−). Enantiomer fraction \( \left( {{\text{EF}} = \left( + \right)\alpha - {\text{HCH}}/\left( {\left( + \right)\alpha - {\text{HCH}} + \left( - \right)\alpha - {\text{HCH}}} \right)} \right)\) differing from 0.5 indicates biological degradation (Harner et al. 2000). General relationships between HCH concentrations and sea ice physical and thermodynamic characteristics were presented in Pućko et al. (2010a). They determined, through the use of sump-holes in sea ice, that 50 % of the total HCH in ice could be entrapped in the crystal matrix. Levels of HCHs in the brine exceeded the under-ice water concentrations by a factor of three, suggesting that the brine ecosystem has been, and continues to be, highly exposed to HCHs. In another study, Pućko et al. (2010b) found evidence that both geophysics and thermodynamics of ice were important for understanding pathways of accumulation or rejection of HCHs. Both α- and γ-HCH concentrations as well as α-HCH enantiomer fractions were measured in various ice classes and ages from the Canadian High Arctic. In general, α-HCH concentrations and vertical distributions were highly dependent on the initial entrapment of brine and the subsequent desalination process. In contrast, γ-HCH levels and distribution in sea ice were not as clearly related to ice formation processes. Further, the same authors described how the complexity of physical interactions between different abiotic compartments in the arctic marine environment provides for equal complexity in HCH pathways (Pućko et al. 2011a). Finally, moving to a broader perspective, HCH elimination pathways and timescales in the Canadian sector of the Arctic Ocean were discussed in detail with particular emphasis on the role of ice formation in vertical redistribution of HCHs in the upper layer of the Arctic Ocean in a solvent-depleting manner (Pućko et al. 2011b).

Wong et al. (2011) looked at the influence of sea ice cover on the air-water exchange of organohalogen compounds in the Canadian Arctic. They found that the fugacity gradient of α-HCH in the Beaufort Sea was greater during ice-covered winter conditions than at the beginning of the spring ice break-up. This meant that the loss of sea ice facilitates α-HCH evasion from the Arctic Ocean into the boundary layer, raising atmospheric concentrations.

A research program investigating the movement of chemicals between the Ocean, Atmosphere, Sea Ice and Snow pack (‘OASIS-Canada’) looked at the ozone (O3) and mercury (Hg) atmospheric depletion events over the Arctic Ocean during IPY-CFL. The project aimed to better understand how and why, during the first sunrise of the arctic spring, the potent greenhouse gas ozone and the toxic chemical mercury disappear from the air near the ground along the coast of the frozen ocean. The OASIS and IPY-CFL projects were the first to record extensive measurements of mercury and ozone over the frozen oceans (Nghiem et al. 2012). The large scale of ozone and mercury depletion events over the Arctic Ocean was confirmed. Depletion episodes in the spring were observed everywhere: they were severe and often lasted for several days to weeks. Direct ozone loss to frozen surfaces was usually slow. Mercury was found to deplete and emit around the snow pack and there were indications that these processes may be different over frost-flower-covered ice. During some studies it was observed that the disappearances only occurred when the air temperature was below ~ −20°C. During the OASIS-09 study near Barrow Alaska, further data were obtained examining the exchange between the surface and air. For the first time it was clearly recorded that after deposition less mercury is re-emitted from the frozen ocean to the atmosphere than from the inland snowpack, showing that different processes govern the retention of mercury deposited over the Arctic Ocean.

In another mercury study within the IPY-CFL project, Chaulk et al. (2011) reported on the distribution and transport of mercury across the ocean-sea-ice-atmosphere interface in the southern Beaufort Sea. Despite being sampled at different sites under various atmospheric and snow cover conditions, mercury concentrations from first-year ice were generally low and varied within a remarkably narrow range. All the first-year ice cores, however, showed significant mercury enrichment in the surface granular ice layer. By measuring Hg concentrations in thin, new ice formed during the mercury depletion event and by profiling Hg distribution in snow and ice cores, Chaulk et al. (2011) showed that mercury depletion events appeared not to be an important factor in determining Hg concentrations in sea ice except for frost flowers and in the melt season when snowpack Hg leaches into the sea ice. Instead, they suggested that the surface enrichment of Hg in the first-year ice was primarily due to brine pocket concentration and particle enrichment in the granular ice. Of particular significance is their finding that mercury concentration in sea ice brine could be as high as 70 ng L−1 (which is about 350 times the level of mercury in surface seawater) and changes as the season progresses. As brine is the primary habitat for microbial communities responsible for sustaining the food web in the Arctic Ocean, the high and seasonally changing Hg concentrations in brine and its potential transformation may have a major impact on Hg uptake and exposure in arctic marine ecosystems under a changing climate (Chaulk et al. 2011).

Ahrens et al. (2011) looked at perfluoroalkyl compounds (PFCs) in the Canadian arctic atmosphere during IPY. Data were collected in Hudson Bay, the Labrador Sea and the Beaufort Sea. They looked at the spatial distribution of four different classes of PFCs: perfluoroalkyl carboxylates (PFCAs), fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs), fluorinated sulfonamides (FOSAs), and sulfonamidoethanols (FOSEs). FTOHs had the greatest concentrations in the gas phase, while the FOSEs were dominant in the particle phase. They found that the general trend for the particle-associated fraction concentrations was PFCAs > FOSEs > FOSAs > FTOHs. They concluded that the air temperatures influenced the atmospheric partitioning behaviour of these compounds, and that the atmospheric behaviour was influenced by temperature-driven exchange with the surface, including areas of snow-covered sea ice and open water.

Climate change will have a direct impact on organisms’ susceptibility to contaminant exposure, or an indirect impact on contaminant exposure through its effects on ecosystems (Schiedek et al. 2007). In the case of direct impacts, contaminant exposure interacts with direct and indirect stresses on ecosystems and biota, thus altering contaminant bioavailability, toxicity or biological effects. In the case of indirect impacts, change in environmental conditions and pathways will alter the transport, transfer, deposition and fate of contaminants, thus affecting biological exposure. Contaminant research conducted during IPY not only advanced current understanding of contaminant pathways in the arctic cryosphere but also addressed the question of how the processes may change as a result of anthropogenically-forced warming and associated sea ice loss, emphasizing in particular the indirect impacts on contaminant exposures. Work by Wong et al. (2011), Pućko et al. (2010a, b, 2011a, b) and Ahrens et al. (2011) indicated that sea ice plays a crucial role in the distribution and transport of organic contaminants in the Arctic. Similarly, studies examining mercury pointed to the importance of sea ice and snow for the air-snow-ice-ocean transfer (Chaulk et al. 2011; Nghiem et al. 2012). In light of IPY-CFL research, it is evident that atmosphere-snow-ice-ocean coupling is crucial for contaminant exposures in the Arctic Ocean, and thus any human-induced shifts within the natural system will likely have profound and directional consequences for contaminant transport, wet and dry deposition, gas exchange and distribution.

5 Conclusions

The research results stemming from the Canadian IPY program described the breadth and depth of the ‘consequences’ of sea ice change and coupling between the sea icescape and the biophysical and chemical processes which depend on the icescape. The results within this paper can be used in the assessment of the consequences of climate change on the integrated ecological components of the arctic marine system, directly attributable to a changing sea ice environment.

This paper has outlined a number of key consequences of climate change in the Arctic that will affect all levels of the arctic ecosystem, and subsequently northern communities and socioeconomic activities. A summary of key results is as follows: 1) A decreasing ice cover, and consequently a longer growth season, should enhance primary production in eutrophic regions of the Canadian Arctic. An increase should also be expected in oligotrophic waters however, to a much lesser extent. Conditions associated with climate change can increase atmosphere–ocean forcing resulting in upwelling of nutrient-rich waters from a Pacific Ocean origin to replace nutrient-replete surface waters along the arctic coastline and its ice edge zones, thereby enhancing local primary productivity and associated food webs. The strength and efficiency of this upwelling will depend on where fast ice edges form relative to bathymetry and the prevalence of upwelling-favourable winds relative to the orientation of the fast ice edges. 2) Both sea ice thermodynamic and dynamic processes affect ringed seal/polar bear habitats and the complex relationship between their habitat and climate change. The timing of fast ice formation and the role this plays in ridge and rubble zone formation was seen as a key habitat driver using both traditional and western science knowledge. Similarly the length of the open water season is very important to the foraging success of polar bears. This open water duration is now at a maximum in the southern Hudson Bay range and is a concern in many other polar bear habitat management districts. The reduction in multi-year sea ice and its replacement by first-year ice types may temporarily improve polar bear habitat as bears do not typically hunt in multi-year sea ice. 3) The ice edges bordering open waters of flaw leads are areas of high biological production and are also observed to be important beluga habitat. Upwelling at these ice edges can provide event driven pulses of productivity early in the spring season and the timing of these upwellings may occur earlier in a warmer climate. 4) Delayed freeze-up, early ice break-up and increased winter ice motion will promote more opportunities for air-sea gas exchange in the Arctic. Since most regions of the Arctic are potential sinks for CO2, the likely result of this will be an increase in the ability of the Arctic Ocean to absorb atmospheric CO2. The reduction of multi-year ice extent and concomitant increase in first-year ice will also likely play a role in enhancing the sea ice processes (i.e., CaCO3 formation, TIC/TA partitioning and brine drainage) that appear to be important in sequestering atmospheric CO2 in the ocean. 5) Contaminants are ubiquitous throughout the Arctic and sea ice plays a very important role in the sources, sinks and pathways of these contaminants. Significant impacts are related to the brine chemistry of sea ice and this is important because in a warmer Arctic we will expect to find more (and a longer duration) of young ice types including nilas, frost flowers and new ice. Several projects confirmed that severe mercury and ozone depletion events were occurring over the Arctic with the return of the sun at the end of the polar winter. This is a significant geochemical process that has potential implications for food security and the health of northern peoples.

References

Aars J, Lunn NJ, Derocher AE (2006) Polar bears. Occasional paper 32. Proceedings of the 14th Working Meeting of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, June 20–24 2005, Seattle, Washington, USA

ACIA (Arctic Climate Impact Assessment) (2005) Arctic climate impact assessment: scientific report. University of Cambridge Press, Cambridge

Ahrens A, Shoeib M, Del Vinto S, Codling G, Halsall C (2011) Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the Canadian Arctic atmosphere. Environ Chem 8(4):399–406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/EN10131

Amstrup SC, Stirling I, Lentfer JW (1986) Past and present status of polar bears in Alaska. Wildlife Soc B 14:241–254

Ardyna M, Gosselin M, Michel C, Poulin M, Tremblay J-É (2011; in press) Environmental forcing of phytoplankton community structure and function in the Canadian High Arctic: contrasting oligotrophic and eutrophic regions. Mar Ecol Prog Ser

Arrigo KR, van Dijken G, Pabi S (2008) Impact of a shrinking Arctic ice cover on marine primary production. Geophys Res Lett 35(19):L19603. doi:10.1029/2008gl035028

Asselin NC, Barber DG, Stirling I, Ferguson SH, Richard PR (2011a) Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) habitat selection in the eastern Beaufort Sea in spring, 1975 to 1979. Polar Biol. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-0990-5

Asselin NC, Barber DG, Richard PR, Ferguson SH (2011b; In press) Occurrence, distribution and behaviour of beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) whales at the Franklin Bay ice edge in June (2008). Arctic

Assur, A. (1960) Composition of sea ice and its tensile strength. Res Rep 44:49, U.S. Army Snow Ice and Permafrost Res. Establ., Wilmettee, III

Barber DG, Galley R, Asplin MG, De Abreau R, Warner KA et al (2009) Perennial pack ice in the southern Beaufort Sea was not as it appeared in the summer of 2009. Geophys Res Lett 36:L24501. doi:10.1029/2009GL041434

Barber DG, Asplin M, Gratton Y, Lukovich J, Galley R et al (2010) The International Polar Year (IPY) Circumpolar Flaw Lead (CFL) system study: introduction and physical system. Atmos- Ocean 48(4):225–243. doi:3137/OC317.2010

Barber DG, Asplin MG, Raddatz R, Candlish L, Nickels S et al (2012; this issue) Causes of change and variability in sea ice during the 2007–2008 Canadian International Polar Year program. Clim Change

Carroll GM, George JC, Lowry LF, Coyle KO (1987) Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) feeding near Point-Barrow, Alaska, during the 1985 spring migration. Arctic 40(2):105–110

Chaulk A, Stern G, Armstrong D, Barber D, Wang F (2011) Mercury distribution and transport across the ocean-sea ice-atmosphere interface in the Arctic Ocean. Environ Sci Technol 45(5):1866–1872

Chen D-TA, Borges AV (2009) Reconciling opposing views on carbon cycling in the coastal ocean: continental shelves as sinks and near-shore ecosystems as sources of atmospheric CO2. Deep Sea Res Part II 33:L12603. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.01.001

Chierici M, Fransson A, Lansard B, Miller LA, Mucci A et al (2011) The impact of biogeochemical processes and environmental factors on the calcium carbonate saturation state in the Circumpolar Flaw Lead in Amundsen Gulf, Arctic Ocean. J Geophys Res 116:C00G09. doi:10.1029/2011JC007184

Dahl TM, Lydersen C, Kovacs KM, Falk-Petersen S, Sargent J et al (2000) Fatty acid composition of the blubber in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas). Polar Biol 23(6):401–409

Darnis G, Robert D, Pomerleau C, Link J, Archambault P et al (2012) Current state and changing trends in Canadian Arctic marine ecosystems: II. Secondary production and biodiversity. Clim Change

Delille B, Jourdain B, Borges AV, Tison J-L, Delille D (2007) Biogas (CO2, O2, dimethylsulfide) dynamics in spring Antarctic fast ice. Limnol Oceanogr 52:1367–1379

Denman K, Brasseur G, Chidthaisong A, Ciais P, Cox PM et al (2007) Couplings between changes in the climate system and biogeochemisty. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M et al (eds) Climate Change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Chapter 7. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

Dieckmann GS, Nehrke G, Papadimitriou S, Göttlicher J, Steininger R et al (2008) Calcium carbonate as ikaite crystals in Antarctic sea ice. Geophys Res Lett 35:L08501. doi:10.1029/2008GL033540

Dmitrenko I, Tyshko K, Kirillov S, Eicken H, Holemann J, Kassens H (2005) Impact of flaw polynyas on the hydrography of the Laptev Sea. Global Planet Change 48:9–27

Dunbar MJ (1981) Physical causes and biological significance of polynyas and other open water in sea ice. In: Stirling I, Cleator HJ (eds) Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic., vol 45. Canadian Wildlife Service Occasionnal Paper, pp 29–43

Durner GM, Amstrup SC, Nielson R, McDonald TL (2004) Using discrete choice modeling to generate resource selection functions for female polar bears in the Beaufort Sea. In: Huzurbazar S (ed) Resource selection methods and applications, Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Resource Selection Modeling. January 2003, Laramie, Wyoming, pp 107–120

Durner GM, Douglas DC, Nielson RM, Amstrup SC, McDonald TL et al (2009) Predicting 21st-century polar bear habitat distribution from global climate models. Ecol Monogr 79:25–58. doi:10.1890/07-2089.1

Else BGT, Papakyriakou TN, Galley RJ, Drennan WM, Miller LA et al (2011) Wintertime CO2 fluxes in an Arctic polynya using eddy covariance: evidence for enhanced air-sea gas transfer during ice formation. J Geophys Res 116:C00G03. doi:10.1029/2010JC006760

Else BGT, Papakyriakou TN, Galley RJ, Mucci A, Gosselin et al (2012) Annual cycles of pCO2sw in the southeastern Beaufort Sea: New understandings of air-sea CO2 exchange in Arctic polynyas. Submitted to J Geophys Res 117:C00G13, doi:10.1029/2011JC007346

Ferguson SH, Taylor M, Messier F (2000) Influence of sea ice dynamics on habitat selection by polar bears. Ecology 81:761–772. doi:10.1890/0012-9658

Ferguson SH, Stirling I, McLoughlin P (2005) Climate change and ringed seal (Phoca hispida) recruitment in western Hudson Bay. Mar Mammal Sci 21(1):121–135

Forest A, Tremblay J-É, Gratton Y, Martin J, Gagnon J, Darnis G et al (2011) Biogenic carbon flows through the planktonic food web of the Amundsen Gulf (Arctic Ocean): a synthesis of field measurements and inverse modeling analyses. Prog Oceanogr 91:410–436. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2011.05.002

Gagnon AB, Gough WA (2005) Trend and variability in the dates of ice freeze-up and break-up over Hudson Bay and James Bay. Arctic 58:370–382

Geilfus N-X, Carnat G, Papakyriakou T, Tison J-L, Else B et al (2012) pCO2 dynamics and related air-ice CO2 fluxes in the Arctic coastal zone (Amundsen Gulf, Beaufort Sea). J Geophys Res 117:C00G10. doi:10.1029/2011JC007118

George JC, Nicolson C, Drobot S, Maslanik J, Rosa C (2009) Update on SC/57/E13: Progress Report: Sea ice density and bowhead whale body condition (unpublished). International Whaling Commission,

Geoffroy M, Robert D, Darnis G, Fortier L (2011) The aggregation of polar cod in the deep Atlantic layer of ice-covered Amundsen Gulf (Beaufort Sea) in winter. Polar Biol 1–13. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-1019-9

Gleason JS, Rode KD (2009) Polar bear distribution and habitat association reflect long-term changes in Fall Sea ice conditions in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea. Arctic 62:405–417

Hansen DJ (2004) Observations of habitat use by polar bears, Ursus maritimus, in the Alaskan Beaufort, Chukchi and northern Bering Seas. Can Field Nat 118(3):395–399

Harner T, Wiberg K, Norstrom R (2000) Enantiomer fractions are preferred to enantiomer ratios for describing chiral signatures in environmental analysis. Environ Sci Technol 34:218–220

Heide-Jørgensen MP, Teilmann J (1994) Growth, reproduction, age structure and feeding habits of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in West Greenland waters. Meddelelser om Gronland Biosci 39:195–212

Heide-Jørgensen MP, Laidre KL, Logsdon ML, Nielsen TG (2007) Springtime coupling between chlorophyll a, sea ice and sea surface temperature in Disko Bay, West Greenland. Prog Oceanogr 73(1):79–95. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2007.01.006

Hop H, Mundy CJ, Gosselin M, Rossnagel AL, Barber DG (2011) Zooplankton boom and ice amphipod bust below melting sea ice in the Amundsen Gulf, Arctic Canada. Polar Biol. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-0991-4

Hunter CM, Caswell H, Runge MC, Regehr EV, Amstrup SC et al (2007) Polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea III: Demography and population growth in relation to sea ice conditions. USGS Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Administrative Report

Huntington HP, Community of Buckland, Community of Elim, Community of Koyuk, Community of Point Lay, Community of Shaktoolik (1999) Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the Eastern Chukchi and northern Bering Seas, Alaska. Arctic 52(1):49–61

Hylander L, Goodsite M (2006) Environmental costs of mercury pollution. Sci Total Environ 368:352–370

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007) Climate change 2007: the scientific basis. Contribution of working group I to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jakobsson M, Grantz A, Kristoffersen Y, MacNab R (2004) The Arctic Ocean: boundary conditions and background information. In: The organic carbon cycle in the Arctic Ocean. Springer, New York, p 363

Kleinenberg SE, Yablokov AV, Bel’kovich BM, Tarasevich MN (1964) Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) investigation of the species (trans: Translations IPfS). Jerusalem

Kwok R (2008) Summer sea ice motion from the 18 GHz channel of AMSR-E and the exchange of sea ice between the Pacific and Atlantic sectors. Geophys Res Lett 35:L03504. doi:10.1029/2007GL032692

Laidre KL, Stirling I, Lowry LF, Wiig O, Heide-Jorgensen MP et al (2008) Quantifying the sensitivity of arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecol Appl 18(2):S97–S125

Li Y-F, Macdonald RW (2005) Sources and pathways of selected organochlorine pesticides to the Arctic and the effect of pathway divergence on HCH trends in biota: a review. Sci Total Environ 342:87–106

Link H, Archambault P, Tamelander T, Renaud PE, Piepenburg D (2011) Regional Variability and Spring-to-Summer Changes of Benthic Processes in the Western Canadian Arctic. Polar Biol. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-1046-6

Liu JP, Curry JA, Hu YY (2004) Recent Arctic sea ice variability: connections to the arctic oscillation and the ENSO. Geophys Res Lett 31:L09211. doi:10.1029/2004GL019858

Loose B, McGillis WR, Schlosser P, Perovich D, Takahashi T (2009) Effects of freezing, growth, and ice cover on gas transport processes in laboratory seawater experiments. Geophys Res Lett 36:L05603. doi:10.1029/2008GL036318

Loseto LL, Stern GA, Connelly TL, Deibel D, Gemmill B et al (2009) Summer diet of beluga whales inferred by fatty acid analysis of the eastern Beaufort Sea food web. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 374(1):12–18. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2009.03.015

Lukovich JV, Barber DG (2006) Atmospheric controls on sea ice motion in the southern Beaufort Sea. J Geophys Res 111:D18103. doi:10.1029/2005JD006408

Macdonald RW, Barrie LA, Bidleman TF, Diamond ML, Gregor DJ et al (2000) Contaminants in the Canadian Arctic: 5 years of progress in understanding sources, occurrence and pathways. Sci Total Environ 254:93–234

Macdonald R, Harner T, Fyfe J (2005) Recent climate change in the Arctic and its impact on contaminant pathways and interpretation of temporal trend data. Sci Total Environ 342(1–3):5–86

Mackay D, Fraser A (2000) Bioaccumulation of persistent organic chemicals: mechanisms and models. Environ Pollut 110:375–391

Martin S, Drucker R, Fort M (1995) A laboratory study of frost flower growth on the surface of young sea ice. J Geophys Res 100(C4):7027–7036. doi:10.1029/94JC03243

Miller LA, Carnat G, Else BGT, Sutherland N, Papakyriakou T (2011a) Carbonate system evolution at the Arctic Ocean surface during autumn freeze-up. J Geophys Res 116:C00G04. doi:10.1029/2011JC007143

Miller LA, Papakyriakou TN, Collins RE, Deming JW, Ehn JK et al (2011b) Carbon dynamics in sea ice: a winter flux time series. J Geophys Res 116:C02028. doi:10.1029/2009JC006058

Mundy CJ, Gosselin M, Ehn J, Gratton Y, Rossnagel A et al (2009) Contribution of under-ice primary production to an ice-edge upwelling phytoplankton bloom in the Canadian Beaufort Sea. Geophys Res Lett 36(17):L17601. doi:10.1029/2009gl038837

Mymrin NI, Huntington HP, Community of Novoe Chaplino, Community of Sireniki, Community of Uelen, Community of Yanrakinnot (1999) Traditional knowledge of the ecology of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in the Northern Bering Sea, Chukotka, Russia. Arctic 52(1):62–70

Nghiem SVV, Rigor IGG, Richter A, Burrows JPP, Shepson PBB, Bottenheim JW, Barber DGG, Steffen A, Latonas JR, Wang F, Stern GA, Clemente-Colon P, Martin S, Hall DKK, Kaleschke L, Tackett PJ, Neumann G, Asplin MGG (2012) Field and satellite observations of the formation and distribution of Arctic atmospheric bromine above a rejuvenated sea ice cover. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2011JD016268

Nomura D, Eicken H, Gradinger R, Shirasawa K (2010) Rapid physically driven inversion of the air-sea ice CO2 flux in the seasonal landfast ice off Barrow. Alaska after onset of surface melt. Cont Shelf Res 30:1998–2004. doi:10.1016/j.csr.2010.09.014

Obbard ME, Cattet MRL, Moody T, Walton LR, Potter D et al (2006) Temporal trends in the body condition of Southern Hudson Bay polar bears. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Applied Research and Development Branch, Sault Ste. Marie, Canada, Climate Change Research Information Note 3. Available from http://sit.mnr.gov.on.ca

Obbard ME, McDonald TL, Howe EJ, Regehr EV, Richardson ES (2007) Polar bear population status in Southern Hudson Bay, Canada. US Geological Survey Administrative Report, Reston, USA [http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/special/polar_bears/docs/USGS_PolarBear_Obbard_SHudsonBay.pdf, accessed 12 December 2008]

Palmer MA, Arrigo KR, Mundy CJ, Gosselin M, Brunelle CB et al (2011; In press) Spatial and temporal variation of photosynthetic parameters in natural phytoplankton assemblages in the Beaufort Sea, Canadian Arctic. Polar Biol

Pomerleau C, Ferguson SH, Walkusz W (2011) Stomach contents of Bowhead Whales (Balaena mysticeus) from four locations in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Biol 34:615–620. doi:10.1007/s00300-010-0914-9

Parkinson CL, Cavalieri D (2008) Arctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979–2006. J Geophys Res 113:C07003. doi:10.1029/2007JC004558

Papakyriakou T, Miller L (2011) Springtime CO2 exchange over seasonal sea ice in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Ann Glaciol 52(57):215–224

Polyakov IV, Beszczynska A, Carmack EC, Dmitrenko IA, Fahrbach E et al (2005) One more step toward a warmer Arctic. Geophys Res Lett 32(17):L17605. doi:10.1029/2005gl023740

Pućko M, Stern GA, Barber DG, Macdonald RW, Rosenberg B (2010a) The International Polar Year (IPY) Circumpolar Flaw Lead (CFL) system study: the importance of brine processes for α- and γ- hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) accumulation or rejection in sea ice. Atmos Ocean 48:244–262. doi:10.3137/OC318.2010

Pućko M, Stern GA, Macdonald RW, Barber DG (2010b) α- and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) measurements in the brine fraction of sea ice in the Canadian High Arctic using a sump-hole technique. Environ Sci Technol 44:9259–9264

Pućko M, Stern GA, Macdonald RW, Rosenberg B, Barber DG (2011a) The influence of atmosphere-snow-ice-ocean interactions on the levels of hexachlorocyclohexanes (HCHs) in the Arctic cryosphere. J Geophys Res 116:C02035. doi:10.1029/2010JC006614

Pućko M, Stern GA, Macdonald RW, Barber DG, Rosenberg B et al (2011b; in press) When will α-HCH disappear from the western Arctic Ocean? J Marine Systs

Regehr EV, Amstrup SC, Stirling I (2006) Polar bear population status in the southern Beaufort Sea. US Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006–1337, Reston, USA

Regehr EV, Lunn NJ, Amstrup SC, Stirling I (2007) Survival and population size of polar bears in western Hudson Bay in relation to earlier sea ice breakup. J Wildl Manag 71:2673–2683. doi:10.2193/2006-180

Regehr EV, Hunter CM, Caswell H, Amstrup SC, Stirling I (2010) Survival and breeding of polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea in relation to sea ice. J Anim Ecol 79:117–127. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01603.x

Rode KD, Amstrup SC, Regehr EV (2007) Polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea III: stature, mass and cub recruitment in relationship to time and sea ice extent between 1982 and 2006. USGS Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Administrative Report

Rothrock DA, Yu Y, Maykut GA (1999) Thinning of the Arctic sea-ice cover. Geophys Res Lett 26(23):3469–3472

Rysgaard S, Nielsen TG, Hansen BW (1999) Seasonal variation in nutrients, pelagic primary production and grazing in a high-Arctic coastal marine ecosystem, Young Sound, Northeast Greenland. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 179:13–25

Rysgaard S, Glud RN, Sejr MK, Bendtsen J, Christensen PB (2007) Inorganic carbon transport during sea ice growth and decay: a carbon pump in polar seas. J Geophys Res 112:C03016. doi:10.1029/2006JC003572

Rysgaard SJ, Bendtsen L, Pedersen H, Ramløv RG (2009) Increased CO2 uptake due to sea-ice growth and decay in the Nordic Seas. J Geophys Res 114:C09011

Rysgaard S, Bendtsen J, Delille B, Dieckmann GS, Glud RN et al (2011; in press) Sea ice contribution to the air-sea CO2 exchange in the Arctic and Southern Oceans. Tellus B

Sallon A, Michel C, Gosselin M (2011) Summertime primary production and carbon export in the southeastern Beaufort Sea during the low ice year of 2008. Polar Biol 34:1989–2005. doi:10.1007/s00300-011-1055-5

Schiedek D, Sundelin B, Readman JW, Macdonald RW (2007) Interactions between climate change and contaminants. Mar Pollut Bull 54:1845–1856

Semiletov I, Makshtas A, Akasofu S-I (2004) Atmospheric CO2 balance: the role of arctic sea ice. Geophys Res Lett 31:L05121. doi:10.1029/2003GL017996

Shadwick EH, Thomas H, Chierici M, Else B, Fransson A et al (2011) Seasonal variability of the inorganic carbon system in the Amundsen Gulf region of the southeastern Beaufort Sea. Limnol Oceanogr 56(1):303–322. doi:10.4319/lo.2011.56.1.0303

Stirling I (1980) The biological importance of polynyas in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic 33(2):303–315

Stirling I (1997) The importance of polynyas, ice edges, and leads to marine mammals and birds. J Mar Syst 10(1–4):9–21

Stirling I (2005) Reproductive rates of ringed seals and survival of pups in northwestern Hudson Bay, Canada, 1991–2000. Polar Biol 28:381–387

Stirling I, Archibald WR, DeMaster D (1977) Distribution and abundance of seals in the eastern Beaufort Sea. J Fisheries Res Board Can 34:976–988

Stirling I, Kingsley MCS, Calvert W (1982) The distribution and abundance of seals in the eastern Beaufort Sea, 1974–79. Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper, vol 47

Stirling I, Andriashek D, Calvert W (1993) Habitat preferences of polar bears in the western Canadian Arctic in late winter and spring. Polar Record 29:13–24

Stirling I, Lunn NJ, Iacozza J (1999) Long-term trends in the population ecology of polar bears in western Hudson Bay in relation to climate change. Arctic 52:294–306

Stroeve JC, Serreze MC, Holland MM, Kay JE, Maslanik J et al (2011) The Arctic’s rapidly shrinking sea ice cover: a research synthesis. Clim Change. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0101-1

Takahashi T, Sutherland SG, Wanninkhof R, Sweeney C, Feely RA et al (2009) Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2 and net sea-air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Sea Res Pt II 56(8–10):554–577. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.009

Thomas DN, Papdimitriou S, Michel C (2010) Biogeochemistry of sea ice. In: Thomas DN, Dieckmann GS (eds) Sea ice, 2nd edn. Wiley, Oxford, pp 425–467

Thomas TG, Nelson KH (1956) Concentration of brines and deposition of salts from sea water under frigid conditions. Am J Sci 254:227–238. doi:10.2475/ajs.254.4.227

Thompson DW, Wallace JM (1998) The Arctic Oscillation signature in the wintertime and geopotential height and temperature fields. Geophys Res Lett 25:1297–1300

Tremblay JE, Belanger S, Barber DG, Asplin M, Martin J et al (2011) Climate forcing multiplies biological productivity in the coastal Arctic Ocean. Geophys Res Lett 38:L18604. doi:10.1029/2011GL048825

Tremblay JE, Robert D, Varela DE, Lovejoy C, Darnis G (2012) Current state and changing trends in Canadian Arctic marine ecosystems: I. Primary production. Clim Change

Van Oostdam J, Gilman A, Dewailly E, Usher P, Wheatley B et al (2005) Human health implications of environmental contaminants in Arctic Canada: a review. Environ Sci Technol 351–352:165–246

Wanninkhof R, Asher WE, Ho DT, Sweeney C, McGillis WR (2009) Advances in quantifying air-sea gas exchange and environmental forcing. Ann Rev Mar Sci 1:213–244. doi:10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163742

Wong F, Jantunen LM, Pucko M, Papakyriakou T, Staebler R et al (2011) Air-Water exchange of anthropogenic and natural organohalogens on International Polar Year (IPY) expeditions in the Canadian arctic. Environ Sci Technol 45:876–881

Zemmelink HJ, Delille B, Tison JL, Hintsa EJ, Houghton L, Dacey JWH (2006) CO2 deposition over the multi-year ice of the western Weddell Sea. Geophys Res Lett 33, L13606. doi:10.1029/2006GL026320

Zhang X, Walsh JE, Zhang J, Bhatt US, Ikeda M (2004) Climatology and interannual variability of Arctic cyclone activity, 1948–2002. J Climate 17:2300–2317

Acknowledgements

Funding for the IPY-CFL project was provided by the Canadian International Polar Year (IPY) Federal Program Office, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Program, Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and numerous international partner organizations. Special thanks to the officers and crew of the CCGS Amundsen, whose dedication and excellence made the IPY-CFL project a unique milestone in polar marine science. Thanks also to the numerous community members of Sachs Harbour, Ulakhaktok, and Paulatuk for their participation in the IPY-CFL project.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Barber, D.G., Asplin, M.G., Papakyriakou, T.N. et al. Consequences of change and variability in sea ice on marine ecosystem and biogeochemical processes during the 2007–2008 Canadian International Polar Year program. Climatic Change 115, 135–159 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0482-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date: