Abstract

Glucose valorization to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) remains challenging in the transition towards renewable chemistry. Lewis acidic tungstite is a viable, moderately active catalyst for glucose dehydration to HMF. Literature reports a multistep mechanism involving Lewis acid catalyzed isomerization to fructose, which is then dehydrated to HMF by Brønsted acid sites. Doping tungstite with titanium and niobium improves activity by optimizing the ratio between Lewis and Brønsted acid sites.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Continuous consumption of ever-diminishing fossil resources and the negative impact on the environment associated with their combustion calls for their replacement with alternative renewable feedstocks. Lignocellulosic biomass is a promising starting material for the production of sustainable fuels and chemicals [1, 2]. Upgrading of biomass will likely revolve around a select number of platform molecules with a wide variety of downstream applications [3, 4]. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is regarded as one of the most versatile platform chemicals, its derivatives having potential applications as fuel additives, solvents and monomers for the plastics industry [5, 6].

HMF can essentially be obtained from both fructose and glucose. While fructose is easier to upgrade to HMF, it is also costly and scarce compared to glucose [7,8,9]. Glucose can be obtained from lignocellulosic biomass in relatively pure form, making it cheap and abundant compared to fructose. These aspects make glucose an attractive feedstock for HMF [10,11,12,13]. However, the upgrading of glucose to HMF is much more challenging than that of fructose [14,15,16]. While mineral acids such as HCl and H2SO4 can be used as catalysts for the conversion of either sugar to HMF in aqueous solution at elevated temperatures, especially glucose suffers from severe degradation to humins under these conditions [17,18,19]. Also, HMF can be rehydrated to levulinic acid in water of low pH [15, 18]. Sustainable HMF production from glucose thus requires specialized and atom-efficient catalysts, as simple Brønsted acids alone are ill-equipped for this purpose.

More efficient routes for glucose to HMF conversion employ a bifunctional system to isomerize glucose to the more reactive fructose prior to its dehydration. Enzymes can facilitate the isomerization, but are incompatible with the acidic conditions necessary for the dehydration. Basic and Lewis acid catalysts can also carry out the isomerization, but Lewis acids are preferred for their stability in acidic environments [20]. While such two-step approaches are viable, one-pot strategies have attracted much interest recently. Mechanistically, it is commonly assumed that the conversion of glucose proceeds via fructose as an intermediate. Lewis acids play an important role in isomerizing glucose to the more reactive fructose by stabilizing glucose in its acyclic form, facilitating a 1,2-hydride transfer and releasing fructofuranose (fructose) [21,22,23,24]. Subsequent dehydration then removes three water molecules to form HMF (Scheme 1). To optimize the selectivity, the reaction can be carried out in a biphasic or non-aqueous system, thereby shielding HMF from the acidic aqueous environment and preventing rehydration to levulinic acid [8, 16, 25].

Zeolites have been shown capable of isomerizing glucose to fructose, but require addition of a Brønsted acid to dehydrate the fructose to HMF [14]. Additionally, the synthesis of the most effective zeolite for this purpose, Sn-modified Beta, is cumbersome and requires toxic reagents such as HF [20, 26]. Additionally, zeolites are prone to framework damage when exposed to the high temperatures and aqueous media the reaction requires to proceed, diminishing its activity during prolonged reactions [27, 28]. Homogeneous catalysts including Lewis acidic metal chlorides in ionic liquids are also unattractive because of the difficulties associated with separation [29, 30].

A different branch of catalysts capable of these transformations are transition metal oxides such as TiO2, Nb2O5 and WO3. These materials are abundant and cheap, and express water-tolerant Lewis acid sites and tunable acid–base properties with promising glucose-upgrading abilities [31, 32]. Recently, we have shown that tungstite (WO3·H2O) is also a viable contender [33]. The material comprises distorted WO5·H2O octahedra, which share 4 equatorial corner oxygens to form a stacked sheet-like material with a low surface area. Perpendicular to each sheet, every W site is terminated alternatingly by a double bonded oxygen and coordinated water. Similarly to TiO2 and Nb2O5, it contains water-tolerant Lewis acid functionalities, but its Brønsted acidity is relatively weak, which limits fructose dehydration rates. Doping the material with Nb proved a key factor in enhancing its activity [33].

In this work, we explored the effect of titanium as a dopant on the activity of tungstite, based on the results found by DFT calculations [34]. The materials were characterized in detail with the aim to judge the dispersion of the dopant in the bulk and at the surface of tungstite.

2 Experimental Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Tungsten hexachloride (WCl6, 99%, Alfa Aesar), niobium pentachloride (NbCl5, 99.9%, Alfa Aesar), titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4, 99%, Sigma Aldrich) were kept in an MBraun glovebox under an inert argon atmosphere.

Titanium(IV) oxide (TiO2, Degussa P25) and niobium(V) oxide (Nb2O5, 99.5% Alfa Aesar) were used as commercial standards.

d-(-)-glucose (99%, Sigma Aldrich), 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF, 97%, Sigma Aldrich), tetrahydrofuran (THF, 99%, Biosolve), triethylamine (TEA, 99.9%, VWR) and acetonitrile (MeCN, HPLC-S grade, Biosolve) were used as received. Pyridine (Sigma Aldrich, 99%) was stored on freshly activated 3 Å molsieves (Merck).

Deionized water (15 and 18.2 MΩ) was obtained from an Elgastat Water Purifier present in our laboratory.

2.2 Catalyst Preparation

Preparation of WO3:WCl6 (3.97 g; 10.0 mmol) was dispersed in 160 mL deionized water in an open beaker in contact with air to initiate hydrolysis. The suspension was kept at 50 °C overnight while stirred magnetically. The yellow precipitate was collected by filtration and washed several times with deionized water until neutral pH of the filtrate was reached. The residue was then dried at 60 °C in vacuo overnight. NbWx (x representing W/Nb ratios of 10 and 5) samples were prepared in a similar fashion using physical mixtures of appropriate amounts of WCl6 and NbCl5. TiWx (W/Ti ratios of 10 and 5) were prepared by adding an appropriate amount of WCl6 to 160 mL water first and injecting the correct amount of TiCl4 within 10 s using a Finn pipette with the tip submerged in the water. After drying, the materials were used without further treatment.

2.3 Characterization

Elemental analysis was performed on a Spectroblue EOP ICP optical emission spectrometer with axial plasma viewing, equipped with a free-running 27.12 MHz generator operating at 1400 W. Prior to the measurement, the samples were digested using a 4 M KOH solution. For Ti containing materials an equal volume of 8 vol% HF was added to dissolve the titanium under gentle heating (~ 40 °C).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a Thermo Scientific K-alpha equipped with a monochromatic small-spot X-ray source and a 180° double focusing hemispherical analyzer with a 128-channel detector. Initial pressure was 8 × 10−8 mbar or less which increased to 2 × 10−7 mbar due to the active argon charge compensation dual beam source during measurement.

For a typical sample preparation, fresh catalyst was pressed down on carbon tape supported by an aluminium sample plate. Spectra were recorded using an AlKα X-ray source (1486.6 eV, 72 W) and a spot size of 400 µm. Survey scans were taken at a constant pass energy of 200, 0.5 eV step size, region scans at 50 eV constant pass energy with a step size of 0.1 eV.

XPS spectra were calibrated to the C–C carbon signal (284.8 eV) obtained from adventitious carbon and deconvoluted with CasaXPS. The peak areas thus obtained were used to estimate surface chemical composition.

Nitrogen sorption data was recorded on a Micrometrics Tristar 3000 in static measurement mode at − 196 °C. The samples (typically 150 mg) were pretreated at 120 °C under a gentle N2 stream overnight prior to the sorption measurements. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation was used to calculate the specific surface area (SBET) from the adsorption data (p/p0 = 0.05–0.25).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained in bright field mode from a FEI Tecnai 20 (type Sphera) operating with a LaB6 filament at 200 kV and a bottom mounted 1024 × 1024 Gatan msc 794™ CCD camera and elemental mapping was performed on a probe Cs corrected Titan2 (FEI) operating at 300 kV in ADF-STEM mode using an Oxford Instruments X-MaxN 100TLE EDX detector. Suitable samples were prepared by dropping a suspension of finely ground material in analytical grade absolute ethanol onto Quantifoil R 1.2/1.3 holey carbon films supported on a copper grid.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker Endeavour D2 Phaser diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation with a scanning speed of 0.6° min−1 in the range of 5° ≤ 2θ ≤ 60°. Crystal phases were identified using the DIFFRAC.EVA software package and the PDF-2 crystallographic database (version 2008).

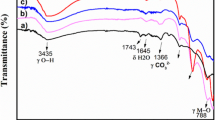

Fourier-transformed infrared (FT-IR) was used to evaluate acidic properties of the materials. Spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–1200 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1 on a Bruker Vertex V70v equipped with a DTGS detector and CaF2 windows. A total of 64 scans were averaged for each spectrum. Typically, finely powdered material was pressed into self-supporting wafers with density ρ ≃ 25 mg cm−2 using a pressing force of 3000 kg, and placed inside a variable temperature IR transmission cell coupled to a closed gas circulation system. The samples were then outgassed at 70 °C in vacuo until a pressure of 2 × 10−5 mbar or lower was reached.

Prior to pyridine adsorption, the sample was kept at 70 °C and a sample background was recorded. Pyridine was then introduced into the cell until saturation was reached, and physisorbed pyridine was removed in vacuo for 1 h. A second spectrum were recorded in situ at this point.

Difference spectra were obtained by subtraction of the sample background from the recorded spectra. Processing and deconvolution of the signals was performed with Fityk curve fitting program.

2.4 Catalytic Activity Tests

Batch reactions were performed at 120 °C under autogenous pressure in Pyrex tubes (inner volume 12 mL) equipped with a magnetic stirring bar. For a typical experiment, 5 tubes were each charged with 40 mg glucose dissolved in 4 mL of a biphasic H2O/THF mixture, volume ratio 1/9, in which 40 mg of catalyst was suspended and sealed with a PTFE stopper. After a corresponding reaction time, the reaction was quenched by immersion of the tube in an ice/water bath. Reaction times of 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 min were used.

Aliquots were filtered through a 0.45 µm PTFE filter and analyte concentrations were determined by a Shimadzu HPLC system equipped with autosampler and column oven. Glucose and fructose were separated on a Shodex Asahipak NH2P-50 2D kept at 35 °C and detected by ELSD (ELSD-LT II operating at 40 °C, gas pressure 350 kPa) using 70:30 MeCN:H2O modified with 0.001 M TEA as mobile phase (0.2 mL min−1). HMF was measured by UV–Vis (SPD-M20A operating at 40 °C, λmax 284 nm) using a Phenomenex Kinetex 5u EVO C18 100A reversed phase column at 40 °C for separation and 5:95 MeCN:H2O as mobile phase (0.4 mL min−1).

Conversion, yield and selectivities of the respective compounds were calculated using the following formulas and converted to percentages when appropriate:

where X is the conversion of glucose, YP the product yield, n0 and nt the glucose concentrations at t = 0 and t = reaction time, and nP the product concentration.

3 Results and Discussion

Hydrolysis of WCl6 in water initially yielded a gray suspension, which turned yellow overnight. Collection and drying of the formed material provided a vividly yellow, easy to disperse solid. Hydrolysis of the NbCl5/WCl6 physical mixtures behaved similarly and yielded similarly yellow colored, more voluminous oxides NbW10 and NbW5 (W/Nb = 10 or 5). On the other hand, the synthesis of TiW10 and TiW5 (W/Ti = 10 or 5) yielded pale-yellowish, very dense, grainy materials.

XPS and ICP results are summarized in Table 1. All doped materials contain the desired amount of dopant as evidenced by ICP. The bulk and surface W/Nb ratios of NbW10 and NbW5 match quite well, indicating no surface segregation. However, the content of titanium in the bulk of the TiWx samples is significantly higher than the surface content. Deconvolution of the tungsten 4f region yields two separate W 4f7/2/W 4f5/2 doublets, presented in Fig. 1. For the W 4f7/2 peaks, the binding energies were 34.8 and 35.9 eV, which could be assigned to WV and WVI oxidation states, respectively [35]. Deconvolution of the peaks related to the dopants (Nb 3d and Ti 2p) yielded a single doublet for either material. Binding energies for the Nb 3d5/2 and Ti 2p3/2 components were 207.6 and 459.2 eV and were assigned to the fully oxidated states (NbV and TiIV) [36, 37].

XPS spectra of the as-prepared materials. Experimental data are represented by open circles and the fit as a black curve. W 4f fits are composed of WVI (blue) and WV (green). Nb 4p and Ti 3p fits overlapping with the W 4f region are indicated in red. Dopant Ti 2p and Nb 3d fits are displayed in blue

Of note is that the amount of WV species differs from material to material. The undoped oxide contains ~ 5.6% as WV. Increasing levels of Nb raise the level of WV to 6.9% for NbW10 (W/Nb ratio of 10) and to 11% for NbW5 (W/Nb ratio of 5). Reduction of W due to the inclusion of niobium has been described before [38, 39]. Doping WO3 with Ti also increased the WV content, but to a lesser extent. Care was taken to include the Nb 4p and Ti 3p regions, since both overlap with the W 4f region and would present incorrect WVI/WV ratios if excluded [40]. Finally, no surface chlorine was present on the samples, indicated by the absence of the Cl 2p signal.

Textural properties of the bulk materials were evaluated using N2 physisorption. Surface areas are summarized in Table 2. NbW5 has the highest surface area (35 m2 g−1) and TiW5 the lowest (5 m2 g−1). Isotherms of all materials, displayed in Fig. 2, were of the type IV shape with a H3 hysteresis loop, indicative of aggregates of plate-like materials forming slit-like macropores.

TEM micrographs present a sheet-like morphology for WO3, NbW5 and TiW5 (Fig. 3), which is in keeping with the physisorption measurements. The sheets of WO3 and NbW5 have well-defined edges in contrast to the quite corrugated plane edges of TiW5.

The XRD pattern of WO3 (Fig. 4) shows that it consists primarily of tungstite [PDF 043-0679] with hydrotungstite [PDF 018-1420] as a minor fraction. Both phases consist of stacked planes built up of equatorial corner-sharing WO5·H2O octahedral and each plane is terminated with alternating double bonded oxygen or coordinated H2O. The planes are held together by hydrogen bonds. The phases primarily differ in an extra layer of water intercalated between every two hydrotungstite planes. Both NbW10 and NbW5 materials comprise a pure hydrotungstite phase, decreasing in crystallinity with increasing Nb content. TiW10 and TiW5 are mostly amorphous, although a hydrotungstite phase can still be identified in both samples. Probably, this is caused by the tetrahedral coordination that TiIV can adopt, disrupting the otherwise planar tungstite layers [34]. Substituting WVI with NbV on the other hand will maintain the planar ordering as NbV can take on a square pyramidal coordination with four equatorially placed oxygens. The planar morphology of all materials affirm the findings found with sorption and TEM measurements. No Nb2O5 or TiO2 phases were found in the diffractograms, showing full incorporation of the dopants into the WO3 framework. This was additionally confirmed by aid of STEM–EDX. Although minor inhomogeneities were observed, no segregation between dopant oxides and tungstite could be detected (Fig. 5).

Previous work shows that doping WO3 with niobium increased the Brønsted acidity of the material [33]. The exchange of Lewis acidic WVI cations by NbV species induces a charge defect which is compensated by acidic protons, thus increasing the amount of Brønsted acid sites (BAS). Concurrently, this exchange decreased the number of Lewis acid sites (LAS) as the relative amount of WVI is lowered.

The as-produced materials were therefore analyzed on acidic properties using pyridine as probe molecule using integrated molecular absorption coefficients as established by Datka et al. [41] Results are presented in Table 2. Expectedly, undoped WO3 has the highest density of LAS, but also possesses a reasonable density of BAS. The latter are likely derived from the partial reduction of WVI to WV. Generally, increasing amounts of either dopant lowers the amount of LAS and increases the amount of BAS. Additionally, the effects of Ti doping are more pronounced than inclusion of Nb. Where NbW10 presents only a minor decrease in LAS and actually a lower density of BAS, TiW10 loses roughly half of its LAS and possesses more than double the amount of BAS compared to undoped WO3. This trend continues in TiW5 where the density of LAS is reduced slightly and the BAS density is double that of TiW10. We expect that the inclusion of Ti4+ induces a larger charge defect as compared to that Nb5+, which in the extreme case needs compensation by two acidic protons instead of one.

Activity tests of the five materials are displayed in Fig. 6. All materials were able to reach full glucose conversion within 4 h. The conversion rate was substantially higher for the doped materials. Undoped WO3 exhibits a poor selectivity to HMF, evidenced by the low yield of 15% after 4 h of reaction (Fig. 6, left graph). Addition of HCl after 3 h increased the yield to 55%, indicating that the Brønsted acidity of the undoped oxide is too low to efficiently perform the dehydration steps. In contrast, the doped materials were all able to complete this dehydration unaided and with a much higher activity, leading to selectivities of roughly 55–60%. The remainder of the converted glucose is inadvertently lost due to side-product formation such as humins, which can form from glucose, 5-HMF, fructose and other intermediates. Interestingly, the TiWx and NbWx materials perform equally well, although TiWx has an order of magnitude lower surface area than NbWx. This can be ascribed to the substantially higher density of BAS in TiWx.

Activity plots of undoped WO3 (left), NbWx (center) and TiWx (right). Squares represent glucose conversion, and circles and triangles represent HMF and fructose yield respectively. Closed circle for leftmost graph represents HMF yield when no HCl is added after 3 h of reaction time. Gray and black lines in center and right graph represent activity data for W/dopant = 5 and 10 respectively

As control experiments, the catalytic performance of commercial Nb2O5 and TiO2 powders was tested using the same conditions as for the undoped and doped WO3 oxides (Fig. 7). Niobia and titania convert glucose relatively fast, as no trace of glucose is found after 30 min of reaction. Fructose was also not detected at any stage. HMF yields for niobia and titania remain steady after 30 min at respectively 22 and 0.6%, much lower than any of the tungsten-based oxides. This shows that doped tungsten oxides are a promising material for the promotion of glucose dehydration to 5-HMF.

From the activity data and the literature insights on glucose dehydration mechanism, we can deduce that Lewis acid sites catalyze the initial isomerization step of glucose to fructose [18, 22, 32, 34, 42]. This leads to fructose as an intermediate. In most experiments, the maximum fructose yield is observed after a reaction time of 30 min. The yield is relatively low in all cases, indicating that fructose is rapidly converted to other products. The remaining steps to obtain 5-HMF from fructose entail dehydration steps, which are catalyzed by Brønsted acid sites.

4 Conclusions

Undoped tungsten oxide and niobium- and titanium-doped tungsten oxides were successfully prepared by aqueous precipitation of WCl6, NbCl5 and TiCl4 with final tungsten/dopant ratios close to desired ratios (5 or 10). The dopants were shown to substantially impact the physicochemical parameters, most notably on surface area and crystal morphology. Niobium improved the surface area, i.e. replacing 20% of tungsten by niobium led to a two times higher surface area. In contrast, inclusion of 10% of titanium significantly lowered the surface area. Undoped WO3 comprises a tungstite crystal phase, while doped materials additionally contained a hydrotungstite phase. Separate Nb2O5 and TiO2 phases were not detected and the dopants were quite homogeneously distributed throughout the materials. Both niobium and titanium led to increased Brønsted acid site densities of the tungstite phase, which had a positive effect on glucose dehydration, although the final 5-HMF selectivities were mostly unaffected. Optimized 5-HMF selectivities were in the 55–60% range, the remainder being humins. Interestingly, while both TiW5 and NbW5 have comparable HMF formation rates, their surface areas differ by an order of magnitude. This indicates that TiW5 is significantly more active on a surface area base, which is explained by the relatively high density of Brønsted acid sites. Compared to titania and niobia reference materials that display high glucose conversion rates but low 5-HMF selectivity, doped WO3 stand out as cheap materials with a high density of Lewis and Bronsted acid sites for efficient conversion of glucose to 5-HMF.

References

Corma Canos A, Iborra S, Velty A (2007) Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals. Chem Rev 107:2411–2502

Kobayashi H, Ohta H, Fukuoka A (2012) Conversion of lignocellulose into renewable chemicals by heterogeneous catalysis. Catal Sci Technol 2:869. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2cy00500j

Bozell JJ, Petersen GR (2010) Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates—the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited. Green Chem 12:539. https://doi.org/10.1039/b922014c

Gallezot P (2012) Conversion of biomass to selected chemical products. Chem Soc Rev 41:1538–1558. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1CS15147A

Rosatella AA, Simeonov SP, Frade RFM, Afonso CAM (2011) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) as a building block platform: biological properties, synthesis and synthetic applications. Green Chem 13:754. https://doi.org/10.1039/c0gc00401d

Van Putten RJ, Van Der Waal JC, De Jong E et al (2013) Hydroxymethylfurfural, a versatile platform chemical made from renewable resources. Chem Rev 113:1499–1597. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300182k

Qi X, Watanabe M, Aida TM, Smith RL Jr (2009) Efficient process for conversion of fructose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural with ionic liquids. Green Chem 11:1327. https://doi.org/10.1039/b905975j

Chheda JN, Román-Leshkov Y, Dumesic JA (2007) Production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural by dehydration of biomass-derived mono- and poly-saccharides. Green Chem 9:342–350. https://doi.org/10.1039/B611568C

Wach W (2004) Fructose. In: Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, pp 103–115

Meine N, Rinaldi R, Schüth F (2012) Solvent-free catalytic depolymerization of cellulose to water-soluble oligosaccharides. ChemSusChem 5:1449–1454. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201100770

Rinaldi R, Palkovits R, Schüth F (2008) Depolymerization of cellulose using solid catalysts in ionic liquids. Angew Chem Int Ed 47:8047–8050. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200802879

Wang J, Xi J, Wang Y (2015) Recent advances in the catalytic production of glucose from lignocellulosic biomass. Green Chem 17:737–751. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4GC02034K

vom Stein T, Grande PM, Kayser H et al (2011) From biomass to feedstock: one-step fractionation of lignocellulose components by the selective organic acid-catalyzed depolymerization of hemicellulose in a biphasic system. Green Chem 13:1772. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1gc00002k

Nikolla E, Román-Leshkov Y, Moliner M, Davis ME (2011) “One-pot” synthesis of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural from carbohydrates using tin-beta zeolite. ACS Catal 1:408–410. https://doi.org/10.1021/cs2000544

Choudhary V, Mushrif SH, Ho C et al (2013) Insights into the interplay of Lewis and Brønsted acid catalysts in glucose and fructose conversion to 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural and levulinic acid in aqueous media. J Am Chem Soc 135:3997–4006. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja3122763

Zhao H, Holladay JE, Brown H, Zhang ZC (2007) Metal chlorides in ionic liquid solvents convert sugars to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Science 316:1597–1600. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1141199

Girisuta B, Janssen LPBM, Heeres HJ (2006) Green chemicals. Chem Eng Res Des 84:339–349. https://doi.org/10.1205/cherd05038

Garcés D, Díaz E, Ordóñez S (2017) Aqueous phase conversion of hexoses into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and levulinic acid in the presence of hydrochloric acid: mechanism and kinetics. Ind Eng Chem Res 56:5221–5230. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00952

Rasrendra CB, Windt M, Wang Y et al (2013) Experimental studies on the pyrolysis of humins from the acid-catalysed dehydration of C6-sugars. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 104:299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2013.07.003

Moliner M, Román-Leshkov Y, Davis ME (2010) Tin-containing zeolites are highly active catalysts for the isomerization of glucose in water. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:6164–6168. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1002358107

Pidko EA, Degirmenci V, Van Santen RA, Hensen EJM (2010) Glucose activation by transient Cr2+ dimers. Angew Chem Int Ed 49:2530–2534. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201000250

Yang G, Pidko EA, Hensen EJM (2012) Mechanism of Bronsted acid-catalyzed conversion of carbohydrates. J Catal 295:122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2012.08.002

Yang G, Pidko EA, Hensen EJM (2013) The mechanism of glucose isomerization to fructose over Sn-BEA zeolite: a periodic density functional theory study. ChemSusChem 6:1688–1696. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201300342

Zhang Y, Pidko EA, Hensen EJM (2011) Molecular aspects of glucose dehydration by chromium chlorides in ionic liquids. Chem A Eur J 17:5281–5288. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201003645

Zhao Q, Wang L, Zhao S et al (2011) High selective production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose by a solid heteropolyacid catalyst. Fuel 90:2289–2293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.02.022

Corma A, Nemeth LT, Renz M, Valencia S (2001) Sn-zeolite beta as a heterogeneous chemoselective catalyst for Baeyer-Villiger oxidations. Nature 412:423–425. https://doi.org/10.1038/35086546

Zapata PA, Huang Y, Gonzalez-Borja MA, Resasco DE (2013) Silylated hydrophobic zeolites with enhanced tolerance to hot liquid water. J Catal 308:82–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2013.05.024

Ravenelle RM, Schübler F, Damico A et al (2010) Stability of zeolites in hot liquid water. J Phys Chem C 114:19582–19595. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp104639e

Eminov S, Brandt A, Wilton-Ely JDET, Hallett JP (2016) The highly selective and near-quantitative conversion of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using ionic liquids. PLoS ONE 11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163835

Wang H, Liu S, Zhao Y et al (2016) Molecular origin for the difficulty in separation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from imidazolium based ionic liquids. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 4:6712–6721. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b01652

Noma R, Nakajima K, Kamata K et al (2015) Formation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural by stepwise dehydration over TiO2 with water-tolerant Lewis acid sites. J Phys Chem C 119:17117–17125. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03290

Nakajima K, Baba Y, Noma R et al (2011) Nb2O5·nH2O as a heterogeneous catalyst with water-tolerant lewis acid sites. J Am Chem Soc 133:4224–4227. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja110482r

Yue C, Li G, Pidko EA et al (2016) Dehydration of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using Nb-doped tungstite. ChemSusChem. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201600649

Li G, Pidko EA, Hensen EJM (2016) A periodic DFT study of glucose to fructose isomerization on tungstite (WO3·H2O): influence of group IV-VI dopants and cooperativity with hydroxyl groups. ACS Catal 6:4162–4169. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.6b00869

Vasilopoulou M, Palilis LC, Georgiadou DG et al (2011) Reduction of tungsten oxide: a path towards dual functionality utilization for efficient anode and cathode interfacial layers in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv Funct Mater 21:1489–1497. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201002171

Dash JK, Chen L, Topka MR et al (2015) A simple growth method for Nb2O5 films and their optical properties. RSC Adv 5:36129–36139. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA05074J

Krishnan P, Liu M, Itty PA et al (2017) Characterization of photocatalytic TiO2 powder under varied environments using near ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Sci Rep 7:43298. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43298

Yue C, Zhu X, Rigutto M, Hensen E (2015) Acid catalytic properties of reduced tungsten and niobium-tungsten oxides. Appl Catal B 163:370–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2014.08.008

Bathe SR, Patil PS (2007) Influence of Nb doping on the electrochromic properties of WO3 films. J Phys D 40:7423–7431. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/23/025

Alexander V, Naumkin AKraut-Vass, Stephen W. Gaarenstroom CJP (2017) NIST X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database, NIST Standard Reference Database 20, Version 4.1. http://srdata.nist.gov/xps/Default.aspx. Accessed 20 Dec 2017

Datka J, Turek AM, Jehng JM, Wachs IE (1992) Acidic properties of supported niobium oxide catalysts: an infrared spectroscopy investigation. J Catal 135:186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9517(92)90279-Q

Saha B, Abu-Omar MM (2014) Advances in 5-hydroxymethylfurfural production from biomass in biphasic solvents. Green Chem 16:24–38. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3GC41324A

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge A.M. Elemans-Mehring for assistance with the ICP measurements and M.W.G.M Verhoeven for support with XPS processing. Further thanks are extended to F.D. Tichelaar of NCHREM at Delft University of Techology for performing the STEM–EDX experiments. This work was supported by the Netherlands Center for Multiscale Catalytic Energy Conversion (MCEC), an NWO Gravitation programme funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of the government of the Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiesfeld, J.J., Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M. & Hensen, E.J.M. Early Transition Metal Doped Tungstite as an Effective Catalyst for Glucose Upgrading to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural. Catal Lett 148, 3093–3101 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-018-2483-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-018-2483-4