Abstract

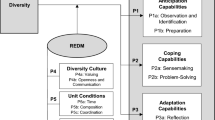

Workforce diversity has received increasing amounts of attention from academics and practitioners alike. In this article, we examine the empirical association between a firm’s workforce diversity (hereafter, diversity) and the degree of religiosity of the firm’s management by investigating their unidirectional and endogenous effects. Employing a large and extensive U.S. sample of firms from the years 1991–2010, we find a positive association between a measure of the firm’s commitment to diversity and the religiosity of the firm’s management after controlling for various firm characteristics. In addition, after controlling for endogeneity with the dynamic panel generalized method of moment, we still find a positive association between the firm’s diversity and management’s religiosity. We interpret these results as supportive of the religious motivation explanation that views the firm as a human community and considers religion as a factor that influences managers to more positively embrace diversity. Our results, however, provide no support for the resource-constraint hypothesis that views the firm as a nexus of contracts and sees managers as aiming to maximize shareholder returns under resource constraints that force them to invest only in projects that have a positive net present value (NPV) and reject diversity initiatives since these do not have a positive NPV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This kind of diversity is generally called “demographic” diversity, a term we define below.

We define religiosity, following McDaniel and Burnett (1990), as a belief in God accompanied by a commitment to follow principles believed to be set by God. Also following McDaniel and Burnett we measure religiosity in behavioral terms as frequency of church attendance.

The exact origin of the term Protestant is unsure, and may come either from French protestant or German Protestant (Online etymology dictionary 2012). However, it is certain that both languages derived their word from the Latin: protestantem, meaning “one who publicly declares/protests”, which refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms in 1521, banning Martin Luther’s 95 theses of protest against some beliefs and practices of the early 16th century Catholic Church..

Popes were writing encyclicals long before the nineteenth century, of course, but the first encyclical to explicitly address social issues was the 1891 encyclical The Condition of Labor. Other sources of Catholic Social Teachings besides the encyclicals include the teachings of Church Councils such as the Second Vatican Council, the addresses of the popes, and official publications and summaries such as the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church.

Another issue that may seem to clash with the idea that the Christian denominations in the U.S. are supportive of diversity is the fact that most U.S. congregations today are racially segregated. However, although congregations remain segregated, during the last two decades they have made substantial efforts to integrate themselves, particularly through the “reconciliation” movements the churches launched during the 1990s. The reasons why they remain segregated in spite of the efforts both white and black congregations have made to integrate their memberships are not completely clear. However, we note here that our claim is that the Christian denominations have supported diversity in business organizations, even if they have failed to make their own organizations more diverse.

Because KLD increased its sample size substantially by including the Russell 1000 in 2001 and the Russell 2000 in 2003, the results for the diversity measures in 2001 and 2003 may not be stable due to the large increase in the number of firms in the sample. As a robustness check, we have also excluded 2001 and 2003 from the sample. Overall, our untabulated results are robust to the exclusion of 2001 and 2003.

To check the existence of potential interpolation bias, we conduct our regressions using only the years for which we have direct survey data on religiosity (1990 and 2000) in our unreported results. Though the sample size is much smaller, the significant association between diversity and religiosity measure suggests that our linear interpolation does not create systematic noise in our main results.

The dynamic panel GMM model, in particular, enables us to estimate the diversity-religiosity relation by dealing with (i) past diversity scores due to autocorrelation problem of diversity ratings, (ii) fixed-effects to account for the dynamic aspects of the diversity-religiosity relation, and (iii) time-invariant unobservable heterogeneity, respectively.

As suggested earlier, based on direct survey data on religiosity (1990 and 2000), we find the significant and positive relation between diversity and religiosity measure, indicating that our linear interpolation process does not create systematic bias in our main results..

References

Agnew, R. (1998). The approval of suicide: A social psychological model. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior, 28, 205–225.

Albrecht, S. L., Chadwick, B. A., & Alcorn, D. S. (1977). Religiosity and deviance. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 16, 263–274.

Allport, G., & Ross, J. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 447–457.

Armstrong, C., Flood, P. C., Guthrie, J. P., Liu, W., Maccurtain, S., & Mkamwa, T. (2010). The impact of diversity and equality management on firm performance. Human Resource Management, 49(6), 977–998.

Baier, C., & Wright, B. (2001). If you love me keep my commandments: A meta-analysis of the effect of religion on crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38, 3–21.

Bantel, K. A., & Jackson, S. E. (1989). Top management and innovations in banking: Does the composition of the top team make a difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10, 107–124.

Barkan, S. E. (2006). Religiosity and premarital sex in adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 407–417.

Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P., & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the individual: A social-psychological perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bearman, P. S., & Bruckner, H. (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology, 4, 859–912.

Bolton, P., Scheinkman, J., & Xiong, W. (2006). Executive compensation and short termist behavior in speculative markets. Review of Economic Studies, 73(3), 577–610.

Brownfield, D., & Sorenson, A. M. (1991). Religion and drug use among adolescents: A social support conceptualization and interpretation. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12, 259–276.

Butler, S. (2013). Five steps for seating women at the boardroom table. Network of Executive Women. April 24.

Carter, D. A., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review, 38(1), 33–53.

Chadwick, B. A., Top, B. L., & McClendon, R. J. (2010). Shield of faith: The power of religion in the lives of LDS youth and young adults. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center.

Chatman, J. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 459–484.

Chatterji, A., Levine, D., & Toffel, M. (2009). How well do social ratings actually measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 18, 125–169.

Chavez, C. I., & Weisinger, J. Y. (2008). Beyond diversity training: A social infusion for cultural inclusion. Human Resource Management, 47, 331–350.

Cheng, Q., & Warfield, T. (2005). Equity incentives and earnings management. Accounting Review, 80(2), 441–476.

Christian, J., Porter, L. W., & Moffitt, G. (2006). Workplace diversity and group relations: An overview. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9(4), 459–466.

Coase, R. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4, 386–405. (Reprinted in The nature of the firm: Origins, evolution, and development: 1961–1974, by O. E. Williamson & S. G. Winter, Eds., 1991, New York: Oxford University Press).

Cochran, J. K., & Akers, R. L. (1989). Beyond hellfire: An exploration of the variable effects of religiosity on adolescent alcohol and marijuana use. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 26(3), 198–225.

Cole, B. & Salimath, M. (2012). Diversity identity management: Organizational perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics (in press).

Cox, T. (2001). Creating the multicultural organization: A strategy for capturing the power of diversity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cox, T. H., Lobel, S. A., & Mcleod, P. L. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 827–847.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2004). Business ethics, a European perspective: managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the age of globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dezso, C. L., & Ross, D. G. (2012). Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strategic Management Journal, 33(9), 1072–1089.

Dhaliwal, D., Oliver, L., Tsang, A., & Yang, G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100.

Donahue, M. J., & Benson, P. L. (1995). Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 145–160.

Dyreng, S., Mayew, W. J., & Williams, C. D. (2010). Religious social norms and corporate financial reporting. Working paper.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, Ni,Y., Pittman, J., & Saadi, S. (2012). Does religion matter to equity pricing? Journal of Business Ethics (in press).

Ellingsen, M. (1993). The Cutting edge: How churches speak on social issues. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Ellison, C. G., Burr, J. A., & McCall, P. (1997). Religion homogeneity and metropolitan suicide rates. Social Forces, 76, 273–299.

Emerson, M. O., & Sikkink, D. (2006). Portraits of American Life Study, 1st Wave, 2006.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–197.

Fastnow, C., Grant, J., & Rudolph, T. (1999). Holy roll calls: religious tradition and voting behavior in the U.S. House. Social Science Quarterly, 80, 687–701.

Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. C. (1996). Strategic leadership: Top executives and their effects on organizations. New York: West Publishing Company.

Finn, D. (2012). Human work in Catholic social thought. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 71(4), 874–885.

Freeman, D. D. (2001). Fifty years of social and ethical perspectives and teachings. Prism: A theological forum for the United Church of Christ, 21(2), 46–74.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York times Magazine, September 13, 1970.

Geyer, A., & Baumeister, R. (2005). Religion, morality, and self-control. In F. Raymond & L. Crystal (Eds.), The Handbook of Religion and Spirituality (pp. 412–432). New York: The Guiford Press.

Gibson, K. (2000). The moral basis of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 245–257.

Gibson, D. (2005). September, spirituality in America: God on the job? Ladies Home Journal.

Grasmick, H. G., Kinsey, K., & Cochran, J. K. (1991). Denomination, religiosity and compliance with the law: A study of adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30(1), 99–107.

Greeley, A., & Hout, M. (2006). The truth about conservative Christians. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Greeley, A., McCready, W., Sullivan, T., & Fee, J. (1981). The young catholic adult. New York: Sadlier Press.

Grinstein, Y., Weinbaum, D., & Yehuda, N. (2011). The economic consequences of perk disclosure. Unpublished working paper, Johnson School, Cornell University.

Grullon, G., Kanatas, G., & Weston, J. (2010). Religion and corporate (mis)behavior. Working paper.

Hansen, F. (2003). Diversity’s business case doesn’t add up. Workforce, 82(4), 28–32.

Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. (2007). What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1199–1228.

Herring, C. (2009). Does diversity pay? Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 208–224.

Hilary, G., & Hui, K. (2009). Does religion matter in corporate decision making in America? Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 455–473.

Hirschi, T., & Stark, R. (1969). Hellfire and delinquency. Social Problems, 17, 202–213.

Hirschl, T. A., Booth, J. G., & Glenna, L. L. (2009). The link between voter choice and religious identity in contemporary society: Bringing classical theory back In. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 927–944.

Hubbard, E. E. (2004). The Diversity scorecard: Evaluating the impact of diversity on organizational performance. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinmann.

Huffman, T. (1988). In the world but not of the world: Religious alienation, and philosophy of human nature among Bible college and liberal arts college students (Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa) dissertation.

Hunt, R. A., & King, M. (1971). The intrinsic-extrinsic concept: A review and evaluation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 10(4), 339–356.

Hunt, S., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 8, 5–16.

Hunt, S., & Vitell, S. (1993). The general theory of marketing ethics: A retrospective and revision. In S. N. Craig & J. A. Quelch (Eds.), Ethics in marketing (pp. 775–784). Homewood, IL: Irwin Inc.

Iannaccone, L. (1998). Introduction to the economics of religion. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 1465–1496.

IBM. (2013). Diversity & Inclusion. [IBM diversity brochure]. Accessed July 10 at http://www-03.ibm.com/employment/us/diverse/downloads/ibm_diversity_brochure.pdf.

ILO [International Labor Organization]. (2012). Convergences: Decent work and social justice in religious traditions, a handbook. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Organization.

Ioannou, I. & Serafeim, G. (2010). The impact of corporate social responsibility on investment recommendations, Harvard Business School Working Paper No 11-017. Available at http://www.hbs.edu/research/pdf/11-017.pdf.

Jackson, S. E., Brett, J. F., Sessa, V. I., Cooper, D. M., Julin, J. A., & Peyronnin, K. (1991). Some differences make a difference: Interpersonal dissimilarity and group heterogeneity as correlates of recruitment, promotion, and turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 675–689.

Jackson, S. E., Joshi, A., & Erhardt, N. L. (2003). Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management, Winter.

Jehn, A., Northcraft, G., & Neale, M. (1999). Why difference makes a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 741–763.

Jelen, T. G. (1998). Research in religion and mass political behavior in the United States: Looking both ways after two decades of scholarship. American Politics Quarterly, 26(1), 110–134.

Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Jeynes, W. H. (2003). The effects of religious commitment on the attitudes and behavior of teens regarding premarital childbirth. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 17(1), 1–17.

Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. (2011). Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(3), 351–383.

Jo, H., & Harjoto, M. (2012). The causal effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 53–72.

John Paul II, (1984). Address of John Paul II to Members of the Special Committee of the United Nations Organization Against Apartheid, July 7, 1984. Accessed May 10, 2013. http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/1984/july/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19840707_onu-apartheid_en.html.

John Paul II (1991) Centesimus Annus [On the Hundredth Anniversary]. Encyclical accessed April 17, 2013 at www.vatican.va.

Kacperczyk, M. (2009). With greater power comes greater responsibility? Takeover protection and corporate attention to stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 261–285.

Kaler, J. (2002). Morality and strategy in stakeholder identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 39(1), 91–99.

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelley, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity practices. American Sociological Review, 71(4), 589–617.

Kennedy, E. & Lawton, L. (1998). Religiousness and business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics Dordrecht, 17 (January 2), 163–175.

Kochan, T., Bezrukova, K., Ely, R., Jackson, S., Joshi, A., & Jehn, K. (2003). The effects of diversity on business performance: Report of the diversity research network. Human Resource Management, 42, 3–21.

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays on moral development, 1: The philosophy of moral development, moral stages and the idea of justice. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Konrad, A. M., Winter, S., & Gutek, B. A. (1992). Diversity in work group sex composition: implications for majority and minority members. In P. Tolbert & S. B. Bacharach (eds.), Research in the sociology of organizations, Vol. 13, pp. 191–228.

Kosmin, B. & Keysar, A. (2009). American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008), Trinity College, Hartford, CN: Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture.

Kumar, A., Page, J., & Spalt, O. (2011). Religious beliefs, gambling attitudes, and financial market outcomes. Journal of Financial Economics, 102, 671–708.

Kutcher, E., Bragger, J., Rodriguez-Srednicke, O., & Masko, J. (2010). The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 319–337.

Larkey, L. K. (1996). Toward a theory of communicative interactions in culturally diverse workgroups. Academy of Management Review, 21, 463–491.

Leege, D., & Kellstedt, L. (1993). Rediscovering the religious factor in American politics. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Leege, D. C., & Welch, M. R. (1989). Religious roots of political orientations. Journal of Politics, 51(1), 137–162.

Manza, J., & Brooks, C. (1997). The religious factor in U.S. presidential elections, 1960-1992. The American Journal of Sociology, 103, 38–81.

McCabe, D., & Trevino, L. (1993). Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. Journal of Higher Education, 64(5), 523–538.

McDaniel, S., & Burnett, J. (1990). Consumer religiosity and retail store evaluative criteria. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18, 101–112.

McGuire, S., Newton, N., Omer, T., & Sharp, N. (2012b). Does local religiosity impact corporate social responsibility? Working paper.

McGuire, S., Omer, T., & Sharp, N. (2012a). The impact of religion on financial reporting irregularities. Accounting Review (in press).

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups. Small Group Research, 27, 246–264.

Melé, D. (2003). The challenge of humanistic management. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(1), 77–88.

Melé, D. (2009). Integrating personalism into virtue-based business ethics: The personalist and the common good principles. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 227–244.

Melé, D. (2012a). The firm as a “Community of persons”: A pillar of humanistic business ethos. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 89–101.

Melé, D. (2012b). Management ethics: Placing ethics at the core of good management. Palgrave Macmillan.

Micklethwait, J., & Wooldridge, A. (2009). God is Back. New York: Penguin Press.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Towards a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

Murnighan, J. K., & Conlon, D. J. (1991). The dynamics of intense work groups: A study of British string quartets. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 165–186.

Nash, L. (1994). Believers in business. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Newport, F. (2011). Christianity remains dominant religion in the United States. Gallup. December 23.

Noon, M. (2007). The fatal flaws of diversity and the business case for ethnic minorities. Work, Employment & Society, 21, 773–784.

Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

O’Reilly, C. A., Caldwell, D. F., & Barnett, W. P. (1989). Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 21–37.

Omer, T. C., Sharp, N. Y., & Wang, D. D. (2013). Do local religious norms affect auditors going concern decisions? Working paper.

Oswick, C. (2011). The social construction of diversity, equality and inclusion: An exploration of academic and public discourses. In G. Healy, G. Kirton, & M. Noon (Eds.), Equality, inequalities and diversity: Contemporary challenges and strategies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Page, S. E. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Patee, T., Milner, T., & Welch, M. (1994). Levels of social integration in group contexts and the effects of informal sanction threat on deviance. Criminology, 32, 85–106.

Peccoud, D. (2004). Philosophical and spiritual perspectives on decent work. International Labour Org; illustrated edition.

Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict, and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 1–28.

Perrin, R. D. (2000). Religiosity and honesty: Continuing the search for the consequential dimension. Review of Religious Research, 41(4), 534–544.

Pescosolido, B. (1990). The social context of religious integration and suicide. Sociological Quarterly, 31, 337–357.

Rajan, R., & Wulf, J. (2006). Are perks purely managerial excess? Journal of Financial Economics, 79, 1–33.

Regnerus, M. D. (2003). Moral communities and adolescent delinquency: Religious contexts and community social control. Sociological Quarterly, 44, 523–534.

Regnerus, M. D., Sikkink, D., & Smith, C. (1999). Voting and the Christian right: Contextual and individual patterns of electoral influence. Social Forces, 77, 1375–1401.

Richard, O. C. (2000). Racial diversity, business strategy, and firm performance: A resource-based view. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 164–177.

Richard, O. C., McMillan, A., Chadwick, K., & Dwyer, S. (2003). Employing an innovation strategy in racially diverse workforces: Effects on firm performance. Group and Organization management, 28(1), 107–126.

Roberson, Q. M., & Park, H. J. (2007). Examining the link between diversity and firm performance: The effects of diversity reputation and leader racial diversity. Group and Organization Management, 32(5), 548–568.

Rohrbaugh, J., & Jessor, R. (1975). Religiosity in youth: A personal control against deviant behavior. Journal of Personality, 43, 136–155.

Ross, S. (1973). The economy theory of the agency: The principal’s problem. American Economic Review, 63, 134–139.

Sacco, J. M., & Schmitt, N. (2005). A dynamic multilevel model of demographic diversity and misfit effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 203–231.

Schieman, S. (2011). Education and the importance of religion in decision-making: Do other dimensions of religiousness matter? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(3), 570–587.

Sharfman, M. P. (1996). The construct validity of the Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini social performance ratings data. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(3), 287–296.

Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). God is watching you: Priming god concepts increases prosocial behavior in an anonymous economic game. Psychological Science, 18(9), 803–809.

Shin, A. (2004). Foundations helps Sodexho counter discrimination suit. June 10. Washington Post.

Simons, S. M., & Rowland, K. N. (2011). Diversity and its impact on organizational performance: The influence of diversity constructions on expectations and outcomes. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 6(3), 171–182.

Sloane, D. M., & Potvin, R. H. (1986). Religion and delinquency: Cutting through the maze. Social Forces, 65(1), 87–105.

Smith, T. W., Marsden, P. V., Hout, M., & Kim, J. (2012). General Social Surveys, 1972-2012. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center.

Southern Baptist Convention. (1995). Resolution on racial reconciliation on the 150th anniversary of the southern baptist convention. Accessed May 17, 2013 at http://www.sbc.net/resolutions.

Stack, S., & Kposowa, A. (2006). The effect of religiosity on tax fraud acceptability: A cross-national analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 325–351.

Stainback, K., & Tomaskovic-Devey, D. (2012). Documenting desegregation: Racial and gender segregation in private-sector employment since the civil-rights act. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Stark, R. (1996). Religion as context: Hellfire and delinquency one more time. Sociology and Religion, 57, 163–173.

Stark, R., Doyle, D. P., & Kent, L. (1980). Rediscovering moral communities. In T. Hirschi & M. Gottfredson (Eds.), Understanding crime (pp. 43–52). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Stark, R., Doyle, D. P., & Kent, L. (1982). Religion and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 19, 2–24.

Stulz, R. M., & Williamson, R. (2003). Culture, openness, and finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 70, 313–349.

Thompson, J. M. (2010). Introducing catholic social thought. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Tsui, A. S., Egan, T. D., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1992). Being different: Relational demography and organizational attachment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 549–579.

Valentine, S., & Page, K. (2006). Nine to five: Skepticism of women’s employment and ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(1), 53–61.

Vatican Council II (1965) Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. Accessed at: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vatii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html.

Velasquez, M. (2012). Business ethics: Concepts and cases. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Vitell, S., Bing, M., Davison, H., Ammeter, A., Garner, B., & Novicevic, M. (2009). Religiosity and moral identity: The mediating role of self-control. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(4), 601–613.

Wald, K. D., Owen, D. E., & Hill, S. S. (1988). Churches as political communities. American Political Science Review, 82(2), 531–548.

Walker, G., & Pitts, R. (1998). Naturalistic conceptions of moral maturity. Developmental Psychology, 34, 403–419.

Watson, W. E., Kumar, K., & Michaelsen, L. K. (1993). Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 590–602.

Weaver, G., & Agle, B. (2002). Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 77–98.

Webber, S. S., & Donahue, L. M. (2001). Impact of highly and less job-related diversity on work group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 27, 141–162.

Weber, M. (2009 [1904]) The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism (Norton Critical Editions). (New York: W.W. Norton & Company).

Welch, M., Tittle, C., & Grasmick, H. (2006). Christian religiosity, self-control and social conformity. Social Forces, 84(3), 1605–1623.

Welch, M., Tittle, C., & Patee, T. (1991). Religion and deviance among adult Catholics: A test of the moral communities hypothesis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 159–172.

Wiersema, M. F., & Bird, A. (1993). Organizational demography in Japanese firms: Group heterogeneity, individual dissimilarity, and top management team turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 996–1025.

Wilburn, J. R. (2005). Capitalism beyond the ‘end of history’. In N. Capaldi (Ed.), Business and religion: A clash of civilizations? (pp. 171–181). Salem, MA: M & M Scrivener Press.

Williams, K. Y., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1998). Demography and diversity in organizations: A review of 40 years of research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 20, 77–140.

Winter, G. (2000). Coca-Cola settles racial bias case. The New York Times. November 17, 2000.

Wintoki, M., Linck, J., & Netter, J. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics (forthcoming).

Yermack, D. (2006). Flights of fancy: Corporate jets, CEO perquisites, and inferior shareholder returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 80, 211–242.

Zinbarg, E. (2001). Faith, morals, and money: What the world’s religions tell us about money in the marketplace. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate special issue guest editor, Joan Fontrodona for his excellent guidance, and three anonymous referees for many valuable comments

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Diversity Categories

Appendix: Diversity Categories

Diversity Strengths (DIVERSITY_STRENGTH)

CEO. The company’s chief executive officer is a woman or a member of a minority group.

Promotion. The company has made notable progress in the promotion of women and minorities, particularly to line positions with profit-and-loss responsibilities in the corporation.

Board of Directors. Women, minorities, and/or the disabled hold four seats or more (with no double counting) on the board of directors, or one-third or more of the board seats if the board numbers less than 12.

Work/Life Benefits. The company has outstanding employee benefits or other programs addressing work/life concerns, e.g., childcare, elder care, or flextime. In 2005, KLD renamed this strength from Family Benefits Strength.

Women & Minority Contracting. The company does at least 5 % of its subcontracting, or otherwise has a demonstrably strong record on purchasing or contracting, with women and/or minority-owned businesses.

Employment of the Disabled. The company has implemented innovative hiring programs; other innovative human resource programs for the disabled, or otherwise has a superior reputation as an employer of the disabled.

Other Strength. The company has made a notable commitment to diversity that is not covered by other KLD ratings.

Diversity Concerns (DIVERSITY_CONCERN)

Controversies. The company has either paid substantial fines or civil penalties as a result of affirmative action controversies, or has otherwise been involved in major controversies related to affirmative action issues.

Non-Representation. The company has no women on its board of directors or among its senior line managers.

Other Concern. The company is involved in diversity controversies not covered by other KLD ratings.

Source: KLD Research & Analytics, Inc. The KLD original diversity strength scores also include the Gay & Lesbian Policies: The company has implemented notably progressive policies toward its gay and lesbian employees. In particular, it provides benefits to the domestic partners of its employees. In 1995, KLD added the Gay & Lesbian Policies Strength, which was originally titled the Progressive Gay/Lesbian Policies strength. The problem with this item, however, is that a good number of the Christian denominations do not support policies that benefit gays and lesbians. In fact, several of the Christian denominations have officially taken the position that such policies should be rejected. Consequently, we remove the item of Gay & Lesbian Policies from our measurement of DIVERSITY scores because of continuing controversy.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, J., Jo, H., Na, H. et al. Workforce Diversity and Religiosity. J Bus Ethics 128, 743–767 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1984-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1984-8