Abstract

Taiwan accommodates more than 600 avian species, including about 30 endemic ones. As yet, however, no fossil birds have been scientifically documented from Taiwan, so that the evolutionary origins of this diversified avifauna remain elusive. Here we report on the very first fossil bird from Taiwan. This Pleistocene specimen, a distal end of the left tarsometatarsus, shows diagnostic features of the galliform Phasianidae, including an asymmetric plantar articular facet trochlea metatarsi III. Our discovery of a Pleistocene phasianid from Taiwan opens a new perspective on studies of the evolution of the avifauna in Taiwan because the fossil shows that careful search for fossils in suitable localities has the potential of recovering avian remains. In general, East Asia has an extremely poor avian fossil record, especially if terrestrial birds are concerned, which impedes well-founded evolutionary scenarios concerning the arrival of certain groups in the area. The Phasianidae exhibit a high degree of endemism in Taiwan, and the new fossil presents the first physical evidence for the presence of phasianids on the island, some 400,000–800,000 years ago. The specimen belongs to a species the size of the three larger phasianids occurring in Taiwan today (Syrmaticus mikado, Lophura swinhoii, and Phasianus colchicus). Still, an unambiguous assignment to either of these species is not possible due to the incomplete nature of the left tarsometatarsus. Because the former two species are endemic to Taiwan, the fossil has the potential to yield the first data on their existence in the geological past of Taiwan if future finds allow identification on species-level.

Zusammenfassung

Ein Vertreter der Phasianidae aus dem Pleistozän von Tainan: das erste Vogelfossil aus Taiwan.

Taiwan beherbergt mehr als 600 Vogelarten, von denen etwa 30 endemisch sind. Bisher wurden jedoch keine fossilen Vögel von Taiwan beschrieben, so dass die evolutionären Ursprünge dieser diversifizierten Avifauna im Dunkeln liegen. Hier berichten wir über den allerersten Fossilfund eines Vogels aus Taiwan. Das pleistozäne Fossil ist das distale Ende eines linken Tarsometatarsus, welches diagnostische Merkmale der galliformen Phasianidae aufweist, einschließlich einer asymmetrischen plantaren Gelenkfacette der Trochlea metatarsi III. Unsere Entdeckung eines pleistozänen Vertreters der Phasianidae aus Taiwan eröffnet eine neue Perspektive für Untersuchungen der Evolution der taiwanesischen Avifauna, weil das Fossil zeigt, dass einen gründliche Suche nach Fossilien an geeigneten Orten durchaus das Potenzial hat, Vogelreste zu liefern. Im Allgemeinen ist der Fossilbericht von Vögeln aus Ostasien extrem spärlich, insbesondere was Landvögel betrifft. Das erschwert fundierte Evolutionsszenarien bezüglich der Ankunft von bestimmten Vogelgruppen in der Region. Vertreter der Phasianidae weisen in Taiwan ein hohes Maß an Endemismus auf und das neue Fossil ist der erste direkte Nachweis von Phasianiden auf der Insel vor etwa 400,000–800,000 Jahren. Das Exemplar gehört zu einer Arte von der Größe der drei größeren Phasianiden, die heute in Taiwan vorkommen (Syrmaticus mikado, Lophura swinhoii und Phasianus colchicus). Allerdings ist eine eindeutige Zuordnung zu einer dieser Arten nicht möglich. Weil die beiden ersteren Arten in Taiwan endemisch sind, hat das Fossil das Potenzial, die ersten Daten über ihre Existenz in der geologischen Vergangenheit Taiwans zu liefern, falls zukünftige Funde die Identifizierung auf Artebene ermöglichen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Taiwan accommodates more than 600 species of modern birds [precisely, 674 documented by Lin and Pursner (2020)], including 29 endemic species and 55 endemic subspecies. In terms of its island-scale landmass with such high avian diversity, Taiwan should be an ideal region for studying avian evolution and speciation. Molecular samplings and analyses explored the endemism and evolutionary history of various avian lineages in Taiwan (e.g., Hung et al. 2014; Li et al. 2006). Surprisingly, until now, no avian fossil from Taiwan has been described and documented in the scientific literature. The non-existent fossil record impedes an in-depth integrative understanding of the evolutionary history of this highly diversified insular avifauna.

Here we report on the very first fossil bird from Taiwan (Fig. 1). The specimen represents the distal end of a left tarsometatarsus. Albeit incompletely preserved, the diagnostic morphology of the avian tarsometatarsus allows a taxonomic identification, and the bone shows a close match with phasianids (Galliformes: Phasianidae). Today, seven native species of phasianids (all belonging to different genera: Arborophila, Bambusicola, Coturnix, Lophura, Phasianus, Synoicus, and Syrmaticus) inhabit Taiwan, including four endemic species and one endemic subspecies. The discovery of a phasianid tarsometatarsus from the Middle Pleistocene of Taiwan should encourage more finds to elucidate the evolutionary history of these disparate phasianid lineages in Taiwan.

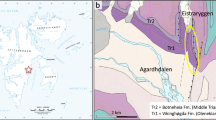

The occurrence of a phasianid left tarsometatarsus from the Pleistocene of Taiwan, NTUM-VP 210117. a geographical map of NTUM-VP 210117; b geological horizon of NTUM-VP 210117; c dorsal view of the left tarsometatarsus, NTUM-VP 210117; d reconstruction of the Pleistocene phasianid based on the extant male Syrmaticus mikado from Taiwan (©Lab of Evolution and Diversity of Fossil Vertebrates, National Taiwan University, illustrated by Cheng-Han Sun)

Institutional abbreviations

NTUM-VP: Vertebrate Paleontology, Museum of Zoology, National Taiwan University, Taiwan; SMF: Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Systematic paleontology

Referred specimen

NTUM-VP 210117, a distal end of the left tarsometatarsus. The high-resolution 3D file of NTUM-VP 210117 can be freely downloaded at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4552928 or https://scholars.lib.ntu.edu.tw/handle/123456789/556266. The specimen was first found by the private collector L.-R. Hou. LRH donated it to CHT (the first and corresponding author), the principal investigator of the Lab of Evolution and Diversity of Fossil Vertebrates at the National Taiwan University for the permanent curation and research.

Locality and geological horizon

NTUM-VP 210117 was collected from the Chi-Ting Formation in the city of Tainan, Taiwan (Fig. 1). The geological age of the Chi-Ting Formation ranges broadly from 0.8 to 0.4 million years ago (Chen 2016) in the Middle Pleistocene; see Chen (2016) and Otsuka (1984) for detailed lithological descriptions and the paleoenvironmental considerations of the Chi-Ting Formation. Due to the long-term, unmanageable, and somewhat destructive fossil collecting behavior along the Tsai-Liao River and nearby areas in Tainan, we refrain from providing the exact locality or more relevant information publicly. Nevertheless, the request can be addressed to CHT.

Diagnosis and morphological remarks

Except for some minor damage due to abrasion, the specimen (NTUM-VP 210117) is relatively intact. The proximal portion is broken, and the preserved proximodistal length is 21.66 mm. Nevertheless, the preserved lateromedial width across trochlea II and IV is 13.81 mm, comparable with male Syrmaticus mikado and Lophura swinhoii (Fig. 2) and slightly larger than that of female Phasianus colchicus (Fig. 2).

Anatomical interpretations of NTUM-VP 210117 from the Pleistocene of Taiwan and morphological comparison to three extant phasianids. a dorsal view of the left tarsometatarsus from the Pleistocene of Taiwan (NTUM-VP 210117); b dorsal view of the left tarsometatarsus of Syrmaticus mikado (SMF 2448); c dorsal view of the left tarsometatarsus of Lophura swinhoii (SMF 19620); d dorsal view of the left tarsometatarsus of Phasianus colchicus (SMF 19325); e plantar view of the left tarsometatarsus from the Pleistocene of Taiwan (NTUM-VP 210117); f plantar view of the left tarsometatarsus of Syrmaticus mikado (SMF 2448); g plantar view of the left tarsometatarsus of Lophura swinhoii (SMF 19620); h plantar view of the left tarsometatarsus of Phasianus colchicus (SMF 19325). The 3D file of NTUM-VP 210117 is freely accessible (see Availability of data and material) for detailed examination of our anatomical explanations

NTUM-VP 210117 can be assigned to the Galliformes because of the possession of a diagnostic feature—a trochlea metatarsi III with an asymmetric plantar articular surface, in which the lateral rim reaches farther proximal than the medial one [Fig. 2; for identifying the diagnostic features, see Mayr (2000)]. In other aspects of its morphology, NTUM-VP 210117 also closely resembles phasianids (Fig. 2), including the presence of a plantar projection on the trochlea metatarsi II, and a relatively narrow incisura intertrochlearis. The specimen belongs to a species the size of the three larger phasianids occurring in Taiwan today: Mikado Pheasant (Syrmaticus mikado), Swinhoe’s Pheasant (Lophura swinhoii), and Common Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), but an unambiguous assignment to either of these species is not possible (Fig. 2). Because the three extant species are almost inseparable based only on the distal portion of the tarsometatarsus, we currently identify NTUM-VP 210117 as Phasianidae gen. et. sp. indet.

Discussion

NTUM-VP 210117 represents the very first avian fossil to have ever been found and documented in Taiwan. Building up the fossil record is extremely time-consuming and requires the input of substantial budgets. However, long-term accumulation or each find reveals previously untold and critical details for deciphering aspects of avian evolution, which molecular studies cannot cover. For example, more than 600 modern avian species inhabit Taiwan (Lin and Pursner 2020), and even whole-genome analyses of the extant species (e.g., Lee et al. 2018) pose limits to our understanding of the origins of each avian lineage and their subsequent evolutionary histories. A full appreciation of their historical biogeography and evolutionary history is impeded by the virtually non-existent avian fossil record in Taiwan, from where literally no avian fossil record has yet been scientifically documented.

Seven native species of phasianid birds occur in Taiwan, including four endemic species (Arborophila crudigularis, Bambusicola sonorivox, Lophura swinhoii, Syrmaticus mikado) and one endemic subspecies (Phasianus colchicus formosanus). This level of endemism is one of the highest among avian families in Taiwan, likely resulting from their ground-living habits and limited flying abilities. A recent paper (Lee et al. 2018) estimated the divergence date of Syrmaticus mikado, a representative phasianid in Taiwan, from other Syrmaticus spp. and concluded that Syrmaticus mikado might have originated or migrated to Taiwan in the Late Pliocene (about 3.47 million years ago). Nevertheless, the inferences based on the molecular clock contribute little to unraveling the evolutionary history, such as the origin, speciation, species longevity, extinction, and turnover. For example, the first species of Syrmaticus arriving in Taiwan almost certainly did not belong to Syrmaticus mikado, but to an ancestral mainland stock of Syrmaticus. The fossil record is the only evidence for revealing the paleoavifaunal composition, extinction events, paleoecological adaptations, and faunal succession. Up to date, two fossil species of Syrmaticus have been described and recognized: Syrmaticus phasianoides from the Late Miocene of Hungary (Jánossy 1991) and Syrmaticus kozlovae from the Miocene/Pliocene boundary of Mongolia (Kurochkin 1985; Zelenkov and Kurochkin 2010). In addition, confirmed fossil material of extant Syrmaticus is likewise poorly documented. Updated morphological analyses with abundant specimens (such as diagnosable coracoid, humerus, and carpometacarpus) substantiated the presence of fossil Syrmaticus in the Middle/Late Pleistocene of Japan (Watanabe et al. 2018), while the other Pleistocene record from China remains dubious (Hou 1993; Shaw 1935). NTUM-VP 210117, though only referable to Phasianidae get. et. sp. indet. based on the distal end of the left tarsometatarsus, promises future finds to reveal the detailed regional colonization, ecological adaptation, and speciation of pheasants along the eastern margin of Eurasia.

Historical legacies (e.g., Tokunaga 1936; Hayasaka 1942) and recent discoveries (e.g., Ito et al. 2018; Tsai and Chang 2019) of vertebrate paleontology in Taiwan demonstrate the potential and its role of contributing to deciphering the evolutionary history in a global frame. Yet, vertebrate paleontology in Taiwan is still in its infancy, mainly owing to the lack of long-term and consistent research effort and public attention. The dinosaur-to-bird transition in the Mesozoic (e.g., Xu et al. 2014) and subsequent radiation of birds in the Cenozoic (Cooney et al. 2017) currently attract much research endeavor. Our discovery of an incomplete phasianid tarsometatarsus from the Pleistocene of Taiwan might seem to be insignificant. However, this ever first documented avian fossil from Taiwan should encourage more finds and pave the way for revealing the origin of the modern avifauna in Taiwan. Similarly, future discoveries may also help to provide critical data on the speciation, extinction, endemism, island biogeography, etc., for avian evolution. For example, modern insular Taiwan and Japan are both geographically separated from the Eurasian landmass. Taiwan is much smaller than Japan in terms of size, but the endemism level of avian diversity in Taiwan is comparable to or even higher (about 30 endemic species: Lin and Pursner 2020) than that of Japan. Fossil collecting and its interpretations, with molecular, ecological, and skeletal studies, should resolve the endemism mystery, whether it results from differential speciation or extinction rate, or regional niche partitioning. In addition, our first discovery of the delicate avian fossil from Taiwan suggests the prospects of finding similar fragile fossil bats (Chiroptera) that represent the other main component of vertebrate diversity in the Cenozoic sky, apart from birds. Future paleontological fieldwork and in-depth research should reveal the origin and evolution of flying vertebrates (birds and bats) from Taiwan, laying the foundation for understanding the biodiversity origin and interchange along the eastern margin of Eurasia.

Availability of data and materials

The original fossil, NTUM-VP 210117, is curated at the Lab of Evolution and Diversity of Fossil Vertebrates (part of the Museum of Zoology, National Taiwan University). Besides, the high-resolution 3D file of NTUM-VP 210117 is digitally stored and freely downloadable at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4552928 or https://scholars.lib.ntu.edu.tw/handle/123456789/556266.

References

Chen WS (2016) Geological introduction of Taiwan. Geological Society of Taiwan.

Cooney CR, Bright JA, Capp EJR, Chira AM, Hughes EC, Moody CJA, Nouri LO, Varley ZK, Thomas GH (2017) Mega-evolutionary dynamics of the adaptive radiation of birds. Nature 542:344–347. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21074

Hayasaka I (1942) On the occurrence of mammalian remains in Taiwan: a preliminary summary. Taiwan Chigaku Kizi 13:95–109

Horsfield T (1821) Systematic arrangement and description of birds from the island of Java. Trans Linn Soc Lond 13:133–200

Hou L (1993) Avian fossils of Pleistocene from Zhoukoudian. Memoirs of Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology. Academia Sinica 19:165–297

Hung CM, Hung HY, Yeh CF, Fu YQ, Chen D, Lei F, Yao CT, Yao CJ, Yang XJ, Lai YT (2014) Species delimitation in the Chinese bamboo partridge Bambusicola thoracica (Phasianidae; Aves). Zool Scr 43:562–575

Ito A, Aoki R, Hirayama R, Yoshida M, Kon H, Endo H (2018) The rediscovery and taxonomical reexamination of the longirostrine crocodylian from the Pleistocene of Taiwan. Paleontol Res 22:150–155. https://doi.org/10.2517/2017pr016

Jánossy D (1991) Late Miocene bird remains from Polgárdi (W-Hungary). Aquila 98:13–35

Kurochkin E (1985) Birds of the central Asia in Pliocene. Academy of Science of the USSR.

Lee CY, Hsieh PH, Chiang LM, Chattopadhyay A, Li KY, Lee YF, Lu TP, Lai LC, Lin EC, Lee H (2018) Whole-genome de novo sequencing reveals unique genes that contributed to the adaptive evolution of the Mikado pheasant. GigaScience 7:giy044

Li SH, Li JW, Han LX, Yao CT, Shi H, Lei FM, Yen C (2006) Species delimitation in the Hwamei Garrulax canorus. Ibis 148:698–706

Lin DL, Pursner S (2020) State of Taiwan’s Birds. Endemic Species Research Institute, Taiwan Wild Bird Federation, Taipei

Linnaeus C (1758) Systema naturae: Stockholm Laurentii Salvii.

Mayr G (2000) A new basal galliform bird from the Middle Eocene of Messel (Hessen, Germany). Senckenb Lethaea 80:45–57

Otsuka H (1984) Stratigraphic position of the Chochen vertebrate fauna of the T’ouk’oushan Group in the environs of the Chochen district, southwest Taiwan, with special reference to its geologic age. J Taiwan Museum 37:37–55

Shaw TH (1935) Preliminary observations on the fossil birds from Chou-Kou-Tien. Bull Geol Soc China 14:77–82

Temminck C (1820) Manuel d’ornithologie, vol 1. Gabriel Dufour, Paris

Tokunaga S (1936) Discovery of fossil crocodile in Japan. J Geol Soc Jpn 43:432

Tsai CH, Chang CH (2019) A right whale (Mysticeti, Balaenidae) from the Pleistocene of Taiwan. Zool Lett 5:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-40019-40153-z

Watanabe J, Matsuoka H, Hasegawa Y (2018) Pleistocene non-passeriform landbirds from Shiriya, northeast Japan. Acta Palaeontol Pol 63:469–491. https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00509.2018

Xu X, Zhou Z, Dudley R, Mackem S, Chuong CM, Erickson GM, Varricchio DJ (2014) An integrative approach to understanding bird origins. Science 346:1253293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1253293

Zelenkov N, Kurochkin E (2010) Neogene phasianids (Aves: Phasianidae) of Central Asia: 3. Genera Lophogallus gen. nov. and Syrmaticus. Paleontol J 44:328–336

Acknowledgements

We thank Li-Ren Hou for collecting and donating the fossil material (now known as NTUM-VP 210117) to CHT; I-Lin Lu and his 3D company for producing the 3D document of NTUM-VP 210117; Cheng-Han Sun for illustrating the Pleistocene phasianid based on extant male Syrmaticus from Taiwan and helping to prepare the figures.

Funding

CHT was financially supported by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 108-2621-B-002-006-MY3) and the public donations to the Lab of Evolution and Diversity of Fossil Vertebrates, National Taiwan University (NTU FD107028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHT conceived and designed the research. CHT and GM collected and analysed the data. Both authors discussed, wrote, and reviewed the drafts of the paper, and approved the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Consent for publication

Both authors approved the contents and agreed with the submission for publication.

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, CH., Mayr, G. A phasianid bird from the Pleistocene of Tainan: the very first avian fossil from Taiwan. J Ornithol 162, 919–923 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-021-01886-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-021-01886-w