Abstract

Background

The phase 3 VELIA trial evaluated veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel and as maintenance in patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

Methods

Patients with previously untreated stage III–IV high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma were randomized 1:1:1 to control (placebo with carboplatin/paclitaxel and placebo maintenance), veliparib-combination-only (veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel and placebo maintenance), or veliparib-throughout (veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel and veliparib maintenance). Randomization stratification factors included geographic region (Japan versus North America or rest of the world). Primary end point was investigator-assessed median progression-free survival. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics were evaluated in a subgroup of Japanese patients.

Results

Seventy-eight Japanese patients were randomized to control (n = 23), veliparib-combination-only (n = 30), and veliparib-throughout (n = 25) arms. In the Japanese subgroup, median progression-free survival for veliparib-throughout versus control was 27.4 and 19.1 months (hazard ratio, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.18–1.16; p = 0.1 [not significant]). In the veliparib-throughout arm, grade 3/4 leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia rates were higher for Japanese (32%/88%/32%) versus non-Japanese (17%/56%/28%) patients. Grade 3/4 anemia rates were higher in non-Japanese (65%) versus Japanese (48%) patients. Early introduction of olanzapine during veliparib monotherapy maintenance phase may help prevent premature discontinuation of veliparib, via its potent antiemetic efficacy.

Conclusions

Median progression-free survival was numerically longer in Japanese patients in the veliparib-throughout versus control arm, consistent with results in the overall study population. Pharmacokinetics were comparable between Japanese and non-Japanese patients. Data for the subgroup of Japanese patients were not powered to show statistical significance but to guide further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is diagnosed in an estimated 314,000 women worldwide annually accounting for approximately 207,000 deaths [1]. In Japan alone, there were an estimated 13,400 cases in 2020, and an estimated 4,700 deaths [2]. More than 70% of ovarian cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage and nearly all ovarian tumors are epithelial in origin [3].

High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma is the most common subtype of epithelial ovarian cancer. It is associated with a high frequency of inherited mutations; approximately 50% of tumors have genomic alterations causing deficiencies in homologous recombination repair [4]. The majority of these are in the breast cancer susceptibility genes (BRCA)1 (55%) or BRCA2 (19%) [5, 6], and ethnic-specific BRCA variations have been identified in Asian countries [7]. Tumor cells harboring such mutations are highly sensitive to DNA-damaging agents, such as platinum-based chemotherapy, and to poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [8,9,10,11,12].

In the past two decades, the standard-of-care first-line treatment for patients with advanced ovarian cancer has been a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Despite initial positive clinical responses to this treatment, many patients develop resistance after the first or subsequent treatment cycles, with up to 70% reporting disease recurrence [13]. Consequently, patients with advanced ovarian cancer have a poor prognosis, indicating a clear unmet medical need for novel therapeutic strategies to improve survival.

PARP inhibitors, such as olaparib, rucaparib, and niraparib, have proven effective as single agents in treating patients with recurrent ovarian cancer and as maintenance therapy in patients who responded to platinum-based therapy [11, 14,15,16,17,18]. The combination of PARP inhibitors and chemotherapy has been challenging, due to hematologic toxicities leading to necessary dose reductions of both agents [19].

Veliparib (formerly ABT-888) is a potent, highly selective oral PARP-1 and -2 inhibitor shown to enhance the activity of DNA-damaging chemotherapy, including platinum agents [20]. Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials in patients with ovarian cancer have demonstrated antitumor activity and tolerability of veliparib both as a single agent and combined with platinum-based chemotherapy [21,22,23]. Veliparib also has an overall manageable safety profile in Japanese patients [24,25,26].

The phase 1 study confirming tolerability of veliparib monotherapy in Japanese patients reported nausea and vomiting in almost all patients (93.8% each), resulting in veliparib dose interruption, reduction, or discontinuation in most patients [26]. Therefore, intensive antiemetic use was encouraged during the veliparib monotherapy phase in the VELIA/GOG-3005 trial (NCT02470585), a randomized, international phase 3 trial evaluating veliparib combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel and continued as maintenance in patients with untreated stage III or IV high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. In the intention-to-treat population, veliparib combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel and continued as maintenance therapy significantly prolonged progression-free survival (23.5 months) compared with carboplatin/paclitaxel alone (17.3 months) (HR, 0.68; 95% CI 0.56–0.83; P < 0.001) [27]. Herein, we report safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic analyses from Japan subgroup in the VELIA/GOG-3005 study.

Patients and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, regulations governing clinical study conduct, and ethical principles with their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board. All patients provided written informed consent before any study procedures were performed.

Patients

Patient eligibility criteria for this study have been published previously [27]. Briefly, this study enrolled women ≥ 18 years of age with previously untreated, histologically diagnosed International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III or IV high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status between 0 and 2.

Study design and treatments

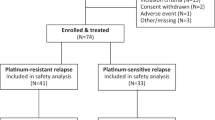

The study design is described in Fig. 1. Although frozen tumor sections could be used to provisionally diagnose high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma to proceed with blood draws for germline (g)BRCA analysis if written consent was obtained, definitive diagnosis using permanent formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor specimens was required to be eligible for the study. Region of Japan was a stratification factor; other stratification factors have been published previously [27]. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to one of three study arms: control (placebo with carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy followed by placebo maintenance), veliparib-combination-only (veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy followed by placebo maintenance), or veliparib-throughout (veliparib with carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy followed by veliparib maintenance). During the combination therapy phase, patients received oral veliparib (150 mg) or matching placebo twice daily combined with intravenous carboplatin (area under the curve 6 mg/mL/minute every 3 weeks) and paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 weekly or 175 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) for six 21-day cycles (cycles 1–6). After completion of the combination therapy phase, patients who did not progress per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST) received oral veliparib (300 mg twice daily, increasing to 400 mg twice daily if tolerated) or matching placebo for an additional thirty 21-day cycles (cycles 7–36) during the maintenance therapy phase.

VELIA study design. aAdded as stratification factor ~ 14 months after trial initiation, due to noted imbalance. AUC area under the curve, BID twice daily, CNS central nervous system, combo combination, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FIGO International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, gBRCA clinically significant germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, HGSC high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, JPN Japan, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, Q every, R randomization, RECIST Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, W weeks

The primary objective of this study was to compare investigator-assessed progression-free survival for the veliparib-throughout arm versus control arm. As this was the primary objective of the study, data from the veliparib-throughout and control arms are included in this report. Secondary objectives included assessing safety. Pharmacokinetic parameters of veliparib were also evaluated.

Assessments

Postbaseline tumor assessments were collected at the following intervals: every 9 weeks, the end of the combination phase, every subsequent 12 weeks up to 2 years followed by every 6 months up to 3 years, then annually until disease progression. Plasma samples for pharmacokinetic analyses were collected on day 1 of cycles 1–4.

Treatment-emergent adverse events are defined as adverse events occurring between first dose of veliparib/placebo until 30 days after the last dose. Adverse events were summarized using preferred terms within a System Organ Class according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat population, defined as all randomized patients. Patients who received at least one dose of study drug were included in safety analyses. This manuscript presents data from Japanese patients in the control and veliparib-throughout study arms, because the comparison between these two arms was the primary objective of the overall trial. The cutoff date for data presented in this manuscript was May 3, 2019.

Progression-free survival was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methodology, and progression-free survival was compared between the control and veliparib-throughout treatment arms using the log-rank test. Unless otherwise noted, statistical significance was determined by a one-sided P value ≤ 0.025. In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, we will provide our data for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if such is requested.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

In total, 1140 patients were randomized (control, n = 375; veliparib-combination-only, n = 383; or veliparib-throughout, n = 382). Seventy-eight Japanese patients from 24 institutions in Japan were randomized and received treatment (control, n = 23; veliparib-combination-only, n = 30; or veliparib-throughout, n = 25). Demographics and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1. Compared with non-Japanese patients, a higher proportion of Japanese patients were < 65 years of age, received interval surgery, had ECOG status 0, received every-3-weeks paclitaxel, had any macroscopic disease after primary surgery, and had homologous recombination-deficient tumors.

Concordance between frozen tumor sections and permanent formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens

Fifty-six patients underwent blood draws for gBRCA analysis using intraoperative histopathologic diagnosis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, and a definitive diagnosis was available for 55 patients. Of these patients, 52 were diagnosed as high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (concordance rate: 95%) using permanent formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. Forty-eight patients were eligible and randomized; the remaining four patients were not enrolled due to reasons other than discordance of histopathologic diagnosis.

Efficacy

At the data cutoff for the primary efficacy analysis, progression-free survival in Japan subgroup was longer for the veliparib-throughout arm compared with the control arm (Fig. 2) [27]. In Japan subgroup, median progression-free survival was 27.4 months in the veliparib-throughout arm compared with 19.1 months in the control arm (HR, 0.46; 95% CI 0.18–1.16; P = 0.1 [not significant]). This was comparable with the overall study intention-to-treat population, in which median progression-free survival was 23.5 months in the veliparib-throughout arm compared with 17.3 months in the control arm (HR, 0.68; 95% CI 0.56–0.83; P < 0.001) [27].

Copyright © 2022 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society

Investigator-assessed progression-free survival in the veliparib-throughout and control groups for Japanese patients and overall study population. Distributions were estimated using Kaplan–Meier methodology in the intention-to-treat populations of Japanese patients (a) and the overall study population (b). Both graphs present results from the veliparib-throughout arm compared with the control arm (primary end point). Progression-free survival was compared between the control and veliparib-throughout treatment arms using the stratified log-rank test. The dashed line indicates the median, and tick marks indicate censored data. CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, PFS progression-free survival, VEL veliparib. b From New England Journal of Medicine, Coleman, R.L., Fleming, G.F., Brady, M.F., Swisher, E.M., Steffensen, K.D., Friedlander, M., Okamoto, A., Moore, K.N., Efrat Ben-Baruch, N., Werner, T.L., Cloven, N.G., Oaknin, A., DiSilvestro, P.A., Morgan, M.A., Nam, J.H., Leath III, C.A., Nicum, S., Hagemann, A.R., Littell, R.D., Cella, D., Baron-Hay, S., Garcia-Donas, J., Mizuno, M., Bell-McGuinn, K., Sullivan, D.M., Bach, B.A., Bhattacharya, S., Ratajczak, C.K., Ansell, P.J., Dinh, M.H., Aghajanian, C., Bookman, M.A., Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer, 381, 2403–2415.

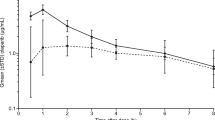

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma concentrations of veliparib in Japanese and non-Japanese patients are shown in Fig. 3. Veliparib pharmacokinetics were comparable between Japanese and non-Japanese patients at the beginning of these cycles, including patients in both the veliparib-combination-only and veliparib-throughout study arms.

Pharmacokinetics of veliparib in Japanese patients. Veliparib concentrations were measured in plasma samples from Japanese and non-Japanese patients taken on day 1 of treatment for cycles 1–4. Patients in both the veliparib-combination-only and veliparib-throughout arms were included in analyses. C cycle, D day

Safety profile

In both Japanese and non-Japanese subgroups, the median number of cycles of placebo/veliparib received was higher in the control arm compared with the veliparib-throughout arm (Japan, 25 [range, 7–36] versus 17 [2–36]; non-Japan, 18 [1–36] versus 15 [1–36]). The median number of cycles of carboplatin was six for both arms in both subgroups (Japan, range of 6–6 and 4–6 for control and veliparib-throughout, respectively; non-Japan, range of 1–6 for both arms), and the median number of cycles of paclitaxel was six for both arms in both subgroups (Japan, range of 6–6 and 4–6 for control and veliparib-throughout, respectively; non-Japan, range of 1–6 and 1–7, respectively).

An overview of treatment-emergent adverse events is presented in Table 2. The most common adverse events in the veliparib-throughout arm for both Japan and non-Japan subgroups were nausea (100% and 79%) and neutropenia (100% and 74%). In both subgroups, adverse events of nausea were predominantly of grade 1/2 and the most common grade 3/4 adverse events were hematologic.

Common any grade adverse events with ≥ 10% higher rate in the veliparib-throughout versus control arm were nausea and thrombocytopenia (Japan and non-Japan subgroups), and anemia and vomiting (non-Japan subgroup only). Rates of alopecia and of peripheral sensory neuropathy were ≥ 10% higher in the control arm versus the veliparib-throughout arm in Japan subgroup only.

In the veliparib-throughout arm, rates of any grade alopecia, nausea, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia were > 10% higher in the Japanese subgroup compared with non-Japanese subgroup. Rates of grade 3/4 leukopenia and neutropenia were > 10% higher in the veliparib-throughout arm in the Japanese subgroup compared with the non-Japanese subgroup. Conversely, rates of any grade and grade 3/4 anemia were > 10% higher in the veliparib-throughout arm in the non-Japanese subgroup compared with the Japanese subgroup.

The rate of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to veliparib discontinuation were comparable for patients in the veliparib-throughout arm in the Japanese (n = 5, 20%) and the non-Japanese (n = 92, 26%) subgroups. Nausea most frequently led to discontinuation among patients in the Japanese subgroup in the veliparib-throughout arm (n = 4, 16%). The rate of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to veliparib dose interruption and/or reduction was comparable for the veliparib-throughout arm in the Japanese (n = 17, 68%) and the non-Japanese (n = 259, 74%) subgroups. The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events leading to veliparib interruption/reduction (≥ 20% of patients) for patients receiving veliparib-throughout in the Japanese subgroup were nausea (n = 7, 28%), neutropenia (n = 6, 24%), and thrombocytopenia (n = 5, 20%).

Rates of gastrointestinal and hematologic adverse events of special interest by treatment phase are described in Table 3. Anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea occurred at higher frequencies during combination therapy compared with maintenance in both the Japanese and the non-Japanese subgroups for patients receiving veliparib-throughout. Vomiting occurred at similar frequencies between phases in the non-Japanese subgroup and at a higher frequency during the maintenance phase (n = 10, 45%) than the combination therapy phase (n = 8, 32%) in the Japanese subgroup.

For nausea and/or vomiting, antiemetics were used to prevent premature discontinuation of veliparib or to maintain quality of life. At the time of the interim database lock, metoclopramide (68%), olanzapine (56%), prochlorperazine (44%), and granisetron (40%) were frequently administered during veliparib monotherapy maintenance phase for Japanese patients in the veliparib-throughout arm (Table 4). In this arm, 15 (60%) patients received antiemetics on the day of initiation of veliparib maintenance therapy. Four patients prematurely discontinued veliparib due to nausea. Interestingly, all four patients received metoclopramide (single agent: n = 2, combination with prochlorperazine or granisetron: n = 2). None of the six patients receiving olanzapine on the first day of veliparib maintenance therapy prematurely discontinued veliparib due to nausea and/or vomiting.

There were no treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death in either treatment arm in the Japanese subgroup. In the non-Japanese subgroup, eight patients (2.3%) in the veliparib-throughout arm and six patients (1.7%) in the control arm had a treatment-emergent adverse event leading to death; none were considered related to veliparib/placebo by the investigator.

Discussion

In the subgroup analysis presented here, Japanese patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma who received veliparib combined with platinum-based chemotherapy and continued as maintenance experienced numerically longer progression-free survival compared with Japanese patients who received platinum-based chemotherapy alone. This was consistent with the previously published primary analysis of this trial [27]. It is noteworthy that subgroup analysis of Japanese patients was performed to guide further investigation, as it was not powered to show statistical significance.

As gBRCA status was required for randomization, it was a significant problem for patients to await initiation of chemotherapy for approximately 2 weeks until gBRCA results were available. Provisional pathologic diagnosis using frozen tumor sections takes only several hours from biopsy to diagnosis, with a high concordance rate between rapid and definitive diagnoses [28, 29]. Rapid diagnosis for gBRCA blood sampling allows definitive diagnosis and gBRCA testing to be performed in parallel, enabling earlier initiation of study treatment.

The most common adverse events observed in Japanese and non-Japanese patients in the veliparib-throughout arm were nausea (100% and 79%, respectively) and neutropenia (100% and 74%), and these adverse events occurred at greater frequencies than in the respective control arms (nausea: 74% and 67%, neutropenia: 91% and 66%). The toxicity profile observed in the veliparib-throughout arm for the Japanese subgroup is comparable with that observed in small phase 1 studies of veliparib as a single agent or combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel in patients with ovarian cancer or other solid tumors [25, 26]. The toxicity profile for the veliparib-throughout arm was generally consistent between the Japanese and non-Japanese subgroups, although frequency of some common adverse events differed between the two subgroups. Specifically, higher rates of alopecia, nausea, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia were observed in the Japanese subgroup and higher rates of anemia were observed in the non-Japanese subgroup. Utilization of the weekly paclitaxel regimen was more common in non-Japanese (53.3%) than Japanese (31.3%) subgroups in the VELIA study. In the JGOG 3016 study, anemia was more commonly observed for the weekly paclitaxel regimen (69%) than the tri-weekly regimen (44%), with P value < 0.0001 [30]. Differences in the utilization of the weekly paclitaxel regimen might be one of the reasons that explains lower incidence of anemia for the Japanese subgroup.

Although pharmacokinetic drug profiles are known to differ among patients of different ethnicities [31], the results of this study demonstrate similar veliparib plasma levels in Japanese patients compared with non-Japanese patients. Notably, this is despite the lower median weight of Japanese patients compared with non-Japanese patients in both the control and veliparib-throughout arms. The similar profiles between subgroups observed here are in line with previous studies [24, 26, 32, 33]. A prior study has also shown no significant pharmacokinetic interaction between veliparib and carboplatin or paclitaxel in Japanese patients [25].

With the comparable veliparib pharmacokinetic profiles in Japanese and non-Japanese patients, the reason for observed differences in frequency of some adverse events between the populations is unclear. Different polymorphisms between populations may lead to differential sensitivity to drug. In a previously reported study, it was hypothesized that the differences in allelic distribution in genes involved in paclitaxel metabolism or DNA repair between Japanese and Western populations may result in differential sensitivity to paclitaxel. However, no significant associations were identified between adverse event frequency and the polymorphisms explored [34]. In the current study, the prevalence of BRCA mutations is numerically higher among Japanese vs non-Japanese subgroups. Some reports have indicated increased hematologic toxicity in BRCA mutation carriers; however, a recently reported subanalysis of the VELIA trial showed that gBRCA status did not impact safety in this study [35]. Additional research into the mechanism underlying the observed differences is needed.

The present study assesses the efficacy and safety of PARP inhibitor therapy during combination chemotherapy and continued as maintenance in patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer. Other studies in newly diagnosed patients have generally evaluated PARP inhibitors as maintenance therapy after combination chemotherapy only [18, 36, 37]. Patients enrolled in the current study represent a broad population of patients with advanced high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma who were not required to have a prior response to first-line chemotherapy.

Although the analysis of progression-free survival in Japan subgroup was prespecified, it was not powered for statistical significance and is limited by the relatively small number of patients. While baseline demographic and disease characteristics were generally balanced between treatment arms within the larger non-Japanese subgroup, there were some imbalances within the Japanese subgroup.

Conclusions drawn on differences in rates of specific adverse event rates between Japanese and non-Japanese subgroups are limited by the relatively small number of patients in the Japanese subgroup. Despite the small numbers in the Japanese subgroup, there are consistencies between the observations in this study and in other previous reports. For example, the higher rate of neutropenia observed in the Japanese subgroup vs the non-Japanese subgroup is consistent with a previous report indicating higher rates of grade 3/4 neutropenia for Japanese vs American patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel [34].

Although nausea was common, it was predominantly low-grade. Nausea was also reported less frequently during the maintenance phase than the combination phase in both Japanese (maintenance: n = 14, 64%; combination: n = 21, 84%) and non-Japanese (maintenance: n = 158, 55%; combination: n = 223, 63%) subgroups in the veliparib-throughout arm. PARP inhibitors including olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib are categorized as moderate to high emetic risk [38]. With such oral anticancer agents, anticipatory nausea and vomiting are quite problematic for patients and may impede their ability to continue taking medication. In these situations, patients sometimes discontinue medication with or without consulting a treating physician. In a phase 1 study of single-agent veliparib in Japanese patients, some patients were treated with olanzapine several days (or weeks) after developing veliparib-induced nausea; however, it was not well-controlled. The NCCN guidelines for antiemesis state that “prevention is key” for anticipatory emesis. Therefore, prophylactic or early antiemetic use including olanzapine was encouraged for Japanese investigators. As seen in Table 4, metoclopramide was the most commonly used antiemetic. However, in previous literature, olanzapine was significantly better than metoclopramide in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy [39]. Considering these data there are two important points in controlling veliparib-induced nausea and vomiting: 1) early introduction of antiemetics for preventing the initial episode of nausea and/or vomiting, and 2) use of stronger antiemetics such as olanzapine. Although data are limited, early introduction of olanzapine may be effective in controlling veliparib-induced nausea. Optimal strategies for managing nausea and vomiting during treatment warrant further investigation.

Conclusions

Veliparib combined with chemotherapy followed by veliparib maintenance therapy provided numerically longer progression-free survival compared with chemotherapy alone, with a generally manageable safety profile in Japanese patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. These data support the efficacy and safety of veliparib combined with platinum-based chemotherapy and continued as maintenance in this population at the dose administered to the global population.

Availability of data and materials

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization (2020) GLOBOCAN 2020: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/25-Ovary-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed Mar 2022

Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research (2021) Cancer statistics in Japan – 2021. https://ganjoho.jp/public/qa_links/report/statistics/pdf/cancer_statistics_2021.pdf. Accessed Mar 2022

Jelovac D, Armstrong DK (2011) Recent progress in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 61:183–203

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2011) Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474:609–615

Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK et al (2011) Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:18032–18037

Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI et al (2014) Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 20:764–775

Bhaskaran SP, Huang T, Rajendran BK et al (2021) Ethnic-specific BRCA1/2 variation within Asia population: evidence from over 78,000 cancer and 40,000 non-cancer cases of Indian, Chinese, Korean and Japanese populations. J Med Genet 58:752–759

Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD et al (2005) Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434:913–917

Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ et al (2005) Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434:917–921

Mukhopadhyay A, Plummer ER, Elattar A et al (2012) Clinicopathological features of homologous recombination-deficient epithelial ovarian cancers: sensitivity to PARP inhibitors, platinum, and survival. Cancer Res 72:5675–5682

Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C et al (2012) Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 366:1382–1392

Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK et al (2015) Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 33:244–250

Matsumoto K, Onda T, Yaegashi N (2015) Pharmacotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer: current status and future perspectives. Jpn J Clin Oncol 45:408–410

Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C et al (2014) Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:852–861

Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F et al (2017) Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1274–1284

Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J et al (2016) Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 375:2154–2164

Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D et al (2017) Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390:1949–1961

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G et al (2018) Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 379:2495–2505

Oza AM, Cibula D, Oaknin Benzaquen A et al (2015) Olaparib combined with chemotherapy for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 16:87–97

Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y et al (2007) ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res 13:2728–2737

Coleman RL, Sill MW, Bell-McGuinn K et al (2015) A phase II evaluation of the potent, highly selective PARP inhibitor veliparib in the treatment of persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer in patients who carry a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation - an NRG oncology/gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol 137:386–391

Steffensen KD, Adimi P, Jakobsen A (2017) Veliparib monotherapy to patients with BRCA germ line mutation and platinum-resistant or partially platinum-sensitive relapse of epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase I/II study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 27:1842–1849

Moore KN, Miller A, Bell-McGuinn KM et al (2020) A phase I study of intravenous or intraperitoneal platinum based chemotherapy in combination with veliparib and bevacizumab in newly diagnosed ovarian, primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancer. Gynecol Oncol 156:13–22

Mizugaki H, Yamamoto N, Nokihara H et al (2015) A phase 1 study evaluating the pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of veliparib (ABT-888) in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel in Japanese subjects with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 76:1063–1072

Nishio S, Takekuma M, Takeuchi S et al (2017) Phase 1 study of veliparib with carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel in Japanese patients with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci 108:2213–2220

Nishikawa T, Matsumoto K, Tamura K et al (2017) Phase 1 dose-escalation study of single-agent veliparib in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Sci 108:1834–1842

Coleman RL, Fleming GF, Brady MF et al (2019) Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2403–2415

Wang KG, Chen TC, Wang TY et al (1998) Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis in gynecology. Gynecol Oncol 70:105–110

Boriboonhirunsarn D, Sermboon A (2004) Accuracy of frozen section in the diagnosis of malignant ovarian tumor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 30:394–399

Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F et al (2009) Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374:1331–1338

Malinowski HJ, Westelinck A, Sato J et al (2008) Same drug, different dosing: differences in dosing for drugs approved in the United States, Europe, and Japan. J Clin Pharmacol 48:900–908

Mostafa NM, Chiu YL, Rosen LS et al (2014) A phase 1 study to evaluate effect of food on veliparib pharmacokinetics and relative bioavailability in subjects with solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 74:583–591

Munasinghe W, Stodtmann S, Tolcher A et al (2016) Effect of veliparib (ABT-888) on cardiac repolarization in patients with advanced solid tumors: a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 78:1003–1011

Gandara DR, Kawaguchi T, Crowley J et al (2009) Japanese-US common-arm analysis of paclitaxel plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a model for assessing population-related pharmacogenomics. J Clin Oncol 27:3540–3546

Aghajanian C, Swisher EM, Okamoto A et al (2022) Impact of veliparib, paclitaxel dosing regimen, and germline BRCA status on the primary treatment of serous ovarian cancer – an ancillary data analysis of the VELIA trial. Gynecol Oncol 164:278–287

Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S et al (2019) Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2416–2428

González-Martin A, Pothuri B, Vergote I et al (2019) Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 381:2391–2402

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2022) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Antiemesis. Version 2.2002. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf. Accessed Aug 2022

Navari RM, Nagy CK, Gray SE (2013) The use of olanzapine versus metoclopramide for the treatment of breakthrough chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 21:1655–1663

Acknowledgements

Results of this study were partially presented at the Japanese Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) Annual Meeting, Sendai, Japan, January 29–30, 2021. AbbVie and the authors thank all the trial investigators and the patients who participated in this clinical trial, as well as support for patient recruitment via patient referral service of the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. Medical writing support was provided by Thayer Darling, PhD, of Aptitude Health, and funded by AbbVie.

Funding

AbbVie funded this study and participated in the study design, research, analysis, data collection, interpretation of data, reviewing, and approval of the manuscript. All authors had access to relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this manuscript. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship. All authors agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: RLC, AO, and YN. Provision of patients and collection of data: MM, KI, HN, HK, SK, KU, SN, HT, MO, MT, HT, SN, DA, RLC, TE, and AO. Assembly of data: YN, CKR, HH, and HX. Data analysis: YN and HX. Data interpretation: all authors. Reviewing/editing the manuscript: all authors. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.M.: research grants (AbbVie, MSD, Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca). K.I.: speakers’ bureau (AstraZeneca); research grants (AbbVie Inc, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical). H.N.: research grants (AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Takeda Pharmaceutical). H.K.: research grants (AbbVie); donations (Chugai Pharmaceutical). S.K.: manuscript fees and other (Kinpodo, Johnson & Johnson); research grants (AbbVie GK, Merck, Genmab, Clovis, AstraZeneca, Zeria Pharmaceutical). K.U.: research grants (AbbVie, Chugai, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, MSD, Tsumura Pharmaceuticals); speakers’ bureau (Chugai, AstraZeneca, Kyowa Kirin, Bayer, Tsumura Pharmaceuticals, MSD). Sh.Na.: speakers’ bureau (Chugai Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Asahi Kasei Medical, Terumo Corporation); research grants (AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical). Hi.Ta.: research grants (AbbVie). M.O.: research grants (AbbVie). M.T.: research grants (AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD). Hi.To.: Research grants (AbbVie). Sa.Na.: Speakers’ bureau (Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca); research grants (AbbVie, Ono Pharmaceutical). D.A.: speakers’ bureau (AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Myriad Genetics, Takeda Pharmaceutical); consultancy (AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Myriad Genetics, Takeda Pharmaceutical); research grants (AbbVie, Takeda Pharmaceutical). R.L.C.: research grants (Merck, AstraZeneca, Roche, AbbVie, Esperance, Clovis, Gateway, V Foundation); scientific steering committee (AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Clovis, GamaMabs, Genmab, ImmunoGen, Janssen, Merck, Roche/Genentech, GSK, Gradalis). Y.N., C.R., H.H., and H.X.: employees of AbbVie and may hold stock or stock options. N.K.: research grants (AbbVie). T.E.: speakers’ bureau (AstraZeneca, MSD, Chugai). A.O.: speakers’ bureau (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., Zeria Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., Eisai Co., Ltd., Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bayer Holding Ltd., ASKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Fuji Pharma Co., Ltd.); research grants (Meiji Holdings Co., Ltd., Fuji Pharma Co., Ltd., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd., ASKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mizuno, M., Ito, K., Nakai, H. et al. Veliparib with frontline chemotherapy and as maintenance in Japanese women with ovarian cancer: a subanalysis of efficacy, safety, and antiemetic use in the phase 3 VELIA trial. Int J Clin Oncol 28, 163–174 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-022-02258-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-022-02258-x