Abstract

The continuously growing global demands on a finite land resource will require better strategic policies and management of trade-offs to avoid conflicts between different land-use sectors. Visions of the future can support strategic planning by stimulating dialogue, building a consensus on shared priorities and providing long-term targets. We present a novel approach to elicit stakeholder visions of future desired land use, which was applied with a broad range of experts to develop cross-sectoral visions in Europe. The approach is based on (i) combination of software tools and facilitation techniques to stimulate engagement and creativity; (ii) methodical selection of stakeholders; (iii) use of land attributes to deconstruct the multifaceted sectoral visions into land-use changes that can be clustered into few cross-sectoral visions, and (iv) a rigorous iterative process. Three cross-sectoral visions of sustainable land use in Europe in 2040 emerged from applying the approach in participatory workshops involving experts in nature conservation, recreation, agriculture, forestry, settlements, energy, and water. The three visions—Best Land in Europe, Regional Connected and Local Multifunctional—shared a wish to achieve a land use that is sustainable through multifunctionality, resource use efficiency, controlled urban growth, rural renewal and widespread nature. However, they differ on the scale at which land services are provided—EU-wide, regional or local—reflecting the land-sparing versus land-sharing debate. We discuss the usefulness of the approach, as well as the challenges posed and solutions offered by the visions to support strategic land-use planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world has changed rapidly in the last decades, with profound modifications in the ways we use land to support a growing (United Nations 2015) and increasingly wealthy (Wiedmann et al. 2015) and urban population (Cumming et al. 2014). The successful transition towards a global society that can live within the planet’s ecological boundaries is widely seen as the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced (Ellis 2011; Rockstrom et al. 2009; Steffen et al. 2015). More people and changing lifestyle will require more space and more food, timber, clean water and energy, which will have to be provided by a finite land resource, facing added pressures from changing climate (Lambin and Meyfroidt 2011). In this context, land multifunctionality, where the same area of land can offer many environmental, social, cultural and economic benefits at the same time, can play a crucial role (Pérez-Soba et al. 2008).

Future land-use change is uncertain as it is determined by complex interactions between the biophysical environment and human activity, which in turn are shaped by historical and contemporary cultural and socio-economic processes (Jepsen et al. 2015). Managing its change sustainably is a major challenge (Guerry et al. 2015), and responsibility will need to be shared by governments, the private sector and individual citizens, as emphasised in the new UN Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations 2015). The needed fundamental ‘sustainability transitions’ require a dialogue that engages actors across society and will depend on experimentation, learning and sharing ideas (EEA 2016).

Scenario analysis is a technique that takes into account the complex land-use interactions in a structured manner (van der Heijden 2005), and therefore, it is often used in assessments of future land-use change (Helming et al. 2011; Verburg et al. 2008) for strategic planning. These assessments frequently relied on business-as-usual scenarios inspired by past trends and processes of change, or on explorative scenarios describing how the future may unfold. Visions (or normative scenarios) represent another scenario technique, which is particularly strong in ensuring saliency and, if developed in a participatory approach, in ensuring legitimacy (Rounsevell and Metzger 2010). Visions of a desired future can stimulate dialogue, help build a consensus on shared priorities and support planning by providing long-term targets (Howlett 2007; Koomen et al. 2011). Visions describe a pre-specified picture of the world achievable only through certain actions, where the scenario itself becomes an argument for taking those actions (Ogilvy, 1992). As such, developing visions could represent a major step towards achieving a desired future land use through a better understanding what type of world society would like to live in (Buijs et al. 2006, Shipley and Michela 2006).

However, the translation of scenario narratives into strategic targets remains challenging. To be useful for decision-making, any type of scenario needs to strike a balance between credibility, legitimacy and relevance (Volkery et al. 2008; Pérez-Soba and Maas 2015). Using participatory approaches involving sufficiently large groups of stakeholders, and adequate time for the elicitation process and for review and outreach, can enhance credibility, legitimacy and saliency and thereby promote their uptake in land-use policies and strategies (Swart et al. 2004). In addition, innovative participatory techniques and computer-based tools can help to stimulate the imagination and enhance stakeholders’ engagement (Appleton and Lovett 2003; Vervoort et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2016). Imagining a distant future is a difficult exercise for human beings (Bryant and Veroff 2007), because the brain recombines past experience information to imagine the future (Grant and Suddendorf 2005). A distant future implies a big mental gap from everyday experiences, particularly when we need to extrapolate existing trends into a future without historic precedent.

In an effort to build a roadmap towards sustainable land resource management in Europe (Pedroli et al. 2015), explorative and normative land-use scenarios were linked in a unique approach. Land-use scenarios were modelled (Lotze-Campen et al. 2017), and the projections were linked to stakeholder visions of desired future land use (this study) by identifying the pathways reaching the visions (Verkerk et al. 2016). A crowd-sourcing exercise to explore young citizens’ ideas and desires on their life in 2040 complemented the vision elicitation process (Metzger et al. 2017).

This paper describes the methodological approach that was developed to elicit cross-sectoral visions, its implementation in a series of participatory workshops involving a broad range of stakeholders on nature conservation, recreation, agriculture, forestry, settlements, energy and water. It depicts as well the three cross-sectoral visions derived from the workshops and analyses the visions’ shared wishes and differences, which largely reflect the land-sparing versus land-sharing debate. Finally, we discuss the usefulness of the approach for supporting strategic land-use planning, as well as the challenges posed and solutions offered by the visions to support transitions towards sustainable land use.

Methodological approach for eliciting cross-sectoral visions of land use in Europe

The methodological approach to elicit cross-sectoral visions with stakeholders embraces a process involving the workshop design and development of various methods and tools that are applied in the workshops. The process has two consecutive steps. The first step involves the development of visions in sectoral workshops. Although the resulting visions include a societal perspective, we call them ‘sectoral’, as they are intrinsically linked to the sectors represented in the workshops. The second step involves the integration of the sectoral visions into cross-sectoral visions, which comprises the deconstruction of the visions and their unification and consolidation in feedback stakeholder workshops. The stepwise approach is depicted in Fig. 1. The workshop design and the methods and tools used in the approach are detailed in the next sections.

Design of the workshops to elicit sectoral visions

The overall objective of the sectoral workshops was to elicit visions for desired future European land use from a broad range of relevant stakeholders. When designing the workshops, we anticipated contrasting visions and wanted to encourage experts to think ‘out of the box’ and openly about their wishes. Workshops were designed to support this challenging creative process, whilst also providing comparable information on which to base our subsequent analysis.

The workshops were structured around four sectoral groupings associated with major European land uses: nature conservation and recreation; food, bioenergy and timber production; settlements and transport infrastructure and energy and water. This coverage of land uses ensured a broad basis to build cross-sectoral visions. Despite the sectoral focus, stakeholders were invited to participate as individuals and with the explicit aim to think about broader cross-sectoral (societal) land-use visions. The Chatham House Rule (https://www.chathamhouse.org/about/chatham-house-rule) was used to encourage openness and the sharing of information. The design should allow the stakeholders to feel engaged, contribute and have a rewarding individual experience, i.e. the process should not just ‘take’, but also ‘give back’. The workshops would last two full days, a realistic estimation of the time we could ask stakeholders to commit voluntarily and adequate time for the elicitation process. The 2 days allowed a progressive development of visions. The first day started with individual reflections about stakeholders’ (land use related) preferences on their life in 2040, followed by taking a perspective from stakeholders’ sector on three aspects of land use in 2040: demand of products, land-use change and impacts and culminating in broader integrative visions considering societal aspects as lifestyle and global impacts. The workshop structure with the sessions and material produced is presented in Table 1.

Stakeholder selection

The stakeholders, all professionals representing the main land-use sectors, were carefully selected following Gramberger et al. (2014) method to ensure a plurality of views that would limit outcome biases and improve the process legitimacy. Selection features were defined, using land-use sector as main feature to group stakeholders in the four sectoral workshops. Additional selection features included geographical origin (Northern, Western, Central/Eastern or Southern Europe); age (< 30-year-old, 30–50-year-old or >50-year-old), which was considered an important aspect, given that perspectives on the future may be heavily influenced by generational aspects (Metzger et al. 2017); gender; professional sector (business and economy, government and policy making, research, civil society, practitioners and NGO) and spatial level (European, national, regional or local). A fit for purpose database was built considering the selection features and populated with the help of the project partners. Minimum quotas were set for each feature to ensure a balanced representation and transparency in the selection of participants. For example, we aimed to have 15–20 stakeholders participating in each workshop to allow a good balance between personal attention and the chance to be individually heard. Up to 20 individual stakeholders per workshop were therefore identified that matched the quotas. A minimum gender balance of 30% female and 30% male participants was seen as important for the legitimacy and inclusiveness of the exercise. These stakeholders were invited individually and 69 finally attended the workshops. Stakeholders would attend the workshop without prior knowledge or preparation and with varying degrees of experience in foresight.

Software tools used for building the visions

To enhance out-of-the-box thinking, support discussion and capture the creative process, two computer-based tools were developed. We called them ‘canvas tools’ as they enable participants to fill a blank space with elements of their vision, both in images and text (Fig. 2). They were designed to improve the vision development process. Firstly, interactive and visually attractive computer-based tools are engaging and may stimulate participants to imagine the future in a creative, vivid and detailed manner. The technique brings out also implicit ideas, supports structuring them and reveals inconsistencies and gaps (Vervoort et al. 2010; Bhowmick 2006). The tools can support discussion between participants by diminishing language barriers, sharing of results and function as external memory during the 2-day sessions. The individual canvas was designed as graphic novel describing one’s future life in four pages—home, work, food and free time. More details on the features of the individual canvas can be found in Metzger et al. (2017), as they served as basis for the crowd-sourcing exercise to explore young citizens’ ideas and desires on their life in 2040. Four sectoral canvases were designed containing questions and images tailored to the sectoral themes. Each sectoral canvas had two pages: the first dealing with the expected demand of goods or services provided by the sector and the second with impacts of these demands on land use. Each page had a menu on the left side presenting pictures grouped in themes (including land use, agricultural products, modes of transport, environmental pressures); a central area showing an empty space intended for positioning the selected pictures, adding text and showing linkages visualising the group’s visions and a list of topics on the right side including relevant issues/drivers (socio-economic change, climate change, technological development, etc.) (see Fig. 3).

Use of land attributes

Whilst insightful on their own, creating cross-sectoral land-use visions formed part of a larger effort to develop a roadmap towards sustainable land resource management in Europe (Pedroli et al. 2015). The visioning process therefore had to consider a number of land-use aspects to enable linking the visions with model-based explorative scenarios of land use (Verkerk et al. 2016), without compromising the creative thinking process. These land-use aspects were included in the canvas tools and a range of exercises combining verbal and written descriptions with images, maps, graphs indicating trends and system diagrams explaining relationships between key aspects (e.g. land uses and drivers of change). They were also used to deconstruct and cluster the sectoral visions (see the “Clustering and consolidation of 15 sectoral visions into 3 shared visions across land-use sectors” section 3.2).

Elicitation of cross-sectoral visions

Sectoral workshops

Four sectoral workshops were held in June (18–19 and 21–22) and September (24–25 and 27–28) 2012, attracting 15–19 stakeholders per workshop. Online Resource 1 provides a detailed characterisation of stakeholders for each workshop. During the 2-day workshops, the stakeholders participated in several sessions following the workshop design presented in the “Design of the workshops to elicit sectoral visions” section.

The first phase focused on eliciting stakeholders individual desires of their everyday lives in 2040 (individual visions), as transition towards the sectoral visions. They used the canvas of individual visions and selected images that represented their lives in 2040 (see example in Fig. 2). In the second phase, stakeholders worked in self-selected groups of like-minded individuals, formed around short statements about future land use for their sector. These groups shared ideas in discussions and exercises supported by different tools (canvas of sectoral visions, maps of Europe, pictures with landscapes and whiteboards). One facilitator that moderated the discussion and operated the sectoral canvas tool assisted each group. The 15 resulting sectoral visions for 2040 were then discussed in plenary. In the final phase, the same groups of participants supported by the facilitator expanded the context of their sectoral visions to the wider society. They explicitly discussed other land uses, as well as global impacts of European land use and lifestyles by using images, drawing, photos and text. The resulting broader sectoral visions were presented in plenary during a ‘grand expo’.

Clustering and consolidation of 15 sectoral visions into 3 shared visions across land-use sectors

In order to be meaningful for strategic land-use planning, the 15 sectoral visions had to be integrated into a smaller, consistent set of visions across land-use sectors. To allow clustering, the 15 sectoral visions were deconstructed using land-use types and land-use attributes as their building blocks. This was done by a team of researchers participating in the workshops, who consistently completed extensive spreadsheet tables for each of the 15 sectoral visions (included in Online Resource 2) using the material collected in the workshops (see Table 1). The researchers determined for each cell whether the vision expressed a future change (i.e. increase, decrease, no change) compared to the present. They also noted a level of confidence in their interpretation (high, medium, low) and detailed where evidence was found in the workshop materials for the sake of transparency.

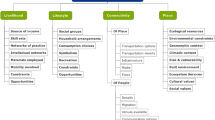

The land-use types considered in the matrix were built-up areas (separately for cities, towns and villages), agriculture (separately for food, fuel, fibre and fodder), forestry (separately for timber harvesting as main measure, and multifunctional forests), nature conservation, transport (separately for public and private transport), other infrastructure (wind mills, pylons, etc.) and water.

The land-use attributes included land cover extent (i.e. the area covered by a land cover type), land-use management (i.e. the intensity by which land is managed), land-use pattern (i.e. the spatial configuration of different land uses), land-use services (i.e. the benefits provided to society by land use), global land impacts (i.e. indirect effects of land use in Europe on land use outside Europe) and lifestyle (i.e. behaviour of people that affects land use). Whilst climate change is crucial for land use, it was considered to have limited impact on land use by 2040 and therefore not included in the process to develop cross-sectoral visions.

The researchers worked with a subset of 20 stakeholders from the original group to elicit a limited set of cross-sectoral visions using as material the former tables. They were selected to allow a good balance between the four sectoral workshop participants and the chance to contribute individually to the targeted discussions. In an iterative process, over two feedback workshops (December 2013 and April 2014), stakeholders and researchers clustered the 15 sectoral visions and unified them into a set of three shared visions across land-use sectors, by unlocking the commonalities in desired transitions (increase, decrease, no change) of key land-use attributes (extent of agriculture, forest and urban areas, food and forest production, degree of nature conservation, rural viability and green infrastructure). The key land-use attributes were selected based on two criteria: characterising main land uses and their services to enable presence of all sectors in the cross-sectoral visions and allowing the link of qualitative statements made by stakeholders with quantitative modelling results (Verkerk et al. 2016). The final result was presented and agreed with the stakeholders.

Description of the resulting visions of future desired land use

Sectoral visions

The 15 sectoral visions were each summarised in the form of a narrative (included in Online Resource 3) based on the analysis of the spreadsheets (see former section on Clustering and consolidation of 15 visions). The names and short descriptions of the visions are presented in Table 2. These visions offer multifaceted, multi-sectoral, multiscale descriptions of sustainable futures in 2040, with a sectoral focus. Despite differences in their underlying concepts and ultimate aspirations, the 15 visions clearly share a common wish of multifunctionality, efficient use of land resources, controlled urban growth, enhanced liveability of rural areas and nature as the ever-present foundation ensuring an optimal delivery of public goods and ecosystem services. They differ, however, in the scale on which they envision multifunctionality, which ranges from the whole EU territory to the local level.

Cross-sectoral visions

The three shared visions across land-use sectors are named Best Land in Europe, Regional Connected and Local Multifunctional to symbolise the main differences in the spatial scale. The visions are outlined in Table 3. On the largest, continental scale, the most appropriate land is matched to the best use, with specialisation as a key principle (Best Land in Europe). At the intermediate, regional scale, the matching is between the people in the region and their resources, with energy and transport connectivity as a fundamental premise (Regional Connected). And on the smallest, local scale, the highly diverse needs of Europeans are mainly met locally by using knowledge of local conditions to achieve better use of land and the supply of goods and services on the spot (Local Multifunctionality).

An overview of the main differences among the three visions is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

Benefits and weaknesses of the methodological approach

Developing cross-sectoral land-use visions at EU scale is still rather unique, and few examples can be found in literature (Volkery et al. 2008; Kok et al. 2015). Most of the studies are at local or regional scales and do not cover all land-use sectors (Faysse et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2016). Compared to these previous exercises, our approach covers all Europe and is cross-sectoral. It involves a broad coverage of stakeholders from many regions in Europe, which represent the main land-use sectors and bring a rich diversity of cultural contexts. Instead of bringing all experts together in a workshop, as previous studies do, our approach grouped experts in separated sectoral workshops, which makes it easier to develop a consistent set of “sectoral” visions. Many of the participatory scenario exercises found in literature (Volkery et al. 2008; Brown and Castellazzi 2014; Wang et al. 2016) have used a range of methods and visualisation tools separately, but we combined and adapted them in an iterative process to get a greater co-creation and richness in the visions. The use of electronic canvas as visualisation tool facilitates the linking of qualitative stakeholder statements with quantitative model simulations and at the same time enhances the engagement and understanding of the modelling outcomes by stakeholders. Finally, our approach enables the development of plausible policy pathways to reach the visions (Verkerk et al. 2016).

The approach developed was particularly successful to engage stakeholders, to stimulate their creativity, enhance dialogue among the land-use sectors represented and to help build a common ground of shared priorities. This ‘open’ process was appreciated by stakeholders, but that implied that it was more difficult to reach an end reconciling their views into few cross-sectoral visions that would be recognised as their own. In fact, several attempts were made by the research team to cluster the 15 visions by using statistical methods and re-grouping them into the four SRES axes (Nakicenovic et al. 2000) until a new clustering method was developed which was found transparent by the stakeholders. It took also substantial time to align the qualitative stakeholder’s statements (changes in key land-use attributes) with the quantitative model outcomes, as previously found by Volkery et al. (2008). All these complications indicate how important it is planning ample time for the elicitation process.

The approach ensured credibility, legitimacy and saliency of the visions. Involving the same group of stakeholders in the full elicitation process enhanced their trust in the vision framing. All this led to shared visions and enhanced their credibility, as the belief in a scenario is much limited to the people involved in their construction (Schoonenboom 2003). Furthermore, the methodical and broad selection of stakeholders helped to enhance not only the legitimacy of the visions among potential users, but also their salience by giving ample room to address sectoral special concerns and therefore convince that results are relevant to support decision-making processes (EEA 2001).

The combination of different facilitation techniques with the use of computer-based tools (the canvas) contributed to stakeholder’s openness, engagement and increased their creativity, as it was evaluated at the end of the workshops. Unwillingness of some stakeholders to reveal their values and stakes can create tensions between participants and prevent creative thinking (Tonn 2003). We used the individual canvases to overcome this issue and to helping the stakeholders in the difficult task to imagine the future at the start of the sectoral workshops. This canvas tool also helped to reveal personal views and beliefs regarding land use-related issues of work, travel, food and free time, which otherwise would have become obscured in the group process. The use of the sectoral canvas in groups helped to understand each other’s ideas and discussing openly complex issues related to land use. In conclusion, the canvases proved to be a helpful tool to elicit stakeholder visions in a workshop setting.

Land-use attributes played a crucial role in the elicitation process and improved the understanding of the complex modelling. They helped to analyse and deconstruct the 15 rich sectoral visions into simple statements, which facilitated the vision clustering and unification into the three shared cross-sectoral visions. In addition, they enabled to link the qualitative stakeholder statements (visions) with quantitative land-use projections in the roadmap construction; this ensured that important aspects of land use would be addressed in both the visioning process and the land-use modelling. However, stakeholders included elements in their visions that could not be addressed by land-use models, whilst the land-use models could also provide insights in land use not considered by stakeholders when defining their visions (Verkerk et al. 2016). Finally, stakeholders became acquainted with the land-use attributes during the vision elicitation process, and this helped them—who are usually wary of ‘black box’ models—to better understand the modelled outcomes reaching (or not) ‘their’ desired land-use futures; the visions building and the modelling were loosely linked to avoid that stakeholders would be hampered in their creative thinking.

Policy and societal implications of the cross-sectoral visions

The cross-sectoral visions pose important challenges in terms of the policy, strategies and governance; technological developments and changes in lifestyle needed to achieve them. However, they also offer solutions, as we discussed below for each of the visions.

Best Land in Europe would supply the largest quantity of goods and services at continental scale by most efficient use of land resources but would probably result in a polarisation of the urban-rural differences, and some remote areas would struggle to keep their population unless land use and economic activities are restructured. Some productive forest and agricultural land located in less suitable areas would be taken out of conventional use. This would lead to land sparing (Fischer et al. 2014), with sustainable intensification of agriculture and forestry. For agriculture, this would occur on the landscapes best suited to supporting production functions—access to water, fertile soils and proximity to market—but abandonment of more extensive primary production systems in less favoured areas. For forestry, this vision implied that forest production would shift from the south of Europe to less drought-prone areas in the north. This vision would require political collaboration between the EU Member States (e.g. to decide on the best location for land use and land functions across scales), at national level (e.g. financial incentives supporting management of abandoned land or re-structuring in remote rural areas) and regional level (e.g. plans to reverse urban sprawl and encourage compact city development). It would also require investment in connectivity and mobility across Europe. Society would need to embrace the re-structuring of Europe’s landscapes to obtain maximum efficiency from the land, and this may sometimes conflict with cultural identity issues.

Regional Connected moves away from specialisation to achieve regional self-sufficiency across multiple services. This implies intensifying agricultural and forestry production across European regions. This vision would require a strong regional government and a stable governance structure that promotes collaboration between regions. Whilst stronger regulatory and incentive-based regional policy would be needed to minimise land-use conflicts, there would be a need to regulate trade between regions and internationally. This vision also would require large public and private investments in technology, infrastructure and social cohesion to increase the connectivity within the region and investments in the EU energy grid to be self-sufficient. The societal challenges mainly refer to the need to embrace major lifestyle changes, such as regional food consumption, compact urban living, shift to public transport and willingness to pay the cost of these changes.

The vision for the smallest scale is Local Multifunctionality, which implies a land-sharing (Fischer et al. 2014) approach with the highest diversification of land use. This vision aims at increasing self-sufficiency and avoiding negative relocation of land-use activities overseas, which would lead to a carbon-neutral economy. The challenges are multiple and would require a capable, local decision-making and a radical shift in behaviour and a bottom-up governance. On the technological side, the vision would imply large investments in new, smart technologies, such as district heating, urban agriculture and EU energy grid. Society would need to embrace major lifestyle changes and would need to reconsider consumption patterns (diet, seasonal food, waste reduction). Society would need to be willing and able to pay for the cost of this local self-sufficiency, e.g. producing food locally may be more expensive under sub-optimal conditions. Altogether, this vision seems the most challenging vision to achieve without a radical transformation in society and decision-making processes, underpinned by individual behavioural change. This was confirmed by the absence of the considered policy options that would represent pathways to achieve this vision (Verkerk et al. 2016). Nevertheless, this turned to be the most desired vision by the young generation of Europeans in the crowd-sourcing exercise (Metzger et al. 2017).

Conclusions

We present an innovative methodological approach to elicit visions of land use that increases the body of knowledge about what sustainable land use could look like in Europe in the next decades. The vision elicitation process, with its methods and tools, links and combines effectively the desires of stakeholders from a broad range of sectoral and disciplinary perspectives resulting in rich and robust narratives. These narratives highlight the stakeholder’s strong desire for multifunctional land systems, identifying the potential synergies and trade-offs between main land-use sectors and the challenges ahead. Achieving the cross-sectoral visions and their goals will crucially depend on paradigmatic changes in national and regional governance, policy strategies, technological developments and changes in lifestyle, in particular those related to urban systems and their links to nature, food and timber, energy, water and transport. The outcomes advance understanding of plausible pathways in the transition towards a sustainable land use in Europe. The next step will be to operationalize these visions into strategic plans by engaging and working close with the appropriate organisations in innovation projects at regional and local level. Most importantly, realise that the land-use transitions implied by these cross-sectoral visions require great efforts to reinforce the societal behaviours and create a culture of long-term thinking.

References

Appleton K, Lovett A (2003) GIS-based visualisation of rural landscapes: defining ‘sufficient’ realism for environmental decision-making. Landscape Urban Plann 65:117–131 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00245-1

Bhowmick T (2006) Building an exploratory visual analysis tool for qualitative researchers. Proc AutoCarto, Vancouver, WA 10(1):1.66.503

Brown I, Castellazzi M (2014) Changes in climate variability with reference to land quality and agriculture in Scotland. Int J Biometeorol 59(6):717–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-014-0882-9

Bryant FB, Veroff J (2007) Savoring: a new model of positive experience. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Buijs AE, Pedroli B, Luginbühl Y (2006) From hiking through farmland to farming in a leisure landscape: changing social perceptions of the European landscape. Landsc Ecol 21(3):375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-005-5223-2

Cumming GS, Buerkert A, Hoffmann EM, Schlecht E, Von Cramon-Taubadel S, Tscharntke T (2014) Implications of agricultural transitions and urbanization for ecosystem services. Nature 515(7525):50–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13945

EEA (2001) Designing effective assessments: the role of participation, science and governance, and focus. Experts corner by Noelle Eckley, Environmental issue report No.26, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen ISBN: 92–9167–404-4

EEA (2016) Sustainability transitions: now for the long term. Eionet report | No 1/2016, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen doi:https://doi.org/10.2800/096291

Ellis EC (2011) Anthropogenic transformation of the terrestrial biosphere. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 369(1938):1010–1035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0331

Faysse N, Rinaudo JD, Bento S, Richard-Ferroudji A, Errahj M, Varanda M, Imache A, Dionnet M, Rollin D, Garin P, Kuper M, Maton L, Montginoul M (2014) Participatory analysis for adaptation to climate change in Mediterranean agricultural systems: possible choices in process design. Reg Environ Chang 14(S1):S57–S70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0362-x

Fischer J, Abson DJ, Butsic V, Chappell MJ, Ekroos J, Hanspach J, Kuemmerle T, Smith HG, von Wehrden H (2014) Land sparing versus land sharing: moving forward. Con Lett 7(3):149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12084

Gramberger M, Zellmer K, Kok K, Metzger MJ (2014) Stakeholder integrated research (STIR): a new approach tested in climate change adaptation research. Clim Chang 128(3-4):201–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1225-x

Grant JB, Suddendorf (2005) Recalling yesterday and predicting tomorrow. Cogn Dev 20(3):362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2005.05.002

Guerry AD, Polasky S, Lubchenco J, Chaplin-Kramer R, Daily GC, Griffin R, Ruckelshaus M, Bateman IJ, Duraiappah A, Elmqvist T, Feldman MW, Folke C, Hoekstra J, Kareiva PM, Keeler BL, Li S, McKenzie E, Ouyang Z, Reyers B, Ricketts TH, Rockström J, Tallis H, Vira B (2015) Natural capital and ecosystem services informing decisions: from promise to practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(24):7348–7355. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503751112

Helming K, Diehl K, Kuhlman T, Jansson T, Verburg PH, Bakker M, Pérez-Soba M, Jonese L, Verkerk PJ, Tabbush P, Morris J, Drillet Z, Farrington J, Le Mouël P, Zagame P, Stuczynskik T, Siebieleck G, Wiggering H (2011) Ex-ante impact assessment of policies effecting land use—B: application of the analytical framework. Ecol Soc 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03840-160129

Howlett M (2007) Analyzing multi-actor, multi-round public policy decision-making processes in government: findings from five Canadian cases. Can J Polit Sci 40:659–684 doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423907070746, 03

Jepsen MR, Kuemmerle T, Müller D, Erb K, Verburg PH, Haberl H, Vesterager JP, Andrič M, Antrop M, Austrheim G, Björn I, Bondeau A, Bürgi M, Bryson J, Caspar G, Cassar LF, Conrad E, Chromý P, Daugirdas V, Van Eetvelde V, Elena-Rosselló R, Gimmi U, Izakovicova Z, Jančák V, Jansson U, Kladnik D, Kozak J, Konkoly-Gyuró E, Krausmann F, Mander Ü, McDonagh J, Pärn J, Niedertscheider M, Nikodemus O, Ostapowicz K, Pérez-Soba M, Pinto-Correia T, Ribokas G, Rounsevell M, Schistou D, Schmit C, Terkenli TS, Tretvik AM, Trzepacz P, Vadineanu A, Walz A, Zhllima E, Reenberg A (2015) Transitions in European land-management regimes between 1800 and 2010. Land Use Policy 49:53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.07.003

Kok K, Bärlund I, Flörke M, Holman I, Gramberger M, Sendzimir J, Stuch B, Zellmer K (2015) European participatory scenario development: strengthening the link between stories and models. Clim Chang 128(3-4):187–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1143-y

Koomen E, Koekoek A, Dijk E (2011) Simulating land-use change in a regional planning context. Appli Spat Anal Policy 4(4):223–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-010-9053-5

Lambin EF, Meyfroidt P (2011) Global land use change, economic globalization, and the looming land scarcity. PNAS 108:3465–3472. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100480108

Lotze-Campen, H, Verburg, PH, Popp, A, Lindner, M, Verkerk, PJ, Moiseyev, A, Schrammeijer, E, Helming, J, Tabeau, A, Schulp, CJE, van der Zanden, EH, Lavalle, C, Silva, FB, Walz, A, Bodirsky, B (2017) A cross-scale impact assessment of European nature protection policies under contrasting future socio-economic pathways. Reg Environ Chang 1–12 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1167-8

Metzger MJ, Murray-Rust D, Houtkamp J, Jensen, A, La Riviere, I, Paterson, JS, Pérez-Soba, M, Valluri-Nitsch, C (2017) How do Europeans want to live in 2040? Citizen visions and their consequences for European land use. Reg Environ Chang doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1091-3

Nakicenovic N, Alcamo J, Davis G, de Vries B, Fenhann J, Gaffin S, Gregory K, Grübler A, Jung TY, Kram T, La Rovere EL, Michaelis L, Mori S, Morita T, Pepper W, Pitcher H, Price L, Raihi K, Roehrl A, Rogner HH, Sankovski A, Schlesinger M, Shukla P, Smith S, Swart R, Van Rooijen S, Victor N, Dadi Z (2000) Special report on emissions scenarios. Working group III, intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC), Cambridge University Press

Ogilvy J (1992) Future studies and the human sciences: the case for normative scenarios. Futur Res Q 8(2): 5–65

Pedroli B, Rounsevell M, Metzger M, Paterson J, and the VOLANTE consortium (2015) The VOLANTE roadmap towards sustainable land resource management in Europe. VOLANTE final project document, Alterra Wageningen UR, p 24 ISBN 978-94-6257-407-6

Pérez-Soba M, Petit S, Jones L, Bertrand N, Briquel V, Omodei-Zorini L, Contini C, Helming K, Farrington JH, Tinacci Mossello M, Wascher D, Kienast F, De Groot R (2008) Land use functions : a multifunctionality approach to assess the impact of land use changes on land use sustainability. Helming K, Pérez-Soba M, Tabbush P (Eds) Sustainability impact assessment of land use changes: 375-404; Berlin (Springer) doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-78648-1_19

Pérez-Soba M, Maas R (2015) Scenarios: tools for coping with complexity and future uncertainty? . In: Jordan AJ, Turnpenny JR (eds) The tools of policy formulation. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK. http://www.elgaronline.com/view/9781783477036.xml, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783477043.00014

Rockstrom J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson A, Chapin FS, Lambin E, Lenton T, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber H, Nykvist B, de Wit CA, Hughes T, van der Leeuw S, Rodhe H, Sorlin S, Snyder P, Costanza R, Svedin U, Falkenmark M, Karlberg L, Corell RW, Fabry V, Hansen J, Walker B, Liverman D, Richardson K, Crutzen P, Foley J (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461(7263):472–475. https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a

Rounsevell MDA, Metzger MJ (2010) Developing qualitative scenario storylines for environmental change assessment. Wil Inter Rev. Clim Change 1:606–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.63

Schoonenboom J (2003) Toekomstscenarios en beleid, tijdschrift voor Belied Politiek en Maatschappij 30:212–217, 4, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1347/benm.30.4.212.25076

Shipley R, Michela JL (2006) Can vision motivate planning action? Plann Prac Res 21(2):223–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450600944715

Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockström J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, De Vries W, De Wit CA, Folke C, Gerten D, Heinke J, Mace GM, Persson LM, Ramanathan V, Reyers B, Sörlin S (2015) Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347 doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855, 6223, 1259855

Swart R, Raskin P, Robinson J (2004) The problem of the future: sustainability science and scenario analysis. Glob Environm Change-Human Policy Dimens 14(2):137–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.002

Tonn JC (2003) Mary P. Follett: creating democracy, transforming management. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, DOI: https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300096217.001.0001

United Nations (2015) World population prospects: the 2015 revision, key findings and advance tables. New York. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.241

Van der Heijden K (2005) Scenarios : the art of strategic conversation. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, UK ISBN 0-470–02368-6

Verburg P, Eickhout B, van Meijl H (2008) A multi-scale, multi-model approach for analyzing the future dynamics of European land use. Ann Reg Sci 42:57–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-007-0136-4

Verkerk PJ, Lindner M, Pérez-Soba M, Paterson JS, Helming J, Verburg PH, Kuemmerle T, Lotze-Campen H, Moiseyev A, Müller D, Popp A, Schulp CJE, Stürck J, Tabeau A, Wolfslehner B, van der Zanden EH (2016) Identifying pathways to visions of future land use in Europe. Reg Env Change DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1055-7

Vervoort JM, Kok K, van Lammeren R, Veldkamp T (2010) Stepping into futures: exploring the potential of interactive media for participatory scenarios on social-ecological systems. Futures 42(6):604–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.031

Volkery A, Ribeiro T, Henrichs T, Hoogeveen Y (2008) Your vision or my mode? Lessons from participatory land use scenario development on a European scale. Syst Pract Action Res 21:459–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-008-9104-x

Wang C, Miller D, Brown I, Jiang Y, Castellazzi M (2016) Visualisation techniques to support public interpretation of future climate change and land-use choices: a case study from N-E Scotland. Int J Digital Earth, 9:6, 586–605 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2015.1111949

Wiedmann TO, Schandl H, Lenzen M, Moran D, Suh S, West J, Kanemoto K (2015) The material footprint of nations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(20):6271–6276. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1220362110

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded through the EU 7th framework projects VOLANTE (project number 265104) and is part of the strategic research program KBIV “Sustainable spatial development of ecosystems, landscapes, seas and regions”, funded by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, and carried out by Wageningen Environmental Research. The authors would like to thank the 69 stakeholders who inspired these visions, the professional workshop facilitation team from Prospex bvba for their valuable support and all the partners of the VOLANTE project for their comments on the eliciting visions approach.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Soba, M., Paterson, J., Metzger, M.J. et al. Sketching sustainable land use in Europe by 2040: a multi-stakeholder participatory approach to elicit cross-sectoral visions. Reg Environ Change 18, 775–787 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1297-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1297-7