Abstract

In this paper we present an evolutionary heuristic for the offline two-dimensional variable-sized bin packing problem. In this problem we have to pack a set of rectangles into two-dimensional variable-sized rectangular bins. The bins are divided into types, and the bins in different types have different sizes and possibly different weights (costs). There are (sufficiently) many bins from each type, and any rectangle fits into at least one bin-type. The goal is to pack the rectangles into the bins without overlap, parallel to the sides, so that the total area of the used bins (or total cost) is minimized. Our algorithm is a hybrid heuristic. It uses two different techniques to generate the descendants: either estimation of distribution algorithm and sampling the resulting probability model, or applying the usual operators of evolutionary algorithms (selection, mutation). To pack the rectangles into the bins the algorithm uses the strategy of randomly choosing one of two placement heuristics, that pack always only one group (one to three) of rectangles. It improves the quality of the solutions with three local search procedures. The algorithm has been tested on benchmark instances from the literature and has been compared with other heuristics and metaheuristics. Our algorithm outperformed the previously published results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The offline two-dimensional variable-sized bin packing problem (2DVSBPP) can be defined as follows: given a set of n rectangles (items or elements) \(R\, = \,\left\{ {r_{1} ,r_{2} , \ldots ,r_{n} } \right\}\). The widths and the heights of the rectangles are denoted by wi, and \(h_{i} (i\, = \,1,2, \ldots ,n)\), respectively. There are also given m different types of rectangular bins with sizes Wj, and Hj, resp., and Cj cost belongs to the bin type \(j \, (j\, = \,1,2, \ldots ,m)\). The items must be packed without overlapping into bins with sides parallel to the appropriate sides of the bins. No rotation is allowed. The aim is to pack the items into bins with minimum total cost. Usually, costs are the areas of the bins, but generally, it can happen that the costs are independent of the areas of the bins. We will consider the case of minimal areas of bins.

Since the variable-sized bin packing problem is a generalization of the NP-hard classical bin packing problem, it is also NP-hard (see Garey and Johnson 1979; Friesen and Langston 1986). Therefore different algorithms have been developed to give approximation solutions. These algorithms can be classified into heuristics and metaheuristics. Metaheuristics usually based on evolutionary algorithm (EA) (Haouari and Serairi 2009), variable neighbourhood search (VNS) (Blum et al. 2010), and GRASP methods (Alvarez-Valdes et al. 2012). In the last decade successful genetic algorithms (GA) have been applied for the three-dimensional case (Cai et al. 2013).

1.1 Related works

In contrast to the bin-packing problem there are fewer research papers in the field of the variable-sized bin packing problem (VSBPP) and most studied problems are one-dimensional. In the majority of papers we can read about lower bounds and solution methods. VSBPP is an NP-hard problem and there are exact and approximation algorithms, and the latter can be divided into heuristics and metaheuristics.

-

(a)

Exact methods

There exist exact methods for the 1DVSBPP and the 2DVSBPP, too. For the 1DVSBPP Correia et al. (2008) and Haouari and Serairi (2011) developed branch-and-bound algorithms, Baldi et al. (2014) published branch-and-price and beam search algorithms. For the 2DVSBPP Pisinger and Sigurd (2005) developed a branch-and-bound algorithm and Liu et al. (2011) published a dynamic programming solution.

-

(b)

Heuristics

For the 1DVSBPP Chu and La (2001) developed 4 approximation algorithms and analysed their worst-case performances; Epstein and Levin (2012) published an approximation scheme.

There are a lot of heuristic methods. For the 1DVSBPP, published examples are the IBFD and IFFD (Kang and Park 2003), the FFDLR and FFDLS (Friesen and Langston 1986), the SSP1, SSP2, SSP3 and SSP4 (Haouari and Serairi 2009). Further heuristics were published among others by Belov and Scheithauser (2002), Alves and De Carvalho (2007), Crainic et al. (2011), Maiza et al. (2012), Bang-Jansen and Larsen (2012) and Hemmelmayr et al. (2012).

For the 2DVSBPP there is only one heuristic published, the 2SVSBP heuristic of Ortmann et al. (2010). It is a two-stage heuristic, in the first stage 2SVSBP packs the rectangles on strips with a level-packing heuristic of the strip-packing problem and then the levels are packed into large bins from the strips. In the second, repacking stage the rectangles are repacked from these large bins into smaller ones to reduce the wasted space. In the repacking 2SVSBP uses the level-packing heuristic again.

Some of the algorithms for the one- and two-dimensional variable-sized bin packing problems have two phases. In the first one they pack the items into bins and in the second phase they try to minimize the wasted space by repacking the items from larger bin into a smaller one (See Friesen and Langston 1986; Kang and Park 2003; Ortmann et al. 2010). There are also repacking strategies that solve the problem in one step like the goal-driven approach of Wei et al. (2013), that runs an improving procedure to reduce the total costs of bins after a feasible solution has been found.

-

(c).

Metaheuristics

The metaheuristics are able to find the global optimum with a high degree of probability. For the 1DVSBPP Blum et al. (2010) proposed a variable neighbourhood search, Haouari and Serairi (2009) developed a genetic algorithm, and Monaci (2001) published heuristics that use elements of exact methods, too. For the 2DVSBPP Wei et al. (2013) published a goal-driven method and Alvarez-Valdes et al. (2012) developed an algorithm based on GRASP and Path Relinking. The method of Alvarez-Valdes et al. (2012) solves the 3D version of the problem too. The genetic algorithm of Cai et al. (2013) works with an EDA and solves the 3D version of VSBPP with rotation.

To the best of our knowledge nobody published a successful evolutionary method (EDA) for 2DVSBPP that we can compare with other methods based on the benchmark test problems of 2DVSBPP.

1.2 Our contribution

Our contribution, therefore, is a new hybrid EDA for 2DVSBPP (named variable-sized bin packing estimation of distribution algorithm, VBEA) and its key features are the following:

-

To generate descendants VBEA uses it either a probability model or selection and mutation operators.

-

We use three new local searches to increase the number of fully filled, or almost full bins of the descendant.

-

A threshold value is used to label a bin “almost full”, this influences the quality of the result.

-

For packing the rectangles into the bins we use a special strategy with two placement heuristics that pack always only one group (one to three) of rectangles.

The remaining part of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes some important elements of the algorithm; Sect. 3 describes the main steps of the VBEA. The computational results are reported in Sect. 4, and the conclusions form Sect. 5.

2 Preliminaries

Let us first examine some important elements of our algorithm. They are the schematic structure of VBEA, the evaluation values and functions, the fitness function, the probability model, the bin-packing procedure and the Unified Computational Time.

2.1 Schematic structure of VBEA

The schematic structure of our algorithm shows the main steps of the algorithm without the details of the steps, operations, and procedures.

2.2 Evaluation values and functions

First we give some basic definitions. Let P be the actual population. Then \(P\, = \,\left\{ {I_{1} , \ldots ,I_{k} } \right\}\) where each Ii is an individual (i.e. a feasible solution to our problem). Each \(I_{i} ,\;\;i\, = \,1, \ldots ,k\) contains bins filled with items from the input, and the items placed in the same bin satisfy the packing conditions (no overlapping, and sides are parallel to the appropriate sides of the bin).

and

where \(B_{i,l} \cap B_{i,j}=\varnothing \;\;{\text{and}}\;\; \cup B_{i,j} = R\)

The fullness proportion limit—denoted by λ—represents a load-limit of the bins, 0 < λ ≤ 1. The value of λ is a given parameter of the procedure, usually its value has been chosen from the set {0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 0.99}. Let

be the fullness proportion of the bin Bi,j. It is clear that Fi,j ≤ 1. If

then we declare the bin full, and it belongs to the set of full bins (FB). Otherwise the bin belongs to the set of non-full bins (NFB).

If Ij is an individual then the utilization rate for Ij is

2.3 Fitness function

The fitness function (f) computes the value that measures the quality of the packing in the individual, lower values correspond to better packing. Our fitness function uses a positional notation of a hierarchy of two or three separate fitness parts, corresponding to three functions measuring different aspects of the quality of packing: f = f2 + f1 or f = f3 + f2 + f1.

The least significant part (f1) measures the improvement of the fullness proportions after attempting to reallocate rectangles among the bins. It is an important part of the fitness function because the operators and local searches of the algorithm can modify the fullness proportions and based on the modifications we can delete bins or can search for other bins to use. These modifications can improve the utilization rate or the cost value too.

In the f1 part of the fitness function we use the idea of the cost function of Falkenauer (1996): maximize

where nb is the number of non-empty bins, Fk is the fullness proportion of bin k \(\left( {k\, = \,1,2, \ldots ,nb} \right)\) and q > 1. The constant q expresses the concentration on the extremist bins in comparison to the less filled ones. The author found that q = 2 gave good results. Because 1 ≥ fBPP and \(nb - \sum\nolimits_{k = 1}^{nb} {(F_{k} )^{q} } \ge 0\) we define for the f1 part of the fitness function as the following function:

The second part of the fitness (f2) watches the utilization rate of the solution (we use it as an integer number). If I is the individual then the utilization rate for I is

and

where a is a constant. Because we want to minimize the utilization rate, f2 needs to have a bigger weight in the fitness function than f1, so the value of f2 has to be always larger than the value of f1 in the fitness function. The constant a ensures this dominance. The value of a depends on the problem, e.g. at our benchmark test sets the value of a can be 7.

If the costs are independent of the areas of the bins, then the goal is to find the solution with minimal cost, so there is a third part in the fitness function:

where Ck is the cost of the bin k (k = 1,2,…,nb) and b is a constant. Including f3 in the fitness function is not accompanied by any other changes to the algorithm. In this case we want to minimize the cost, so the value of f3 has to be always the largest in the fitness function. The constant b ensures this dominance. The value of b also depends on the problem, e.g. at our benchmark test sets the value of b can be 10.

2.4 The probability model

With the relative pair frequency matrix we can estimate the probability that the ith and the jth rectangles used to be in the same bin. For this we have to know the frequency of every pair of rectangles—how often they are in the same bin in the best individuals. As “best individuals” we take the best 20% of the population based on fitness values (Borgulya 2019, 2021).

Let G be an n × n matrix that stores the relative frequencies of the pairs. Every rectangle has a row and a column in the matrix. G is a symmetric matrix, and the values of the main diagonal in the matrix are nulls. It suffices to use the upper triangular matrix of G in the algorithm. G is updated throughout the evolution process using the”best individuals”. We update G after every kgenth generation (e.g., kgen = 10). The updating process is as follows:

Let ΔG be of the same size triangular matrix to G. Let Gij be the collected relative frequency of the ith and the jth rectangle (a pair) in common bins until a given kgenth generation. We update the elements of the matrix G with the element of ΔG

where ΔGi,j is the relative frequency of the ith and the jth rectangles in common bins based on the”best individuals” of the kgenth generation and α denotes some relaxation factor (e.g., α = 0.2). Algorithm 1 outlines this process.

We use the matrix G to estimate the probability of pairs of rectangles. The formula

gives the estimated probability that the ith and the jth rectangles are in the same bin. Let maxpr be the maximum of the pri,j estimated probabilities \(\left( {i\, = \,1,2, \ldots ,n\; \, j\, = \,1,2, \ldots ,n} \right)\).

2.4.1 Sampling-G procedure

Sampling-G can repack the non-full bins of an individual or generates a new individual by packing all the rectangles. Let Q be a set of rectangles \(Q\, = \,\left\{ {r_{1} ,r_{2} , \ldots ,r_{k} } \right\},k\, \le \,n\). The rectangles from Q are available for packing with Sampling-G.

The procedure repeats the following steps for every new bin:

-

1.

It “pre-filters” the rectangles. During the pre-filtering the chosen rectangles are placed into a set (we call it S). It selects rectangles based on the probability model from the not yet selected rectangles of Q considering both the sizes and the areas of the rectangles. The selected rectangles will be eligible to be placed into the new bin, but likely not all will be place able as during the pre-filtering we do not check place ability.

First we choose a rectangle together with a bin of corresponding type. Let’s call the chosen bin BOX and let’s use a capacity variable to ensure the area restriction. Let the value of capacity be the area of BOX, during the pre-filtering we pay attention to the areas of the rectangles so as the total area of the chosen rectangles doesn’t exceed capacity. The pre-filtering ends when no further rectangle can be chosen from Q or the total area of the rectangles reaches capacity.

-

2.

It tries to pack the rectangles from S into the BOX. To pack the rectangles into the bin the algorithm uses the strategy of randomly choosing one of two placement heuristics, that pack always only one group of rectangles (one to three rectangles).

Algorithm 2 outlines this process.

2.4.2 Bin-packing procedure for a 2-dimensional bin

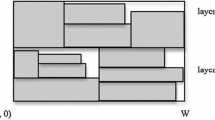

In the literature the state of a bin is usually represented by a list of points, or horizontal line segments where the points or segments are candidate positions to load a new rectangle. The most important representations are the Corner Points (Martello et al. 2000), the Extreme Points (Crainic et al. 2008) and the skyline (Wei et al. 2013). We apply the skyline representation (contour of a set of consecutive vertical bars) in our algorithm that gives horizontal line segments (\(s_{1} ,s_{2} , \ldots ,s_{k}\)). The skyline si is a triplet (\(x_{i,s} ,x_{i,e} ,y_{i}\)) where xi,s and xi,e are the two first coordinates and yi is the second coordinate of the skyline si. Then for any subsequent skyline \(y_{i - 1} \, \ne \,y_{i} \, \ne \,y_{i + 1}\), and \(x_{i,e} \, = \,x_{i + 1,s}\) (Fig. 1). Initially a single line segment corresponds to the bottom of the empty bin.

We can place a rectangle on a single horizontal segment of the skyline; or we can place a larger rectangle over multiple neighbouring segments of the skyline. Neighbouring segments with m + 1 segments are \(s_{j} ,s_{j + 1} , \ldots ,s_{j + m}\), where \(j\, = \,1, \ldots ,k - m\, + \,1; \, 1\, \le \,m\, < \,k\).

The Bin-packing procedure tries to pack the rectangles into the bin. It uses two placement heuristics HP1 and HP2 that always pack only one group (one to three) of rectangles. It applies HP1 with a probability of 0.34 and with a probability of 0.66 applies HP2. The placement heuristics search an appropriate segment (or neighbouring segments) of the skyline for the next rectangle. When all rectangles have been considered for packing, the procedure ends. At the end non-packed rectangles may remain in S.

HP1 is a modified version of the BL heuristic; HP2 is a modified version of the BF heuristic.

A fixed ordered sequence is used for the best-known placement heuristic: the “bottom up, left justified” (BL) heuristic (Baker et al. 1980). BL first sorts the rectangles according to their areas and then starts with each rectangle from the top-right corner. Then, it slides the rectangle as far as possible to the lowest location and then, as far as possible to the left of the locations. HP1 places only a single rectangle; it uses the BL packing principle. Without sorting the rectangles, it places the next not-yet-placed rectangle from S to the lowest segment (or neighbouring segments) possible. If the height of the packed area in the bin would exceed the height of the bin, HP1 returns without packing this rectangle.

The “best fit” (BF) heuristic (Burke et al. 2004) dynamically chooses the rectangles. BF repeats two operations until all rectangles are placed; it searches for an available space as low as possible and then places the rectangle that fits the space best. HP2 applies the BF placement approach only to a single rectangle and then attempts to improve the result with the ibox local search. HP2 searches an available segment (or neighbouring segments) as low as possible and then dynamically selects a not-yet-placed rectangle that fits on this lowest available segment (or neighbouring segments) without exceeding the height of the bin. If the search was successful then HP2 packs the rectangle to the position found. If the search was not successful, then HP2 returns without packing.

If the width of the packed rectangle is smaller than the width of the segment (or neighbouring segments), HP2 also applies the ibox local search to fill in the space. ibox works in two steps. First, in order to form blocks it selects all those rectangles from S that are not packed yet and that are packable into the empty part of the segment (or neighbouring segments). It considers the rectangles in random order and chooses no more than 10 rectangles to form the block. In the second step, ibox builds blocks combining one, two or three rectangles from the selected rectangles and chooses the block that fits in the empty part of the segment (or neighbouring segments) and has the largest width.

After the application of HP1 or HP2 the algorithm updates the skyline. Figure 2 gives examples for the HP1 and HP2 heuristics.

2.5 Unified computational time

The methods of the comparative results section were executed on different computers, and so ″we calculated appropriate scaling factors to compare their running times. For this purpose, we used the CPU speed estimations provided in the SPEC standard benchmark″ (https://www.spec.org/cpu2006/results/cint2006.html) (Buljubašić and Vasques 2016). Based on the SPEC standard, we obtained CPU speeds for the different processors. With the CPU speeds we can calculate appropriate scaling factors to compare the running times of the different computers. We chose the CPU speed of the computer of a method as a reference, and the scaling factors are calculated as CPU speed/ reference CPU speed. Multiplying the CPU time of a processor by its scaling factor, we obtain a Unified Computational Time (UCT) for comparing their running times. (see Buljubašić and Vasques 2016; Quiroz-Castellanos et al. 2015).

3 The VBEA algorithm

Our VBEA generates only one descendant in every generation. First comes the initial population and next, in every generation it generates a descendant sampling the probability model, or applying the selection and mutation operators generates a descendant and improves the result with local searches (LS).

In case of certain instances, the algorithm might be ''stuck'' at one of the local optima. To enable escape towards a potential global optimum, the algorithm generates new, additional individuals. A new individual is also a descendant and can help to improve the optimising capability and the speed of the algorithm. Thus, new descendants are periodically inserted in the population until the maximum size of the population is reached.

Algorithm 3 shows the main steps of VBEA. The parameters of the algorithm are as follows:

tmax—the maximal size of the population.

tin—the first size of the population.

kgen—the algorithm is controlled in every kgenth generation.

timeend—the limit of the running time.

The next parameters will be explained later in this section:

LSn, LSm—parameters of the local searches.

tp—parameter of the truncation selection.

The operation of VBEA is as follows:

Input The algorithm reads the instance and the values of the parameters (described in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2). Every rectangle has a unique identification number.

Initial population The number of the individuals in the initial population is given in the tin parameter (e.g. 5). We generate the individuals of the initial population by repeating the Sampling-G procedure. In the first steps of the algorithm the elements of the G matrix are 0.5, so the resulted bins give a random, feasible individual.

Selection The algorithm selects an individual based on truncation selection. In this, only the best tp percentage of the population is considered as a potential parent.

Mutation The algorithm applies the mutation operator if FB is not empty. The operator uses the Sampling-G procedure to generate new bins in the descendant. First it deletes the NFB bins and stores their rectangles in the Q set. Next, it constructs bins from the rectangles of Q by Sampling-G.

Local searches. The algorithm applies three local searches: LS1, LS2 and LS3. The algorithm applies the LS1 or LS2 local searches LSn times on the descendant, and LSm times on the best individual. It applies LS1 with probability 0.5 and also with probability 0.5 applies LS2. These local searches can increase the fullness of some bins in the individual. At the end it applies the LS3 repacking local search to the descendant and to the best individual too (see Sect. 3.1).

Reinsertion This is a crowding technique that compares the descendant with the parent. The descendant may replace the parent if the descendant is better. If the descendant is an additional individual, the new descendant is inserted without any further analysis into the population.

Stopping criterion The algorithm is terminated if the running time limit is reached.

3.1 Local searches

There are three local search procedures: LS1, LS2 and LS3.

LS1 This chooses a random bin from NFB and tries to improve its fullness proportion. LS1 performs swaps a pair of rectangles between the chosen random bin and an other bin from NFB. For this, LS1 searches a bin with smaller fullness than the random bin, and tries a 1–1 rectangle swap between the bins. It accepts a swap if after the application of the bin–packing procedure the fullness of the random bin will be larger and the rectangles are packed into the bins. It tries the swap with all elements of the random bin.

LS2 This also chooses a random bin from NFB and tries to insert its rectangles into other bins from NFB. To increase the fullness of the bins it tries to insert 1 rectangle from the random bin to an other non-full bin where the fullness proportion is larger than the fullness of the random bin. It accepts an insert if after the application of the bin–packing procedure the fullness of the other bin will be larger and the rectangle is packed into the other bin.

LS3 This local search tries to reduce the wasted space in the bins of the individual by repacking the rectangles. For every bin it searches an empty random bin with smaller cost and tries to repack the rectangles into the random bin with the bin-packing procedure. If the repacking is successful it accepts the new bin.

4 Experimental results

The VBEA algorithm was implemented in C++. It was executed on iMAC with an Intel Core i5 2.5 GHz processor with 16 GB of RAM, running the MacOS Sierra 10.12.2 operating system.

We tested our algorithm on the benchmark instances of 2DVSBPP. The instances are available at http://www.vuuren.co.za/main.php. These benchmark instances are in use since 2010 and they are available in the papers dealing with 2DVSBPP.

The benchmark sets are the following:

-

P1, P2: Wang (1983). In P1 there are 2900 rectangles and 3 bin types; in P2 900 rectangles and 2 bin types.

-

M1, M2, M3: Hopper (2000) and Hopper and Turton (2002). These are test sets with 5–5 instances. In all instances there are 6 bin types. In the instances of M1 and M2 there are 100–100 rectangles, in the instances of M3 there are 150 rectangles.

-

PS: Pisinger and Sigurd (2005). In the test set there are 500 instances with variable bin costs. In all instances there are 6 bin types. In PS there are 10 subsets, every subset is composed of 50 instances, in each subset there are 10 instances for each value of n ∈ [20,40,60,80,100].

-

Nice, Path: Ortmann et al. (2010). Each test set consists of 170 instances with 2–6 bin types and with 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 or 500 rectangles.

The optimal solutions of the benchmark instances are known only for the Nice and Path sets. These instances were generated by cutting bins into rectangles, so they have optimal solutions with µ = 1. The other benchmark sets recently do not have a list of “best known” results because only a few papers are available with results of the benchmark sets. Lower bounds were not available either. Wei et al. (2013) in their algorithm use a procedure to determine the lower bounds of the benchmark test sets, but their lower bound results are not available. So the best we can compare to be the results from past publications.

4.1 Parameter selection

We analysed the process of VBEA to determine how the parameter values affect convergence. From the 857 test instances we chose 42 for parameter selection. For the parameter selection we want to work with few instances, but it was important that in the selected instances include a variety of large, typical and difficult instances too. So we choose the P1, P2 instances, the M1, M2 and M3 instance groups and the Path400 subset.

Because our algorithm has a similar structure and parameters to our earlier algorithm in (Borgulya 2021), we could accept the earlier parameter values. These parameters are the population size (tin and tmax parameters), the frequency of checks (kgen parameter), the number of generation in the first stage (itt parameter) and of the truncation selection parameter (tp). The accepted parameter values are tin = 5, tmax = 30, itt = 5, kgen = 5 and tp = 0.1.

We analysed the values of the LSn, LSm parameters of the local searches together. We tried different combinations of the parameter values. We can conclude the following: for LSn, LSm we found several suitable values and the values of the parameters depended on n. We achieved our the best results using the following values (among similarly suitable values):

-

if n ≤ 100 LSn = 500, LSm = 500

-

if 100<n ≤ 200 LSn = 300, LSm = 300

-

if 200<n LSn = 2, LSm = 50 or LSn = 50, LSm=2.

The fullness proportion limit (λ) of a bin is also very important. If λ is smaller-and-smaller then the number of almost full bins can increase in the FB set. The mutation operators and local searches work only on NFB so the speed of the algorithm can increase with smaller λ. But the algorithm cannot improve the quality of the solutions at every value of λ. Table 1 shows a comparison of the best results with different λ values on three test sets. The table gives the average utilization rates based on the best solutions for each sets. We got the best results (bold values) between 0.85 and 0.95.

For the time limit we found that a duration of 120 CPU seconds is sufficient in most of the test problems. Hence the time limit is 120 s (timeend = 120). In the case of the P1 instance we had to use larger time limit: timeend = 400 s (the seconds are in UCT time).

4.2 Computation experience

VBEA was run 10 times on each test instance of the test sets, and we provide the average and best results for every instance. For every test set we compute the average results of the instance averages and the average of the best instance results too. Table 2 gives a summary of the average results for every test set.

Table 2 shows the names of the test sets (set), the number of rectangles in the instances (n), the number of instances in the set (inst). At the average results we see the average utilization rate of the instances in the set (μ), the average of the standard deviation of μ (SD) and the average number of used bins in the solutions of the instances (bin_n). At the best results we see the average best utilization rate of the instances in the set (µb) and the average number of used bins in the best solutions of the instances (bbin_n). First we realised in Table 2 that the algorithm could reach the same μ result of an instance with different numbers of bins. So the average number of the used bins is very rarely an integer number.

We got the best results on the M1, M2 and M3 test sets. The SD values of M1, M2 and M3 are 0.00, so the utilization rates of ten runs of the same instance are the same. The μ and μb results of a set are the same, the results are over 0.99. But the bin_n and bbin_n values can be different. The algorithm could reach the same μ result of an instance with different numbers of used bins and with different types of bins. E.g. in case of set M2 after the 10 runs we got 10*5 results. In the results every μ value is the same, but the numbers and types of used bins can be different. The average number of used bins (bin_n) is 11.1, and among the 5 best results the average bbin_n is 10.2.

The results of the other test sets are similar: the μb of the best results are 0.96–0.98 and the μ of the average results are lower by 0.04–0.05. The standard deviations of μ are the largest for the P1, P2 and Path sets, they are difficult problems for our algorithm.

4.2.1 Comparative results

For the comparison of the results we chose four methods: the 2SVSBP heuristic with the stack ceiling (SC) and with the stack ceiling with re-sorting (SCR) algorithms (Ortmann et al. 2010), the goal-driven (GDA) method (Wei et al. 2013) and the GRASP/ Path Relinking (GRASP/PR) method (Alvarez-Valdes et al. 2012). The SC and SCR run on an XP with Intel Core 2 duo CPU with 3.0 GHz and 4 GB RAM; it was coded in Visual Basic. GDA run on an IntelXeon E5430 with 2.66 GHz Quad Core CPU and 8 GB RAM; it was coded in C++. GRASP/PR run on a Pentium Mobile at 1500 MHz with 512 Mbytes of RAM; it was coded in C++.

The methods of the comparative results section were executed on different computers, so we calculated appropriate scaling factors to compare their UCT running times. The speed of the computer of GDA, SC, GRASP/PR and VBEA where: 21.2, 16.2, 9.2 and 30.5. We chose the CPU speed of the computer of GDA as a reference, and the scaling factors used were: 1, 0.76, 0.43 and 1.43.

In Table 3 we see the results of the two heuristics SC, SCR and of the three metaheuristics GDA, VBEA and GRASP/PR. SC and SCR give the average utilization rate of each test sets. We can compare the average results in the case of VBEA on all test sets and in the case of GRASP/PR on the PS test set. The average results of VBEA are better on all test sets by an average 0.07 compared to the other heuristics. Only at the P2 and M1 sets are there smaller differences: our VBEA is only better by 0.03–0.04. On the PS set GRASP/PR is also better by 0.08 than the heuristics. We can compare the two metaheuristics too: the average result of VBEA on PS is also better than the result of GRASP/PR.

Only the best results of GDA are published, so we compare the best results of VBEA and GDA. VBEA has better results on all test sets and the average μb is higher by 0.04 than the average μb of GDA. In the case of P1 and PS VBEA is higher by 0.08; in the case of Nice, Path the differences are smaller. In case of GDA, the bbin_n values have been published, too. It is not a goal in the problem to minimize the number of bins, however, comparing the bbin_n values we can infer an aspect of the operation of the methods. With the exception of Nice and Path sets the GDA uses less bins for all other sets than VBEA, so the GDA must use larger bins to store the rectangles and in total less of them than VBEA uses. Conversely, the VBEA needs to use a larger number of smaller bins with the larger count of bins. The better results of VBEA demonstrate that in case of the benchmark test sets it’s a better strategy to use smaller bins.

We can compare the running times too. In case of VBEA we defined the run time as the time required until reaching the best result within the time limit (timeend). Table 4 gives the average and the best running times. The metaheuristics require significantly longer CPU times than the simpler heuristics that run extremely fast. We can compare the average times on the set PS between the VBEA and GRASP/PR. GRASP/PR is a little bit faster than VBEA. As the utilization rate result of GRASP/PR is weaker then VBEA′s one, it is a question how GRASP/PR can improve the utilization rate allowing a longer running time.

In the comparison of the best times of VBEA and GDA we can see that VBEA is faster on the sets PS, Nice, Path, whereas GDA is faster on the sets P1, P2, M1, M2, M3. GDA is significantly faster at P2 than VBEA, and it is significantly slower at PS, Nice and Path than VBEA. But based on the average of the used running times over the test instances VBEA is twice faster than GDA.

In case of the set P1 there is a bigger difference. If we compare the results as the function of the running times, we find that about at 45 s (UCT time) the μ of VBEA is 0.90 and GDA reaches similar result only at 225.9 s. So VBEA is significantly faster on the set P1 and it finds a better solution in the longer running times. We can see these details in Fig. 3, where the convergence behaviors of the two largest problems P1 and P2 are available.

As conclusion we can say that VBEA outperforms the heuristics, GDA and GRASP/PR.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we described a hybrid EDA for 2DVSBPP; to our knowledge this is the first EDA with good results for this problem. Our algorithm uses a probability model or selection and mutation operators to generate descendants. The mutation operator is based on the probability model. The algorithm improves the quality of the solutions with local search procedures.

In the algorithm we use some new elements and techniques: composite fitness function, a strategy recognising almost full bins, local searches to increase the fullnesses of some bins and a special packing strategy with two placement heuristics. Using these elements the results are good, the algorithm outperforms the earlier published methods.

In the future we plan to apply the ideas of the algorithm on other types of the bin packing problems.

References

Alvarez-Valdes R, Parreño F, Tamarit JM (2012) A GRASP/Path Relinking algorithm for two- and three-dimensional multiple bin-size bin packing problems. Comput Oper Res 40(12):3081–3090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2012.03.016

Alves CJ, De Carvalho MV (2007) Accelerating column generation for variable sized bin-packing problems. Eur J Oper Res 183(3):1333–1352

Baker BS, Coffman EG, Rivest RL (1980) Orthogonal packing in two dimensions. SIAM J Comput 9(4):846–855

Baldi MM, Crainic TG, Perboli G, Tadei R (2014) Branch-and-price and beam search algorithms for the Variable Cost and Size Bin Packing Problem with optional rectangles. Ann Oper Res 222(1):125–141

Bang-Jansen J, Larsen R (2012) Efficient algorithms for real-life instances of the variable size bin packing problem. Comput Oper Res 39(11):2848–2857

Belov G, Scheithauser G (2002) A cutting plane algorithm for the one dimensional cutting stock problem with multiple stock lengths. Eur J Oper Res 141(2):274–294

Blum C, Hemmelmayr V, Hernández H, Schmid V (2010) Hybrid algorithms for the variable sized bin packing problem. LNCS 6373:16–30

Borgulya I (2019) An EDA for the 2D knapsack problem with guillotine constraint. CEJOR 27:329–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-018-0551-x

Borgulya I (2021) A hybrid evolutionary algorithm for the offline Bin Packing Problem. CEJOR 29:425–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-020-00695-5

Buljubašić M, Vasquez M (2016) Consistent neighborhood search for one-dimensional bin packing and two-dimensional vector packing. Comput Oper Res 76:12–21

Burke EK, Kendall G, Whitwell G (2004) A new placement heuristic for the orthogonal stock-cutting problem. Oper Res 52:655–671

Cai Y, Huaping C, Rui X, Hao S, Xueping L (2013) An estimation of distribution algorithm for the 3D bin packing problem with various bin sizes. LNCS 8206:401–408

Chu C, La R (2001) Variable-sized bin packing: tight absolute worst-case performance ratios for four approximation algorithms. SIAM J Comput 30:2069–2083

Correia I, Gouveia L, Saldanha-da-Gama F (2008) Solving the variable size bin packing problem with discretized formulations. Comput Oper Res 35:2103–2113

Crainic TG, Perboli G, Tadei R (2008) Extreme point-based heuristics for three-dimensional bin packing. Informs J Comput 20(3):368–384

Crainic TG, Perboli G, Rei W, Tadei R (2011) Efficient lower bounds and heuristics for the variable cost and size bin packing problem. Comput Oper Res 38(11):1474–1482

Epstein L, Levin A (2012) Bin packing with general cost structures. Math Program 132(1–2):355–391

Falkenauer E (1996) A hybrid grouping genetic algorithm for bin packing. J Heuristics 2:5–30

Friesen DK, Langston MA (1986) Variable-sized bin packing. SIAM J Comput 15(1):222–230

Garey M, Johnson D (1979) Computers and intractability: a guide to the theory of NP-completeness. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco

Haouari M, Serairi M (2009) Heuristics for the variable sized bin-packing problem. Comput Oper Res 36:2877–2884

Haouari M, Serairi M (2011) Relaxations and exact solution of the variable sized bin packing problem. Comput Optim Appl 48:345–368

Hemmelmayr V, Schmid V, Blum C (2012) Variable neighbourhood search for the variable sized bin packing problem. Comput Oper Res 39:1097–1108

Hopper E (2000) Two-dimensional Packing Utilising Evolutionary Algorithms and Other Meta-heuristic Methods, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wales, Cardiff School of Engineering

Hopper E, Turton BCH (2002) An empirical study of meta-heuristics applied to 2D rectangular bin packing—part I. Studia Inform Universalis 2:77–92

Kang J, Park S (2003) Algorithms for the variable sized bin packing problem. Eur J Oper Res 147(2):365–372

Liu Y, Chu C, Wang K (2011) A dynamic programming-based heuristic for the variable sized two-dimensional bin packing problem. Int J Prod Res 49(13):3815–3831

Maiza M, Labed A, Radjef MS (2012) Efficient algorithms for the offline variable sized bin-packing problem. J Glob Optim. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10898-012-9989-x

Martello S, Pisinger D, Vigo D (2000) The three-dimensional bin packing problem. Oper Res 48(2):256–267

Monaci M (2001) Algorithms for packing and scheduling problems, Ph.D. Thesis, Università di Bologna, Bologna

Ortmann FG, Ntene N, Van Vuuren JH (2010) New and improved level heuristics for the rectangular strip packing and variable-sized bin packing problems. Eur J Oper Res 203:306–315

Pisinger D, Sigurd M (2005) The two-dimensional bin packing problem with variable bin sizes and costs. Discrete Optim 2:154–167

Quiroz-Castellanos M, Cruz-Reyes L, Torres-Jimenez J, Gómez C, Héctor S, Huacuja JF, Alvim ACF (2015) A grouping genetic algorithm with controlled gene transmission for the bin packing problem. Comput Oper Res 55:52–64

Wang PY (1983) Two algorithms for constrained two-dimensional cutting stock problems. Oper Res 31:573–586

Wei L, Oon WC, Zhu W, Lim A (2013) A goal-driven approach to the 2D bin packing and variable-sized bin packing problems. Eur J Oper Res 224:110–121

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pécs. The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borgulya, I. A hybrid estimation of distribution algorithm for the offline 2D variable-sized bin packing problem. Cent Eur J Oper Res 32, 45–65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-023-00858-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-023-00858-0