Abstract

Better characterization of the geochemical evolution of groundwater south of Grand Canyon, Arizona (USA), is needed to understand natural conditions and assess potential effects from breccia-pipe uranium mining in the region. Geochemical signatures of groundwater at 28 sampling locations were evaluated; baseline concentrations for select trace elements (As, B, Ba, Cr, Li, Mo, Rb, Se, Sr, Th, Tl, U, V) were established, and anomalous chemistry characteristics were identified. Concentrations at some groundwater sites exceeded the USEPA drinking water standard for As of 10 μg/L (Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu, and Warm Springs) and U of 30 μg/L (Salt Creek Spring). Four springs from the study area (Blue, Havasu, Fern, and Warm Springs) had unique chemistry, which may indicate a deep flow path or potential contribution of fluids from lower in the crust. Other springs in the study area were distinguished by major anion water type: sulfate, bicarbonate, and a mixture of the two. Water type distinctions were somewhat spatially segregated, with sulfate type present on the western side of the study area, bicarbonate type on the eastern side, and a mixture of the two interspersed between the endmember sites. Sulfate-type water from this study area had low strontium isotopic ratio (87Sr/86Sr) values. The location of spring discharge within single drainages of the Grand Canyon may influence chemistry, as groundwater discharging from bedrock was altered after flowing through alluvial material. Geochemical analysis of groundwater in Grand Canyon indicates the importance of continued monitoring and better understanding of short-term chemical fluctuations.

Résumé

Une meilleure caractérisation de l’évolution géochimique des eaux souterraines au sud de Grand Canyon, en Arizona (États-Unis d’Amérique), est nécessaire pour comprendre les conditions naturelles et évaluer les effets potentiels de l’extraction de l’uranium au sein d’une structure verticale bréchique dans la région. Les signatures géochimiques des eaux souterraines collectées au niveau de 28 sites d’échantillonnage ont été analysées; les concentrations naturelles en certains éléments traces (As, B, Ba, Cr, Li, Mo, Rb, Se, Sr, Th, Tl, U, V) ont été établies, et des caractéristiques chimiques anormales ont été identifiées. Les concentrations de certaines eaux souterraines dépassent les normes de l’Agence de la Protection de l’Environnement (USEPA) des Etats-Unis d’Amérique pour l’eau potable, de 10 μg/L pour l’arsenic (Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu et Warm Springs) et de 30 μg/L pour l’uranium (Salt Creek Spring). Quatre sources de la zone d’étude (Blue, Havasu, Fern et Warm Springs) présentent une chimie singulière, ce qui peut indiquer des circulations profondes ou une contribution potentielle de fluides issus d’une plus grande profondeur dans la croute. D’autres sources dans la zone d’étude se distinguent selon leur anion majoritaire: sulfate, bicarbonate, et un mélange des deux. Les faciès d’eau se distinguent en quelque sorte spatialement; le faciès sulfaté est présent sur le côté ouest de la zone d’étude, alors que le faciès bicarbonaté occupe le côté est. De plus, un mélange des deux faciès s’exprime entre les deux orientations. Les eaux de type sulfaté de cette zone d’étude présentent un faible rapport isotopique du strontium (87Sr/86Sr). L’alignement des sources selon les axes singuliers de drainage du Grand Canyon peut influencer la chimie, les eaux souterraines issues du substratum rocheux sont altérées après avoir circulé dans des matériaux alluviaux. L’analyse géochimique des eaux souterraines dans le Grand Canyon montre l’importance d’une surveillance continue et d’une meilleure compréhension des fluctuations chimiques à court terme.

Resumen

Se necesita una mejor caracterización de la evolución geoquímica de las aguas subterráneas al sur del Gran Cañón, Arizona (EEUU), para comprender las condiciones naturales y evaluar los posibles efectos de la extracción de uranio a partir de chimeneas de brechas en la región. Se evaluaron las firmas geoquímicas de las aguas subterráneas en 28 lugares de muestreo; se establecieron concentraciones de referencia para oligoelementos seleccionados (As, B, Ba, Cr, Li, Mo, Rb, Se, Sr, Th, Tl, U, V) y se identificaron características químicas anómalas. Las concentraciones en algunos sitios de aguas subterráneas excedieron el estándar de agua potable de la USEPA para As de 10 μg/L (Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu, y Warm Springs) y U de 30 μg/L (Salt Creek Spring). Cuatro manantiales del área de estudio (Blue, Havasu, Fern, y Warm Springs) tenían una química única, lo que puede indicar un camino de flujo profundo o una contribución potencial de fluidos de más abajo en la corteza. Otros manantiales del área de estudio se distinguieron por el tipo de agua aniónica principal: sulfato, bicarbonato y una mezcla de ambos. Las distinciones de los tipos de agua estaban algo segregadas espacialmente, con el tipo de sulfato presente en el lado occidental del área de estudio, el tipo de bicarbonato en el lado oriental, y una mezcla de los dos intercalados entre los sitios de los miembros finales. El agua de tipo sulfatada de esta zona de estudio tenía valores bajos de relación isotópica de estroncio (87Sr/86Sr). La ubicación de la descarga de los manantiales dentro de los drenajes individuales del Gran Cañón puede influir en la química, ya que las aguas subterráneas que se descargan desde el basamento se alteraron después de fluir a través del material aluvial. El análisis geoquímico de las aguas subterráneas del Gran Cañón indica la importancia del monitoreo continuo y de una mejor comprensión de las fluctuaciones químicas a corto plazo.

摘要

需要更好地表征美国亚利桑那州大峡谷南部地下水的地球化学演化,以此弄清自然条件并评估该地区火山角砾岩筒的铀矿开采的潜在影响。对28个采样点的地下水地球化学特征进行了评估;确定了选定的微量和痕量元素(As,B,Ba,Cr,Li,Mo,Rb,Se,Sr,Th,Tl,U,V)的基线浓度,并识别了异常的化学特征。一些地下水取样点的浓度超过了USEPA饮用水标准,As达到10 μg/L(红峡谷,矿工,JT,Havasu和暖泉)和U达30 μg/L(Salt Creek Spring)。来自研究区域的四个泉(蓝色,哈瓦苏,蕨类和暖泉)具有独特的化学性质,这可能表明深层的流动路径或地壳下部流体的潜在贡献。研究区的其他泉水以主要的阴离子水类型为特征:硫酸根,碳酸氢根和两者的混合物。水化学类型划定在空间上是分隔的,研究区域的西侧是硫酸盐类型,东侧是碳酸氢盐类型,以及两种混合物在东西侧终端场地之间。该研究区的硫酸盐型水的锶同位素比值较低(87Sr/86Sr)。大峡谷单条排泄通道中泉排泄的位置可能会影响化学反应,因为基岩中排泄出来的地下水在流经冲积物质后发生了变化。大峡谷地下水的地球化学分析表明了持续监测的重要性和更好地了解短期化学波动。

Resumo

É necessária uma melhor caracterização da evolução geoquímica das águas subterrâneas ao sul do Grand Canyon, Arizona (EUA), para entender as condições naturais e avaliar os possíveis efeitos da mineração de urânio com tubos de Brecha na região. As assinaturas geoquímicas das águas subterrâneas foram avaliadas em 28 locais de amostragem; as concentrações de linha de base para os oligoelementos selecionados (As, B, Ba, Cr, Li, Mo, Rb, Se, Sr, Th, Tl, U, V) foram estabelecidas e as características químicas anômalas foram identificadas. As concentrações em alguns locais de águas subterrâneas excederam o padrão de água potável da USEPA para As de 10 μg/L (Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu, and Warm Springs) e U de 30 μg/L (Salt Creek Spring). Quatro fontes da área de estudo (Blue, Havasu, Fern e Warm Springs) possuíam uma química única, o que pode indicar um caminho de fluxo profundo ou a potencial contribuição de fluidos de menor profundidade na crosta. Outras fontes na área de estudo foram distinguidas pelo principal tipo de água aniônica: sulfato, bicarbonato e uma mistura das duas. As distinções do tipo água foram um pouco segregadas espacialmente, com o tipo sulfato presente no lado oeste da área de estudo, o tipo bicarbonato no lado leste e uma mistura dos dois intercalados entre os locais dos membros finais. A água do tipo sulfato proveniente dessa área de estudo apresentava baixos valores de razão isotópica de estrôncio (87Sr/86Sr). A localização da descarga de nascentes dentro de drenagens únicas do Grand Canyon pode influenciar a química, pois a descarga das águas subterrâneas do leito rochoso foi alterada após o fluxo através do material aluvial. A análise geoquímica das águas subterrâneas no Grand Canyon indica a importância do monitoramento contínuo e do melhor entendimento das flutuações químicas de curto prazo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On the arid South Rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona (USA), water is a limited resource. Local populations and ecosystems are dependent on groundwater. The geochemical evolution of the groundwater as it moves through the subsurface, affecting the suitability for consumption, is not well understood. Increased development, uranium mining, and climate change may introduce changes to the groundwater system and focused studies are needed to understand the timing and effects from these changes. In 2012, then US Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, initiated a removal of over 1 million acres in three segregation areas of federal land (north, east, and south) in the Grand Canyon region from new uranium mining activities for the following 20 years, subject to valid existing rights (US Department of the Interior 2012). A key factor in the decision for the withdrawal was the limited amount of scientific data and resulting uncertainties on the potential effects of uranium mining activities on cultural, biological, and water resources in the area. The US Geological Survey (USGS) has been conducting studies to address the uncertainties of potential uranium mining effects.

Purpose and scope

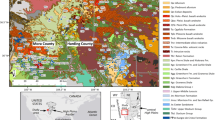

The purpose of this report is to document understanding of the geochemical evolution of groundwater discharging from the Redwall-Muav aquifer south of Grand Canyon. Establishing an understanding of the geochemical signature of the groundwater discharging south of Grand Canyon will provide baseline geochemical information, identify anomalous groundwater samples and their sources, and help elucidate what potential geochemical changes may occur due to breccia-pipe uranium mining. The scope of this report includes as assessment of 28 groundwater sites (25 springs and 3 wells) located south of the Grand Canyon spanning from Blue Spring in the eastern to Warm Spring in the western parts of the study area (Fig. 1). Targeted samples were collected for this study from 2016 to 2018 and the data were combined with data from previous studies of South-Rim groundwater chemistry by Monroe et al. 2005, Bills et al. 2007, and USGS 2019.

Map showing the study area including groundwater sample locations and known breccia pipe deposits, some of which are mineralized. Shaded relief represents the topographic elevation changes where the color tan represents lower elevations and purple to white represent higher elevations. Squares represent samples collected between 2016 and 2018 and circles represent samples collected by other USGS studies between 2000 and 2015. Location of mineralized breccia pipes can be found in the following references: Alpine 2010; Brown et al. 1992; Chenoweth 1986; Wenrich et al. 1997; Sutphin and Wenrich 1989; Van Gosen and Wenrich 1989, 1991; Finch et al. 1990; Wenrich 1992; Wenrich and Aumente-Modreski 1994; Gardner 1998; Mazeika 2002.

Major ion and trace element chemistry was used to characterize the groundwater and evaluate changes in groundwater chemistry as compared to historical sample collection. The dissolved ion chemistry was used to characterize water type and as input for statistical analysis that formally determined the similarities and differences between groundwater along the South Rim and helped develop a conceptual model of groundwater geochemical evolution. Groundwater recharge sources, proposed flow paths, and estimated mean ages (Solder et al. 2020; Solder and Beisner 2020; USGS 2019) were used in conjunction with dissolved ion and isotopic data in conceptual model development. Isotopic ratios of uranium and strontium provided additional evidence of flow paths through stratigraphic sections and the extent of water–rock interaction.

Hydrogeologic setting

The study area is located in the Colorado Plateau physiographic province. The youngest rocks in the study area are Tertiary volcanic rocks primarily present to the south of Grand Canyon which are underlain by Mesozoic and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. Groundwater samples in this study were from the Redwall-Muav aquifer (Mississippian to Cambrian in age), which is lower in the Paleozoic stratigraphic sequence. A less significant portion of groundwater is present in the perched Coconino aquifer (Permian in age) near the top of the Paleozoic sequence. Water is thought to recharge the system to the south of Grand Canyon near the San Francisco peaks (Crossey et al. 2009; Bills et al. 2007; Solder et al. 2020; Solder and Beisner 2020) and some additional smaller areas of localized recharge closer to the South Rim have been proposed (Knight and Pool 2016; Solder et al. 2020; Solder and Beisner 2020; Fig. 2). The extensive system of fractures, faults, and karst features in the area control general groundwater flow direction and speed, but the magnitude of influence and location of these features are not well constrained (Huntoon 1974; Jones et al. 2017).

a Location of the study area south of Grand Canyon (red boundary represents the areas removed from new uranium mining claims (US Department of the Interior 2012). b Conceptual cross section demonstrating preferential groundwater pathways facilitated by structural features. Geology derived from Ulrich et al. (1984), Billingsley (2000), and Billingsley et al. (2006)

The study of groundwater geochemistry south of Grand Canyon has a rich history. Metzger (1961) assessed the potential water supply in Grand Canyon National Park. Huntoon (1974, 1982) described surface water and groundwater flow of the North and South Rims of Grand Canyon and presented analysis of karst flow in the system. Foust and Hoppe (1985) and Goings (1985) established seasonal trends and baseline values for major and trace dissolved constituents in spring waters. Zukosky (1995) contributed stable isotopic (ẟ2H and ẟ18O) and rare earth element analysis. Fitzgerald (1996) contributed tritium and uranium isotope analysis to the spring data set. Ingraham et al. (2001) explored the possibility of using stable isotopes as a tracer for anthropogenic influence at Indian Garden Spring, and Liebe (2003) focused on uranium and uranium isotopes. Monroe et al. (2005) comprehensively explored the hydrogeochemistry of springs discharging along the South Rim of Grand Canyon, adding radiocarbon, strontium isotopes, and an extensive trace element suite. Crossey et al. (2006) utilized noble gas and radiocarbon analysis to understand contribution from fluids lower in the earth’s crust. Bills et al. (2007) built upon the Monroe et al. (2005) study by resampling springs over time. Tobin et al. (2018) provided a review of all hydrogeologic and geochemical studies conducted on groundwater in Grand Canyon.

Breccia pipe deposits

Solution-collapse features known as breccia pipes are found throughout northern Arizona, South Dakota, Wyoming in the USA (Epstein 2005), and internationally with examples from Canada (Ford 1997), Australia (Feltrin and Oliver 2014), Spain (Gutiérrez et al. 2001), China (Yaoru et al. 2002), and Lithuania and England (UK) (Friedman 1997). Breccia pipes in the Grand Canyon region are thought to form by dissolution and karst development in the underlying Redwall Limestone unit, with progressive collapse moving upwards through time into overlying rock units, forming a rubble (breccia) filled column that can be as much as 3,000 ft (~915 m) or more in height (Alpine and Brown 2010; Fig. 3). Breccia pipes are roughly circular in plan view, about 300 ft (~90 m) in diameter, and are often characterized by inward dipping beds along the margins (Otton and Van Gosen 2010). Other collapse features found throughout the Grand Canyon region include sinkholes and localized shallow collapse caused by dissolution of gypsum in the Kaibab and Toroweap formations (Billingsley et al. 2008). In the absence of breccia exposed at the surface, the most effective way to determine if a breccia pipe underlies a collapse feature is by obtaining a geologic core from drilling.

Stratigraphic section of the Grand Canyon sedimentary sequence showing a breccia pipe, with mineralization in the shaded section in the middle of the pipe; modified from Van Gosen and Weinrich 1989. 1 foot = 0.3048 m

Some breccia pipes contain concentrated deposits of uranium, copper, silver, lead, zinc, cobalt, and nickel minerals (Wenrich 1985; Wenrich et al. 1989; Finch et al. 1992). Uranium mineralization in breccia pipes likely occurred in multiple stages as mineralizing fluids moved through the pipe. Initial reducing conditions within areas of the pipe led to reduction of oxidized uranium, U(VI), and formation of lower-solubility U(IV) minerals, such as uraninite. The dissolved uranium minerals were then deposited when a subsequent mineralizing fluid with differing characteristics moved through the pipe (Wenrich 1985; Huntoon 1996). High-grade uranium ore deposits are most commonly located in breccia adjacent to the Coconino Sandstone, Hermit Formation, and the upper members of the Supai Group (Otton and Van Gosen 2010).

Mining of breccia-pipe-ore zones for copper, lead, zinc, and silver in the Grand Canyon region began in the 1860s, with uranium mining beginning in the 1950s. One of the early mines in the region was the Orphan Lode Mine (located at the head of the Horn Creek drainage and represented by the red diamond south of site 10 on Fig. 1) which was originally developed as a copper mine in 1893. Uranium ore was discovered in the mine workings from the Orphan Lode Mine by the US Geological Survey (USGS) in 1951. The Orphan Mine produced 4.3 million pounds of uranium oxide from 1956 to 1969 and was the largest uranium producer in the region during the early 1950s and 1960s (Chenoweth 1986). The uranium deposits found at the Orphan Lode Mine led to the regional exploration for additional uranium mineralized breccia pipe deposits.

Methods

Data collection

Water samples collected for this study from two wells and 12 spring sites between September 2016 and May 2018, are described in detail in the following. The analytical results were combined with reported data from Red Canyon, JT, Miners, Monument, Lonetree, and Salt Creek Springs (published in Monroe et al. 2005), Fossil Canyon, Matkatamiba, Ruby, Sapphire, Serpentine, and Slate Springs (from Bills et al. 2007), and Warm Springs and Bar 4 Well (USGS 2019; Fig. 1). All samples were collected by the USGS using standard field methods (USGS 2006; 2018), and filtered samples were passed through a 0.45-μm capsule filter. Detailed field and analytical descriptions are published in Beisner et al. (2017).

Field parameters including pH, water temperature, specific conductance, dissolved oxygen, and barometric pressure were measured on site just before water samples were collected. Spring samples were collected as close to the point of issuance from the ground as possible using a peristaltic pump with flexible silicon tubing. Wells were purged of three casing volumes and parameters were within stability criteria prior to collection of water samples (USGS 2006).

Water samples were analyzed for major, trace, and rare-earth elements by the USGS National Research Program Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado (USGSTMCO) using methods from Garbarino and Taylor (1996), (2001), and Garbarino and Taylor (1979). The precision for all methods analyzed by the USGSTMCO was 4% or better depending on the element. Nitrate (NO3) plus nitrite (NO2) was analyzed by colorimetry at the USGS National Water Quality Laboratory (Patton and Kryskalla 2011).

Strontium isotope ratios (87Sr/86Sr) were measured by the USGS National Research Program Laboratory in Menlo Park, California, using methods described in Bullen et al. (1996) with precision of ±0.00002 or better at the 95% confidence level. ALS Environmental in Fort Collins, Colorado, analyzed water samples for uranium isotopes (234U, 235U, and 238U) using alpha-counting methods (ASTM D 3972) as a USGS contract laboratory.

Quality assurance

One field blank and one replicate were analyzed along with the samples collected between 2016 and 2018. The field blank of certified inorganic-free blank water was collected at the Pipe Spring site in September 2016. A replicate sample was collected from Indian Garden Spring in September 2016. Multiple standard reference samples were analyzed by the USGSTMCO during every analytical run. A detailed analysis of the standard reference sample performance for the respective laboratories is presented in Beisner et al. (2017).

In the field blank from 2016 the following chemical analytes had a value above the reporting level concentration (in parentheses); aluminum (0.4 μg/L), nickel (0.06 μg/L), antimony (0.005 μg/L), tin (0.1 μg/L), and sulfate (0.02 mg/L). The measured concentrations in the blank for the aforementioned constituents were similar to concentrations in blanks collected by the same method reported in Beisner et al. (2017). For the majority of those analytes, the environmental sample values were more than 10 times greater than the blank concentrations and likely do not bias the environmental values. The aluminum value from the blank of 0.4 μg/L is similar to values from several samples and some environmental samples are below the threshold of 10 times the blank value for tin and antimony. The aforementioned blank was analyzed with a batch of nine other samples in the dataset. The reporting level from USGSTMCO changes between batch runs of samples.

The replicate sample from 2016 was within 1% of the associated environmental sample for major ions and the average of trace element difference was 5%. The following elements had greater than a 20% difference between the replicate and environmental samples (percent difference in parentheses); beryllium (22%), cadmium (22%), phosphorus (29%), and antimony (57%). A detailed analysis of replicate samples collected from north of Grand Canyon is presented in Beisner et al. (2017).

Data analysis

As the majority of trace elements had one or more values below a laboratory reporting level, with several elements containing multiple reporting levels, specific statistical methods (Helsel 2012) for data with values below a censoring threshold (laboratory reporting level) were used to analyze the majority of analytes presented in this study. Detailed description of the statistical tests is given in Beisner et al. (2017). A p-value threshold of 0.05 (95% confidence level) was used to indicate statistical significance for all mentioned statistical tests.

Robust regression on order statistics (ROS) using the cenros function from the NADA software package in R (R Core Team 2018; Lee 2017) was applied to chemical analysis from spring samples for each element to calculate the median, mean, and standard deviation of the data. Groundwater in this study was compared to groundwater north of Grand Canyon (Beisner et al. 2017), using the cendiff function from the NADA package in R (Lee 2017; Helsel and Lee 2006).

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed on the ranks of the uscores (Helsel 2012, 2016) using the metaMDS function from the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2016) using Euclidean distance and two dimensions. Zero dissimilarities were handled by adding a small positive value and no autotransform since there are no community data (Helsel 2012). The following analytes were included in the NMDS: As, B, Ba, Li, Mo, Rb, Se, SO4, Sr, U, V, and Zn; these were chosen based on interest for uranium mining in the region including groundwater north of Grand Canyon (from Beisner et al. 2017) and others that showed large variation across the study area (B, Ba, Rb, and SO4). NMDS stress values ≤0.1 are considered fair with good ordination and no real prospect of misleading interpretation, values ≤0.05 indicate good fit, and values ≥ 0.2 are deemed suspect (Clarke et al. 2014).

The analytes used in the NMDS analysis were evaluated for correlation by calculating Kendall’s Tau using the cenken function from the NADA package in R (Lee 2017). A cluster analysis was used to identify similar groups in the spring samples by evaluating minimum differences within groups and maximum differences among groups using the hclust function for the analytes used in the NMDS analysis. The Calinski-Harabasz criterion was used to determine the number of clusters that maximizes the difference between clusters, while minimizing the differences within clusters with the cascadeKM function of the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2016).

PHREEQCI version 3.5.0 (Charlton and Parkhurst 2002; Parkhurst and Appelo 2013) was used to determine saturation indices of calcite, dolomite, and gypsum. The WATEQ4F database was used with the default redox potential (pe) value of 4, since none of the water samples indicate reducing conditions.

Results

Parameters and major ions

Groundwater temperature ranged from 9 to 26.5 °C with a median temperature of 18.3 °C. pH ranged from 6.4 to 8.8 with a median of 7.4. Specific conductance ranged from 293 to 4,890 uS/cm with a median of 604 uS/cm. Dissolved oxygen ranged from 3 to 11.4 mg/L in the data set, except for Bar 4 Well which had the lowest dissolved oxygen value (0.7 mg/L), with a median dissolved oxygen of 7.2 mg/L.

The majority of sites can be classified as having calcium-magnesium-bicarbonate type water. Except for Blue Spring, which was dominated by sodium type water, the major cations were calcium and magnesium. For the major anions, the majority of sites were dominated by bicarbonate. Some springs were a mixture of bicarbonate-sulfate (Lonetree, Horn, Salt Creek, Slate, Sapphire, Serpentine, Royal Arch, and 140 Mile Springs). Sulfate groundwaters were generally located on the west side of the study area and include Ruby, Fossil Canyon, Matkatamiba, Bar 4 Well, and National Canyon Springs. Blue Spring was dominantly chloride type water (Fig. 4).

Nitrate ranged from <0.002 to 1.4 mg/L as N, with a median value of 0.51 mg/L as N. All sample concentrations of nitrate were below the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) drinking water maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 10 mg/L (USEPA 2019) except for one elevated value at Monument Spring. This outlier was noted in Monroe et al. 2005 as possibly influenced by wastewater effluent from the South Rim of Grand Canyon or by exposure to geologic features not encountered by water discharging at other springs.

Trace elements

Some groundwater sample concentrations in this study exceeded the USEPA drinking water standards for As and U (Table 1; USEPA 2019). Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu, and Warm Springs waters exceeded the USEPA drinking water standard for As of 10 μg/L (Fig. 5a), and Salt Creek Spring water exceeded the USEPA drinking water standard for U of 30 μg/L (Fig. 5b).

Median and mean trace element concentrations for all 27 groundwater sites south of Grand Canyon in this study (25 springs and 2 wells; Supai Well No. 3 not included as it is primarily supplied by water from Havasu Spring) are listed in Table 1. Some elements were not statistically quantified due to the following reasons: the majority of the sample concentrations were below the censoring threshold from blanks in Beisner et al. 2017 (Al, Be, Cd, Cu, Mn, Pb, Sb, and Zn), more than 80% of the sample concentrations were below the highest laboratory reporting level (Co and Fe), or more than 60% of the sample concentrations were below the laboratory reporting level (Ni).

Eleven sites (Blue, JT, Miners, Grapevine, Pipe, Canyon Mine Well, Horn, Salt Creek, Hermit, East Boucher, and National Canyon Springs) had three or more samples over time reported in Monroe et al. 2005, Bills et al. 2007, and USGS 2019. Change of uranium concentration over time at these sites was small, varying between 10 and 30%. There are not enough data to statistically analyze trends over time, but clear monotonic trends are not obvious. Monroe et al. (2005) sampled the majority of the springs presented in this report during different times of the year and found that there was temporal consistency of chemical results for individual springs. Generally, springs discharging south of Grand Canyon presented in this report show less temporal variability than springs north of Grand Canyon on the margins of the Kaibab Plateau that show rapid response from seasonal recharge pulses (Jones et al. 2017; Tobin et al. 2018).

Radioisotopes

Uranium isotopes

Natural uranium consists of three isotopes 238U, 235U, and 234U with relative abundances of approximately 99.27%, 0.72%, and 0.0057%, respectively. The ratio 234U/238U can vary widely in natural waters, as a result of processes such as alpha recoil, which allows for preferential mobility of 234U relative to 238U during interactions between water and solid phases (Faure and Mensing 2005). Uranium in undisturbed rocks and minerals older than approximately 1 million years reaches a state of radioactive equilibrium where the rate of decay of the short-lived 234U is limited by the rate of decay of the long-lived 238U parent. As a result, the 234U/238U activity ratio (UAR) is expected to equal unity (defined as secular equilibrium or UAR = 1.0). Water in contact with high-grade uranium ore having a recent history of oxidation and leaching is likely to represent a mixture of material with UARs both greater than and less than 1.0. Typical values for natural groundwaters fall in the 1–3 range but values in excess of 10 are possible (Kronfeld 1974; Osmond and Cowart 1976; Szabo 1982).

The UAR values of groundwater samples from this study generally decreased with increasing uranium concentrations (Fig. 6). The lowest UAR values were from Horn Creek and 140 Mile Springs (1.25 and 1.30 respectively), although the low uranium concentration (less than 10 μg/L) may reflect interaction with a nearby source of uranium that has undergone chemical change or mixing with other waters before discharging at the spring. Salt Creek Spring had the highest uranium value (31 μg/L) from this study and had a correspondingly low UAR of 1.55. The Canyon Mine Well is drilled into the Muav Limestone next to a mineralized breccia pipe deposit and had the second highest uranium value (13 μg/L) and a moderately low UAR (2.1). The mineralized zone of the Canyon Mine breccia pipe occurs in the Coconino Sandstone through the Supai Group, stratigraphically above the screened interval of the Canyon Mine Well.

JT and Miners Springs had low UAR values (1.78 and 1.49, respectively) but low uranium concentration (4.1 and 3.1 μg/L, respectively). The abandoned Grandview Mine (Fig. 1), which was a mineralized breccia pipe mine, is located near Miners Spring and more investigation of water upgradient of the spring emergence would provide additional context for these low UAR values. These two springs have tritium concentrations indicating a possible mixture of modern and premodern waters (Solder et al. 2020).

The ratio of 87Sr to 86Sr (87Sr/86Sr) can provide an indication of water–rock interaction as groundwater moves through the subsurface. Precambrian basement rocks of the region have the most radiogenic (highest) strontium isotopic ratios (greater than 0.714; Crossey et al. 2006, Patchett and Spencer 2001, Johnson et al. 2011, Bills et al. 2007), Tertiary volcanic rocks have the lowest strontium isotopic ratios (0.70463–0.70535; Bills et al. 2007), and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks have intermediate strontium isotopic ratios (0.70756–0.71216; Monroe et al. 2005 and Bills et al. 2007) as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Strontium isotopic ratio (87Sr/86Sr) versus strontium concentration for groundwater samples. The range of strontium isotopic ratio in Paleozoic sedimentary rocks is presented as bars to the right of the graph, including the number of samples for each rock unit from Monroe et al. 2005 and Bills et al. 2007

Generally, groundwater samples with a higher strontium concentration had a lower strontium isotopic ratio (Fig. 7). Samples from Matkatamiba, National Canyon Springs, and Bar 4 Well had the highest strontium concentrations (2,400–2,805 μg/L) and the lowest strontium isotopic ratios (0.707853–0.70819) near the average values of the Kaibab and Toroweap Formations. The highest strontium isotopic ratio values were associated with some of the lowest strontium concentrations in this dataset, some of which (JT, Lonetree, Pipe, Horn, Salt Creek, and Serpentine Springs) are greater than the highest strontium isotopic ratio values from sedimentary rocks from the Grand Canyon (0.71216; Monroe et al. 2005 and Bills et al. 2007). Strontium isotopic values (87Sr/86Sr) are not available for Fossil Canyon, Ruby, Sapphire, Slate, and Warm Springs.

The springs with low strontium concentrations may indicate less water rock interaction and may be influenced by strontium isotopic ratios of dissolved minerals different than the bulk sedimentary rock values from Monroe et al. 2005 and Bills et al. 2007. Of note, the only spring north of the Grand Canyon with a high strontium isotopic ratio and strontium concentration (Fence Spring; 0.71417, 1060 ug/L, respectively) had a distinct chemical signature of geothermal fluids (Crossey et al. 2006; Beisner et al. 2017).

Discussion

Spatial geochemical signatures

The groundwater north of Grand Canyon is physically isolated from the groundwater to the south as the stratigraphic units are cut through by the Colorado River. Baseline and anomalous concentrations for groundwater north of Grand Canyon, assessed for 36 spring samples from the Toroweap Formation to the Redwall Limestone (Beisner et al. 2017), were compared to 27 groundwater samples collected south of Grand Canyon from this study, to assess regional similarities for select elements (As, B, Li, Se, Sr, Tl, U, V).

As and Sr were significantly different between the north and south groups (p <0.05). As values were higher and Sr values were lower in the group of springs south of Grand Canyon compared with the group of springs north of Grand Canyon. Elevated As concentrations may be related to the volcanic rocks present near the recharge source for water on the South Rim of Grand Canyon (Fig. 2), that are not a present in the presumed recharge area for springs north of Grand Canyon (Beisner et al. 2017). Strontium concentrations generally increase with sulfate concentration and may suggest that water in contact with gypsum along its flow path has elevated strontium. Groundwaters north of Grand Canyon include groundwater discharging from stratigraphic units including and above the Redwall Limestone, which show geochemical evidence of interaction with gypsum units in the Toroweap Formation (Beisner et al. 2017). The other elements (B, Li, Se, Tl, U, and V) were not statistically different between the north and south groups.

Five springs in this study (Pipe, Horn, Indian Gardens, National Canyon, and 140 Mile) discharge from alluvial material rather than directly from bedrock. Changes in trace element chemistry in Horn Creek as water discharges from bedrock and moves through alluvial material have been observed (Beisner and Tillman 2019). Water at the head of the eastern fork of the Horn Creek drainage emerges from bedrock with elevated uranium concentration (257 μg/L), low UAR (1.12), calcium-magnesium-sulfate type water, and low tritium (0.9 pCi/L), then infiltrates into the alluvium and emerges lower in the drainage with lower uranium concentration (23 μg/L), similar UAR (0.95), calcium-magnesium-bicarbonate type water, and elevated tritium (2.6 pCi/L; Beisner and Tillman 2019). Monroe et al. 2005 similarly discussed changes in chemical constituent concentration as groundwater discharging at a higher elevation in Cottonwood and Monument Creek drainages moves through alluvial material, noting increasing concentration of several major ions and decreases of several trace elements and nutrients. Unfortunately, blank and replicate samples were not assessed in the Monroe et al. 2005 study, which limits quantitative assessment of some of the elements from the chemical comparison along a drainage, but similar trends as those observed in Horn Creek by Beisner and Tillman (2019) suggest that additional chemical changes within the drainages are taking place. The mechanisms for the chemical changes within the drainages are not well understood and could vary depending on the local condition and possibly be influenced by mixing with another source of groundwater or geochemical changes as the water moves through unconsolidated material. However, the overall significance is that springs discharging from alluvial material may not have the same chemical signature of the bedrock groundwater, and characterizing secondary processes is critical for understanding Grand Canyon spring discharge chemistry.

Multivariate trace element analysis

Multivariate statistical analysis of groundwater south of Grand Canyon shows a good ordination distinction between sites based on their elemental assemblage (Fig. 8). Analytes associated near uranium in the NMDS were Mo, SO4, Se, and Sr (Fig. 8). These same analytes were related to U with a significant positive Kendall’s Tau value (Fig. 9). Uranium had a significantly negative Kendall’s Tau relationship with Ba and As (indicating that higher values of uranium are associated with lower values of Ba and As), which are located across the NMDS plot from uranium (Fig. 8).

A cluster analysis on the data used in the NMDS analysis using the Calinski-Harabasz criterion indicates that there are three distinct groups of groundwater sites (Fig. 10, and dashed outlines on Fig. 8). Blue, Havasu, Fern, and Warm Springs are in one group and have higher values of B, Li, Rb, and V and lower values of Mo and Se compared to other sites. Lonetree, Horn, Salt Creek, Slate, Sapphire, Ruby, Serpentine, Royal Arch, Fossil Canyon, 140 Mile, Matkatamiba, Bar 4 Well, and National Canyon Spring form another group and are distinguished by higher values of Mo, Se, SO4, and Sr and lower values of Ba. Red Canyon, JT, Miners, Grapevine, Pipe, Indian Gardens, Monument, Hermit, East Boucher Springs and Canyon Mine Well form another group and are distinguished by lower values of B, Li, SO4, and Sr. The groundwater site groupings appear to overlap spatially from east to west with clustering of sites locally (Fig. 10).

Groundwater geochemical evolution

Multiple geochemical tracers were used to understand recharge source, groundwater residence time, and water–rock interaction of groundwaters analyzed in this study. A companion paper (Solder et al. 2020) and USGS (2019) present environmental-age tracer analysis for groundwaters presented in this report. Groundwater-age tracer analysis is combined with geochemical information and discussed in the following paragraphs. Detailed geochemical modeling was not performed for this study, as there were not enough samples along a flow path from recharge source to discharge available for the study area.

Using the categorical age classification for tritium of <1.3 pCi/L for premodern water, >12.8 pCi/L for modern water, and values between for a mixture of premodern and modern water from Beisner et al. (2017), no samples contained primarily modern water (water recharged after 1952) and the majority of the sites had a mixture of modern and premodern water and some sites were predominantly premodern water (Blue, Havasu, Supai Well No. 3, Fern, Boucher East, Canyon Mine Well, Hermit, Pipe, Indian Gardens Spring, and Bar 4 Well; Bills et al. 2007, Monroe et al. 2005, Solder et al. 2020). Tritium values were not available for Fossil Canyon, Ruby, Sapphire, Slate and Warm Springs (Bills et al. 2007). Spring sites with sulfate or sulfate/ bicarbonate water had tritium in the range of a mixture of modern and premodern water and may indicate a component of water that potentially moved through the subsurface gypsum deposits along a shorter flow path. Bar 4 Well did have sulfate water type but no measurable tritium (Bills et al. 2007; USGS 2019).

Solder et al. (2020) calculated mean age for the springs sampled between 2016 and 2018 for this study as well as for groundwater data published in Monroe et al. 2005 and Bills et al. 2007. Sites classified as premodern water had mean ages ranging from approximately 1,050 to 19,200 years. Of the premodern samples, Pipe Spring had the lowest mean age of 1,050 years and the next lowest age was Indian Gardens Spring with 2,750 years. Tritium content was 3.5 pCi/L in Pipe Spring samples collected in 2000 (Monroe et al. 2005), which would indicate a mixture of modern and premodern water and may explain the low mean age compared with other springs with low tritium values. Waters with tritium concentrations indicating a mixture of modern and premodern water had lower mean age ranging from 90 to 2,900 years. Monument Spring had the highest mean age for the mixed waters of 2,900 years (Monument Spring tritium value was 1.3 pCi/L, which is right at the threshold for premodern water) and the next highest age was Royal Arch Spring with a mean age of 2,400 years.

Dedolomitization may be occurring in some groundwater south of Grand Canyon, and may affect the radiocarbon age calculation (Plummer et al. 1990; Fitzgerald 1996). The calculated saturation index of gypsum was negative for all samples in this study, but values show a logarithmic increase to near saturation with increasing sulfate concentration (Fig. 11). Samples range from Grapevine Spring with 6 mg/L sulfate and SI of gypsum of –3.03 to National Canyon Spring with 991 mg/L sulfate and SI of gypsum of –0.42 (Fig. 11). Five sites (National Canyon, Matkatamiba, Ruby, Fossil Springs, and Bar 4 Well) had high sulfate concentration (>600 mg/L), saturation indices (SI) of gypsum less than 0.7, calcite SI plus or minus 0.25, and dolomite SI plus or minus 0.5, which may indicate dedolomitization

Saturation indices of a gypsum and b dolomite for groundwater samples south of Grand Canyon. Samples are represented by purple squares. Respective site numbers are presented in Fig 1

Four springs (Blue, Havasu, Fern, and Warm Spring) had unique chemistry and may represent a contribution of groundwater from deeper in the earth’s crust (Crossey et al. 2006) or long groundwater residence times. These sites are located at discrete locations in the study area near major structural geologic features that may allow for focused groundwater discharge and may also provide a pathway for interaction with deep crustal materials. Characteristics of these waters are premodern tritium values, radiocarbon ages on the order of 4,000–16,000 years (Solder et al. 2020), elevated As, B, Li, Rb, and V concentration, calcium-magnesium-bicarbonate type water (except for Blue Spring with sodium-chloride type water), and intermediate UAR (between 2 and 3)—see Table S1 of the electronic supplementary material (ESM). Strontium isotopic ratio was intermediate for these springs (Table S1 of the ESM), suggesting groundwater chemistry is largely controlled by interaction with Paleozoic carbonate rocks rather than Precambrian basement rocks with more radiogenic strontium isotopic ratios (Crossey et al. 2006).

Groundwaters with a dominant sulfate type water (Slate, Sapphire, Ruby, Fossil Canyon, Matkatamiba, Bar 4 Well, and National Canyon Spring) are located on the western side of the study area (orange group on multivariate analysis on Fig. 10). Gypsum deposits grade thicker from east to west in the study area (Billingsley et al. 2008; P. Huntoon, University of Wyoming, personal communication, 2019) and may explain the predominance of sulfate type water of samples in the west part of the study area (Fig. 4). Three of these sites have strontium isotopic data (National Canyon, Matkatamiba Springs, and Bar 4 Well), which indicate high strontium concentration and low strontium isotopic ratio that may indicate interaction with gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) deposits in the Kaibab and or Toroweap formations (Fig. 7). Ruby and Fossil Canyon Springs have elevated strontium concentrations (1,900 and 2,300 μg/L, respectively; Table S1 of the ESM), and may also have low strontium isotopic ratio which warrants follow up sampling. Matkatamiba and National Canyon Springs have tritium indicating a mixture of modern and premodern water (Table S1 of the ESM; Solder et al. 2020). National Canyon had a young mean age of 87 years and Matkatamiba had an intermediate age of 1,200 years. Bar 4 Well had no measurable tritium and an old radiocarbon age of 19,100 years, although the age may be less if dedolomitization is occurring along the flow path before the Bar 4 Well (Solder et al. 2020).

Other sites with a mixture of bicarbonate and sulfate type waters (Lonetree, Horn, Salt Creek, Serpentine, Royal Arch, and 140 Mile Springs; Fig. 4) are also part of the orange multivariate group (Fig. 10) and have tritium values indicating a mixture of modern and premodern water, low UAR (no data for Lonetree and Serpentine), and high strontium isotopic ratios (except Royal Arch Spring; Figs. 6 and 7). Lonetree, Horn, Salt Creek, and 140 Mile Spring water samples had low radiocarbon ages ranging from 175 to 1,000 years. Serpentine and Royal Arch Springs waters had older radiocarbon ages ranging from 2,000 to 2,400 years (Solder et al. 2020). Horn and 140 Mile Springs waters had the lowest UAR values from the study (Fig. 6) and had low radiocarbon ages of 360 and 175 years respectively (Solder et al. 2020).

The other springs in the study area (Red Canyon, JT, Miners, Grapevine, Pipe, Canyon Mine Well, Indian Gardens, Monument, Hermit, and East Boucher) had calcium-magnesium-bicarbonate type waters (green group from multivariate analysis in Fig. 10). The spring waters from this group on the east side of the study area (Red Canyon, JT, Miners and Grapevine Springs) have tritium indicating a mixture of modern and premodern waters and radiocarbon ages ranging from 345 to 1,500 years (Solder et al. 2020), high strontium isotopic ratio, high As and low U concentration (Table S1 of the ESM). Other lines of evidence, including groundwater flow modeling (Knight and Pool 2016) and isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen in water (Solder and Beisner 2020), suggest water present at the aforementioned springs has a short flow path and may have a more local source of recharge compared to the regional system. The groundwater from sites located to the west of the aforementioned springs generally have tritium indicating primarily premodern water and radiocarbon ages ranging from 1,050 to 12,000 years (except for Pipe and Monument spring as discussed at the beginning of this section; Solder et al. 2020).

Generally, the majority of water in this study area recharges the subsurface near the San Francisco Peaks and migrates down through permeable structural features to the Redwall-Muav aquifer (Fig. 2), consistent with previous conceptual models of groundwater flow (e.g., Hart et al. 2002; Monroe et al. 2005, Bills et al. 2007). Multiple independent geochemical constituents, as reported in this study and two companion papers (Solder et al. 2020; Solder and Beisner 2020), show additional sources of local recharge to the subsurface located north of the San Francisco Peaks along the Coconino Plateau. Locally, groundwater migrates from upper stratigraphic units containing gypsum to the Redwall-Muav aquifer through permeable structural features. In some parts of the study area, large-scale structural features such as faults, facilitate transport of older groundwater from the deep subsurface. The exchange between the shallow meteoric and deep subsurface groundwater flow systems along large structural features is apparent in the tracer chemistry (Solder et al. 2020; Solder and Beisner 2020), trace element chemistry (Fig. 11), and abundant dissolved carbon dioxide as reported by Crossey et al. (2006) and observed as over saturation and deposition of carbonate mineral species. Conversely, small-scale groundwater interaction with mineralized breccia pipes in the region is not well understood. The observed chemical anomalies that occur around known mineralized breccia pipes are the subject of further research.

Conclusions

The objectives of this study were to characterize the geochemical signatures of groundwater south of Grand Canyon, establish baseline concentrations for select trace elements, and identify anomalous groundwater chemistries. Better understanding of the geochemical evolution of groundwater south of Grand Canyon is needed to understand potential effects from breccia-pipe uranium mining in the region.

Groundwater from 28 sampling locations south of Grand Canyon were analyzed for major ion, trace element, and radioisotopic constituents. Groundwater south of Grand Canyon was not statistically different from water north of Grand Canyon (from Beisner et al. 2017) for the following elements B, Li, Se, Tl, U, and V; however, As was higher in the southern groundwater and Sr was lower. Five groundwater sites (Red Canyon, Miners, JT, Havasu, and Warm Springs) exceeded the USEPA drinking water standard for As of 10 μg/L. Salt Creek Spring exceeded the USEPA drinking water standard for U of 30 μg/L.

Four springs from the study area (Blue, Havasu, Fern, and Warm Springs) had unique chemistry, which may indicate a deep flow path or potential contribution of fluids from lower in the crust. The other springs in the study area were distinguished by major anion water type, sulfate, bicarbonate and a mixture of sulfate and bicarbonate. Water type distinctions were somewhat spatially segregated with sulfate type groundwater present on the western side of the study area where there are thicker gypsum deposits (Billingsley et al. 2008; P. Huntoon, University of Wyoming, personal communication, 2019), bicarbonate type groundwater on the eastern side of the study area, and a mixture of the two interspersed between the endmember sites. Sulfate type groundwater from this study has low strontium isotopic ratio (87Sr/86Sr) values in the range of rock values from the gypsum containing Kaibab and Toroweap formations. The water with high sulfate had higher tritium values indicating a component of younger water that may have moved from high in the stratigraphic section down to the Redwall-Muav aquifer along a focused preferential pathway (potential structurally enhanced conduit).

The location of spring groundwater sample collection within drainages of the Grand Canyon is important, and changes in chemistry may occur as groundwater discharges from bedrock and flows through alluvial material. The eastern fork of the Horn Creek drainage represents an area with groundwater discharging from bedrock high in the drainage that infiltrates into the alluvium and resurfaces lower in the drainage. The UAR is similar for the water with high uranium concentration at the head of the drainage, as it is for the groundwater emerging from the alluvium included in this study (Liebe 2003; Beisner and Tillman 2019). However, the tritium concentration is low for the water emerging from the Redwall Limestone at the head of the drainage (0.9 pCi/L) and increases to 3.4 pCi/L at the site in the alluvium described in this study, which may indicate mixing with a component of modern water in the alluvium (Beisner and Tillman 2019; USGS 2019). The UAR is generally insensitive to mixing with water that has low uranium concentration, such as precipitation recharging near the alluvium, whereas mixing with other regional groundwater with dissolved uranium and higher UAR would tend to drive the UAR value up in the mixed water.

Repeat sampling at shorter timescales would also be beneficial, especially at sites with a potential component of modern water, as changes in elemental concentration and tritium have been observed over monthly timeframes in groundwater at Pigeon Spring north of Grand Canyon (Beisner and Tillman 2018). Monument Spring has not been sampled since 2001 (Monroe et al. 2005) and resampling would lead to a better understanding of elevated nitrate concentrations and geochemical changes over time. Resampling at Slate, Sapphire, Ruby, Fossil Canyon, and Warm Spring would provide a comprehensive geochemical suite.

A conceptual understanding of the system indicates that the majority of water in this study area recharges the subsurface near the San Francisco Peaks and migrates down through permeable structural features to the Redwall-Muav aquifer. Additional sources of recharge from lower-elevation locations closer to Grand Canyon migrate from upper stratigraphic units containing gypsum to the Redwall-Muav aquifer through permeable structural features. Large structural features are present where older groundwater with no component of modern water and potential interaction with deeply sourced fluids discharges from the subsurface. Chemical anomalies occur around known mineralized breccia pipes and are the subject of further research.

References

Alpine AE (ed) (2010) Hydrological, geological, and biological site characterization of breccia pipe uranium deposits in northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2010–5025, 354 pp. Also available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5025/. Accessed June 2020

Alpine AE, Brown KM (2010) Introduction. In: Alpine AE (ed) Hydrological, geological, and biological sites characterization of breccia pipe uranium deposits in northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2010–5025, 17 pp. Also available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5025/. Accessed June 2020

Beisner KR, Tillman FD (2018) Assessing temporal changes in geochemistry at spring sites located in an area of breccia pipe uranium deposits. Geological Society of America Joint Rocky Mountain and Cordilleran Section Meeting Abstracts with Programs Flagstaff, Arizona vol 50, no. 5. https://doi.org/10.1130/abs/2018RM-314266

Beisner KR, Tillman FD (2019) Assessing spatial differences in uranium concentrations in groundwater along the Horn Creek drainage in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. 11th National Monitoring Conference abstract with program, Denver, CO, March 25–29, 2019

Beisner KR, Tillman FD, Anderson JR, Antweiler RC, Bills DJ (2017) Geochemical characterization of groundwater discharging from springs north of the Grand Canyon, Arizona, 2009–2016. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2017–5068, 58 pp. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175068

Billingsley GH (2000) Geologic map of the Grand Canyon 30′ × 60′ quadrangle, Coconino and Mohave counties, northwestern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Geol Invest Ser I-2688

Billingsley GH, Felger TJ, Priest SS (2006) Geologic map of the Valle 30′ × 60′ quadrangle, Coconino County, northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Map 2895

Billingsley GH, Priest SS, Felger TJ (2008) Geologic map of the Fredonia 30′ × 60′ quadrangle, Mohave and Coconino counties, northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Map 3035, scale 1;100,000

Bills DJ, Flynn ME, Monroe SA (2007) Hydrogeology of the Coconino Plateau and adjacent areas, Coconino and Yavapai counties, Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2005–5222, version 1.1, 101 pp, 4 plates. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20055222v1.1

Brown NA, Mead RH, McMurray JM (1992) Relationship between collapse history and ore distribution in the Sage Breccia Pipe, northwestern Arizona. In: Dickinson KA (ed) Short papers of the U.S. Geological Survey Uranium Workshop, 1990. US Geol Surv Circ 1069:54–56

Bullen TD, Krabbenhoft D, Kendall C (1996) Kinetic and mineralogic controls on the evolution of groundwater chemistry and 87Sr/86Sr in a sandy silicate aquifer, northern, Wisconsin. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 60(10):1807–1821

Charlton SR, Parkhurst DL (2002) PHREEQCI-A graphical user interface to the geochemical model. US Geol Surv Fact Sheet PHREEQC FS-031-02

Chenoweth WL (1986) The Orphan Lode Mine, Grand Canyon, Arizona: a case history of a mineralized, collapse-breccia pipe. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 86-510, 90 pp

Clarke KR, Gorley RN, Somerfield PJ, Warwick RM (2014) Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation, 3rd edn. PRIMER-E: Plymouth, chap 5, PRIMER-E, Auckland, New Zealand, pp 5–6

Crossey LJ, Fischer TP, Patchett PJ, Karlstrom KE, Hilton DR, Newell DL, Huntoon P, Reynolds AC, Leeuw GAM (2006) Dissected hydrologic system at the Grand Canyon: interaction between deeply derived fluids and plateau aquifer waters in modern springs and travertine. Geology 34(1):25–28. https://doi.org/10.1130/G22057.1

Crossey LJ, Karlstrom KE, Springer AE, Newell D, Hilton DR, Fischer T (2009) Degassing of mantle derived CO2 and He from springs in the southern Colorado Plateau region: neotectonic connections and implications for groundwater systems. GSA Bull 121(7–8):1034–1053. https://doi.org/10.1130/B26394.1.

Epstein, JB (2005) National evaporite karst-some western examples. In: Kuniansky EL (ed) U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, Rapid City, SD, September 12–15, 2005. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2005-5160, Part2_4B

Faure G, Mensing TM (2005) Isotopes: principles and applications, 3rd edn. Wiley, Hobokon, NJ, 928 pp

Feltrin L, Oliver NHS (2014) Timing and origin of megabreccia and folds along the Early Middle Cambrian margin of the Georgina Basin, Australia. Carbonates Evaporites 29:3–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13146-014-0193-6

Finch WI, Sutphin HB, Pierson CT, McCammon RB, Wenrich KJ (1990) The 1987 estimate of undiscovered uranium endowment in solution-collapse breccia pipes in the Grand Canyon region of northern Arizona and adjacent Utah. US Geol Surv Circ 1051, 19 pp

Finch WI, Pierson CT, Sutphin HB, (1992) Grade and tonnage model of solution collapse breccia pipe uranium deposits. In: Bliss JD (ed) Developments in mineral deposit modeling. US Geol Surv Bull 2004, pp 36–38

Fitzgerald J (1996) Residence time of groundwater issuing from the South Rim aquifer in the eastern Grand Canyon. MSc Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, 103 p

Ford DC (1997) Principal features of evaporite karst in Canada. Carbonates Evaporites 12:15–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03175798

Foust RD, Hoppe S (1985) Seasonal trends in the chemical composition of Grand Canyon Waters. Report prepared for US National Park Service, Ralph M. Bilby Research Ctr., University of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ, pp 30–35

Friedman GM (1997) Dissolution-collapse breccias and paleokarst resulting from dissolution of evaporite rocks, especially sulfates. Carbonates Evaporites 12:53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03175802

Garbarino JR, Taylor HE (1979) An inductively-coupled plasma atomic-emission spectrometric method for routine water quality testing. Appl Spectrosc 33:220–226

Garbarino JR, Taylor HE (1996) Inductively-coupled plasma-mass spectrometric method for the determination of dissolved trace elements in natural water. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 94-358, 49 pp

Gardner KS (1998) Formation of the Sage breccia pipe by solution and collapse processes, Coconino County, Arizona. University Park, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, 273 pp

Goings DB (1985) Spring flow in a portion of Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. MSc Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV

Gutiérrez F, Ortí F, Gutiérrez M, Pérez-González A, Benito G, Gracia Prieto J (2001) Durán Valsero JJ (2001) The stratigraphical record and activity of evaporite dissolution subsidence in Spain. Carbonates Evaporites 16:46. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03176226

Helsel DR (2012) Statistics for censored environmental data using Minitab® and R, 2nd edn. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 324 p

Helsel DR (2016) Calculating Uscores in R: practical stats web page. http://www.practicalstats.com/nada/downloads_files/. Accessed January 9, 2017

Helsel D, Lee LR (2006) Analysis of environmental data with nondetects: statistical methods for censored environmental data—continuing education workshop at the Joint Statistical Meetings American Statistical Association, Seattle, WA, August 6–10, 2006

Huntoon PW (1974) The karstic groundwater basins of the Kaibab Plateau, Arizona. Water Resour Res 10(3):579–590

Huntoon PW (1982) The ground-water systems that drain to the Grand Canyon of Arizona. Department of Geology and Water Resources Institute, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, pp 1–25

Huntoon PW (1996) Large-basin ground water circulation and paleo-reconstruction of circulation leading to uranium mineralization in Grand Canyon Breccia Pipes, Arizona. The Mountain Geologist 33(3):71–84

Ingraham NL, Zukosky K, Kreamer DK (2001) Application of stable isotopes to identify problems in large-scale water transfer in Grand Canyon National Park. Environ Sci Technol 35:1299–1302

Johnson RH, DeWitt E, Wirt L, Arnold LR, Horton JD (2011) Water and rock geochemistry, geologic cross sections, geochemical modeling, and groundwater flow modeling for identifying the source of groundwater to Montezuma Well, a natural spring in central Arizona. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 2011–1063, 62 pp

Jones CJR, Springer AE, Tobin BW, Zappitello SJ, Jones NA (2017) Characterization and hydraulic behaviour of the complex karst of the Kaibab Plateau and Grand Canyon National Park, USA. Geol Soc London Spec Publ 466:237–260. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP466.5

Knight J, Pool, D (2016) Simulating influence of geologic structures on regional groundwater flow in northern Arizona. Arizona Hydrological Society 29th annual symposium, Tucson, AZ, September 14–17, 2016

Kronfeld J (1974) Uranium deposition and Th-234 alpha recoil: an explanation for extreme U-234/U-238 fractionation within the Trinity aquifer. Earth Planet Sci Lett 21:327–330

Lee L (2017) Package ‘NADA’, nondetects and data analysis for environmental data, version 1.6-1: The Comprehensive R Archive Network web page. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/NADA/NADA.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2019

Liebe D (2003) The use of the 234U/238U activity ratio at the characterization of springs and surface streams in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Hochschule fur Technik und Wirtschaft Dresden, Germany, MSc Thesis, 105 pp

Mazeika CP (2002) Lithogeochemical characterization of the Sage Breccia Pipe, Coconino County, Arizona. Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, MSc Thesis, 303 pp

Metzger D (1961) Geology in relation to availability of water along the South-Rim, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. US Geol Surv Water Suppl Pap 1475-C:100–130

Monroe SA, Antweiler RC, Hart RJ, Taylor HE, Margot T, Rihs JR, Felger TJ (2005) Chemical characteristics of ground-water discharge along the South Rim of Grand Canyon in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 2000–2001. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2004-5146, 59 pp

Oksanen J, Guillaume Blanchet F, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Henry M, Stevens H, Szoecs E, Wagner H (2016) Package ‘vegan’: The Comprehensive R Archive Network web page. Community Ecology package, version 2.4-1., at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html. Accessed December 2016

Osmond JK, Cowart JB (1976) The theory and uses of natural uranium isotopic variations in hydrology. Int Atomic Energ Agency Atomic Energ Rev 14:620–679

Otton JK, Van Gosen BS (2010) Uranium resource availability in breccia pipes in northern Arizona. In: Alpine AE (ed) Hydrological, geological, and biological sites characterization of breccia pipe uranium deposits in northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Sci Invest Rep 2010–5025, pp 23–41. Also available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5025/. Accessed June 2020

Parkhurst DL, Appelo CAJ (2013) Description of input and examples for PHREEQC version 3: a computer program for speciation, batch-reaction, one-dimensional transport, and inverse geochemical calculations. US Geol Surv Tech Methods, book 6, chap A43, USGS, Reston, VA, 497 pp

Patchett PJ, Spencer JE (2001) Application of Sr isotopes to the hydrology of the Colorado River System waters and potentially related Neogene sedimentary formations. In: Young RA, Spamer EE (eds) Colorado River Origin and Evolution: Proceedings of a symposium held at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, June 2000, 280 pp

Patton CJ, Kryskalla JR (2011) Colorimetric determination of nitrate plus nitrite in water by enzymatic reduction, automated discrete analyzer methods. US Geol Surv Tech Methods, book 5, chap B8, 34 pp. Also available at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/tm/05b08/. Accessed June 2020

Plummer LN, Busby JF, Lee RW, Hanshaw BB (1990) Geochemical modeling of the Madison Aquifer in parts of Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota. Water Resour Res 26(9):1981–2014

R Core Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed June 2020

Solder JE, Beisner KR (2020) Critical evaluation of stable isotope mixing end-members for estimating groundwater recharge sources: case study from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, Arizona, USA. Hydrogeol J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02194-y

Solder JE, Beisner KR, Anderson, JR, Bills, D (2020) Rethinking groundwater flow on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, USA: characterizing recharge sources and flow paths with environmental tracers. Hydrogeol J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02193-z

Sutphin HB, Wenrich KJ (1989) Map of locations of collapse-breccia pipes in the Grand Canyon region of Arizona. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 89-550, 1 plate, scale 1:250,000

Szabo BJ (1982) Extreme fractionation of 234U/238U and 230Th/234U in spring waters, sediments, and fossils at the Pomme de Terre Valley, southwestern Missouri. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 46:1675–1679

Taylor HE (2001) Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Academic, New York, 294 pp

Tobin BW, Springer AE, Kreamer DK, Schenk E (2018) Review: The distribution, flow, and quality of Grand Canyon Springs, Arizona (USA). Hydrogeol J 26(3):721–732

Ulrich GE, Billingsley GH, Hereford R, Wolfe EW, Nealey LD, Sutton RL (1984) Map showing geology, structure, and uranium deposits of the Flagstaff 1 degrees × 2 degrees quadrangle, Arizona. US Geol Surv Miscel Invest Ser Map I-1446

US Department of the Interior (2012) Record of decision: northern Arizona withdrawal—Mohave and Coconino counties, Arizona. Bureau of Land Management web page. http://www.fwspubs.org/doi/suppl/10.3996/052014-JFWM-039/suppl_file/052014-jfwm-039r1-s08.pdf?code=ufws-site. Accessed June 2020

USEPA (2019) National primary drinking water regulations. https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations. Accessed February 4, 2019

US Geological Survey (2006) Collection of water samples (ver. 2.0). US Geol Surv Tech Water Resour Invest, book 9, chap A4. https://doi.org/10.3133/twri09A4. Accessed February 12, 2020

US Geological Survey (2018) General introduction for the “National field manual for the collection of water-quality data” (Ver. 1.1, June 2018). US Geol Surv Tech Water Resour Invest, book 9, chap A0. https://doi.org/10.3133/tm9A0. Accessed February 12, 2020

US Geological Survey (2019) National Water Information System. US Geological Survey web interface. https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P55KJN. Accessed February 4, 2019

Van Gosen BS, Wenrich KJ (1989) Ground magnetometer surveys over known and suspected breccia pipes on the Coconino Plateau, northwestern Arizona. US Geol Surv Bull 1683-C, 31 pp

Van Gosen BS, Wenrich KJ (1991) Geochemistry of soil samples from 50 solution-collapse features on the Coconino Plateau, northern Arizona. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 91-0594, 281 pp and 3 diskettes

Wenrich KJ (1992) Breccia pipes in the Red Butte area of Kaibab National Forest, Arizona. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 92-219-

Wenrich KJ (1985) Mineralization of breccia pipes in northern Arizona. Econ Geol 80:1722–1735

Wenrich KJ, Chenoweth WL, Finch WI, Scarborough RB (1989) Uranium in Arizona. In: Jenney JP, Reynolds SJ (eds) Geologic evolution of Arizona. Arizona Geol Soc Digest 17:759–794

Wenrich KJ, Aumente-Modreski RM (1994) Geochemical soil sampling for deeply buried mineralized breccia pipes, northwestern Arizona. Appl Geochem 9:431–454

Wenrich KJ, Billingsley GH, Huntoon PW (1997) Breccia-pipe and geologic map of the northeastern part of the Hualapai Indian Reservation and vicinity, Arizona. US Geol Surv Miscell Invest Ser Map I-2440, 2 sheets, scale 1:48,000, with report

Yaoru L, Feng’e Z, Jixiang Q, Jiaming X (2002) Xiuhong G (2002) Evaporite karst and resultant geohazards in China. Carbonates Evaporites 17:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03176482

Zukosky K (1995) An assessment of the potential to use water chemistry parameters to define ground water flow pathways at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. UNLV Retrospective Theses and Dissertations, no. 493. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds/493. Accessed June 2020

Funding

The geochemical and hydrologic investigation presented in this report was supported by the USGS Toxic Substances Hydrology Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 302 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beisner, K.R., Solder, J.E., Tillman, F.D. et al. Geochemical characterization of groundwater evolution south of Grand Canyon, Arizona (USA). Hydrogeol J 28, 1615–1633 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02192-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-020-02192-0