Abstract

Purpose

Early referral of patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to outpatient palliative care has been shown to increase survival and reduce unnecessary healthcare resource utilization. We aimed to determine outpatient palliative care referral rate and subsequent resource utilization in patients with stage IV NSCLC in a multistate, community-based hospital network and identify rates and reasons for admissions within a local healthcare system of Washington State.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of a multistate hospital network and a local healthcare system. Patients were identified using ICD billing codes. In the multistate network, 2844 patients diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC between January 1, 2013, and March 1, 2018, were reviewed. In the state healthcare system, 283 patients between August 2014 and June 2017 were reviewed.

Results

Referral for outpatient palliative care was low: 8% (217/2844) in the multistate network and 11% (32/283) in the local healthcare system. Early outpatient palliative care (6%, 10/156) was associated with a lower proportion of patients admitted into the intensive care unit in the last 30 days of life compared to no outpatient palliative care (15%, 399/2627; p = 0.003). Outpatient palliative care referral was associated with improved overall survival in Kaplan Meier survival analysis. Within the local system, 51% (104/204) of admissions could have been managed in outpatient setting, and of the patients admitted in the last 30 days of life, 59% (87/147) experienced in-hospital deaths.

Conclusion

We identified underutilization of outpatient palliative care services within stage IV NSCLC patients. Many patients with NSCLC experience hospitalization the last month of life and in-hospital death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Palliative care resources are available with the primary goal of easing symptoms associated with advanced disease and facilitating end-of-life care. Lung cancer incidence has steadily decreased; however, it remains the leading cause of cancer-related death (estimated 142,670 deaths in 2019) [1]. In a landmark randomized controlled trial of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, early referral to outpatient palliative care, defined as within 11 weeks of diagnosis, was associated with increased survival and improved quality of life, as well as a reduction in the unnecessary use of healthcare resources and increased documentation of resuscitation preferences [2]. Following this study, the World Health Organization created the first global resolution on palliative care in 2014, calling for members to implement and strengthen palliative care policies [3]. In addition, the American Society of Clinical Oncology updated clinical practice guidelines to recommend early integration of palliative care into standard oncology care of patients with advanced cancer and the National Quality Forum endorsed metrics to measure quality and aggressiveness of end-of-life care [4, 5].

Prior research has lacked a real world setting to observe outpatient palliative care within a concentrated population, but controlled trials have continued to identify improved overall survival and reduced resource utilization [6, 7]. In addition, studies have attempted to repeat these findings evaluating all cancers in medical systems such as the Veteran Health Administration and within palliative care units in hospitals [8,9,10,11].

Our aim was to determine the utilization of outpatient palliative care and the subsequent end-of-life resource utilization in patients with stage IV NSCLC in our multistate hospital network. We additionally evaluated our local healthcare system to identify admissions into the emergency department (ED), hospital, telemetry unit, intermediate care unit, and intensive care unit (ICU) in the last 30 days of life.

Methods

This study is a retrospective cohort review utilizing data from electronic medical records from centers associated with the Providence Health and Services network. Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish institutional review board. A query of electronic medical records was made, and patients were included if diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC within Providence Health and Services network between January 1, 2013 and March 31, 2018. Providence Health and Services network spans five states (Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, and Washington State) encompassing 37 centers, of which 76% (28/37) had dedicated outpatient palliative care services. Patient electronic medical records were queried for, clinical stage, hospital length of stay, ED/ICU admissions, and end-of-life preferences. Outpatient palliative care referrals were also identified, including timing related to diagnosis.

We performed a sub-analysis of patients within our local healthcare system, Swedish Healthcare Network, which resides within the Providence Health and Services network (Supplementary Figure). Swedish Healthcare comprises seven sites all of which possess outpatient palliative care services. Electronic medical records were queried for admissions in the last 30 days of life. Admitting symptoms, imaging studies, treatments, procedures/surgeries, length of stay, in-hospital deaths, and end-of-life wishes were recorded for each visit. Treatments were classified by whether they had the potential for outpatient management, and procedures/surgeries by whether they were considered palliative care.

Definitions

Early outpatient palliative care referral was defined as occurring within 11 weeks of NSCLC diagnosis, whereas late was > 11 weeks [2]. No outpatient palliative care was defined as having either no palliative care referral or a referral for inpatient palliative care [12]. In our community palliative care outpatient setting, the patients are seen by a palliative care physician specialist.

We utilized three of six endorsed National Quality Forum measures for the “Care of Patient at the End-of-Life” for which we had data available: proportion of patients who died from cancer admitted to the ICU, proportion of patients not admitted to hospice, and proportion admitted to hospice for less than three days [5].

Admissions were categorized as ED, hospital, telemetry unit, intermediate care unit, or ICU. A single overall admission was defined as a summation of consecutive admissions into different departments. Admissions in the last 30 days of life include only those admitted within 30 days or less before death, excluding admissions outside of the last 30 days which roll into the last 30 days. Direct admissions are defined as patients admitted directly from a treatment center, clinic, or for surgery. Lung cancer–related admissions are defined as an admission where symptoms could be attributed directly to lung cancer.

Management with palliative care only is defined as admissions where treatment for NSCLC symptoms could be accomplished with only palliative care. Admissions with potential outpatient management were defined by the patient receiving only interventions which could be administered in an outpatient setting. This excludes any intervention that requires inpatient admission. For example, a patient requiring mild fluid resuscitation and pain management could be managed purely in an outpatient setting and does not necessarily need an inpatient admission.

Statistical analysis

Multistate hospital network

Statistical analysis was performed by the Center for Cardiovascular Analytics, Research and Data Science. Pairwise p values were generated based on the following tests: Chi-square test or Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables including states, end-of-life directives, ED visits, ICU admissions and mortality within 30 days; and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for continuous variables such as age, time from diagnosis to referral, referral to death, length of stay, and continuous covariates. Median survival times were estimated and tested using log-rank test based on survival functions. P value comparisons were based on a significance level of 5%. Bonferroni adjustments were made for multiple comparisons resulting in some non-significant p values less than 0.05. Overall survival was compared using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank test.

Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards modeling was performed to examine for independent effects on the risk of death. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.6.0 (R Core Team 2019) and SPSS 24.0 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Local healthcare system

Continuous variables were summarized using median and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were summarized using counts and percentages. Univariate comparisons were performed using the Chi-squared test for categorical, and Welch’s t test or non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous covariates, followed by multivariable logistic regression to determine independent factors for whether patients were admitted in the last 30 days of their life or not.

Results

Multistate Hospital Network

We identified 3399 patients diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC between January 1, 2013 and March 1, 2018, via an electronic medical record query in our multistate, community-based hospital network. There were 555 exclusions: 494 for unknown death dates and 61 for having inaccessible data within their electronic medical record. Thus, 2844 patients were included in the analysis. Of the 2844 patients, 8% (217/2844) received outpatient palliative care referral, with 72% (156/217) occurring early, although this varied by state (Table 1).

Overall, 43% (1245/2844) of patients had ≥ 1 ED admission. However, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with no outpatient palliative care referral (1144/2627, 44%), early OPC referral (68/156, 44%) or late outpatient palliative care referral (33/61, 54%) (Table 1).

Early outpatient palliative care referrals (10/156, 6%) were associated with less patients admitted to the ICU in the last 30 days of life than patients with a late OPC referral (12/61, 20%; p = 0.004), as well as no outpatient palliative care referral (399/2627, 15%; p = 0.003). The median number of ICU admissions per patient was 1 (IQR: 1, 1). There was no difference in the ICU length of stay between the groups (Table 1).

Outpatient palliative care timing had no effect on end-of-life documentation (Table 1). There was no difference in the median days from outpatient palliative care referral to death in early outpatient palliative care (158; IQR: 55, 336) versus late outpatient palliative care referral (150; IQR: 58, 307; p = 0.596). There was a significant difference in the median days from diagnosis to death in early outpatient palliative care (181; IQR: 149, 216) compared to late outpatient palliative care referral (534; IQR: 426, 608; p < 0.001), as well as to no outpatient palliative care (108; IQR: 100, 116; p = 0.002). Kaplan–Meier method analysis estimated patients with both early and late outpatient palliative care as having greater overall survival compared to those with no outpatient palliative care (Fig. 1a). Kaplan Meier analysis demonstrated no difference between early and late outpatient palliative care (Fig. 1b).

No OPC referral was associated with a 3.9 adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for 30-day mortality when compared to early outpatient palliative care (Table 2). The hazard ratio (HR) adjusted by age and state was 1.5 (95% CI: 1.3, 1.8) times higher in patients with no outpatient palliative care compared to all those with outpatient palliative care, and 1.1 (95% CI: 0.8, 1.5) in early outpatient palliative care versus late outpatient palliative care.

Local healthcare system

We identified 375 patients between August 2014 and June 2017, of which 92 were excluded for unknown death dates. Thus, 283 patients were included in the analysis. Within the local healthcare system, 11% (32/283) received outpatient palliative care. There was no difference in the proportion of patients admitted within the last 30 days of life who received outpatient palliative care (14/32, 44%) compared to those who did not receive OPC (133/251, 53%; p = 0.320).

Outpatient palliative care did not impact two of the three National Quality Forum measurements. The proportion of patients who died from cancer and were not admitted into hospice was 41% (13/32) for outpatient palliative care referrals versus 44% (111/251; p = 0.850) for no outpatient palliative care referrals. Of those admitted to hospice, 16% (3/19) of those who received an outpatient palliative care referral spent less than 3 days in hospice compared to 9% (13/140; p = 0.411) of those without an outpatient palliative care referral. Outpatient palliative care referral was associated with less patients being admitted into the ICU from 17% (43/251) to 3% (1/32; p = 0.038).

Overall, 52% (147/283) of patients were admitted in the last 30 days of life to either the ED, hospital, telemetry unit, intermediate care unit or the ICU. Of those patients, 38% (108/283) had only one admission, 9% (25/283) had two, and 5% (14/283) had three or more admissions. The majority (187) of admissions were to the ED (Table 3). Of the ED admissions, 44% (83/187) occurred Monday to Friday 8am to 5 pm, 27% (51/187) were Monday to Friday after hours, and 28% (52/187) were on the weekend.

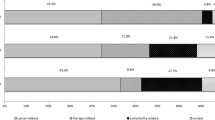

Admitting symptoms, management and median length of stay for each type of admission is shown in Table 3, and most admissions to each were lung cancer–related. There were 204 overall admissions, with 51% (104/204) having potential for outpatient management and 35% (72/204) having potential for palliative care management only (Fig. 2).

Admissions that could be potentially treated with outpatient management and palliative management. Overall admissions represent consecutive admissions from different departments, for example: patient enters ED then is transferred to HA and then to ICU, this is counted as 1 admission (Table 3)

In the last 30 days of life, patients spent a median of 7 (IQR: 4, 14) days in a hospital. Of the 147 patients admitted in the last 30 days of life, 41% (60/147) did not die in the hospital, 67% (40/60) were discharged to outpatient hospice. The remaining 87 patients (59%) admitted within the last 30 days of life died while in the hospital: 3% (3/87) in ED, 56% (49/87) in hospital, 5% (4/87) in telemetry, 11% (10/87) in intermediate care unit, and 24% (21/87) in ICU (Table 3). At the time of death, 63% (92/147) of patients admitted in their last 30 days had a do-not-resuscitate code status.

The odds of admission in the last 30 days of life decreased 16% with a twofold increase in distance lived from hospital (aOR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.73–0.95) (Table 4). Patients with a code status of do-not-resuscitate were less likely to be admitted (aOR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.22–0.91).

Discussion

We identified low utilization of outpatient palliative care in both our multistate hospital network and our local healthcare system. A strength of our study was the unique ability to look at regional palliative care utilization as well as a granular, local review that was able to assess hospital-based resource utilization of palliative care in NSCLC. Our data suggests that outpatient palliative care referrals remain low within the community setting at 8% in our multistate network and 11% in our local healthcare system.

In the small proportion of patients receiving outpatient palliative care referral, we found no difference in time from referral to death; however, we did find a significantly longer survival time associated with late outpatient palliative care referral from diagnosis to death. This finding differs from other reports where the timing of referral has shown to be consequential on symptom intensity and patient survival [2, 10, 11, 13]. It is unclear if this finding is related to the retrospective nature of the study, small numbers, or the community setting compared to prior studies often performed in academic centers. Another explanation could be that palliative care referrals are generated based on performance status, as opposed to objective guidelines [14]. Leaving palliative care referrals up to subjectivity allows for biases and perceptions about palliative care to influence referral patterns and frequency [15, 16]. Current literature suggests a discrepancy around acceptance of outpatient palliative care between providers and patients. Oncologists stated a lack of symptoms reported by patients and concerns that patients may oppose the referral as reasons for not referring to outpatient palliative care early, yet when surveyed, 98% of patients stated they would accept a referral if recommended [17]. It remains unclear how this information may be interpreted by academic versus community oncologists.

An interpretation of our data is that provider reluctance may result in these low referral rates. Further study of automated mechanisms based on national guideline recommendations may improve appropriate outpatient palliative care [18]. Automated suggestions for referrals like a best practice alerts are a potential option, as well as including non-physician providers in the process. Empowering oncology clinic nurses to make referrals may be a valid option. A study of nurses reported they felt involved in the transition to palliative care yet lacked the opportunities to contribute to decision making and referrals [19]. In addition, there has been a proposal to change the name of the service from “palliative care” to “supportive care” to address the perceived barrier that the terminology “palliative care” imparts. While studies report a more positive perception of “supportive care” terminology by medical oncologists and midlevel providers, as well as more inpatient referrals and earlier outpatient referrals; this concept is still controversial and debated among the palliative care community [20,21,22].

In our local network, outpatient palliative care consultation was not associated with lower admissions of stage IV NSCLC patients. However, chart review suggests that more than a third (35%) of these admissions could potentially be managed in the outpatient setting. We found ED visits were responsible for the greatest number of admissions in the last 30 days of life. Admitted patients spent a median of 7 days in the hospital with the majority suffering subsequent in-hospital death. Previous data of cancer patients suggest an increased likelihood of in-hospital death following unplanned hospital admissions, contrary to patient wishes to spend their final days at home [23]. Outpatient palliative care referral was associated with a reduction in the number of patients being admitted into the ICU in their last 30 days, similar to other studies reporting a lower rate of ICU admissions when referring early palliative care to advanced cancer patients [24].

We identified an association with early outpatient palliative care and decreased ICU admission, but no association to ED visits within the last 30 days. Prior research in small patient populations have shown trends of advanced cancer patients presenting with avoidable ED visits [25,26,27]. The discordance between these resources remains unclear. Closer review of ED visits noted nearly half (44%), occurred Monday-Friday, between 8am and 5 pm, times when outpatient oncologic resources such as infusion centers are available. Nearly a third of patients (28%) were seen on a weekend suggesting an expansion of outpatient oncologic facilities. In our local healthcare system, more than half of our overall admissions could have been managed with resources available in the outpatient setting. Thirty-five percent required management of symptoms related to NSCLC and are commonly managed with palliative measures alone. Creation of more robust supportive plans with the patient/family and direct pathways to outpatient designated resources for patients with advanced NSCLC may decrease expensive and stressful inpatient experiences and maximize in-home days as opposed to in-patient days. Cancer patients consume a significant amount of health care resources in the last 12 months of life and admissions to the hospital are costly [28, 29]. The emergence and persistence of the COVID-19 epidemic has shined a light on stressed inpatient resources and our need for greater ease of access and integrated clinic referral with outpatient resources for our vulnerable patients with advanced NSCLC.

Due to the retrospective nature of our study design, it remains difficult to elucidate the reason(s) why palliative care does not appear to have the anticipated impact based on prior studies; however, we also theorize that the impact of outpatient palliative care on resource utilization may depend on how the program is embedded in the care of the cancer patients. Differing models may include stand-alone consultations for symptom management versus true integration into treatment teams. We suspect that the act of referral may be insufficient to reduce resource utilization and suggest that measuring outpatient palliative care referral alone may not be the most important quality improvement metric. We are unaware of any current studies evaluating these questions but hypothesize that they may lead to different outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is a two-pronged retrospective review examining the use of outpatient palliative care in a real-world setting: this approach allowed us to create a snapshot of a large sample size while providing a more in-depth analysis on a subset. Our study is one of the first to analyze the use of outpatient palliative care within a defined cancer population in a non-academic setting. A limitation of our study is its retrospective design and inherent shortcomings and biases of such design. We assumed all patients within the system were billed thoroughly and had accurate charts. We did not investigate if palliative care consultations were carried out after referral. Billing codes constrained our ability to examine other measurements endorsed by the National Quality Forum. We had access to medical records associated with Providence Health and Services, potentially missing non-network providers of outpatient palliative care. However, many national database queries and compliance are often evaluated in this fashion.

Conclusion

The utilization of outpatient palliative care in stage IV NSCLC remains low, both within a large multistate network and one of its local healthcare networks. No survival benefit was associated with early versus late outpatient palliative care referral; however, both were associated with a survival benefit over no palliative care. The purported benefit in reduction of resource utilization was found to be weak at best; and most patients within our local healthcare system had in hospital days and death. The largest percentage of hospital resources were used during “normal business hours”, and most admissions were for NSCLC symptoms. Further research needs to examine alternative methods of referral to increase palliative care utilization and greater palliative care integration into care plans to decrease resource utilization considering that many of the admissions have the potential to be managed in the outpatient setting.

Data availability

Data and material can be made available upon request.

Code availability

Code can be made available upon request.

Approval was granted by the Swedish Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB). This is an observational study. The Swedish Medical Center IRB waived the need for ethical approval. This study was conducted retrospectively thus the need to provide individual consent was waived by the Swedish Medical Center IRB.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- RMST:

-

Restricted mean survival time

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 70:7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21590

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1000678

World Health Assembly (2014) Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov 2022

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ (2017) Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care:ASCO clinical practice guideline update summary. J Oncol Pract 13:119–121. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2016.017897

National Quality Forum (2016) Palliative and end-of-life care 2015–2016. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2016/12/Palliative_and_End-of-Life_Care_2015-2016.aspx. Accessed 7 Nov 2022

Eychmüller S, Zwahlen S, Fliedner MC et al (2021) Single early palliative care intervention added to usual oncology care for patients with advanced cancer: a randomized controlled trial (SENS Trial). Palliat Med 35:1108–1117. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211005340

Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A et al (2017) Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 35:834–841. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046

Gidwani R, Joyce N, Kinosian B et al (2016) Gap between recommendations and practice of palliative care and hospice in cancer patients. J Palliat Med 19:957–963. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0514

Masel EK, Schur S, Nemecek R et al (2017) Palliative care units in lung cancer in the real-world setting: a single institution’s experience and its implications. Ann Palliat Med 6:6–13. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2016.08.06

Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G et al (2017) Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:97. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2

Scibetta C, Kerr K, Mcguire J, Rabow MW (2016) The costs of waiting: implications of the timing of palliative care consultation among a cohort of decedents at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 19:69–75. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0119

Hochman MJ, Wolf S, Zafar SY et al (2016) Comparing unmet needs to optimize quality: characterizing inpatient and outpatient palliative care populations. J Pain Symptom Manage 51:1033–1039.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.338

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z et al (2015) Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438–1445. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362

Mo L, Urbauer DL, Bruera E, Hui D (2021) Recommendations for palliative and hospice care in NCCN guidelines for treatment of cancer. Oncologist 26:77–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ONCO.13515

Hui D, Kilgore K, Park M et al (2018) Pattern and predictors of outpatient palliative care referral among thoracic medical oncologists. Oncologist 23:1230–1235. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0094

Collins A, McLachlan SA, Philip J (2017) Initial perceptions of palliative care: an exploratory qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Palliat Med 31:825–832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317696420

Feld E, Singhi EK, Phillips S et al (2019) Palliative care referrals for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): patient and provider attitudes and practices. Clin Lung Cancer 20:e291–e298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.002

Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, Bruera E (2018) Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology:team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin 68:356–376. https://doi.org/10.3322/CAAC.21490

Kirby E, Broom A, Good P (2014) The role and significance of nurses in managing transitions to palliative care: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 4:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006026

Rhondali W, Burt S, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Bruera E, Dalal S (2013) Medical oncologists’ perception of palliative care programs and the impact of name change to supportive care on communication with patients during the referral process. A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care 11(5):397–404

Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D et al (2011) Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 16(1):105–111

Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL et al (2009) Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name? Cancer 115(9):2013–2021

Gamblin V, Prod’homme C, Lecoeuvre A et al (2021) Home hospitalization for palliative cancer care: factors associated with unplanned hospital admissions and death in hospital. BMC Palliat Care 20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00720-7

Romano AM, Gade KE, Nielsen G et al (2017) Early palliative care reduces end-of-life Intensive Care Unit (ICU) use but not ICU course in patients with advanced cancer. Oncologist 22:318–323. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0227

Cheung MC, Earle CC, Rangrej J et al (2015) Impact of aggressive management and palliative care on cancer costs in the final month of life. Cancer 121:3307–3315. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29485

Wallace EM, Cooney MC, Walsh J et al (2013) Why do palliative care patients present to the emergency department? Avoidable or unavoidable? Am J Hosp Palliat Med 30:253–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112447285

Delgado-Guay MO, Kim YJ, Shin SH et al (2015) Avoidable and unavoidable visits to the emergency department among patients with advanced cancer receiving outpatient palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 49:497–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.007

Rubin R (2021) The costs of US Emergency Department visits. JAMA 325:333. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.26936

Society of Critical Care Medicine (2012) Critical care statistics. Society of Critical Care Medicine 38:1–4. https://www.sccm.org/Communications/Critical-Care-Statistics

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Austin Meggyesy, Kerrie Buehler, and Joshua Rayburn were all responsible for data collection. Shu-Ching Chang and Shih-Ting Chiu were responsible for statistical analysis and presentation. Candice Wilshire, Christopher Gilbert, and Jed Gorden were responsible for designing and monitoring the study. Austin Meggyesy prepared the manuscript and all authors contributed to editing previous versions. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Swedish Medical Center IRB waived the need to attain consent to publish.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Poster presentations at American Thoracic Society; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; May 20, 2020 (moved virtual due to SARS-CoV-2 pandemic) and International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer 19th World Conference on Lung Cancer; Toronto, Canada; September 24, 2018.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meggyesy, A.M., Buehler, K.E., Wilshire, C.L. et al. Utilization of palliative care resource remains low, consuming potentially avoidable hospital admissions in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: a community-based retrospective review. Support Care Cancer 30, 10117–10126 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07364-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07364-0