Abstract

Objective

High fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is a frequently reported problem among cancer patients. Previous research has shown that younger age is associated with higher levels of FCR. However, little attention has been given to date about how FCR manifests itself among adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients. This study explores the prevalence, correlates of high FCR, and its association with HRQoL in cancer patients in their late adolescence or young adulthood.

Methods

Seventy-three AYA cancer patients, aged 18–35 years at diagnosis, consulted the AYA team of the Radboud University Medical Center completed questionnaires including the Cancer Worry Scale (CWS), Quality of Life-Cancer Survivors (QOL-CS), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Sociodemographic and medical data was collected by self-reported questionnaire.

Results

Forty-five participants experienced high FCR (62%), which was higher than the 31–52% reported in previous studies among mixed adult cancer patient samples. Sociodemographic and medical variables were not associated with levels of FCR. High FCR was significantly associated with lower levels of social and psychological functioning and overall HRQoL and higher levels of anxiety and psychological distress.

Conclusion

Results illustrate that FCR is a significant problem among AYA cancer patients consulting an AYA team, with participants reporting higher levels of FCR than cancer patients of mixed ages. Health care providers should pay specific attention to this problem by screening and the provision of appropriate psychosocial care when needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently national adolescent and young adult (AYA) programs have been formed in an attempt to bridge the gap between the pediatric and adult oncology services and to address the unmet supportive care needs of the AYA cancer patient group. Definitions of the AYA have evolved over time and there are currently differing perspectives regarding the appropriate definition of the AYA age range between countries. In the UK, AYAs are considered to be patients aged between 13 and 24 years. In the USA, the spectrum of AYA includes patients aged 15–39 years of age; whilst in the Netherlands, where the present study was conducted, AYAs are typically defined as patients aged 18–35 years at cancer diagnosis [1, 2]. Regardless of the specific definition of AYA, a cancer diagnosis may have profound effects on the lives of AYA cancer patients, interfering with the attainment of normal developmental milestones [3]. At a time when most AYAs are trying to make future plans for career, relationships, and children, the future can seem uncertain. Furthermore, cancer-related issues such as premature confrontation with mortality, changes in physical appearance, increased dependence on parents, disruptions of social life and school/employment because of treatment, and potential loss of reproductive capacity may become particularly distressing and could negatively impact their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [3,4,5,6]. Because the vast majority of AYA cancer patients will go on to be long-term survivors (relative 5-year survival of 82% [7]), it is important to optimize the quality of their survival.

Due to cancer occurring at a critical phase in life, AYA cancer patients (AYAs) have unique physical, psychological, and social care needs [8, 9]. Nevertheless, research involving AYAs aged 15–39 years at diagnosis reports a high number of unmet needs among AYAs, with psychosocial help for fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) as a key unmet need [10]. FCR has recently been defined as the “fear, worry, or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress” [11]. It has also been described as a “sword of Damocles” that hangs over survivors for the rest of their lives [12]. Whilst a normal level of FCR is adaptive because it can keep a person alert and aware of symptoms [13], high levels of FCR can adversely affect a person’s HRQoL and social activities [14, 15]. Cancer survivors with high levels FCR may engage in excessive monitoring for signs of potential recurrence and/or try to cognitively or behaviorally avoid reminders of their cancer [13]. High FCR is associated with both more unscheduled doctor appointments and unwillingness to be discharged from follow-up care [16,17,18,19], leading to increased health care costs [18]. Furthermore, patients with elevated FCR commonly report difficulties planning for the future [15], which may adversely impact on the developmental milestones of young adulthood although this has not been systematically investigated. Comparing of the prevalence of FCR across studies is difficult due to a lack of a consensus definition of high FCR [11]. However, a systematic review of FCR literature [14] suggests that moderate to high levels of FCR affect on average 49% of cancer patients and severe FCR affects on average 7% [14] and high levels of FCR persist over time when untreated [20]. Recent Dutch studies using the Cancer Worry Scale (CWS) report prevalence rates for high FCR of 31% in women breast cancer (n = 194) [21], 36% among men with localized prostate cancer (n = 283) [22], 38% in colorectal cancer patients (n = 76) [23], and 52% in gastrointestinal stromal tumor patients (GIST; n = 54) [24]. Younger age is the most consistent predictor of increased FCR among cancer patients [14, 20]. However, the majority of studies are conducted among breast cancer patients or mixed-aged adult samples. There is inconclusive evidence of the association between FCR and time since diagnosis or objective indices of risk of recurrence with some studies finding an association and others not [14]. To date, little data is available on the prevalence of FCR in the AYA population or the factors associated with increased levels of FCR in this age group. A recent study reported a FCR prevalence rate of 85.2% among AYA cancer patients aged 15–39 years. However, this study is limited by the fact that it used a single non-validated question to assess FCR and that it recruited a self-selected group who were users of a cancer survivorship website [25]. Studies involving cancer patients of mixed age show that FCR is associated with poorer HRQoL [14]; and another recent study has shown that in AYA cancer patients, this relationship is moderated by perceived growth [26].

This cross-sectional study explores the prevalence, correlates, and association with HRQoL of FCR in a sample of consecutively seen AYA cancer patients. A strength of the present study over existing research is that FCR is measured with a valid and reliable FCR-specific questionnaire with a cutoff for high FCR which has been validated in the Dutch adult cancer patient population [21, 23, 24]. A secondary aim was to compare the reported prevalence of FCR in the present sample to that of other studies of Dutch cancer survivors using the same outcome measure. Due to the fact that previous literature reports a consistent relationship between younger age and FCR, and AYAs experience cancer at a vulnerable phase of life where future goals are defined and coping skills need to be developed, it was hypothesized that AYAs would report a higher prevalence of FCR than has been reported in cancer patients of mixed ages (31–52%); participants with high FCR would have significantly lower HRQoL than with those with low FCR and that clinical characteristics would not be significantly associated with having high FCR.

Methods

Participants

Using the Dutch definition of AYA, patients aged 18–35 years at cancer diagnosis, who had been seen by at least one of the members of the AYA team of the Radboud University Medical Center (Raboudumc) in The Netherlands, were invited to participate in this study. The AYA team is a dedicated multidisciplinary team for patients aged 18 to 35 years at diagnosis including a medical oncologist, clinical nurse specialist, medical psychologist, and a social worker. Patients consulting the AYA team receive regular medical care from their own treating specialist at Raboudumc (oncologist, surgeon, hematologist, dermatologist, urologist, gynecologist, etc.) and visit the AYA team for age-specific questions and care needs. In general, patients visiting the AYA team represent a group of patients with high disease severity, diagnosed with relatively advanced stage of disease and undergoing intensive treatments, and reporting more problems with coping. Patients with lower stage disease (e.g., cervical cancer, melanoma), treated solely by surgery, are not often seen by the AYA team.

In order to depict the real-life heterogeneous sample of AYA cancer patients visiting the AYA team, this study included AYA patients independent of their treatment status (during or after treatment), type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and hormonal therapy or combination), or the number of visits to the AYA team. Inclusion commenced January 2012 and ended March 2016.

Procedure

Potential study participants were recruited via letters describing the study and inviting patients to participate in the study. Patients willing to participate had to actively opt-in to the study by providing written informed consent by email to a member of the AYA team. Participants were then sent a single set of questionnaires by email that could be completed online. The study was deemed exempt from full review and approval by a research ethics committee (CMO Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen).

Instruments

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic data, including age, gender, partnership, having children, living situation, educational level, and employment status, were gathered by self-report. Medical data, including tumor type, disease stage, treatment type, treatment status (on/off treatment), and time since initial diagnosis were extracted from the patients’ medical records by one of the researchers (SK).

Fear of cancer recurrence/progression

The Cancer Worry Scale (CWS) is used in research to assess concerns about developing cancer again (e.g., how often do you worry about developing cancer (again)?) and the impact of these concerns on daily functioning (e.g., have these thoughts interfered with your ability to do daily activities?) [21]. The CWS is a reliable (Cronbach’s alpha in this study = .89) and valid measure of FCR which has been validated in several studies involving Dutch cancer patients [21, 23, 24, 27]. The eight items of the CWS are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from never (1) to almost always (4). Scores range from 8 to 32 [28]. A cut-off scores of 13 or more is validated for prostate cancer survivors (sensitivity 86%; specificity 84%) [22], and 14 or more for breast (sensitivity 77%; specificity 81%) [21] and colorectal cancer survivors (sensitivity 86%; specificity 87%) [29] indicating high levels of FCR. The present study used a cut-off score of 14 or more to indicate high FCR.

Health-related quality of life

The Quality of Life for Cancer Survivors (QoL-CS) questionnaire was used to measure HRQoL. It consists of 41 items on the physical, psychological, social functioning, and religious impact of cancer on the life of the patient. Respondents rate themselves along an interval rating scale ranging from 0 to 10 for each item. For subscale scoring purposes, all items were ordered, so that 0 indicated the lowest or worst possible HRQoL and 10 indicated the highest or best possible HRQoL outcome. An overall QoL score was computed by averaging all 41 items [30]. Strong evidence for the validity and reliability of the instrument has been reported [31, 32]. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.35 for religious functioning to 0.91 for the total QoL scale score in this sample.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS is a self-report questionnaire comprising 14 items on a four-point Likert scale. Total score and subscales scores can be calculated for depression and anxiety (7 items each). Higher scores indicate more anxiety, depression, and psychological distress. Due to a lack of somatic items, the HADS is not confounded by the presence of physical symptoms and therefore suited for people with cancer [33]. The HADS is reliable [34] (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.77 in this sample) and validated for use in different groups of Dutch subjects and in cancer patients [35, 36].

Statistical analyses

The present study is a secondary analysis of a data collected to assess HRQoL among AYA cancer patients. Analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22 (SPSS), and two-sided p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, HRQoL, and psychological distress between patients with low and high levels of FCR were compared using chi-square and t tests (or Mann-Whitney U test), where appropriate. Given that a minimal clinically important difference for the primary outcome measure (CWS) has not been established, clinically meaningful differences were determined with Norman’s “rule of thumb,” using ~0.5 SD difference to indicate a threshold discriminant difference in scores [37]. To contextualize the findings of the present study, t tests were used to compare mean levels of FCR reported in the present sample with the results of other Dutch cancer survivors studies using the CWS, and chi-square was used to compare the proportions reporting high FCR with other studies.

Results

Sample characteristics

In total, 309 letters requesting participation in the study were sent to AYA cancer patients visiting one of the members of the AYA team. Eighty-nine participants, comprising 57% of those who opted-in to the study (n = 155) and 29% of those sent mailed invitations (n = 309), completed the online questionnaire. Four participants were excluded since they were diagnosed with cancer under the age of 18 years. Twelve patients were excluded from analyses because they had a recent recurrence (n = 5) or received palliative treatment (n = 7), making the item wording of the CWS irrelevant to them, resulting in final sample of 73 participants. Table 1 displays sociodemographic and clinical and treatment-related characteristics of the sample. Mean age at cancer diagnosis was 27.4 years (SD = 4.9) and average time since cancer diagnosis was 1.9 years (SD = 2.6). The most common diagnosis was testicular cancer (34%), followed by breast cancer (15%) and sarcoma (12%). The majority of participants had undergone surgery (84%) and chemotherapy (86%), and had completed treatment at time of study (76%).

Prevalence FCR

Mean score on the CWS for the AYA cancer sample was 14.9 (SD = 4.6). Forty-five AYA cancer patients (62%) scored 14 or higher on the CWS suggesting a high level of FCR. The percentage of AYA cancer patients scoring high on FCR was significantly higher than the 31% in breast cancer patients (t = 2.8, p = 0.007), 36% in prostate cancer patients (t = 5.4, p = < 0.001), 38% in colorectal cancer patients (t = 4.5, p = 0.002), but it did not differ significantly from 52% prevalence reported by GIST cancer patients (t = 0.7, p = 0.47) (Table 2).

Correlates of high FCR

There were no differences in sociodemographic (age, gender, partner, education, living situation, and occupational status) and clinical variables (type of tumor, type and phase of treatment, disease stage) between AYA cancer patients with high or low levels of FCR (Table 1). However, immunotherapy was significantly associated with high FCR (chi2 = 6.7, p = 0.01).

Association between high FCR, HRQoL, and psychological distress

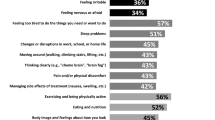

AYA cancer patients with high FCR (CWS ≥0 14) reported worse functioning in the psychological domain (t = 5.1; p < 0.01) and social functioning domain (t = 3.6; p < 0.01), and lower overall HRQoL (t = 4.5; p < 0.01), compared with those with low levels of FCR (Table 3). These differences were clinically relevant as well as statistically significant. No differences were found for physical and religious functioning. AYA patients with high levels of FCR reported significantly higher scores on anxiety (t = − 3.5; p < 0.01), and total distress (t = − 3.0; p < 0.01), compared with those with lower levels of FCR. These differences were of clinical relevance. No significant difference was found for depression.

Discussion

The present study is among the first to quantify the prevalence of high FCR in a sample of AYA cancer patients, aged 18–35 years at diagnosis who consulted at least one of the members of the multidisciplinary AYA team. High levels of FCR were reported among 62% of participants in the present sample. Whilst, there remains debate around definition of high FCR and a consensus definition of clinical FCR is currently under development [11], the results of the present study confirm our hypotheses that FCR, assessed with the CWS, is a common concern among AYA cancer patients and high FCR is more prevalent among AYAs than cancer patients of mixed ages and stages [21,22,23,24]. Consistent with past literature [14, 20] and as hypothesized, objective determinants of poor prognosis were not significantly associated with FCR in the present sample.

High prevalence rates of clinical FCR have been reported in other studies involving younger patients with a good prognosis. For example, Thewes et al. [38] found that 70% of survivors aged 18–45 years at diagnosis with early stage breast cancer reported clinical levels of FCR. Reasons for the higher prevalence in younger people with cancer are not well studied, but in breast cancer survivors, motherhood of young children, and the unexpected nature of life-threatening illness at an early age have been postulated [17, 39]. There is some evidence that the relationship between age and FCR may also be, in part, mediated by the perceived physical, social, or economic consequences of having a recurrence [39], anxiety [39, 40], coping style [41], and self-efficacy [42]. Due to small sample size, it was not possible to test mediators of FCR in the present sample, but future studies should explore this issue.

The prevalence of high FCR in the present AYA sample was significantly higher than has been previously reported among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients; however, it did not significantly differ from that reported among GIST patients [24]. Potential similarities between the GIST and AYA samples are that both groups included patients with poor prognosis, whereas the other samples included only patients treated with curative intent. Another potential explanation is that both AYA cancer and GIST are rare diseases, meaning that patients may have fewer social comparators and less information available to them; these factors might also contribute to increased uncertainty in GIST and AYA. Another possible explanation is that both groups included patients receiving novel targeted therapies. Targeted therapies are often associated with extended treatment duration and intensive monitoring for signs of treatment response or recurrence over longer periods of time than standard cancer treatments, due to the frequent checking for treatment response and/or recurrence over extended periods these treatments might contribute to higher levels of FCR [43]. Further research is required to better understand the relationship between novel cancer treatments and FCR.

Consistent with the results of several literature reviews exploring the factors associated with FCR, the present study found that higher FCR was associated with poorer psychological and social functioning and lower overall HRQoL [14, 20]. Physical symptoms can serve as triggers for FCR [24] and previous research has shown an association between FCR and the presence of physical symptoms among people with mixed cancer types [14, 20, 44]. However, it is noteworthy that in the present study, no association was found between FCR and physical HRQoL. This is in contrast to previous literature [14]. Interestingly, no difference was found between the proportions of patients reporting low versus high FCR for most conventional treatment modalities, with the exception of immunotherapy which was associated with higher FCR in the present sample.

In considering the results of the present study, several potential limitations should be acknowledged. To determine the prevalence of FCR in the present study, the higher (and more conservative) cut-off score for high FCR (13 vs. 14) was selected. A lower CWS cut-off score of 11 vs. 12 has been suggested for screening purposes [21], and a cut-off score of 12 vs. 13 has been used to detect high FCR in male prostate cancer patients [22]. Further research is needed to validate both the CWS and other common measures of FCR in AYA cancer patients. Given the high prevalence of FCR in AYAs, the results of this study underline the importance of establishing a psychometrically sound FCR screening questionnaire with a cut-off score specifically validated for the AYA population.

The cross-sectional design limits the determination of causal associations between the study variables. Furthermore, due to the small sample size, it was not possible to conduct multivariate analyses adjusting for confounding effects or to examine moderating or mediating factors. Although the role of clinical characteristics in FCR is inconsistent across studies, future studies involving larger samples are needed to determine whether the predictors identified in the present study are replicated when their effects are adjusted for the influence of age and clinical characteristics such as time since diagnosis, type of treatment, treatment status, and comorbidities. As this was a secondary analysis data on psychiatric morbidity and trait anxiety which were not available but future studies might consider including these as covariates to determine to what extent high comorbid with or influenced by psychiatric disorder or trait anxiety.

All participants received multidisciplinary care by a dedicated AYA team within an academic hospital setting. AYAs referred to this specialized team often present with more complex care needs and therefore it is unclear to what extent FCR levels reported in the present sample are representative of the level of FCR in the broader population. Patients in this sample were also diagnosed with relatively advanced stage of disease (18% in our sample compared to 4% stage 4 disease in total Dutch AYA population) and were treated with multiple treatment modalities. Lower stage cervical cancer, melanoma, and early stage testicular cancer are usually treated only with surgery. Therefore, the present sample might overestimate the disease severity of the entire AYA cancer population and may have contributed to the high-observed level of FCR in the present sample. Both factors may limit the generalizability of our results. Another limitation of our study is the low response rate, which is unfortunately not unusual in studies of young cancer patients [45], limiting the generalizability of our results. Longitudinal, population-based studies are needed to understand changes in FCR over the course of the cancer trajectory and to provide insights into the predictors of these changes. More research is also needed to identify the prevalence and predictors of higher FCR in a large representative sample of AYA cancer patients, including those in 15–18-year-old age range.

With regard to instrumentation of HRQoL, the current study relied upon a generic instrument with limited use in study samples consisting of young patients. There are currently no valid or reliable HRQoL instruments available for the entire AYA age range. The QoL-CS was selected because qualitative research highlights the need for tools measuring age-specific impact of cancer, such as employment challenges, social isolation, and sexual and relationship problems [46]. Internal consistency of the QoL-CS in the present sample was high for the total score (0.91) and good to acceptable for most subscales with the exception of religious functioning (0.35). Cultural differences in religiosity between the Netherlands and the USA (where the QoL-CS was originally developed) might account for this difference. More research is needed to validate existing HRQoL instruments specifically for the AYA population.

Although FCR is a growing area in the psycho-oncology literature, relatively few studies to date have focused specifically on AYA cancer patients. This study is one of the first to explore the issue of FCR in an AYA cancer population using an FCR-specific questionnaire with a validated cutoff. The present study found a significantly higher prevalence of FCR in this specific group of AYA cancer patients and a higher prevalence than has been reported in previous studies involving cancer patients of mixed ages. Based on the results of the present study, it is recommended that clinicians give greater attention to FCR in the clinical care of AYAs, where feasible-validated screening measures can be routinely used to identify problematic levels of FCR [21, 47]. Where routine screening of FCR is not feasible, clinicians should routinely ask about and normalize the presence of FCR and use questions to further explore whether FCR is chronic or bothersome and if there is a need for help to manage FCR. Patients who are severe or problematic may benefit from a growing number of evidence-based interventions for reducing high FCR [48,49,50,51,52]. A better understanding of FCR in AYA cancer patients will help clinicians identify patients who are in need of (psychosocial) intervention and when to most effectively intervene. Existing interventions are yet to be evaluated in an exclusively AYA population. However, as the theoretical foundations of existing interventions are relevant to all age groups, is it very likely that the therapeutic techniques they contain are equally relevant to AYA cancer survivors. However, some minor modification of patient resources (e.g., peer videos, patient examples in handouts) may make existing interventions more appealing and accessible to a younger audience. Given the potential impact of FCR on the developmental milestones of AYAs, further quantitative and qualitative research is needed to explore the functional impact of FCR on the lives of AYA cancer patients and to validate common measures of FCR in AYA populations. Future studies may therefore benefit from using multi-dimensional scales to assess FCR.

References

Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA (2016) Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr 170(5):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4689

Husson O, Manten-Horst E, van der Graaf WT (2016) Collaboration and networking. Progress Tumor Res 43:50–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447071

Zebrack BJ (2011) Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer 117(10 Suppl):2289–2294. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26056

D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B (2011) Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 117(10 Suppl):2329–2334. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26043

Zebrack B, Isaacson S (2012) Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 30(11):1221–1226. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467

Evan EE, Zeltzer LK (2006) Psychosocial dimensions of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Cancer 107(7 Suppl):1663–1671. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22107

Trama A, Botta L, Foschi R, Ferrari A, Stiller C, Desandes E, Maule MM, Merletti F, Gatta G, Group E-W (2016) Survival of European adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer in 2000-07: population-based data from EUROCARE-5. Lancet Oncol 17(7):896–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00162-5

Wong AW, Chang TT, Christopher K, Lau SC, Beaupin LK, Love B, Lipsey KL, Feuerstein M (2017) Patterns of unmet needs in adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors: in their own words. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract 11(6):751–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0613-4

Bibby H, White V, Thompson K, Anazodo A (2017) What are the unmet needs and care experiences of adolescents and young adults with cancer? A systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 6(1):6–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2016.0012

Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, Kent EE, XC W, West MM, Hamilton AS, Zebrack B, Bellizzi KM, Smith AW, Group AHSC (2012) Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv 6(3):239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9

Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Mutsaers B, Thewes B, Prins J, Dinkel A, Butow P (2016) From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer 24(8):3265–3268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5

Muzzin L, Anderson N, Figueredo A, Gudelis S (1994) The experience of cancer. Soc Sci Med 38(9):1201–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90185-6

Lee-Jones C, Humphries G, Dixon R, Hatcher M (1997) Fear of cancer recurrence; a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain the excaerbation of fears. Psycho-Oncologia 6:95–105

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, Ozakinci G (2013) Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract 7(3):300–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z

Custers JA, Gielissen MF, de Wilt JH, Honkoop A, Smilde TJ, van Spronsen DJ, van der Veld W, van der Graaf WT, Prins JB (2016) Towards an evidence-based model of fear of cancer recurrence for breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv:Res Pract 11(1):41–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0558-z

Cannon AJ, Darrington DL, Reed EC, Loberiza FR Jr (2011) Spirituality, patients’ worry, and follow-up health-care utilization among cancer survivors. J Support Oncol 9(4):141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2011.03.001

Thewes B, Butow P, Bell ML, Beith J, Stuart-Harris R, Grossi M, Capp A, Dalley D (2012) Fear of cancer recurrence in young women with a history of early-stage breast cancer: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and association with health behaviours. Supp Care Cancer 20(11):2651–2659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1371-x

Lebel S, Tomei C, Feldstain A, Beattie S, McCallum M (2013) Does fear of cancer recurrence predict cancer survivors’ health care use? Support Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 21(3):901–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1685-3

Glynne-Jones R, Chait I, Thomas SF (1997) When and how to discharge cancer survivors in long term remission from follow-up: the effectiveness of a contract. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 9(1):25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0936-6555(97)80055-6

Crist JV, Grunfeld EA (2013) Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 22(5):978–986. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3114

Custers JA, van den Berg SW, van Laarhoven HW, Bleiker EM, Gielissen MF, Prins JB (2014) The cancer worry scale: detecting fear of recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 37(1):E44–E50. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182813a17

van de Wal M, van Oort I, Schouten J, Thewes B, Gielissen M, Prins J (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence in prostate cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 55(7):1–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2016.1150607

Custers JA, Gielissen MF, Janssen SH, de Wilt JH, Prins JB (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence in colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24(2):555–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2808-4

Custers JA, Tielen R, Prins JB, de Wilt JH, Gielissen MF, van der Graaf WT (2015) Fear of progression in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): is extended lifetime related to the sword of Damocles? Acta Oncol 54(8):1202–1208. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2014.1003960

Shay LA, Carpentier MY, Vernon SW (2016) Prevalence and correlates of fear of recurrence among adolescent and young adult versus older adult post-treatment cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 24(11):4689–4696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3317-9

Cho D, Park CL (2017) Moderating effects of perceived growth on the association between fear of cancer recurrence and health-related quality of life among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 35(2):148–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2016.1247408

van de Wal M, van Oort I, Schouten J, Thewes B, Gielissen M, Prins J (2016) Fear of cancer recurrence in prostate cancer survivors. Acta Oncol 55(7):821–827. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2016.1150607

Douma KF, Aaronson NK, Vasen HF, Gerritsma MA, Gundy CM, Janssen EP, Vriends AH, Cats A, Verhoef S, Bleiker EM (2010) Psychological distress and use of psychosocial support in familial adenomatous polyposis. Psychooncology 19(3):289–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1570

Custers JA, Gielissen MF, Janssen SH, de Wilt JH, Prins JB (2015) Fear of cancer recurrence in colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 24(2):555–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2808-4

Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M (1995) Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 4(6):523–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00634747

Garratt A, Schmidt L, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R (2002) Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ 324(7351):1417. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1417

Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P (1996) An evaluation of the quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 39(3):261–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01806154

Zigmond A, Snaith R (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, Kempen GI, Speckens AE, Van Hemert AM (1997) A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med 27(2):363–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004382

Vodermaier A, Millman RD (2011) Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 19(12):1899–1908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1251-4

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41(5):582–592. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C

Uecker J, Regnerus M, Vaaler M (2007) Losing my religion: the social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Soc Forces 85(4):1667–1692. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0083

Lebel S, Beattie S, Ares I, Bielajew C (2013) Young and worried: age and fear of recurrence among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol 32(6):695–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030186

Thewes B, Bell ML, Butow P, Beith J, Boyle F, Friedlander M, McLachlan SA, Members of the FCRSAC (2013) Psychological morbidity and stress but not social factors influence level of fear of cancer recurrence in young women with early breast cancer: results of a cross-sectional study. Psychooncology 22(12):2797–2806. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3348

Thewes B, Lebel S, Seguin Leclair C, Butow P (2016) A qualitative exploration of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) amongst Australian and Canadian breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 24(5):2269–2276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3025-x

Ziner KW, Sledge GW, Bell CJ, Johns S, Miller KD, Champion VL (2012) Predicting fear of breast cancer recurrence and self-efficacy in survivors by age at diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 39(3):287–295. https://doi.org/10.1188/12.ONF.287-295

Thewes B, Husson O, Poort H, Custers JAE, Butow PN, McLachlan SA, Prins JB (2017) Fear of cancer recurrence in an era of personalized medicine. J Clin Oncol 35(29):3275–3278. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8212

Mehnert A, Koch U, Sundermann C, Dinkel A (2013) Predictors of fear of recurrence in patients one year after cancer rehabilitation: a prospective study. Acta Oncol 52(6):1102–1109. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2013.765063

Rosenberg AR, Bona K, Wharton CM, Bradford M, Shaffer ML, Wolfe J, Baker KS (2016) Adolescent and young adult patient engagement and participation in survey-based research: a report from the “resilience in adolescents and young adults with cancer” study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63(4):734–736. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25843

Kuhlthau K, Luff D, Delahaye J, Wong A, Yock T, Huang M, Park ER (2015) Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult survivors of central nervous system tumors: identifying domains from a survivor perspective. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 32(6):385–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454214563752

Fardell JE, Jones G, Smith AB, Lebel S, Thewes B, Costa D, Tiller K, Simard S, Feldstain A, Beattie S, McCallum M, Butow P (2017) Exploring the screening capacity of the fear of cancer recurrence inventory-short form for clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4516

van de Wal M, Thewes B, Gielissen M, Speckens A, Prins J (2017) Efficacy of blended cognitive behavior therapy for high fear of recurrence in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: the SWORD study, a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 35(19):2173–2183. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2016.70.5301

Herschbach P, Book K, Dinkel A, Berg P, Waadt S, Duran G, Engst-Hastreiter U, Henrich G (2010) Evaluation of two group therapies to reduce fear of progression in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer 18(4):471–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0696-1

Butow PN, Bell ML, Smith AB, Fardell JE, Thewes B, Turner J, Gilchrist J, Beith J, Girgis A, Sharpe L, Shih S, Mihalopoulos C, members of the Conquer Fear Authorship G (2013) Conquer fear: protocol of a randomised controlled trial of a psychological intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence. BMC Cancer 13(1):201. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-201

Van de Wal M, Thewes B, Gielissen M, Speckens A, Prins J (under editorial review) efficacy of blended cognitive behavior therapy for high fear of recurrence in breast, prostate and colorectal cancer survivors; the SWORD-study, a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol

Smith A, Thewes B, Turner J, Gilchrist J, Fardell J, Sharpe L, Bell ML, Girgis A, Grier M, Byrne D, Clutton S, Butow P (2015) Pilot of a theoretically grounded psychologist-delivered intervention for fear of cancer recurrence (conquer fear). Psychooncology 24(8):967–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3775

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This manuscript is original research and it has not been submitted or published elsewhere. Each author has participated in the design, preparation, and critical review of the manuscript and takes public responsibility for the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was deemed exempt from full review and approval by a research ethics committee (CMO Regio Arnhem-Nijmegen).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Thewes, B., Kaal, S.E.J., Custers, J.A.E. et al. Prevalence and correlates of high fear of cancer recurrence in late adolescents and young adults consulting a specialist adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer service. Support Care Cancer 26, 1479–1487 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3975-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3975-2