Abstract

Free-living amoebae belonging to Acanthamoeba genus are widely distributed protozoans which are able to cause infection in humans and other animals such as keratitis and encephalitis. Acanthamoeba keratitis is a vision-threatening corneal infection with currently no available fully effective treatment. Moreover, the available therapeutic options are insufficient and are very toxic to the eye. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of more effective anti-amoebic agents. Nanotechnology approaches have been recently reported to be useful for the elucidation antimicrobial, antiviral, antifungal and antiprotozoal activities and thus, they could be a good approach for the development of anti-Acanthamoeba agents. Therefore, this study was aimed to explore the activity and cytotoxicity of tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles, pure silver nanoparticles and pure gold nanoparticles against clinical strains of Acanthamoeba spp. The obtained results showed a significant anti-amoebic effect of the tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles which also presented low cytotoxicity. Moreover, tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles were well absorbed by the trophozoites and did not induce encystation. On the other hand, pure silver nanoparticles were only slightly active against the trophozoite stage and pure gold nanoparticles did not show any activity. In conclusion and based on the observed results, silver nanoparticle conjugation with tannic acid may be considered as potential agent against Acanthamoeba spp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acanthamoeba genus is a widely distributed, free-living protozoa which includes some strains with the ability to cause infection in animals. Among them, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) a sight-threatening infection of the cornea has gained importance worldwide due to an increase in the reports of AK every year (Lorenzo-Morales et al. 2013; Chomicz et al. 2016; McKelvie et al. 2018; Walochnik et al. 2015). Lately, this genus has also been reported to act as vehicle of potentially pathogenic endosymbionts (Scheid 2007; Scheikl et al. 2016; Müller et al. 2016).

Regarding AK, the main key predisposing factors of this infection include contact lens use, corneal trauma and exposition of eye to contaminated water. Amoebae mainly localized in the corneal epithelium may also invade the underlying stroma and infiltrate through the corneal nerves, causing neuritis and necrosis. AK is still often misdiagnosed as fungal or viral keratitis, which results in delay of proper treatment and could eventually lead to loss of vision. So far, no drug has been described as a single fully effective treatment against AK and current therapeutic approaches are restricted to the application of chlorhexidine digluconate combined with propamidine isethionate or hexamidine. Unfortunately, prolonged treatment with these therapeutic agents is very toxic for the human eye. Summarizing, there is an urgent need for the development of novel treatments that would be less toxic to the eye and more effective against both trophozoite and cyst stages of Acanthamoeba spp. (Clarke et al. 2012; Lorenzo-Morales et al. 2015; Padzik et al. 2017).

Synthesized nanoparticles (NPs) are currently proposed as a new generation of antimicrobial, antiviral antiparasitic and antifungal agents (Shahverdi et al. 2007; Sondi and Salopek-Sondi 2004). Regarding the previously reported activity against parasitic organisms, silver nanoparticles have been widely tested including reports of their activity on hematophagous vectors such as Anopheles sp., Culex sp., Haemaphysalis sp. (Marimuthu et al. 2011; Jayaseelan et al. 2012) and helminths, Echinococcus granulosus, Schistosoma japonicum (Rahimi et al. 2015; Cheng et al. 2013). Moreover, the anti-protozoal activity of silver nanoparticles has been described against Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium parvum, Toxoplasma gondii, Leishmania spp. and Plasmodium spp. (Said et al. 2012; Panneerselvam et al. 2016; Saad et al. 2015; Ullah et al. 2018; Rai et al. 2017; Adeyemi et al. 2017). Gold nanoparticles have not been tested intensively, but their anti-helmintic and anti-protozoal activity was also investigated and confirmed (Bonelli 2018; Roy et al. 2017).

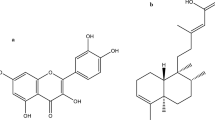

On the other hand, it is known that some plant metabolites such as flavonoids, alkaloids or terpenes present anti-parasitic activity (El-Sayed et al. 2012; Hajaji et al. 2017). Among them, tannins are polyphenolic plant metabolites with confirmed anti-obesity, anti-diabetes, anti-oxidant and anti-microbial activity. Furthermore, the extracts might be usable as a new dietary supplement, which could control the human intestinal microbiome (Ogawa and Yazaki 2018). Tannins are capable to form insoluble complexes with nucleic acids, carbohydrates, proteins and to chelate metal ions. Tannic acid (penta-m-digalloyl glucose) is the simplest, hydrolysable tannin with confirmed anti-microbial, anti-cancer and anti-oxidant activity (Haslam 2007; Scalbert 1989; Nelofer et al. 2000; Athar et al. 1989).

In this study, the activity and cytotoxicity of tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles (AgTANPs), pure silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and pure gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) was investigated against clinical strains of Acanthamoeba spp.

Material and methods

Isolation, cultivation and molecular identification of the strains

Three Acanthamoeba spp. clinical strains obtained from corneal scrapes of patients with AK, respectively, P1, P13 and P19, were initially examined in wet-mount slides using sterile saline solutions. In the clinical diagnosis, non-invasive methods of slit-lamp, also called biomicroscopy, and in vivo confocal microscopy were used. Both methods were performed to capture digital images of the cornea which allowed preliminary identification of the infectious agent. Isolates were cultured axenically in 25-cm2 culture tissue flasks (without shaking) at 27 °C in PYG medium [0.75% (w/v) proteose peptone, 0.75% (w/v) yeast extract and 1.5% (w/v) glucose] containing gentamicin 10 mg/mL in the Department of Medical Biology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland. Additionally, the ATCC 30010 type strain A. castellanii Neff was used as a control strain. All strains were subcultured twice a month and checked for their growth under direct light microscope using Bürker chamber (haemocytometer). Both clinical samples and cultured isolates were genotyped based on 18S rRNA sequence analysis as described previously (Chomicz et al. 2015).

Nanoparticles

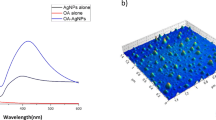

All nanoparticles (NPs) used in this study were kindly provided by the Department of Animal Nutrition and Food Science, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Poland. The pure silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and pure gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were obtained from Nano-Tech (Warsaw, Poland). Both hydrocolloids of AuNPs and AgNPs were produced by an electric non-explosive method from high purity metals and demineralized water (Polish patent 380649). The structures of the nanoparticles were visualized by a JEM-1220 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles (AgTANPs) were synthesized by chemical reduction method using silver nitrate (AgNO3) purity 99.999% (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). AgTANPs were prepared by mixing the heated aqueous solution of AgNO3 (95.2 g, 0.017%) with the aqueous solution of tannic acid (0.6 g, 5% C76H52O46 Sigma-Aldrich). The long-term stability of the colloidal dispersions of all tested NPs (zeta potential) was measured and confirmed by the electrophoretic light-scattering method with a Zetasizer Nano ZS, model ZEN3500 (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) (Orlowski et al. 2014; Urbańska et al. 2015; Zielinska et al. 2011).

Activity assays

AuNPs, AgNPs and AgTANPs at concentrations of 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 and 2.5 ppm were examined in vitro and compared for their anti-amoebic activity. To determine the efficacy of the tested NPs against the trophozoite stage (log growth phase after 6 days following subculturing), a previously described colorimetric 96-well microtitre plate assay, based on the oxido-reduction of AlamarBlue was used (McBride et al. 2005). Subsequently, the plates were analyzed over a period of 72 to 96 h on the Synergy HTX Multi mode reader (BioTek) with Gen5 program using a test wavelength of 570 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm. For those strains that were sensitive to the tested NPs, the 50% (IC50) and 90% (IC90) inhibitory concentrations were calculated and extrapolated by linear regression analysis. The inhibition curves of the analysis were developed. All experiments were performed three times, each in triplicate. Standard deviation and mean values were calculated. Amoebae in both control and tested assays were observed by Leica DMi8 inverted microscope using a Leica MC190 HD camera.

Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles

The cytotoxicity assays were performed using a fibroblast HS-5 cell line (ATCC). A commercial kit for the evaluation of drug-induced cytotoxic effects based on the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity released to the media (Pierce LDH cytotoxicity assay kit 88953, 88954) was used as per protocol. In order to set up the assay, HS-5 cells were plated in 96-well plates (13.5 × 103 cells per well) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Forty five minutes before collecting the supernatant, 10 μL of Lysis Buffer (10×) was added to another set of triplicated wells containing Target Cell Maximal LDH Release Control and Volume Correction Control. At the end of incubation, plates were centrifuged at 250×g for 3 min. Fifty microlitres of each sample medium to a 96-well flat bottom plate in triplicate wells was transferred and 50 μL of reaction mixture to each sample well was added and mixed by gentle tapping. All was incubated at room temperature for 30 min protected from light. At the end, 50 μL of stop solution was added to each sample well and mixed by gentle tapping. To calculate the % of cytotoxicity, absorbance was measured at 490 and 680 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy

The samples were cut into pieces of 1 mm3 and fixed in the 2.5% solution of glutaraldehyde (grade I, 25% in H2O, purified for electron microscopy use in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9)). Then, the samples were transferred into the 1% solution of osmium tetroxide (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.9) for 1 h and subsequently rinsed in distilled water, dehydrated in the ethanol gradient and impregnated with epoxy embedding resin (Epoxy–Embedding Kit, Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich). After 24 h, the samples were embedded in the same resin and baked for 24 h at 36 °C. Then, the blocks were transferred into 60 °C and baked for another 24 h. The blocks were cut into ultrathin sections (50–80 nm) using an ultramicrotome (LKB Ultratome III, Sweden) and transferred onto copper grids, 200 mesh (Agar Scientific Ltd. GB). Subsequently, the sections were contrasted using uranyl acetate (uranyl acetate dehydrate, ACS reagent, 98.0%, Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich) and lead citrate (citrate tribasic trihydrate for electron microscopy, Sigma-Aldrich). The morphological structure of each specimen was inspected using a JEM-1220 transmission electron microscope (TEM) at 80 keV (JOEL, Japan) coupled with a digital camera (Morada) and Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions software (Olympus, Germany).

Results

Characterisation of nanoparticles

The tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles (AgTANPs), pure silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and pure gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) solutions were characterized by TEM technique. The obtained results showed that tested nanoparticles ranged 10–100 nm in diameter (Fig. 1).

Genotyping

All tested Acanthamoeba clinical isolates were classified to the T4 group. The P1 strain was classified as Acanthamoeba polyphaga at the morphological level and P13 strain as A. castellanii, whereas P19 isolate was only classified at the genus level.

Nanoparticles activity and cytotoxicity

The obtained results of the in vitro NP tests against the Acanthamoeba spp. trophozoites varied and depended on the type of NPs used. AgTANPs, as the only ones, acted in the dose-dependent manner. All tested nanoparticles showed similar cytotoxicity on the fibroblasts at tested concentrations. The calculated 50% cytotoxicity was achieved at 30 ppm while 90% toxicity was achieved at 120 ppm.

The most favourable anti-amoebic effect in relation to cytotoxicity was revealed in assays with AgTANPs. The lowest calculated IC50 was 16 ppm for the P13 strain after 72 h of incubation (Fig. 2) and 14 ppm for the Neff strain after 96 h of incubation. The lowest calculated IC90 was 67 ppm for the P13 strain after 72 h of incubation (Fig. 3).

The AgNPs were much less effective against Acanthamoeba trophozoites. Particularly, the lowest calculated IC50 was 55 ppm for the Neff strain after 96 h of incubation. It is noteworthy that all clinical isolates were resistant to all tested doses of AgNPs.

The hydrocolloid AuNPs were not active against all selected Acanthamoeba strains at all tested doses.

Both AgTANPs and pure AgNPs were well absorbed by the trophozoites. The NPs were visible inside the trophozoites just after 2 h of incubation. Amoebae remained filled up with NPs for the whole tested period (Fig. 4).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (a, b, c) of the Acanthamoeba castellanii Neff strain trophozoite after 72 h of incubation with 25 ppm of AgTANPs. The arrows show absorbed nanoparticles inside the trophozoites. The intracellular organelles are marked as follows: (pm) plasmatic membrane, (m) mitochondria, (n) nucleus, (er) endoplasmic reticulum, (v) vacuole

Discussion

Currently, there is no definitive effective therapy against AK. In most cases, diamides and biguanides are the first line of treatment as their amoebicidal activity was confirmed by in vitro studies. Unfortunately, these therapies are very invasive. Prolonged therapy leads to higher toxic effects on the cornea and may also stimulate amoebae encystation (Lorenzo-Morales et al. 2015).

Different NPs, mainly AgNPs and AuNPs, have been tested in vitro for their activity on pathogenic microorganisms. Due to these promising results, some NPs have started to be considered as a new generation of anti-microbial, anti-fungal, anti-parasitic and anti-viral agents (Bondarenko et al. 2013). However, there are just a few available studies on the activity of NPs against amphizoic protozoans including Acanthamoeba. Regarding studies in Acanthamoeba, AgNPs were tested against the environmental Acanthamoeba strain ATCC 30234. In this case, the obtained results showed significant dose-dependent decrease of adherence ability and metabolic activity after 96 h of exposure (Grün et al. 2017). The silver containing solutions were also examined by Willcox et al. (2010). The results indicated that the viability of exposed Acanthamoeba polyphaga trophozoites, measured by the track forming units (TFU) calculation, was reduced. In our experiments, AgNPs were active only against the Neff (environmental) strain. Interestingly, all tested clinical strains were not sensitive to the pure AgNPs and AuNPs.

In our study, it was confirmed that both silver nanoparticles were absorbed by the trophozoites and internalized. The pathway of nanosilver action has been widely studied but their mechanism of action is still not fully elucidated yet. Previous studies in bacteria have reported that AgNPs destabilize the cell membrane, collapse the plasmatic membrane potential and deplete the levels of intracellular ATP (Lok et al. 2006). Most probably, AgNPs affect the cell membrane and react with proteins by releasing silver ions. In addition, it has been recently confirmed that AgNPs cause oxidative damage within the cell (Yan et al. 2018). The study on Candida albicans revealed that AgNPs induced oxidative stress-mediated programmed cell death through the accumulation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and affected other cellular targets such as: membranes, ergosterol content, cellular morphology and cell ultrastructural components (Radhakrishnan et al. 2018). Furthermore, it seems that AgNPs possess multitargeted mode of action that results in anti-microbial, anti-fungal and anti-protozoal activity. We showed that AgTANPs were significantly more effective against Acanthamoeba than pure AgNPs and AuNPs. This effect was sustained against all tested clinical strains. The best anti-amoebic effect was noted against Neff and P13 clinical strain for which IC50 was the most favourable in relation to cytotoxicity. As absorbtion of AgTANPs and AgNPs by trophozoites was similar, it suggests that tannic acid modification increased significantly biological effectiveness of this conjugation. Moreover, AgTANPs had no impact on the encystment rate, which remained at the same level when compared to the control assays. In studies performed by other authors, the amoebicidal activity against A. castellanii trophozoites was also confirmed for the AgNPs conjugated with a plant extracts (Borase et al. 2013). It seems that combination of AgNPs and plant metabolites might be a promising approach in the treatment of the Acanthamoeba infection.

The results of our studies suggest that AgTANPs may be considered as the potential agents against Acanthamoeba spp. Nevertheless, further studies should be conducted to elucidate their mechanisms of action.

References

Adeyemi OS, Murata Y, Sugi T, Kato K (2017) Inorganic nanoparticles kill Toxoplasma gondii via changes in redox status and mitochondrial membrane potential. Int J Nanomedicine 12:1647–1661. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S122178

Athar M, Khan WA, Mukhtar H (1989) Effect of dietary tannic acid on epidermal, lung, and forestomach polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism and tumorigenicity in Sencar mice. Cancer Res 49:5784–5788

Bondarenko O, Juganson K, Ivask A, Kasemets K, Mortimer M, Kahru A (2013) Toxicity of ag, CuO and ZnO nanoparticles to selected environmentally relevant test organisms and mammalian cells in vitro: a critical review. Arch Toxicol 87:1181–1200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-013-1079-4

Bonelli G (2018) Gold nanoparticles - against parasites and insect vectors. Acta Trop 178:73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.10.021

Borase HP, Patil CD, Sauter IP, Rott MB, Patil SV (2013) Amoebicidal activity of phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles and their in vitro cytotoxicity to human cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett 345:127–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6968.12195

Cheng Y, Chen X, Song W, Kong Z, Li P, Liu Y (2013) Contribution of silver ions to the inhibition of infectivity of Schistosoma japonicum cercariae caused by silver nanoparticles. Parasitology 140:617–625. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182012002211

Chomicz L, Conn DB, Padzik M, Szaflik JP, Walochnik J, Zawadzki PJ, Pawłowski W, Dybicz M (2015) Emerging threats for human health in Poland: pathogenic isolates from drug resistant Acanthamoeba keratitis monitored in terms of their in vitro dynamics and temperature adaptability. Biomed Res Int 2015:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/231285

Chomicz L, Szaflik JP, Padzik M, Izdebska J (2016) Acanthamoeba Keratitis: The Emerging Vision- 2 Threatening Corneal Disease. Advances in Common Eye Infections. Intech 99–120. https://doi.org/10.5772/64848

Clarke B, Sinha A, Parmar DN, Sykakis E (2012) Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J Ophthalmol 2012:484–892. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/484892

El-Sayed NM, Ismail KA, Ahmed SAEG, Hetta MH (2012) In vitro amoebicidal activity of ethanolic extracts of Arachishypogaea L., Curcuma longa L., Pancratium maritimum L. on Acanthamoeba castellanii cysts. Parasitol Res 110:1985–1992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-011-2727-3

Grün AL, Scheid P, Hauröder B, Emmerlingand C, Manz W (2017) Assessment of the effect of silver nanoparticles on the relevant soil protozoan genus Acanthamoeba. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 180:602–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201700277

Hajaji S, Sifaoui I, López-Arencibia A, Reyes-Batlle M, Valladares B, Pinero JE, Lorenzo-Morales J, Akkari H (2017) Amoebicidal activity of α-bisabolol, the main sesquiterpene in chamomile (MatricariarecutitaL.) essential oil against the trophozoite stage of Acanthamoeba castellani Neff. Acta Parasitol 62:290–295. https://doi.org/10.1515/ap-2017-0036

Haslam E (2007) Vegetable tannins - lessons of a plant phytochemical life time. Phytochemistry 68:2713–2721. https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.200817253

Jayaseelan C, Rahuman AA, Kirthi AV, Marimuthu S, Santhoshkumar T, Bagavan A, Gaurav K, Karthik L, Rao KB (2012) Novel microbial route to synthesize ZnO nanoparticles using Aeromonas hydrophila and their activity against pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 90:78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2012.01.006

Lok CN, Ho CM, Chen R, He QY, Yu WY, Sun H, Tam PK, Chiu JF, Che CM (2006) Proteomic analysis of the mode of antibacterial action of silver nanoparticles. Proteome Res 5:916–924. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr0504079

Lorenzo-Morales J, Martín-Navarro CM, López-Arencibia A, Arnalich-Montiel F, Piñero JE, Valladares B (2013) Acanthamoeba keratitis: an emerging disease gathering importance worldwide? Trends Parasitol 29:181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.006

Lorenzo-Morales J, Khan NA, Walochnik J (2015) An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite 22:10. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2015010

Marimuthu S, Rahuman AA, Rajakumar G, Kumar TS, Kirthi AV, Jayaseelan C, Bagavan A, Zahir AA, Elango G, Kamaraj C (2011) Evaluation of green synthesized green silver nanoparticles against parasites. Parasitol Res 108:1541–1549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-2212-4

McBride J, Ingram PR, Henriquez FL, Roberts CW (2005) Development of colorimetric microtiter plate assay for assessment of antimicrobials against Acanthamoeba. J Clin Microbiol 43:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.43.2.629-634.2005

McKelvie J, Alshiakhi M, Ziaei M, Patel DV, McGhee CN (2018) The rising tide of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Auckland, New Zealand: a 7-year review of presentation, diagnosis and outcomes (2009-2016). Clin Exp Ophthalmol 46:600–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.13166

Müller A, Walochnik J, Wagner M, Schmitz-Esser S (2016) A clinical Acanthamoeba isolate harboring two distinct bacterial endosymbionts. Eur J Protistol 56:21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejop.2016.04.002

Nelofer SK, Ahmad A, Hadi SM (2000) Anti-oxidant, pro-oxidant properties of tannic acid and its binding to DNA. Chem Biol Interact 125:177–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00143-5

Ogawa S, Yazaki Y (2018) Tannins from Acacia mearnsii De wild. Bark: tannin determination and biological activities. Molecules 23:837. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040837

Orlowski P, Tomaszewska E, Gniadek M, Baska P, Nowakowska J, Sokolowska J, Nowak Z, Donten M, Celichowski G, Grobelny J, Krzyzowska M (2014) Tannic acid modified silver nanoparticles show antiviral activity in herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. PLoS One 9:104–113. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104113

Padzik M, Hendiger EB, Szaflik JP, Chomicz L (2017) Pełzaki z rodzaju Acanthamoeba – czynniki etiologiczne stanów patologicznych ludzkiego organizmu (amoebae of the genus Acanthamoeba – pathological agents in humans). Post Mikrobiol 56:429–439

Panneerselvam C, Murugan K, Roni M, Aziz AT, Suresh U, Rajaganesh R, Madhiyazhagan P, Subramaniam J, Dinesh D, Nicoletti M, Higuchi A, Alarfaj AA, Munusamy MA, Kumar S, Desneux N, Benelli G (2016) Fern-synthesized nanoparticles in the fight against malaria: LC/MS analysis of Pteridium aquilinum leaf extract and biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles with high mosquitocidal and antiplasmodial activity. Parasitol Res 115:997–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4828-x

Radhakrishnan VS, Dwivedi SP, Siddiqui MH, Prasad T (2018) In vitro studies on oxidative stress-independent, ag nanoparticles-induced cell toxicity of Candida albicans, an opportunistic pathogen. Int J Nanomedicine 13:91–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S125010

Rahimi MT, Ahmadpour E, Rahimi Esboei B, Spotin A, Kohansal Koshki MH, Alizadeh A, Honary S, Barabadi H, Ali Mohammadi M (2015) Scolicidal activity of biosynthesized silvernanoparticles against Echinococcus granulosusprotoscolices. Int J Surg 19:128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.05.043

Rai M, Ingle AP, Paralikar P, Gupta I, Medici S, Santos CA (2017) Recent advances in use of silvernanoparticles as antimalarial agents. Int J Pharm 526:254–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.04.042

Roy P, Saha SK, Gayen P, Chowdhury P, Sinha Babu SP (2017) Exploration of antifilarial activity of gold nanoparticle against human and bovine filarial parasites: a nanomedicinal mechanistic approach. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces 161:236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.10.057

Saad HA, Soliman MI, Azzam AM, Mostafa B (2015) Antiparasitic activity of silver and copper oxide nanoparticles against Entamoeba histolytica and Cryptosporidium parvum cysts. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 45:593–602. https://doi.org/10.12816/0017920

Said DE, Elsamad LM, Gohar YM (2012) 2012 validity of silver, chitosan, and curcumin nanoparticles as anti-Giardia agents. Parasitol Res 111(2):545–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-012-2866-1

Scalbert A (1989) Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochemistry 30:3875–3883. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(91)83426-l

Scheid P (2007) Mechanism of intrusion of a microspordian-like organism into the nucleus of host amoebae (Vannella sp.) isolated from a keratitis patient. Parasitol Res 101:1097–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-007-0590-z

Scheikl U, Tsao HF, Horn M, Indra A, Walochnik J (2016) Free-living amoebae and their associated bacteria in Austrian cooling towers: a 1-year routine screening. Parasitol Res 115:3365–3374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-016-5097-z

Shahverdi AR, Fakhimi A, Shahverdi HR, Minaian S (2007) Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomedicine 3:168–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2007.02.001

Sondi I, Salopek-Sondi B (2004) Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E.coli as a model for gram-negative bacteria. J Colloid Interface Sci 275:177–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-46152-8.00019-6

Ullah I, Cosar G, Abamor ES, Bagirova M, Shinwari ZK, Allahverdiyev AM (2018) Comparative study on the antileishmanial activities of chemically and biologically synthesized silvernanoparticles (AgNPs). 3 Biotech 8:98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1121-6

Urbańska K, Pająk B, Orzechowski A, Sokołowska J, Grodzik M, Sawosz E, Szmidt M, Sysa P (2015) The effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on proliferation and apoptosis of in ovo cultured glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-0823-5

Walochnik J, Scheikl U, Haller-Schober EM (2015) Twenty years of Acanthamoeba diagnostics in Austria. J Eukaryot Microbiol 62:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12149

Willcox MD, Hume EB, Vijay AK, Petcavich R (2010) Ability of silver-impregnated contact lenses to control microbial growth and colonization. J Opt 3:143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1888-4296(10)70020-0

Yan X, He B, Liu L, Qu G, Shi J (2018) Antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: proteomics approach. Metallomics 10:557–564. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7mt00328e

Zielinska M, Sawosz E, Grodzik M, Wierzbicki M, Gromadka M, Hotowy A, Sawosz F, Lozicki A, Chwalibog A (2011) Effect of heparan sulfate and gold nanoparticles on muscle development during embryogenesis. Int J Nanomedicine 6:3163–3172. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s26070

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Jarosław Szczepaniak, MSc and Krzysztof Pionkowski, MSc for their help in TEM image preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Padzik, M., Hendiger, E.B., Chomicz, L. et al. Tannic acid-modified silver nanoparticles as a novel therapeutic agent against Acanthamoeba. Parasitol Res 117, 3519–3525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-6049-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-6049-6