Abstract

Purpose

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) survivors experience increased risk of medical and neurodevelopmental challenges. This study describes the health-related quality of life (HRQOL), special education utilization and the family impact among neonatal CDH survivors.

Methods

A single-center prospective cohort of CDH survivors born between 1995 and 2006 was followed. Parents completed the PedsQL HRQOL index and a Family Impact survey to assess the need for medical equipment, home health services, and special education and quantify the burden placed on the family by their child’s medical needs.

Results

Parents of 32 survivors participated at a mean survivor age of 8 ± 4 years. Many survivors utilized medical equipment (62%), home health services (18%) and special education (28%). CDH survivor HRQOL (79 ± 17) did not differ significantly from that of healthy children (83 ± 15, p = 0.12). HRQOL was diminished among survivors who required special education (67 ± 8 vs 82 ± 3; p = 0.04) and those reporting increased Family Impact score (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Many CDH survivors continue to require home medical equipment and home health services at school age. Most survivors have normal parent-reported HRQOL; however, the need for special education and higher family impact of neonatal CDH correlates with decreased HRQOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a complex perinatal condition requiring multidisciplinary evaluation and management. Treatment requires comprehensive neonatal intensive care, including mechanical ventilation, total parenteral nutrition, administration of analgesics and sedatives, neonatal surgery and, at times, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). CDH survivors demonstrate that this group is at high risk for long-term neurologic, pulmonary, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal compromise [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Many CDH survivors may do well; however, a subset experiences recurrent hospitalization, physical and cognitive limitation, recurrent respiratory illness and failure to thrive. Survivors often require chronic medications and need home medical equipment, including feeding tubes, oxygen, and ventilator support [8,9,10]. The impact of CDH sequelae on the child’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL), educational needs and the impact on the family has not been well described.

Patients, families, and providers may benefit from improved understanding of the long-term consequences of CDH survivorship [11]. Treatment advances have improved survival of neonates with very severe CDH, resulting in increased prevalence of health compromise in CDH survivors [12, 13]. Furthermore, improved prenatal diagnosis and increased parental participation in medical decision-making have increased the need for improved long-term outcome information to inform these conversations. The objective of this study was to evaluate HRQOL, educational outcomes and family impact in survivors of CDH.

Methods

This single-center, prospective cohort study of neonates with CDH born between 1995 and 2006 and managed at a regional children’s hospital was approved by the institutional review board. Parents of eligible children were approached in hospital clinics, by telephone and through postal mail for study participation with data collected between 2006 and 2014. Children aged 7–13 years provided assent to participate, and those over the age of 14 years provided written consent with their parents. Data abstracted from the hospital medical record included demographic and clinical information such as delivery records, lab results, operative details and length-of-stay information.

PedsQL© version 4.0, a validated parent-proxy measure of HRQOL, was administered to participating parents [14]. The two-page survey utilizes parent report to assess quality of life on a five-point scale in four domains: physical, emotional, school and social. The survey is modified for age, with separate inventories for toddlers (ages 2–4 years), young children (ages 5–7 years), children (ages 8–12 years) and teens (ages 13–18 years). The self-identified main caregiver for each child completed the age-appropriate PedsQL© parent-proxy form. Normative values for large samples of healthy subjects completing PedsQL© are available for comparison [14].

We developed a Family Impact Questionnaire to assess the effect of long-term CDH care on the family. The questionnaire collected information regarding family composition, patient educational status, medical equipment utilized, and family burden resulting from the child’s illness. The six family burden questions were answered on a five-point Likert scale; the mean score was calculated as a Family Impact score. The self-identified main caregiver for each CDH survivor completed the Family Impact Questionnaire.

STATA SE 14 was utilized for statistical analysis. Total count and proportion were reported for categorical variables and analyzed using Chi square and multivariate logistic regression. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables and analyzed using t tests and multivariate linear regression. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

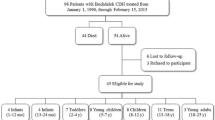

One hundred and nineteen neonates were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit with a CDH during the study period. Of these, 88 survived to discharge and 32 were enrolled in the study at a mean age of 8 ± 4 years. Of the 56 survivors who did not enroll, three declined, nine enrolled but did not complete the questionnaires and 44 could not be contacted at the address noted in the medical record. Cohort demographic and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics differed between study participants and nonparticipants. Non-participants were repaired at an earlier age and had less need for discharge with tube feedings.

HRQOL of CDH survivors

All 32 CDH survivors enrolled in the study required intubation within first 6 h of life, 28 (90%) had a left CDH, 9 (32%) had liver in the chest, 3 (9%) had an associated major anomaly and 6 (19%) required a chest tube for a preoperative pneumothorax. Of the 32 parents completing the PedsQL© measure, five (16%) filled out the Toddler version, 12 (38%) filled out the Young Child version, 9 (28%) filled out the Child version and 6 (19%) filled out the Teen version. There were no differences in quality of life between age groups. The mean HRQOL score, on a scale of 100, was 79 ± 17, which did not differ from the healthy population mean of 83 ± 15 (p = 0.12) [14]. Table 2 presents comparison of PedsQL sub-scores between the study population and normative population. Compared to normative population, physical sub-scores were higher, 95 ± 10 vs 80 ± 18 (p = 0.0001), while school performance sub-scores were lower, 64 ± 25 vs 76 ± 20 (p = 0.002), in the study population. There was no difference in emotional or social sub-scores.

Eight (25%) participants reported mean composite PedsQL scores of ≤ 68, which indicates impaired quality of life due to a chronic disease [14]. Our center reported increased mortality in infants with CDH whose initial pCO2 was greater than 80 mmHg [15]. In this study, three participants had initial pCO2 greater than 80 mmHg, none of whom reported HRQOL in the impaired category. Of other clinical characteristics analyzed (Table 3), including gestational age, birth weight, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), side of hernia, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay and home supply use at the time of survey, only lack of prenatal diagnosis was associated with diminished quality of life (62% of the diminished HRQOL group vs 56% of the normal HRQOL group, p < 0.03).

Family impact of caring for a CDH survivor

In the cohort surveyed, 62% of survivors required home medical equipment, 28% received special education and 18% utilized home health services. Figure 1 shows that the HRQOL decreased in CDH survivors if they needed special education, 68 ± 82 vs 82 ± 27 (p = 0.04). The medical equipment used at home included nebulizers (n = 14, 44%), feeding tubes (n = 7, 22%), eyeglasses (n = 5, 16%), wheelchairs (n = 3, 9%) and home ventilators (n = 2, 6%). The Family Impact score was reported on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater impact (Table 4). Figure 2 shows that the HRQOL decreased in CDH survivors as the Family Impact score increased (R2 = 0.33, p = 0.04).

Discussion

At school age, the majority of CDH survivors have parent-reported HRQOL comparable to their healthy peers. The need for special education and increased family impact is associated with decreased HRQOL. At school age, a third of CDH survivors surveyed continue to need a home ventilator and/or feeding tube and a quarter require special education. Understanding the potential long-term medical, educational, and social aspects of CDH by both parents and providers is important in developing prognosis and expected long-term outcomes.

We found the need for special education in this cohort is consistent with the reported 30% incidence of learning difficulties among CDH survivors [16]. We do not have information regarding the reason for the need for special education for the study cohort. In the United States, this determination is made by parents in collaboration with a team of teaching professionals qualified to teach a child of his/her age. Special education requirements among CDH survivors are double the reported prevalence for children in the state of Wisconsin [17]. However, this finding is not surprising given the rates of neurologic compromise reported among preschool and early school-aged CDH survivors [18]. Beyond the burden placed on the child and the family, the need for special education also represents a significant societal cost. From 2000 to 2001, Wisconsin school districts spent one billion dollars to educate and otherwise serve the state’s 125,358 students enrolled in special education [19]. Improved understanding of educational outcomes for CDH survivors may allow for planning and earlier intervention.

Most CDH follow-up studies focus on physical morbidity rather than psychosocial outcomes such as HRQOL, which encompasses physical, emotional, social and school functioning. Poley et al. evaluated HRQOL for 111 CDH survivors and found that HRQOL improved with age and reached normal levels in adulthood despite many survivors continuing to be symptomatic from CDH sequelae [20]. Peetsold et al. found HRQOL to be normal in their cohort of 33 CDH survivors between the ages of 6 and 16 years [16]. In contrast, Michel et al. found HRQOL to be lower in 32 CDH survivors compared to controls [21]. Our study demonstrates significant decrease in HRQOL for the subset of CDH survivors requiring special education and those with elevated Family Impact scores. While overall HRQOL in CDH survivors is comparable to that of healthy children in our study, school performance sub-scores were lower, consistent with increased likelihood of receiving special education. These data provide increased description of the risks for impaired HRQOL and detail sub-score differences in CDH survivors. Interestingly, CDH survivors had increased physical sub-scores compared to the healthy population. Other investigators have also found that disabled teenagers and their caregivers report a higher HRQOL compared to healthy controls. It is postulated that this phenomenon is due to the affected population learning to accept their disabilities and having recalibrated their personal expectations [22].

The Family Impact score shows that most parents report fairly low burden secondary to their child’s illness; however, 68% report often or always worrying about their child due to the health condition. Chen et al. evaluated the family impact of CDH in a cohort of 52 CDH survivors with a median age of 8 years, reporting increased impact on the family for survivors who had a more severe clinical course and persistent medical problems [13]. While the Family Impact scores reported here did not correlate with illness severity, increased Family Impact scores correlated with decreased HRQOL.

This single-institution study is limited by the modest sample size. Relying on hospital record contact information made it difficult to establish contact with 44 of the CDH survivors. Study participants differed significantly from nonparticipants with regard to repair age and need for tube feedings at discharge. Our sample has higher representation of CDH follow-up clinic patients, which may bias our findings to reflect survivors that require more medical support. The ad hoc Family Impact Questionnaire was specifically developed for use in this study without previous validation. Despite these limitations, the findings are consistent with and expand upon other reports in the literature.

This cross-sectional prospective study of school-aged CDH survivors describes HRQOL, educational and family outcomes. HRQOL in children with CDH does not differ from healthy children. CDH survivors are, however, twice as likely to require special education, and those receiving special education report lower HRQOL at school age. Family impact varies greatly, but most children with CDH require home medical supplies when at school age, and parent-reported HRQOL decreases as family impact increases. These descriptions of long-term HRQOL, educational and family outcomes in children with CDH may improve prenatal counseling, prognostication and family support.

References

Trachsel D, Selvadurai H, Bohn D, Langer JC, Coates AL (2005) Long-term pulmonary morbidity in survivors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Pulmonol 39:433–439

Haliburton B, Mouzaki M, Chiang M, Scaini V, Marcon M, Moraes TJ, Chiu PP (2015) Long-term nutritional morbidity for congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors: failure to thrive extends well into childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr Surg 50(5):734–738

Danzer E, Hoffman C, D’Agostino JA, Gerdes M, Bernbaum J, Antiel RM, Rintoul NE, Herkert LM, Flake AW, Adzick NS, Hedrick HL (2017) Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 5 years of age in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 52(3):437–443

Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Wilder RT, Voigt RG, Olson MD, Sprung J, Weaver AL, Schroeder DR, Warner DO (2011) Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics 128(5):E1053–E1061

Bevilacqua F, Morini F, Zaccara A, Valfre L, Capolupo I, Bagolan P, Aite L (2015) Neurodevelopmental outcome in congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors: role of ventilator time. J Pediatr Surg 50:394–398

Cauley RP, Stoffan A, Potanos K, Fullington N, Graham DA, Finkelstein JA, Bairdain S, Kim HB, Wilson JM (2013) Pulmonary support on day of life 30 as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 48(6):1183–1189

Damzer E, Gerdes M, D’Agostino JA, Bernbaum J, Hoffman C, Herkert L, Rintoul NE, Peranteau WH, Flake AW, Adzick NS, Hedrick HL (2015) Neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age in congenital diaphragmatic hernia infants not treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg 50(6):898–903

Bagolan P, Morini F (2007) Long-term follow up of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg 16(2):134–144

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on, Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and, Newborn Lally KP, Engle W (2008) Postdischarge follow-up of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics 121(3):627–632

Downard CD, Wilson JM (2003) Current therapy of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Neonatol 8(3):215–221

Kemp J, Davenport M, Pernet A (1998) Antenatally diagnosed surgical anomalies: the psychological effect of parental antenatal counseling. J Pediatr Surg 33(9):1376–1379

Chiu PPL, Sauer C, Mihailovic A et al (2006) The price of success in the management of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Is improved survival accompanied by an increase in long-term morbidity? J Pediatr Surg 41(5):888–892

Chen C, Jeruss S, Terrin N, Tighiouart H, Wilson JM, Parsons SK (2007) Impact on family of survivors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: a pilot study. J Pediatr Surg 42:1845–1852

Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM (2007) Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities using the PedsQL 4.0 generic core scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 5(43):1–15

Khmour AY, Konduri GG, Sato TT, Uhing MR, Basir MA (2014) Role of admission gas exchange measurement in predicting congenital diaphragmatic hernia survival in the era of gentle ventilation. J Pediatr Surg 49(8):1197–1201

Peetsold MG, Huisman J, Hofman VE, Heij HA, Raat H, Gemke RJ (2009) Psychological outcome and quality of life in children born with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Arch Dis Child 94:834–840

Hruz T (2002) The growth of special education in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, Thiensville

Benjamin JR, Gustafson KE, Smith PB et al (2013) Perinatal factors associated with poor neurocognitive outcome in early school age congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors. J Pediatr Surg 48(4):730–737

Hruz T (2002) Wisconsin Policy Research Institute Report, vol 15, number 5. http://www.wpri.org/WPRI-Files/Special-Reports/Reports-Documents/Vol15no5.pdf. Accessed 10 Nov 2018

Poley MJ, Stolk EA, Tibboel D, Molenaar JC, Busschbach JJV (2004) Short term and long term health related quality of life after congenital anorectal malformations and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Arch Dis Child 89(9):836–841

Michel F, Baumstarck K, Gosselin A et al (2013) Health-related quality of life and its determinants in children with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8:89

Saigal S, Feeny D, Rosenbaum P et al (1996) Self-perceived health status and health-related quality of life of extremely low-birth-weight infants at adolescence. J Am Med Assoc 276(6):453–459

Funding

Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fritz, K.A., Khmour, A.Y., Kitzerow, K. et al. Health-related quality of life, educational and family outcomes in survivors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg Int 35, 315–320 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-018-4414-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-018-4414-2