Abstract

Objective

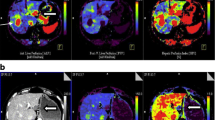

To evaluate morphological and perfusion changes in liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumours by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) after transarterial embolisation with bead block (TAE) or trans-arterial chemoembolisation with doxorubicin-eluting beads (DEB-TACE).

Methods

In this retrospective study, seven patients underwent TAE, and ten underwent DEB-TACE using beads of the same size. At 1 day before embolisation, 2 days, 1 month and 3 months after the procedure, a destruction-replenishment study using CEUS was performed with a microbubble-enhancing contrast material on a reference tumour. Relative blood flow (rBF) and relative blood volume (rBV) were obtained from the ratio of values obtained in the tumour and in adjacent liver parenchyma. Morphological parameters such as the tumour’s major diameter and the viable tumour’s major diameter were also measured. A parameter combining functional and morphological data, the tumour vitality index (TVI), was studied. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s test were used to compare treatment groups.

Results

At 3 months rBF, rBV and TVI were significantly lower (P = 0.005, P = 0.04 and P = 0.03) for the group with doxorubicin. No difference in morphological parameters was found throughout the follow-up.

Conclusions

One parameter, TVI, could evaluate the morphological and functional response to treatments.

Key Points

• Contrast-enhanced ultrasound provides morphological and functional information about neuroendocrine hepatic metastases

• CEUS can evaluate changes after transarterial chemoembolisation, transarterial-embolisation and transarterial radioembolisation

• Functional (but not morphological) imaging reveals differences between TAE and DEB-TACE therapy

• To combine morphological and functional parameters, a tumour vitality index is proposed

• TVI can be used to monitor treatments acting on tumour vascularisation

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- BF:

-

blood flow

- BV:

-

blood volume

- CEUS:

-

contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- CHI:

-

contrast harmonic imaging

- CR:

-

complete response

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DEB:

-

drug-eluting beads

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- MI:

-

mechanical index

- NET:

-

neuroendocrine tumour

- rBF:

-

relative blood flow

- rBV:

-

relative blood volume

- PD:

-

progressive disease

- PR:

-

partial response

- RECIST:

-

response evaluation criteria in solid tumours

- ROI:

-

region of interest

- SD:

-

stable disease

- TACE:

-

trans-arterial chemoembolisation

- TAE:

-

trans-arterial embolisation

- TVI:

-

tumour vitality index

- TMD:

-

tumour’s major diameter

- VTMD:

-

viable tumour’s major diameter

- WDEC:

-

well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma

References

Vogl TJ, Naguib NN, Zangos S, Eichler K, Hedayati A, Nour-Eldin NE (2009) Liver metastases of neuroendocrine carcinomas: interventional treatment via transarterial embolization, chemoembolization and thermal ablation. Eur J Radiol 72:517–528

Walter T, Brixi-Benmansour H, Lombard-Bohas C, Cadiot G (2012) New treatment strategies in advanced neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Liver Dis 44:95–105

Dominguez S, Denys A, Madeira I et al (2000) Hepatic arterial chemoembolization with streptozotocin in patients with metastatic digestive endocrine tumours. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:151–157

Jordan O, Denys A, De Baere T, Boulens N, Doelker E (2010) Comparative study of chemoembolization loadable beads: in vitro drug release and physical properties of DC bead and hepasphere loaded with doxorubicin and irinotecan. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21:1084–1090

Lee KH, Liapi EA, Cornell C et al (2010) Doxorubicin-loaded QuadraSphere microspheres: plasma pharmacokinetics and intratumoral drug concentration in an animal model of liver cancer. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 33:576–582

Ohta S, Nitta N, Sonoda A et al (2009) Prolonged local persistence of cisplatin-loaded gelatin microspheres and their chemoembolic anti-cancer effect in rabbits. Eur J Radiol 72:534–540

Kettenbach J, Stadler A, Katzler IV et al (2008) Drug-loaded microspheres for the treatment of liver cancer: review of current results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 31:468–476

Namur J, Wassef M, Millot JM, Lewis AL, Manfait M, Laurent A (2011) Drug-eluting beads for liver embolization: concentration of doxorubicin in tissue and in beads in a pig model. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21:259–267

Malagari K, Alexopoulou E, Chatzimichail K et al (2008) Transcatheter chemoembolization in the treatment of HCC in patients not eligible for curative treatments: midterm results of doxorubicin-loaded DC bead. Abdom Imaging 33:512–519

Lewis AL, Gonzalez MV, Leppard SW et al (2007) Doxorubicin eluting beads—1: effects of drug loading on bead characteristics and drug distribution. J Mater Sci Mater Med 18:1691–1699

Nicolini A, Martinetti L, Crespi S, Maggioni M, Sangiovanni A (2010) Transarterial chemoembolization with epirubicin-eluting beads versus transarterial embolization before liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21:327–332

Dhanasekaran R, Kooby DA, Staley CA, Kauh JS, Khanna V, Kim HS (2010) Comparison of conventional transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and chemoembolization with doxorubicin drug eluting beads (DEB) for unresectable hepatocelluar carcinoma (HCC). J Surg Oncol 101:476–480

de Baere T, Deschamps F, Teriitheau C et al (2008) Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases from well differentiated gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors with doxorubicin-eluting beads: preliminary results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 19:855–861

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA et al (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216

Forner A, Ayuso C, Varela M et al (2009) Evaluation of tumor response after locoregional therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma: are response evaluation criteria in solid tumors reliable? Cancer 115:616–623

Varela M, Real MI, Burrel M et al (2007) Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: efficacy and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics. J Hepatol 46:474–481

Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM et al (2001) Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL Conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol 35:421–430

Memon K, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ et al (2011) Radiographic response to locoregional therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts patient survival times. Gastroenterology 141:526–535, 535 e521-522

Rosen MA, Schnall MD (2007) Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for assessing tumor vascularity and vascular effects of targeted therapies in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 13:770s–776s

Miles KA (2003) Perfusion CT for the assessment of tumour vascularity: which protocol? Br J Radiol 76:S36–S42

Padhani A (2006) PET imaging of tumour hypoxia. Cancer Imaging 6:S117–S121

Rindi G, Kloppel G, Couvelard A et al (2007) TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch 451:757–762

Bouvier A, Ozenne V, Aube C et al (2011) Transarterial chemoembolisation: effect of selectivity on tolerance, tumour response and survival. Eur Radiol 21:1719–1726

Malagari K, Pomoni M, Kelekis A et al (2009) Prospective randomized comparison of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-eluting beads and bland embolization with BeadBlock for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 33:541–551

Zachary JF, Blue JP, Miller RJ, O’Brien WD Jr (2006) Vascular lesions and s-thrombomodulin concentrations from auricular arteries of rabbits infused with microbubble contrast agent and exposed to pulsed ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol 32:1781–1791

Guibal A, Taillade L, Mule S et al (2011) Noninvasive contrast-enhanced US quantitative assessment of tumor microcirculation in a murine model: effect of discontinuing anti-VEGF therapy. Radiology 254:420–429

Lefort T, Pilleul F, Mule S et al (2012) Correlation and agreement between contrast-enhanced ultrasonography and perfusion computed tomography for assessment of liver metastases from endocrine tumors: normalization enhances correlation. Ultrasound Med Biol 38:953–961

Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S (1998) Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation 97:473–483

Krix M, Plathow C, Essig M et al (2005) Monitoring of liver metastases after stereotactic radiotherapy using low-MI contrast-enhanced ultrasound–initial results. Eur Radiol 15:677–684

Riaz A, Miller FH, Kulik LM et al (2010) Imaging response in the primary index lesion and clinical outcomes following transarterial locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA 303:1062–1069

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247

Guiu B, Deschamps F, Aho S et al (2012) Liver/biliary injuries following chemoembolisation of endocrine tumours and hepatocellular carcinoma: lipiodol vs. drug-eluting beads. J Hepatol 56:609–617

Moschouris H, Malagari K, Kornezos I, Papadaki MG, Gkoutzios P, Matsaidonis D (2010) Unenhanced and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography during hepatic transarterial embolization and chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 33:1215–1222

Riaz A, Memon K, Miller FH et al (2011) Role of the EASL, RECIST, and WHO response guidelines alone or in combination for hepatocellular carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. J Hepatol 54:695–704

Krix M, Plathow C, Kiessling F et al (2004) Quantification of perfusion of liver tissue and metastases using a multivessel model for replenishment kinetics of ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound Med Biol 30:1355–1363

Browder T, Butterfield CE, Kraling BM et al (2000) Antiangiogenic scheduling of chemotherapy improves efficacy against experimental drug-resistant cancer. Cancer Res 60:1878–1886

Gupta S, Kobayashi S, Phongkitkarun S, Broemeling LD, Kan Z (2006) Effect of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization on angiogenesis in an animal model. Invest Radiol 41:516–521

Liao XF, Yi JL, Li XR, Deng W, Yang ZF, Tian G (2004) Angiogenesis in rabbit hepatic tumor after transcatheter arterial embolization. World J Gastroenterol 10:1885–1889

Feingold S, Gessner R, Guracar IM, Dayton PA (2010) Quantitative volumetric perfusion mapping of the microvasculature using contrast ultrasound. Invest Radiol 45:669–674

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: the monoexponential refilling model (CEUS with destruction-replenishment sequence—general case)

Appendix: the monoexponential refilling model (CEUS with destruction-replenishment sequence—general case)

During constant infusion of microbubbles, the regional concentration of refilling microbubbles after destruction can be described by the following equations according to the indicator-dilution theory with single open-compartment analysis:

where C0 is the regional concentration of microbubbles within the microcirculation outside the ultrasound field (quantity of microbubbles/100 g of tissue), F the regional blood flow (ml/min/100 g of tissue) and Vf the fractional blood volume (ml/100 g of tissue) (43). Considering that at time t = 0, C(t) = 0, the solution of Eq. (A1) is:

with β = F/Vf.

In the infusion conditions the concentration of microbubbles in the blood, Ci, is constant within the vascular space. Therefore, as C0 = Vf∙Ci, the plateau of the curve given by Eq. (A2), C0, is proportional to the fractional blood volume Vf.

The slope of the curve given by Eq. (A2) is given by:

; thus, the initial slope (t = 0) is C0β and is proportional to the blood flow F (26).

According to the central volume principle, mean vascular transit time = blood volume/blood flow (44); thus the value 1/β can be considered as an estimation of the regional mean transit time of microbubbles.

At the concentrations used in clinical CEUS practice, the signal intensity I is proportional to the concentration in microbubbles in the image (26); thus Eq. (A2) becomes:

with I(t) = k∙C(t) and A = k∙C0.

Considering tumoral and parenchymal ROIs in the same ultrasound field, the ratio of the initial signal intensity slopes (A∙β) equals the ratio of regional blood flow values, the ratio of the signal plateaus (A) equals the ratio of the regional fractional blood volumes, and the ratio of the 1/β values is an estimation of the ratio of the regional mean transit time values.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guibal, A., Lefort, T., Chardon, L. et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound after devascularisation of neuroendocrine liver metastases: functional and morphological evaluation. Eur Radiol 23, 805–815 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2646-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2646-4