Abstract

Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) is a brominated flame retardant (BFR) that accumulates in humans and affects the nervous system. To elucidate the mechanisms of HBCD neurotoxicity, we used transcriptomic profiling in brains of female mice exposed through their diet to HBCD (199 mg/kg body weight per day) for 28 days and compared with those of neuronal N2A and NSC-19 cell lines exposed to 1 or 2 µM HBCD. Similar pathways and functions were affected both in vivo and in vitro, including Ca2+ and Zn2+ signalling, glutamatergic neuron activity, apoptosis, and oxidative stress. Release of cytosolic free Zn2+ by HBCD was confirmed in N2A cells. This Zn2+ release was partially quenched by the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine indicating that, in accordance with transcriptomic analysis, free radical formation is involved in HBCD toxicity. To investigate the effects of HBCD in excitable cells, we isolated mouse hippocampal neurons and monitored Ca2+ signalling triggered by extracellular glutamate or zinc, which are co-released pre-synaptically to trigger postsynaptic signalling. In control cells application of zinc or glutamate triggered a rapid rise of intracellular [Ca2+]. Treatment of the cultures with 1 µM of HBCD was sufficient to reduce the glutamate-dependent Ca2+ signal by 50%. The effect of HBCD on zinc-dependent Ca2+ signalling was even more pronounced, resulting in the reduction of the Ca2+ signal with 86% inhibition at 1 µM HBCD. Our results show that low concentrations of HBCD affect neural signalling in mouse brain acting through dysregulation of Ca2+ and Zn2+ homeostasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

1,2,5,6,9,10-Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) is a brominated flame retardant (BFR), mainly used in thermal insulation foams in building and construction, as well as in plastics and textiles. High quantities were used due to bans on many other BFRs, especially in Europe (Birnbaum and Staskal 2004; Chain EPoCitF 2012; Law et al. 2005). In 2013 HBCD was listed in Annex A (POP for elimination) under the Stockholm convention on persistent organic pollutants (POPs), with specific exceptions. Namely, HBCD can be still produced and used for expanded polystyrene and extruded polystyrene in buildings.

HBCD has been detected in the environment worldwide. It has been found in samples of urban and rural air (Covaci et al. 2006; Vorkamp et al. 2012), soil (Drage et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016a), water (de Wit et al. 2010), and household dust (de Wit et al. 2012; Schreder and La Guardia 2014). HBCD is a lipophilic compound (log K ow = 5.81) (American Chemistry Council 2001) that bioaccumulates through food webs, and concentrations are particularly high in oily fish, such as salmon (Chain EPoCitF 2012; Fromme et al. 2016). The main sources of human exposure to HBCD are contaminated food, breast milk, and inhalation from polluted indoor dust and air (Chain EPoCitF 2012; Fromme et al. 2016). Presence of HBCD in human breast milk has been identified in samples from various countries including Canada, United States, Europe and China. HBCD concentrations in breast milk increased from 1980 to 2002, but have reached a stable level since (Eljarrat et al. 2009; Fängström et al. 2008; Ryan and Rawn 2014; Shi et al. 2013). HBCD has been also measured in human serum (Rawn et al. 2014b; Roosens et al. 2009) and human foetal liver and placental tissues (Rawn et al. 2014a).

HBCD has the potential to cause histological changes in liver, thymus and thyroid (Maranghi et al. 2013; van der Ven et al. 2006). It can induce adverse effects to the reproductive, endocrine, and central nervous systems (Chain EPoCitF 2012; Maranghi et al. 2013; Rasinger et al. 2014; van der Ven et al. 2006, 2009). Notably, 28-day oral exposure to HBCD increased thyroid weight and activity of the thyroxine (T4) metabolising enzyme T4-UGT, and decreased total circulating thyroxin in female Wistar rats (van der Ven et al. 2006). These effects are accompanied by evidence of suppressed thyroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription (Ibhazehiebo et al. 2011). Along with effects on the thyroid hormone system, the most sensitive end-points in animal studies have related to neurodevelopment (Chain EPoCitF 2012).

Due to its lipophilicity, HBCD can pass the blood brain barrier (BBB) and accumulate in the brain (Covaci et al. 2006; Rasinger et al. 2014). Its ability to cause neurotoxicity has been evidenced by developmental behavioural effects seen after exposure (Eriksson et al. 2006; Lilienthal et al. 2009). In mice exposed to HBCD, effects on memory and learning have been reported at single oral doses between 0.9 and 13.5 mg/kg body weight (Eriksson et al. 2006), and in rats exposed to HBCD, effects on dopamine-dependent behaviour and hearing function were observed (Lilienthal et al. 2009). These effects may be related to a reduction in expression of the striatal dopamine transporter and vesicular monoamine transporter 2, as observed in studies in C57BL/6J mice (Genskow et al. 2015). However, HBCD has also been shown to inhibit dopamine uptake with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 4 µM (Mariussen and Fonnum 2003). In the same study HBCD was also seen to inhibit glutamate uptake at concentrations as low as 1 µM, but it never achieved more than 50% inhibition (Mariussen and Fonnum 2003). In addition, accumulation of xenobiotics in the brain has been seen to cause a chronic inflammatory response which has been found to be linked with neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson diseases (DeLegge and Smoke 2008). In vivo studies in mice have shown that while exposure to BFRs during gestation may lead to congenital effects (Curran et al. 2011), later exposure during brain development can cause disturbed spontaneous behaviour in adults (Alm et al. 2008; Eriksson et al. 2006; Viberg et al. 2003).

In spite of the valuable information on the effects of HBCD on dopaminergic and glutamatergic neuronal function, knowledge of intracellular signalling pathways modulated by HBCD in neurons is limited. One such mechanism is likely interference with cellular Ca2+ homeostasis that is crucial for learning and memory function. HBCD (2–200 nM) was reported to reduce cytosolic free Ca2+ concentrations and increase Ca2+ content of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in rat H9C2 cardiomyocyte cell line (Wu et al. 2016b). In PC12 cells, 2 µM HBCD inhibited depolarisation-evoked [Ca2+]i transients and associated catecholamine release (Dingemans et al. 2009). HBCD also inhibited the sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells through interference with its ATP binding at an IC50 of 2.7 µM (Al-Mousa and Michelangeli 2014). As both pre- and post-synaptic events are dependent on Ca2+ signalling, this mechanism of action could have widespread consequences for neuronal function.

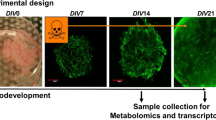

We sought to take an unbiased approach to explore molecular events leading to neurotoxicity of HBCD in mouse, integrating in vivo and in vitro experiments. This allowed us to explore mechanisms of action indicated in the animal experiment and to differentiate between direct effects of HBCD on the brain from potential indirect endocrine effects, caused by disruption of sex steroids (Rasinger et al. 2014) and thyroid hormones (van der Ven et al. 2006). We used transcriptomics to interrogate HBCD responses on gene expression in mouse brain in vivo as well as in two neuronally derived mouse cell lines, N2A and NSC19. Post-transcriptomics hypothesis driven experimentation on cell lines and isolated primary hippocampal cells demonstrated pronounced HBCD disruption of Ca2+ and Zn2+ homeostasis.

Materials and methods

Animal experiment, tissue sampling and HBCD analysis

Juvenile female BALB/c mice (n = 12, average weight 13–15 g) were purchased from Charles River (UK). A total of six mice (3 mice per cage) were exposed to a nominal dose of 199 mg/kg body weight per day HBCD through the diet; another six mice were fed an un-spiked control diet. The animal experiment was carried out under a project licence in accordance with the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and was performed as previously described by us (Maranghi et al. 2013; Rasinger et al. 2014). The experimental diet used was in accordance with the standard rodent diet formulation AIN-93 G with the exception that freeze-dried Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) was used as the main protein and fat source. The salmon used in the present work was raised specifically for the study on plant and vegetable oil substituted fish feed, which yielded exceptionally low background levels of contaminants in the fish (Berntssen et al. 2010). A technical mixture of HBCD (1.3 g/kg feed, purity: 99.2%; Applied Biosystems, UK) was dissolved and diluted in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and mixed into the feed at a concentration of 1.3 mg/kg feed. The control diet was adjusted to the same final DMSO content (0.4 mL/kg feed) as the HBCD spiked feed. This dietary concentration resulted in a daily dose of 199 mg/kg body weight and was in an identical experiment found to give an accumulation of HBCD within the brain tissue of 4.7 µg/g dry weight (Rasinger et al. 2014), which on a wet weight basis corresponds to approximately 7.3 µmol/kg. This dose did not affect feed consumption or weight gain and there were no overt changes in behaviour (data not shown). After 28 days of exposure, brains were sampled and prepared for analysis as described before (Rasinger et al. 2014). In short, the whole brain was excised from the cranial cavity and dissected on ice. Left cortices were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in a liquid nitrogen cooled mortar and pestle. Frozen powdered tissue was then partitioned in aliquots and stored at − 80 °C.

RNA extraction and transcriptomic analysis of murine juvenile brains

Total RNA was extracted from powdered brain tissue of HBCD exposed and control mice (n = 6 per group) as described by us before (Rasinger et al. 2014). In short, total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, USA) and the Qiagen RNeasy-Mini kit (Qiagen, Canada). RNA purity was assessed using a Nanodrop ND-100 UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, USA) and RNA quality and integrity were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer in combination with the RNA 6000 LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Gene expression microarray analysis was performed using GeneChip Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Array images were acquired using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix, USA). Array data were normalised using RMAsketch as implemented in the Affymetrix Expression Console.

Primary mouse hippocampal culture

Primary hippocampal cultures were obtained from postnatal P0-P2 days old mice that were anesthetised with isoflurane according to approved protocols. Hippocampi were removed and immediately placed in Hank’s balanced salt solution with HEPES (20 mM) and triturated in plating medium consisting of Neurobasal-A medium supplemented with 5% defined FBS, 2% B27, 2 mM Glutamax I, and 1 μg/mL gentamicin. Cells were then seeded on Poly-d lysine coated glass coverslips, in plating medium. 48 h following plating medium was replaced by serum-free culture medium that consisted of Neurobasal-A, 2 mM Glutamax I, and 2% B27.

Cell line culture

N2A and NSC19 cells were kindly provided by Prof. Joerg Bartsch (Philipps-Universität, Marburg, Germany). Both the cell lines were cultured in DMEM with 110 mg/sodium pyruvate, supplemented with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

MTT assay

To test the cytotoxicity of HBCD, cells were seeded into 96-well plates in 100 µL of DMEM. After 24 h of cell attachment, the cells were exposed to a series of HBCD concentrations. Serial stock solutions of HBCD were prepared in DMSO; the final concentration of DMSO in HBCD-containing medium was below 0.1%, which is well tolerated by neuroblastoma cells (Xia et al. 2008). Control wells received 0.1% DMSO only. To perform a (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, SIGMA, UK) colorimetric assay, cells seeded into 96-well plates (density: 1 × 104 cells/well) were exposed to HBCD at concentrations between 1.56 and 50 µM for 48 h. Following HBCD exposure, the medium was removed and 100 µL of the MTT salt diluted in fresh media at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL were added to each well. Cells were incubated for 4 h in incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, the MTT salt was replaced by 20 µL of DMSO to dissolve the purple formazan. The absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 570 nm. The background absorbance was measured at 650 nm and was subtracted from the first measurement.

Caspase-3 assay

Caspase-3 activity was measured as a marker of apoptosis using a commercial kit (Caspase-3 assay, Invitrogen, UK). Cells seeded into a 12-well plate (density of 1 × 106 cells/well) were exposed to HBCD at four different concentrations: 1, 2, 4 or 8 µM for 24 h. After HBCD treatments, cells were collected, washed twice with Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, GIBCO, UK) and the Caspase-3 assay was performed as per recommendations of the supplier.

Analysis of intracellular Zn2+

Free and loosely bound Zn2+ was detected in the neuroblastoma N2A cell line using the zinc-specific fluorescent dye Zynpyr-1 (Mellitech, France; K d = 0.7 ± 0.1 nM). Zinc assays were performed in cells grown in a 96-well plate, detecting the fluorescence with a fluorescence plate reader. Cells were exposed to HBCD at different concentrations for 24 h.

After treatments on coverslips or in a 96-well plate, cells were washed and kept moisturised with Ringer buffer (3 M NaCl, 2.7 M KCl, 0.8 M MgCl2, 2 M Hepes, 0.75 M glucose, 1.8 M CaCl2, calibrated to pH 7.4). Zinpyr-1 dye was diluted in PBS at a concentration of 16 µM. After exposure to the dye for 30 s, cells were washed with PBS for 30 s. The fluorescence was measured with the plate reader Thermo Scientific Fluoroskan Ascent at an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm. Fluorescence emission was normalized to the DMSO control in each row separately and the Zn2+-induced fluorescence expressed as fold-change relative to the control.

Specificity of the zinc signal was verified by pre-treatment (2 h) with the zinc chelator diethyldithiocarbamate (DEDTC, Sigma Aldrich) at 50 µM. Alternatively, cells were pre-treated with 10 µM of the zinc chelator and antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for 1 h. Activation of the NO pathway was investigated performing a 1 h treatment with 10 µM of the NO synthase blocker L-NAME before HBCD exposure.

Ca2+ imaging

The intracellular concentration of free Ca2+ was imaged in cultured primary hippocampal neural cells. Cultures were maintained for 9–12 days before imaging and then treated with HBCD at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. For intracellular Ca2+ measurements, cultures were loaded with Fura-2 AM (5 µM, 20 min) and fluorescent imaging was performed as described previously, using the ratio of the emission signal following excitation with 340 nm and 380 nm (Besser et al. 2009). Representative traces of fluorescent signal changes are presented. The initial rate of the response following addition of glutamate or Zn2+ was determined using a linear fit, and the averaged response of at least seven slides from three different cultures is presented in the bar graphs. Since the AM dye requires hydrolysis by intracellular esterases to remain within the cell, only live neurons accumulate Fura-2 and are used for the subsequent Ca2+—response analysis. To determine the survival of cells following HBCD treatments, representative cultures were washed following the 24 h treatment and mounting medium containing DAPI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was applied. Coverslips were observed using fluorescence microscope Axioscop 2 (Zeiss) with the appropriate filters at 10 × magnification.

RNA extraction and transcriptomic analysis of N2A and NSC19 cells

N2A and NSC19 cells were exposed to either 1 or 2 µM of HBCD, a DMSO control or a negative control (medium only). After 24 h exposure, total RNA was extracted and subjected to a custom two-colour microarray analysis (mouse OpArray, 4.0, Operon, USA) as detailed by us before (Rasinger et al. 2014). In brief, total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, USA) and the Qiagen RNeasy-Mini kit (Qiagen, Canada). RNA purity was assessed using a Nanodrop ND-100 UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, USA) and RNA quality and integrity were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer in combination with the RNA 6000 LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). A cDNA pool generated from a pool of RNA of all samples was used as reference in two-colour microarray assays. Superscript III™ Indirect labelling system (Invitrogen) and Cy3 or Cy5 fluorescent dyes (Mono-Reactive Dye Pack, Amersham Biosciences) were used to create, purify and fluorescence-label aminoallyl complementary DNA (cDNA) following the manufacturer’s (Invitrogen) instructions for indirect labelling. Cy3 (reference) and Cy5 (sample) labelled cDNA were hybridised to microarrays spotted in house with 35,852 65-mer oligonucleotide probes (mouse OpArray, 4.0, Operon, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images of hybridised slides were acquired using ScanArray® Express (Perkin Elmer Inc., USA). Acquired images were interpreted using the BlueFuse (BlueGnome) software. The arrays were first evaluated to exclude spots, which were miss-aligned or in areas with high background. Spot intensities were then calculated with Bayesian background correction filtering out those with low confidence (p < 0.05). Prior to normalisation all genes scoring less than 0.1 in their probability of biological signal in more than 25% of arrays were removed using the Genefilter Bioconductor version 2.4 package. This filter left around 50% of total genes on the array. Loess and median scale normalisation were applied to normalise data within and between arrays, respectively.

Transcriptomics statistics and bioinformatics

Statistical analyses of the filtered and normalized in vivo and in vitro microarray data were performed as described in Rasinger et al. (2014). In short, using the packages LIMMA and Multtest of the Bioconductor software suite (version 2.4, http://www.bioconductor.org) differential expression was identified and multiple test correction was applied to all p values. Genes for treatment effects were regarded as differentially expressed if the p value was below 0.05 and the multiple test corrected p value, the false discovery rate (FDR) was below 20%. Genes passing these thresholds were imported into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software suite and mapped onto their corresponding objects in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (IPA, Ingenuity Systems, USA). To compare and contrast individual and common responses to HBCD exposure in gene expression, successfully mapped genes were subjected to an IPA Core Analysis (default settings) followed by an IPA Comparison Analysis (default settings). The global Ingenuity Knowledge Base (Genes Only) was used as a reference set and included endogenous chemicals; both direct and indirect relationships were included in networks that contained at least one gene from the imported list (‘‘Focus Genes’’). Only relationships based on Experimental Observations were considered. The p values reported for over-representation of genes in functional or pathway processes are from a right-tailed Fisher’s exact test and a p value cut-off of 0.05 was applied.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

To validate the microarray assays, synthesis of cDNA was performed using 5 µg of total- RNA previously used for microarrays. cDNA was generated using Superscript III as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Primer pairs were synthesised by PrimerDesign or Qiagen (QuantiTect Primer Assay), and the sequences of primers or the Qiagen ID are shown in Supplementary Tables 1A and 1B, respectively. The assays were performed using the ABI PRISM 7700 therocycler (ABI, USA), carrying out the method as described in the SYBR Green SuperMix-UDG Kit (Invitrogen). Primer efficiency was tested and a range between 90 and 110% was considered acceptable. The housekeeping gene for qPCR normalisation was selected using GeNorm reference gene selection kit (Primerdesign), and gene Gapdh was found the least variable housekeeping gene. Quantity calculations were performed using the REST (relative expression software tool) software (Pfaffl et al. 2002). Statistical calculation of probability of differential expression were based on a randomisation of samples using the Pair Wise Fixed Reallocation Randomisation Test (Pfaffl et al. 2002). REST was set for a number of 1000 randomisations during this analysis.

Results

Cell viability and assessment of apoptosis

Cells exposed to HBCD at concentrations between 1.56 and 50 µM dose-dependent cytotoxicity compared to the control (Fig. 1a, b). Cell viability, as measured by the MTT assay, was reduced by about 20-30% at concentrations between 1.5 and 3.15 µM for N2A and NSC-19 cell lines, respectively. At concentrations greater than 6.25 µM, cell viability decreased by more than 50% for both cell lines and up to 100% at concentration of 12.5 µM for N2A cells and 25 µM for NSC-19 cell line. The EC50 was estimated to be about 5 and 6 µM for the N2A and the NSC19 cell lines, respectively (Fig. 1a, b).

Viability of N2A and NSC19 cells exposed to HBCD: a N2A and b NSC19 cells were incubated for 48 h with a geometric series of concentration between 1.56 and 50 µM of HBCD and viability was measured with the MTT assay. Three independent experiments were performed using eight replicates in each, and the average between replicates and experiments are reported (n = 3) with error bars showing the standard deviation. The regression curves were fitted in SigmaPlot (Version 12), using the “Exponential Decay, Single, 3 Parameter” model. The cellular viability is express in percentage of the DMSO control. A caspase-3 assay was used as indicator of apoptosis in the a N2A cell line and b in the NSC19 cell line exposed to HBCD. The two cell cultures were incubated for 24 h with four different concentrations of HBCD (1, 2, 4 or 8 µM). A caspase-3 fluorescence assay was then performed and the fluorescence measured every 15 min in a microplate reader with 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission, and is here expressed in arbitrary units. Three independent experiments were performed using eight replicates in each, and the average between replicates and experiments are reported (n = 3). Error bars denote standard deviation and an asterisk represents a p < 0.05

Caspase-3 activity was measured as a marker of apoptosis in cells exposed for 24 h to HBCD at concentrations ranging from 1 to 8 µM. There was a significant (p < 0.05) increase in caspase-3 enzymatic activity at 1 and 2 µM HBCD for the N2A cell line (Fig. 1c) and at 1 µM for the NSC-19 cell line (Fig. 1d). At concentrations higher than these, the caspase-3 activity showed no difference compared to the control, presumably because of the loss of viable and functional cells.

Microarray experiments

Fold-change data, associated p- and FDR-values for all statistically analysed and mapped genes are presented in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 2). In all conditions, except one (N2A, 1 µM), there were a greater number of genes that were downregulated than upregulated (Table 1). In mice exposed to HBCD through the diet (199 mg/kg bw/day) a total of 83 genes were differentially regulated, of which 10 were upregulated and 73 downregulated. The greatest number of regulated genes were observed in N2A cells treated with 2 µM HBCD. HBCD elicited distinct and overlapping responses in gene expression in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 2, Table 2). In total, 25 (30%) of the genes that were regulated in mouse brain were also regulated in either or both of the cell lines (Fig. 2). The identity and expression pattern of these are shown in Table 2. The 30% overlap between genes regulated in mouse with those regulated in the cell lines gives confidence in the analysis. The microarray results were further verified by qPCR analysis (Supplementary Table 3). Out of 15 genes found significantly regulated on microarrays, 14 were also significantly regulated when analysed by qPCR although directionality of the response was not always the same in all conditions.

Venn diagram of genes called significantly regulated (q < 0.2) in microarray analysis of mouse brain, N2A cells and NSC19 cells exposed to HBCD. Mice were exposed to HBCD via the diet for 28 days at a dose of 199 mg/kg body weight per day, resulting in a HBCD concentration in the brain of 40 µmol/kg (wet weight). N2A and NSC19 cells were exposed to either 1 or 2 µM of HBCD for 24 h and the numerals shown are the combined numbers of unique genes called significant in the two conditions. The full lists of differentially regulated genes, fold-change data and associated p- and FDR can be found in Supplementary Table 2. The Venn diagram was constructed using Venny (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html)

Pathway analysis of transcriptomics data

Significantly regulated genes (FDR < 20%) were subjected to targeted biological network analysis on the Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA®) platform (Supplementary Table 4A-D). Categories with < 3 genes were removed and non-redundant categories that were significantly enriched (p < 0.05) in brain and at least two cell culture conditions are shown in Fig. 3.

Pathway analysis of genes called significantly regulated (q < 0.2) in microarray analysis of mouse brain, N2A cells and NSC19 cells exposed to HBCD. Mice were exposed to HBCD via the diet for 28 days at a dose of 199 mg/kg body weight per day, resulting in a HBCD concentration in the brain of 40 µmol/kg (wet weight). N2A and NSC19 cells were exposed to either 1 or 2 µM of HBCD for 24 h. Lists of significantly regulated genes from each condition were subjected to pathway analysis, using the IPA software, and statistical significance of overrepresentation of genes in different “Canonical Pathways” and “Diseases & Biofunctions” are shown as a heat-map along with predicted “Upstream regulators”. Only selected pathways that had significant enrichment in mouse brain plus two cell culture conditions are shown. The full data-set including genes in each pathway is presented in Supplementary Tables 4A–D

Canonical pathways for ‘GADD45 Signaling’, ‘ATM Signaling’, ‘Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Signaling’, ‘ATM Signaling’, ‘14-3-3-mediated Signaling’ and UVA-Induced MAPK Signaling’ were significantly affected in four out of the five conditions investigated (Fig. 3). Enrichment testing of the gene-lists against ‘Diseases & Functions’ annotations revealed that HBCD caused differential expression of genes preferentially related to (1) cell proliferation, (2) cancer, (3) apoptosis, (5) cytoskeleton, and (4) neuromuscular diseases (Fig. 3).

Upstream regulator analysis in IPA® is a prediction of the transcriptional cascade based on the number of targets of “transcriptional regulators” in the dataset compared with those in the IPA® database. Broadly, the implicated upstream regulators may be divided into (1) steroid and sex hormones, (2) calcium and zinc regulation-related, (3) kinase cascades, (4) cytokine and growth-factor response, (5) neurodegenerative disease, (6) and xenobiotic response. Genes in transcriptional networks known to be regulated by ‘beta-estradiol’, ‘dihydrotestosterone’, ‘PRL’ (prolactin), ‘calcitrol’ (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol), ‘ERBB2’ (Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2; aka HER2), ‘camptothecin’, ‘CSF2’ (Colony Stimulating Factor 2), ‘trichostatin A’, ‘lipopolysaccharide’, ‘STAT3’ (Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), ‘STAT5a/b’, ‘TP73’ (Tumor Protein P73) were enriched in all five conditions, implicating these as key networks explaining the responses to HBCD (Fig. 3). The prediction of ‘l-glutamic acid’ and ‘kainic acid’ as upstream regulators is also interesting as it implicates specific effects on glutamatergic neurons.

Upon examining the prediction of upstream regulators by IPA® the large numbers of networks known to be influenced by and/or interfering with intracellular Zn2+ and Ca2+ signals was striking (Fig. 3). These also included ‘zinc’ and ‘Ca2+’ themselves. Furthermore, glutamatergic receptor activation, as implicated through ‘l-glutamic acid’ and ‘kainic acid’ as upstream regulators, results in a post-synaptic rise in intracellular [Ca2+], an effect that in many neurons is modulated my Zn2+ (Marger et al. 2014; Sensi et al. 2011; Sunuwar et al. 2017). The predominance of Zn2+ and Ca2+ regulated networks prompted us to further investigate the effects of HBCD on neuronal Zn2+ and Ca2+ signalling, focussing on glutamatergic neurons.

HBCD-evoked Zn2+ signals in N2A cells

The potential of HBCD to trigger Zn2+ signals was investigated in N2A cells using the Zn2+-specific probe, Zinpyr-1. For this experiment whole cell population fluorescence was recorded as a relative cumulative measure of intracellular [Zn2+]i and we found that exposure of cells to 1 µM HBCD caused on average a 1.2–1.4-fold increase in [Zn2+]i (p < 0.05; Fig. 4a, b). Thus, HBCD does evoke Zn2+ signals in N2A cells.

Intracellular [Zn2+] in N2A cells exposed to HBCD for 24 h. N2A cells were exposed to HBCD with or without other treatments for 24 h and intracellular Zn2+ release was detected using the Zn2+-specific fluorescent probe, Zinpyr-1. a N2A cells were incubated for 24 h with 1 µM HBCD with or without 2 h pre-incubation with the antioxidant, NAC, or the zinc chelator, DEDTC. b The N2A cell line was incubated for 24 h with 1 µM HBCD with or without 2 h pre-incubation with the NO synthase blocker, L-NAME or with DEDTC. The experiment was carried out three times with 16 technical replicates in each experiment (n = 3). Data are expressed as fold-change of fluorescence measured in the control. The bars represent the averages of values from the three experiments and error bars show the standard deviation. An asterisk and a hash sign indicate a statistical differences from untreated control cells and cells treated with 1 µM HBCD, respectively (ANOVA, p < 0.05)

Application of 1 µM of the membrane permeable zinc chelator, diethyldithiocarbamate (DEDTC) completely abolished the Zn2+ signal, confirming that fluorescence was caused by intracellular Zn2+ release (Fig. 4a, b). Zinc is released from metallothioneins and other proteins in cells by an increase in the redox potential (Berendji et al. 1997; Chung et al. 2006). Therefore, 1 µM N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) was added to the culture medium to test if the Zn2+ release was caused by HBCD-induced oxidative stress. NAC is a substrate for biosynthesis of reduced glutathione, which is the most abundant antioxidant in cells (Kerksick and Willoughby 2005). Addition of NAC partially alleviated HBCD-induced Zn2+ release compared with 1 µM HBCD alone, suggesting that oxidative stress was involved (Fig. 4a). Since nitric oxide (NO) pathway activation is a main cause of oxidative stress damage in cells, proteins and lipids (Chung 2010), we hypothesised that HBCD might activate nitric oxide synthase, leading to NO production and nitrosylation of zinc thiolate bonds in metallothioneins, leading to Zn2+ release. We, therefore, investigated the Zn2+ concentration in cells exposed to HBCD following treatment with the NO pathway blocker L-NAME. Again, HBCD triggered intracellular release of Zn2+, but contrary to our hypothesis treatment of cells with L-NAME did not reduce the HBCD evoked Zn2+ signal, indicating that the effect is not related to NOS activation (Fig. 4b). In this experiment, the release of Zn2+ following HBCD treatment alone was slightly but not significantly lower than that shown in Fig. 4a, however, the reversal of this signal by DEDTC was more substantial than in the experiment described in Fig. 4a and 1.4-fold below the Zinpyr-1 fluorescence in control cells. Such quantitative differences between experiments can be caused by variability in Zinpyr-1 and/or DEDTC loading. Importantly, the significant increase of intracellular Zn2+ by HBCD and the reversal of this signal by DEDTC were maintained in both set of experiments. Thus, it can be concluded that HBCD causes intracellular Zn2+ release through oxidative stress, but this is not a result of nitric oxide synthase activation.

HBCD inhibition of metabotropic Ca2+ signals in primary neuronal cultures

Many glutamatergic neurons co-release glutamate and Zn2+ (Sensi et al. 2011; Sunuwar et al. 2017; Marger et al. 2014). To determine the effect of HBCD treatment on signalling capacity of cells in primary neuronal cultures, we wanted to determine the glutamate and extracellular Zn2+ dependent Ca2+ responses triggered via metabotropic receptors (Besser et al. 2009; Ganay et al. 2015; Kato et al. 2012). We initially asked what is the concentration of HBCD that is toxic to primary neurons. Hippocampal neuronal cultures were treated with HBCD at 1, 2, or 4 µM of HBCD for 24 h and control neurons were treated with the solvent (DMSO). We then fluorescently monitored the Ca2+ responses in Fura-2 loaded cells by single cell recording. In control cells, application glutamate (200 µM) triggered a rapid rise of Fura-2 fluorescence (about 60–70% increase above baseline fluorescence; Fig. 5a, b), as previously described for these metabotropic intracellular Ca2+ responses (Besser et al. 2009; Ganay et al. 2015). The perfusing extracellular solution was Ca2+-free, thus allowing measurements of the initial metabotropic response triggered to release Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum stores. Following HBCD treatment, cultures were stained with DAPI and as shown in the inserts Fig. 5b, cell survival was slightly reduced, however, Fura-2 analysis is performed only on the surviving neurons, which are able to induce esterase-dependent cleavage of the AM group. Hence although some of the cells did not survive, we were able to perform the analysis even on cultures treated with 2 µM of HBCD. Interestingly, treatment of the cultures with 1 µM of HBCD caused an approximately 50% decrease in the glutamate-dependent Ca2+ signalling in viable neurons, but no further reduction was observed at higher concentrations (Fig. 5a, b). We then asked if the role of Zn2+ and Ca2+ highlighted by the network analysis may represent a change in the response of the ZnR/GPR39, a metabotropic pathway that senses changes in extracellular Zn2+ to trigger Ca2+ signalling (Besser et al. 2009; Ganay et al. 2015). We, therefore, applied Zn2+ as was previously shown to activate the ZnR/GPR39 (Chorin et al. 2011; Saadi et al. 2012). Indeed, as shown in the inserts of Fig. 5c, an intracellular Zn2+ sensitive dye, Fluozin-3, did not exhibit a change of signal in hippocampal neurons following administration of Zn2+ (200 µM) under the same conditions used to trigger ZnR/GPR39 signalling (dashed top-left panel). In the control hippocampal cells (Fig. 5c) Zn2+ (200 µM) triggered a rapid rise of Fura-2 fluorescence (about 60–70% increase above baseline fluorescence), similar to the response to glutamate (Fig. 5a). In contrast, following emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores, using Thapsigargin (200 nM) and ATP (5 µM), we did not detect an increase in the signal of the Ca2+ sensitive dye Fura-2 (Fig. 5c, top-right insert). Thus, we conclude that the application of Zn2+, at concentrations and times used here, induces metabotropic signalling in hippocampal neurons as we have shown previously (Ganay et al. 2015; Saadi et al. 2012). We then studied the effect of HBCD on the extracellular Zn2+ dependent Ca2+ signalling. The Zn2+-dependent Ca2+ response in cells treated with HBCD was abolished resulting in about 90% inhibition of the signal by all concentrations of HBCD tested (Fig. 5c, d). The lower initial rates of the response to both glutamate and Zn2+ suggest that metabotropic signalling is impaired by the HBCD treatment. This may result from partial depletion of the intracellular Ca2+ stores as well as changes in the functional properties or expression of the metabotropic receptors. Hence, while HBCD treatment yielded a small, albeit clear, metabotropic response to glutamate, the response to Zn2+ was largely absent in the treated cells.

HBCD effects on glutamate- and zinc-dependent Ca2+ transients. Primary hippocampal mixed neuronal cultures were exposed to 1 or 2 µM of HBCD for 24 h. Cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM and intracellular Ca2+ responses to (a, b) glutamate (200 µM, 30 s) or (c, d) Zn2+ (200 µM, 30 s) were monitored. A representative Ca2+ response (a, c) and the averaged initial rates of fluorescence change (b, d) are shown. Note that the Ca2+ response is monitored after a short lag time following the application of the ligand, likely due to the timing of the perfusion system. The initial rate of the response is dependent on the net influx of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm and represents the activity of GPR39. Inserts to b show representative DAPI staining of neuronal cultures, seeded with the same number of cells, following control (DMSO alone) or HBCD treatment at the indicated concentration. Inserts to c show: left panel: neurons loaded with the Zn2+ sensitive dye, Fluozin-3 AM, treated with Zn2+ (200 µM, 30 s) as marked by the bar; right panel: Neurons loaded with Fura-2 AM, treated with Thapsigargin (200 nM) and ATP (5 µM) as marked, and subsequent to the depletion of Ca2+ stores and recovery of the fluorescent signal to baseline, Zn2+ (200 µM, 30 s) was applied as marked. The bars represent the arithmetic mean of three independent experiments, each consisting of at least 7 averaged replicates for each condition (n = 3), **p < 0.01

Discussion

Omics technologies enable experiments that can implicate molecular networks affected by toxicants and shed light on key events in adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) (EFSA 2014). Because omics profiling can be carried out without prior hypothesis, they can be considered unbiased and discovery-driven. In the present study, we sought to characterise robust transcriptomic responses to HBCD by combining gene expression profiles resulting from in vivo and in vitro exposures. We compared gene expression profiles in brain of juvenile mouse orally exposed for 28 days to HBCD to those in two neuronally derived cell lines exposed to HBCD for 1 day, and were able to implicate a number of gene networks that were affected both in vivo and in vitro. These gene sets included networks previously identified as being targeted by HBCD (hypothalamus-pituitary–gonadal axis; Ca2+ signalling), but interestingly also shed light on several new pathways that were affected. Some of the more notable of these were pathways involved in DNA repair and cell proliferation, and transcriptional networks activated by zinc signals, tyrosine kinase receptors, inflammation, and reactive oxygen species.

A few previous studies have focussed on transcript and protein profiling in the liver of rodents and zebrafish treated with HBCD, and these collectively provide very strong evidence for interference with basic metabolic pathways (gluconeogenesis/glycolysis, amino acid/protein metabolism, lipid metabolism) and stress responses (Canton et al. 2008; Kling and Forlin 2009; Miller et al. 2016). However, cultured human cell lines from lung (A549) and liver (HepG2/C3A) showed few changes in global transcript and metabolite profiles in response to HBCD concentrations up to 2 µM (Zhang et al. 2015). Oral exposure of female Balb/c mice to HBCD with the same exposure regime and conditions as in the present study was previously found by our team to result in differential expression of 90 genes and 10 proteins (Rasinger et al. 2014). The list of differentially expressed genes in our previous study was particularly enriched for olfactory receptors, G-coupled proteins, and protein tyrosine phosphatases (Rasinger et al. 2014). In the present study, the number of differentially regulated genes in mouse brain following HBCD exposure (83 genes) was very similar to that in our earlier experiment (90 genes). Many of the genes found to be regulated in our previous study were also differentially expressed in mouse brain and neuronal cell lines in the present study.

IPA analysis revealed a strong inference of neuronal dyshomeostasis of Ca2+ and Zn2+ and implication of glutamatergic neurons being affected. We carried on with mechanistic studies in cultured cells to show that HBCD does indeed disrupt both Ca2+ and Zn2+ signalling in neurons. Effects of HBCD on calcium homeostasis have been described before in cell lines of neuronal and cardiac origin (Al-Mousa and Michelangeli 2014; Dingemans et al. 2009; Wu et al. 2016b) and are now corroborated by in vivo evidence, based on transcriptional networks in mouse brain, and targeted experimental information on reduced Ca2+ transients in response to glutamate in isolated hippocampal neurons. The demonstration of HBCD disruption of neuronal Zn2+ homeostasis is completely novel, although this mechanism of action has been proposed for triclosan effects on rat thymocytes (Tamura et al. 2012) and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin effects on brain (Rasinger et al. 2014). Disruption of cellular Zn2+ homeostasis is also recognised as a mechanism of action for soft Lewis acid transition element, such as cadmium and mercury (Kawanai et al. 2009; Predki and Sarkar 1994).

Our understanding of and appreciation for the roles of zinc in biology and disease of the brain has been hugely increased in recent years (Marger et al. 2014; McCord and Aizenman 2014; Sensi et al. 2011; Tamano et al. 2016). Deficiency or excess of Zn2+ can cause alteration in behaviour, abnormal central nervous system development, and neurological disease (Bitanihirwe and Cunningham 2009). In the brain, Zn2+ modulates neuronal post-synaptic potentials and synaptic plasticity, and is implicated in the processes of learning and memory (Marger et al. 2014; Tamano et al. 2016). The vast majority of zinc in cells including neurons is bound to metalloproteins, but ionic Zn2+ is concentrated in synaptic vesicles of a sub-set of glutamatergic neurons (also known as zincergic neurons) (Sensi et al. 2011). Synaptic Zn2+ is co-released with glutamate and acts as neuromodulator of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Anderson et al. 2015; Pan et al. 2011; Qian and Noebels 2005; Sensi et al. 2011; Takeda 2000) or AMPA receptors (Kalappa et al. 2015). The GluN2A subunit of the NMDA receptor has a high affinity Zn2+-binding site that mediates allosteric inhibition of post-synaptic currents (Sensi et al. 2011). There is also evidence for a physiological role of Zn2+ inhibition of γ-amino butyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) transmission via blockage of T-type Ca2+ channels (Grauert et al. 2014). Finally, Zn2+ can evoke post-synaptic currents via activation of GPR39, which is a metabotropic zinc receptor that stimulates Ca2+ release in cells (Besser et al. 2009) and regulates neuronal excitability (Chorin et al. 2011; Gilad et al. 2015; Saadi et al. 2012). In the present study, we show that HBCD depresses glutamate and zinc evoked Ca2+ transients in hippocampal neurons that survived the HBCD treatment and were able to hydrolyse the Fura-2 AM to allow the measurement. Inactivation of SERCA by HBCD has been demonstrated, and this may lead to some depletion of the cytosolic Ca2+ stores. However, we show that the inhibitory effect is stronger in Zn2+ treated cells compared to the glutamate treatment, suggesting that there is also a direct effect on the metabotropic signalling pathway and not only on the Ca2+ stores.

HBCD also stimulates intracellular Zn2+ release in N2A cells. The ability of NAC to partially alleviate the HBCD-evoked Zn2+ signal confirms that low levels of HBCD can generate oxidative stress (Deng et al. 2009). However, this effect was not caused by NOS activation as L-NAME did not influence Zn2+ release. In light of the physiological roles of synaptic Zn2+ in neural transmission and specific functions in mediating synaptic plasticity for learning and memory or cell death, disruption in neuronal zinc homeostasis could be causing adverse apical effects. For example, exposure to 1 µM HBCD activated caspase-3 activity in N2A and NSC19 cells (Fig. 1c, d) and microarray analysis revealed that apoptotic gene networks were affected in brain of HBCD exposed mice as well as in both neuronal cell lines (Fig. 3). Moreover, Zn2+ and Ca2+ cooperate in mediating neuronal apoptosis in response to ischemia, oxidative stress, and other forms of injury (McCord and Aizenman 2013, 2014). This interaction converges on the voltage-gated, delayed rectifier K+ channel Kv2.1, which when activated and residing in the plasma membrane allows the efflux of K+ required for apoptosis (McCord and Aizenman 2013, 2014). Kv2.1 is activated through phosphorylation by p38 MAPK and tyrosine kinase Src. Both these kinases are activated by intracellular Zn2+ signals (Hogstrand et al. 2009; McCord and Aizenman 2013), and p38 MAPK was a predicted upstream regulator in HBCD exposed mouse brain, N2A cells and NSC19 cells in the present study. Translocation of Kv2.1 from endosomes to the plasma membrane where it is active is mediated by syntaxin SNARE proteins downstream CaMK2 activation (McCord and Aizenman 2013). Interestingly, we found in our previous study that CaMK2 expression is regulated in mouse brain during HBCD exposure (Rasinger et al. 2014) and in the present study the CaMK2 inhibitory protein, CaMKN2, was a predicted upstream regulator of gene expression. Furthermore, the transcript for its paralogue, CaMKN1, was significantly regulated in both cell lines following exposure to 2 µM HBCD (Supplementary Table 2). We, therefore, hypothesise that apoptosis in brain of HBCD exposed mice was triggered by the disruption of Ca2+ and Zn2+ homeostasis.

Prediction of upstream regulators following HBCD exposure implicated gene networks in the hypothalamus-hypophysis-gonadal axis (GnRH1, 17ß-oestradiol, dihydrotestosterone) as well as prolactin (PRL) with regulation by 17ß-oestradiol and dihydrotestosterone being statistically significant in mouse brain, both cell lines, and both doses (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 4B). This finding is in line with earlier findings that HBCD has endocrine disruption potential (Hamers et al. 2006; Krivoshiev et al. 2016; Maranghi et al. 2013; van der Ven et al. 2009). Developmental exposure of Wistar rats to HBCD resulted in reduced testicular size with a lower confidence limit for a 5% effect of as little as 11.5 mg/kg body weight per day (van der Ven et al. 2009). Our team has previously observed an increased serum testosterone concentration and testosterone/17ß-oestradiol ratio in female Balb/c mice undergoing the same HBCD exposure regime as that used in the present study [199 mg/kg body weight per day for 28 days; (Maranghi et al. 2013)]. In the present study, HBCD effects on oestrogen and androgen gene networks were observed not only in vivo but also on two different neuronal cell lines, strongly suggesting direct effects on sex steroid target tissue. HBCD showed both anti-androgenic and anti-oestrogenic activity in CALUX® sex-steroid receptor reporter gene assays and anti-oestrogenic activity in a MCF-7 cell proliferation assay (Hamers et al. 2006; Krivoshiev et al. 2016). This suggests that HBCD may bind to and disable sex-steroid nuclear receptors and would be consistent with animal data from the present and previous studies (Maranghi et al. 2013; van der Ven et al. 2009).

References

Alm H et al (2008) Exposure to brominated flame retardant PBDE-99 affects cytoskeletal protein expression in the neonatal mouse cerebral cortex. Neurotoxicology 29:628–637. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2008.04.021

Al-Mousa F, Michelangeli F (2014) The sarcoplasmic–endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is the likely molecular target for the acute toxicity of the brominated flame retardant hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD). Chem Biol Interact 207:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2013.10.021

American Chemistry Council (2001) Draft Screening Assessment of Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD). http://www.ec.gc.ca/lcpe-cepa/default.asp?lang=En&n=A27E7A60-1&offset=13&toc=show (consulted on May 2011)

Anderson CT, Radford RJ, Zastrow ML, Zhang DY, Apfel UP, Lippard SJ, Tzounopoulos T (2015) Modulation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors by synaptic and tonic zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E2705–E2714. doi:10.1073/pnas.1503348112

Berendji D, Kolb-Bachofen V, Meyer KL, Grapenthin O, Weber H, Wahn V, Kröncke K-D (1997) Nitric oxide mediates intracytoplasmic and intranuclear zinc release. FEBS Lett 405:37–41. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00150-6

Berntssen MHG, Julshamn K, Lundebye A-K (2010) Chemical contaminants in aquafeeds and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) following the use of traditional-versus alternative feed ingredients. Chemosphere 78:637–646. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.021

Besser L, Chorin E, Sekler I, Silverman WF, Atkin S, Russell JT, Hershfinkel M (2009) Synaptically released zinc triggers metabotropic signaling via a zinc-sensing receptor in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 29:2890–2901. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5093-08.2009

Birnbaum LS, Staskal DF (2004) Brominated flame retardants: cause for concern? Environ Health Perspect 112:9–17. doi:10.1289/ehp.6559

Bitanihirwe BKY, Cunningham MG (2009) Zinc: the Brain’s dark horse. Synapse 63:1029–1049. doi:10.1002/syn.20683

Canton RF, Peijnenburg A, Hoogenboom R, Piersma AH, van der Ven LTM, van den Berg M, Heneweer M (2008) Subacute effects of hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) on hepatic gene expression profiles in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 231:267–272. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.013

Chain EPoCitF (2012) Scientific opinion on emerging and novel brominated flame retardants (BFRs) in food. EFSA J 10:2908. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2908

Chorin E et al (2011) Upregulation of KCC2 Activity by Zinc-Mediated Neurotransmission via the mZnR/GPR39 Receptor. J Neurosci 31:12916–12926. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2205-11.2011

Chung KKK (2010) Modulation of pro-survival proteins by S-nitrosylation: implications for neurodegeneration. Apoptosis 15:1364–1370

Chung MJ, Hogstrand C, Lee SJ (2006) Cytotoxicity of nitric oxide is alleviated by zinc-mediated expression of antioxidant genes. Exp Biol Med 231:1555–1563

Covaci A et al (2006) Hexabromocyclododecanes (HBCDs) in the environment and humans: a review. Environ Sci Technol 40:3679–3688

Curran CP, Vorhees CV, Williams MT, Genter MB, Miller ML, Nebert DW (2011) In utero and lactational exposure to a complex mixture of polychlorinated biphenyls: toxicity in pups dependent on the Cyp1a2 and Ahr genotypes. Toxicol Sci 119:189–208. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq314

de Wit CA, Herzke D, Vorkamp K (2010) Brominated flame retardants in the Arctic environment—trends and new candidates. Sci Total Environ 408:2885–2918. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.08.037

de Wit CA, Björklund JA, Thuresson K (2012) Tri-decabrominated diphenyl ethers and hexabromocyclododecane in indoor air and dust from Stockholm microenvironments 2: indoor sources and human exposure. Environ Int 39:141–147. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.11.001

DeLegge MH, Smoke A (2008) Neurodegeneration and inflammation. Nutr Clin Pract 23:35–41

Deng J et al (2009) Hexabromocyclododecane-induced developmental toxicity and apoptosis in zebrafish embryos. Aquat Toxicol 93:29–36. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.03.001

Dingemans MML, Heusinkveld HJ, de Groot A, Bergman A, van den Berg M, Westerink RHS (2009) Hexabromocyclododecane inhibits depolarization-induced increase in intracellular calcium levels and neurotransmitter release in PC12 cells. Toxicol Sci 107:490–497. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn249

Drage DS, Newton S, de Wit CA, Harrad S (2016) Concentrations of legacy and emerging flame retardants in air and soil on a transect in the UK West Midlands. Chemosphere 148:195–203. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.01.034

EFSA (2014) Modern methodologies and tools for human hazard assessment of chemicals. EFSA J 12:3638. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3638

Eljarrat E, Guerra P, Martínez E, Farré M, Alvarez JG, López-Teijón M, Barceló D (2009) Hexabromocyclododecane in human breast milk: levels and enantiomeric patterns. Environ Sci Technol 43:1940–1946. doi:10.1021/es802919e

Eriksson P, Fischer C, Wallin M, Jakobsson E, Fredriksson A (2006) Impaired behaviour, learning and memory, in adult mice neonatally exposed to hexabromocyclododecane (HBCDD). Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 21:317–322

Fängström B, Athanassiadis I, Odsjö T, Norén K, Bergman Å (2008) Temporal trends of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and hexabromocyclododecane in milk from Stockholm mothers, 1980–2004. Mol Nutr Food Res 52:187–193. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700182

Fromme H, Becher G, Hilger B, Voelkel W (2016) Brominated flame retardants—exposure and risk assessment for the general population. Int J Hyg Environ Health 219:1–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.08.004

Ganay T, Asraf H, Aizenman E, Bogdanovic M, Sekler I, Hershfinkel M (2015) Regulation of neuronal pH by the metabotropic Zn2+-sensing Gq-coupled receptor, mZnR/GPR39. J Neurochem 135:897–907. doi:10.1111/jnc.13367

Genskow KR, Bradner JM, Hossain MM, Richardson JR, Caudle WM (2015) Selective damage to dopaminergic transporters following exposure to the brominated flame retardant. HBCDD Neurotoxicol Teratol 52:162–169. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2015.06.003

Gilad D, Shorer S, Ketzef M, Friedman A, Sekler I, Aizenman E, Hershfinkel M (2015) Homeostatic regulation of KCC2 activity by the zinc receptor mZnR/GPR39 during seizures. Neurobiology Disease 81:4–13. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.020

Grauert A, Engel D, Ruiz AJ (2014) Endogenous zinc depresses GABAergic transmission via T-type Ca2+ channels and broadens the time window for integration of glutamatergic inputs in dentate granule cells. J Physiol Lond 592:67–86. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261420

Hamers T et al (2006) In vitro profiling of the endocrine-disrupting potency of brominated flame retardants. Toxicol Sci 92:157–173. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj187

Hogstrand C, Kille P, Nicholson RI, Taylor KM (2009) Zinc transporters and cancer: a potential role for ZIP7 as a hub for tyrosine kinase activation. Trends Mol Med 15:101–111

Ibhazehiebo K, Iwasaki T, Xu M, Shimokawa N, Koibuchi N (2011) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) ameliorates the suppression of thyroid hormone-induced granule cell neurite extension by hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD). Neurosci Lett 493:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.062

Kalappa BI, Anderson CT, Goldberg JM, Lippard SJ, Tzounopoulos T (2015) AMPA receptor inhibition by synaptically released zinc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:15749–15754. doi:10.1073/pnas.1512296112

Kato HK, Kassai H, Watabe AM, Aiba A, Manabe T (2012) Functional coupling of the metabotropic glutamate receptor, InsP3 receptor and L-type Ca2+ channel in mouse CA1 pyramidal cells. J Physiol 590:3019–3034. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2012.232942

Kawanai T, Satoh M, Murao K, Oyama Y (2009) Methylmercury elicits intracellular Zn2+ release in rat thymocytes: its relation to methylmercury-induced decrease in cellular thiol content. Toxicol Lett 191:231–235. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.09.003

Kerksick C, Willoughby D (2005) The antioxidant role of glutathione and N-acetyl-cysteine supplements and exercise-induced oxidative stress. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2:38–44. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-2-2-38

Kling P, Forlin L (2009) Proteomic studies in zebrafish liver cells exposed to the brominated flame retardants HBCD and TBBPA. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 72:1985–1993. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2009.04.018

Krivoshiev BV, Dardenne F, Covaci A, Blust R, Husson SJ (2016) Assessing in vitro estrogenic effects of currently-used flame retardants. Toxicol In Vitro 33:153–162. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2016.03.006

Law RJ et al (2005) Hexabromocyclododecane challenges scientists and regulators. Environ Sci Technol 39:281A–287A

Lilienthal H, van der Ven LTM, Piersma AH, Vos JG (2009) Effects of the brominated flame retardant hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) on dopamine-dependent behavior and brainstem auditory evoked potentials in a one-generation reproduction study in Wistar rats. Toxicol Lett 185:63–72. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.002

Maranghi F et al (2013) Dietary exposure of juvenile female mice to polyhalogenated seafood contaminants (HBCD, BDE-47, PCB-153, TCDD): comparative assessment of effects in potential target tissues. Food Chem Toxicol 56:443–449. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.056

Marger L, Schubert CR, Bertrand D (2014) Zinc: an underappreciated modulatory factor of brain function. Biochem Pharmacol 91:426–435. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.08.002

Mariussen E, Fonnum F (2003) The effect of brominated flame retardants on neurotransmitter uptake into rat brain synaptosomes and vesicles. Neurochem Int 43:533–542. doi:10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00044-5

McCord MC, Aizenman E (2013) Convergent Ca2+ and Zn2+ signaling regulates apoptotic Kv2.1K + currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110:13988–13993. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306238110

McCord MC, Aizenman E (2014) The role of intracellular zinc release in aging, oxidative stress, and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00077

Miller I et al (2016) Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) induced changes in the liver proteome of eu- and hypothyroid female rats. Toxicol Lett 245:40–51. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.01.002

Pan E et al (2011) Vesicular zinc promotes presynaptic and inhibits postsynaptic long-term potentiation of mossy fiber-CA3 synapse. Neuron 71:1116–1126. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.019

Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L (2002) Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e36

Predki PF, Sarkar B (1994) Metal Replacement in zinc-finger and its effect on DNA-binding. Environ Health Perspect 102:195–198

Qian J, Noebels JL (2005) Visualization of transmitter release with zinc fluorescence detection at the mouse hippocampal mossy fibre synapse. J Physiol Lond 566:747–758

Rasinger JD, Carroll TS, Lundebye AK, Hogstrand C (2014) Cross-omics gene and protein expression profiling in juvenile female mice highlights disruption of calcium and zinc signalling in the brain following dietary exposure to CB-153, BDE-47, HBCD or TCDD. Toxicology 321:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2014.03.006

Rawn DFK, Gaertner DW, Weber D, Curran IHA, Cooke GM, Goodyer CG (2014a) Hexabromocyclododecane concentrations in Canadian human fetal liver and placental tissues. Sci Total Environ 468:622–629. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.014

Rawn DFK et al (2014b) Brominated flame retardant concentrations in sera from the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) from 2007 to 2009. Environ Int 63:26–34. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2013.10.012

Roosens L, Abdallah MAE, Harrad S, Neels H, Covaci A (2009) Exposure to hexabromocyclododecanes (HBCDs) via dust ingestion, but not diet, correlates with concentrations in human serum: preliminary results. Environ Health Perspect 117:1707–1712. doi:10.1289/ehp.0900869

Ryan JJ, Rawn DFK (2014) The brominated flame retardants, PBDEs and HBCD, in Canadian human milk samples collected from 1992 to 2005; concentrations and trends. Environ Int 70:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.04.020

Saadi RA, He K, Hartnett KA, Kandler K, Hershfinkel M, Aizenman E (2012) Snare-dependent upregulation of potassium chloride co-transporter 2 activity after metabotropic zinc receptor activation in rat cortical neurons in vitro. Neuroscience 210:38–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.001

Schreder ED, La Guardia MJ (2014) Flame retardant transfers from US households (Dust and Laundry Wastewater) to the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Technol 48:11575–11583. doi:10.1021/es502227h

Sensi SL, Paoletti P, Koh J-Y, Aizenman E, Bush AI, Hershfinkel M (2011) The Neurophysiology and Pathology of Brain Zinc. J Neurosci 31:16076–16085. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3454-11.2011

Shi Z et al (2013) Levels of tetrabromobisphenol A, hexabromocyclododecanes and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in human milk from the general population in Beijing. China Sci Total Environ 452:10–18. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.038

Sunuwar L, Gilad D, Hershfinkel M (2017) The zinc sensing receptor, ZnR/GPR39, in health and disease. Frontiers Biosci Landmark 22:1469–1492. doi:10.2741/4554

Takeda A (2000) Movement of zinc and its functional significance in the brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 34:137–148

Tamano H, Koike Y, Nakada H, Shakushi Y, Takeda A (2016) Significance of synaptic Zn2+ signaling in zincergic and non-zincergic synapses in the hippocampus in cognition. J Trace Elem Med Biol 38:93–98. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2016.03.003

Tamura I, Kanbara Y, Saito M, Horimoto K, Satoh M, Yamamoto H, Oyama Y (2012) Triclosan, an antibacterial agent, increases intracellular Zn2+ concentration in rat thymocytes: Its relation to oxidative stress. Chemosphere 86:70–75. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.09.009

van der Ven LTM et al (2006) A 28-day oral dose toxicity study enhanced to detect endocrine effects of hexabromocyclododecane in wistar rats. Toxicol Sci 94:281–292. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfl113

van der Ven LTM et al (2009) Endocrine effects of hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) in a one-generation reproduction study in Wistar rats. Toxicol Lett 185:51–62. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.003

Viberg H, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P (2003) Neonatal PBDE 99 exposure causes dose-response related behavioural derangements that are not sex or strain specific in mice. Toxicol Sci 72:126

Vorkamp K, Bester K, Rigét FF (2012) Species-specific time trends and enantiomer fractions of hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) in biota from East Greenland. Environ Sci Technol 46:10549–10555. doi:10.1021/es301564z

Wu M-H et al (2016a) Occurrence of Hexabromocyclododecane in soil and road dust from mixed-land-use areas of Shanghai, China, and its implications for human exposure. Sci Total Environ 559:282–290. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.166

Wu M, Wu D, Wang C, Guo Z, Li B, Zuo Z (2016b) Hexabromocyclododecane exposure induces cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmia by inhibiting miR-1 expression via up-regulation of the homeobox gene Nkx2.5. J Hazard Mater 302:304–313. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.10.004

Xia M et al (2008) Compound cytotoxicity profiling using quantitative high-throughput screening. Environ Health Perspect 116:284–291. doi:10.1289/ehp.10727

Zhang J, Williams TD, Abdallah MA-E, Harrad S, Chipman JK, Viant MR (2015) Transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches to investigate the molecular responses of human cell lines exposed to the flame retardant hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD). Toxicol In Vitro 29:2116–2123. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2015.08.017

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by Aquamax (EU-contract no. 016249-2), a Project funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (www.aquamaxip.eu) and the Project “Seafood and mental health: Uptake and effects of marine nutrients and contaminants alone or in combination on neurological function” (Grant No. 186908/I30) a Project funded by the Research Council of Norway. The author(s) would like to acknowledge networking support by the COST Action TD1304 (Zinc-Net). Gene expression analyses were carried out at The Genomics Centre, King’s College London. Drs Mathew Arno and Estibaliz Aldecoa-Otalora Astarloa are acknowledged for their excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VR, JDR, TSC and GT conducted the experiments. AKL was in charge of design and production of the diets. CH, AKL and MH were the principal investigators and supervised the project. CH drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to discussion of the results and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Reffatto, V., Rasinger, J.D., Carroll, T.S. et al. Parallel in vivo and in vitro transcriptomics analysis reveals calcium and zinc signalling in the brain as sensitive targets of HBCD neurotoxicity. Arch Toxicol 92, 1189–1203 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-017-2119-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-017-2119-2