Abstract

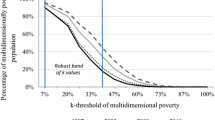

Multidimensional poverty comparisons can be sensitive to the choice of weights assigned to the indicators as well as the aggregate poverty measure used. This paper examines the robustness of trends in multidimensional poverty in the Philippines to these choices by presenting estimates for three alternative weighting schemes and three methods of identification and aggregation. Using data for 2004–2013, the paper finds evidence of a significant decline in multidimensional poverty that is robust to these alternatives, though the magnitude of the decline in and the dimensional contributions to aggregate multidimensional poverty are quite sensitive to the alternatives considered.

Source: Based on official poverty estimates from the National Statistics Coordination Board, and national accounts statistics from the Philippines Statistics Authority

Source: Official poverty estimates from the National Statistics Coordination Board, the Philippines Statistics Authority; APIS survey data sets for rounds 2004 through 2013

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Sen’s writings on this subject are many; referenced here are only a few examples (including one of the early ones).

Even from the welfarist perspective of consumption expenditure as a money metric of utility, consumption may be inadequate as there are other arguments in individual utility functions for which markets (and hence prices) may not exist or, if they exist, may be distorted.

Even in the absence of market failures, total consumption or income as a linear combination of prices and quantities of goods and services implies perfect substitutability between these goods and services—an assumption that is questionable from a non-welfarist or human rights perspective that insists on the essentiality of minimum levels of achievement across a range of dimensions.

These official estimates are based on per capita incomes from the first-semester Family Income and Expenditure Surveys (FIES) for 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2012, and the Annual Poverty Indicators Surveys (APIS) for 2013 and 2014. The APIS surveys are only conducted for the first semester of the survey year. Since 2013, the APIS has used the same income module as the FIES.

Note that the standard errors for full-year official poverty incidence (percentage of population below the poverty line) for 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2015 were 0.49, 0.52, 0.54 and 0.76, respectively, while those for the first semester incidence were 0.39, 0.46, 0.56 and 0.55, respectively (PSA 2016a and tables accessed online from https://psa.gov.ph/tags/official-poverty-statistics).

Balisacan (2015) in fact presents estimates for a longer period for some of his data sources. In particular, the study uses FIES data for the years 1998, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009 and 2012; NDHS for 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008; and APIS data for 1998, 2002, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2010 and 2011.

Most of the literature has concentrated on the identification and aggregation issues with the choice of dimensions and weights having remained relatively under-explored.

For related work, see Alkire et al. (2017) who present an analysis of changes in multidimensional poverty over time for 34 countries following the global MPI approach. Their detailed analysis at both national and sub-national levels, however, does not explore robustness to methodological choices in measuring multidimensional poverty.

The survey is considered representative at the national and regional levels, but not at the provincial level. For further information on the APIS survey design and instruments, see Philippines Statistics Authority (2014).

The indicator list was developed in consultation with the staff from the Philippines Statistics Authority.

See Appendix in the online supplementary material for details of how the official food poverty line is determined. Alternatively, nutritional deprivation could be defined as falling below the food poverty line itself, but the more stringent criterion is used here to focus on those facing significant shortfalls in food consumption.

Information on illness/injury over the reference period is collected for all household members. APIS survey documentation indicates that the respondent is “an adult knowledgeable member of the sample family who can provide accurate answers to all or most of the questions in the survey.”

There are many examples. For instance, for Colombia’s MPI, two of the 15 indicators relate to the absence of long-term unemployment and formal employment, and these indicators are included under “Labour” as a separate dimension. For South Africa, “Economic Activity” is included as a separate dimension, with an indicator on unemployment among 15–64-year-old adults. The Ecuador MPI has “Work and Social Security” as a separate dimension, with an indicator on unemployment or inadequate employment among those 18 years or older. Similarly, for Costa Rica, “Work” is included as a separate dimension, with indicators on long-duration unemployment, informal employment and earnings less than the minimum wage. Employment dimension or indicators are also included in MPIs for El Salvador and Chile.

See Decanq and Lugo (2013) for a review.

This is arbitrary but yields a subjective poverty incidence of about 22% that is not very different to the official income poverty incidence of 25% (for 2003 based on FIES).

The estimation of marginal effects takes into account the fact that the independent variables in the regression are also dichotomous.

See Datt (2018) for a formal statement of this property as well as further discussion of why the union approach may be worth considering.

For the present analysis based on this select set of indicators, survey non-response is not an issue. Based on the available documentation, unit non-response is low at about 4% or less across different APIS rounds. Item non-response for the variables we are interested is virtually zero in the data set.

Note that Balisacan (2015) does not use exactly the same indicators as in this paper. The table reports his weights for the APIS application, lining them up as closely as possible against the indicators in this paper.

Using the 10 indicators, however, the decline in multidimensional poverty over 2004–2011 is of similar magnitude across the three weighting schemes. But this also omits the last year 2013 due to the comparability issue with the illness/injury-related indicator.

Also see Roche (2013) and Alkire et al. (2017) for related application of Shapley decomposition, though applied to changes in multidimensional poverty over two points in time. Dimensional decomposition by comparison has an added degree of complexity as it involves a large number of decomposition factors determined by all possible paths of elimination of deprivations in individual dimensions.

Note that the contribution of food consumption is still higher than its weight, which reflects a larger fraction of the population deprived in terms of food consumption relative to other indicators.

References

Alkire S, Foster JE (2011) Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J Public Econ 95(7–8):476–487

Alkire S, Foster JE (2016) Dimensional and distributional contributions to multidimensional poverty Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. OPHI Working Paper 100, University of Oxford

Alkire S, Santos ME (2014) Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Dev 59:251–274

Alkire S, Foster JE, Seth S, Santos ME, Roche JM, Ballon P (2015) Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Alkire S, Roche JM, Vaz A (2017) Changes over time in multidimensional poverty: methodology and results for 34 countries. World Dev 94:232–249

Balisacan AM (2015) The growth-poverty nexus: multidimensional poverty in the philippines. In: Balisacan AM, Chakravorty U, Ravago M-LV (eds) Sustainable economic development: resources, environment, and institutions, Chapter 24. Academic Press, Oxford

Bellani L (2013) Multidimensional indices of deprivation: the introduction of reference groups weights. J Econ Inequal 11:495–515

Bellani L, Hunter G, Anand P (2013) Multidimensional welfare: do groups vary in their priorities and behaviours? Fisc Stud 34:333–354

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2011) International happiness: a new view on the measure of performance. Acad Manag Perspect 25:6–22

Cerioli A, Zani S (1990) A fuzzy approach to measurement of poverty. In: Dagum C, Zenga M (eds) Income and wealth distribution, inequality and poverty. Springer, Berlin, pp 272–284

Chakravarty SR, D’Ambrosio C (2006) The measurement of social exclusion. Review of Income and Wealth 523:377–398

Datt G (2018) Distribution-sensitive multidimensional poverty measures. World Bank Economic Review (forthcoming)

Decancq K, Van Ootegem L, Verhofstadt E (2013) What if we voted on the weights of a multidimensional well-being index? An illustration with flemish data. Fisc Stud 34:315–332

Decanq K, Lugo MA (2013) Weights in multidimensional indices of wellbeing: an overview. Econom Rev 32:7–34

Desai M, Shah A (1988) An econometric approach to the measurement of poverty. Oxford Economic Papers 40:505–522

Dooley D, Catalano R, Wilson G (1994) Depression and unemployment: panel findings from the epidemiologic catchment area study. Am J Community Psychol 61(3):745–765

Dooley D, Prause J, Ham-Rowbottom K (2000) Inadequate employment and high depressive symptoms: panel analyses. Int J Psychol 35:294

Helliwell J, Putnam R (2004) The social context of well-being. Philos Trans R Soc B 359:1435–1446

ILO (International Labour Organization) (2010) Emerging risks and new patterns of prevention in a changing world of work. ILO, Geneva

Lundin A, Hemmingsson T (2009) Unemployment and suicide. Lancet 374:270–271

Mitra S, Jones K, Vick B, Brown D, McGinn E, Alexander MJ (2013) Implementing a multidimensional poverty measure using mixed methods and a participatory framework. Soc Indic Res 110:1061–1081

Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) (2014) 2013 annual poverty indicators survey: final report. Philippines Statistics Authority, Manila

Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) (2016a) 2015 full year official poverty statistics of the Philippines. Philippines Statistics Authority, Quezon City

Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) (2016b) 2015 first semester official poverty statistics of the Philippines. Philippines Statistics Authority, Quezon City

Roche JM (2013) Monitoring progress in child poverty reduction: methodological insights and illustration to the case study of Bangladesh. Soc Indic Res 2013(112):363–390

Sen A (1980) Equality of what? (lecture delivered at Stanford University, 22 May 1979). In: MacMurrin SM (ed) The tanner lectures on human values, vol 1. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City

Sen A (1985) Commodities and capabilities. North-Holland, New York

Sen A (1999) Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, New York

Shorrocks AF (2013) Decomposition procedures for distributional analysis: a unified framework based on the Shapley value. J Econ Inequal 11(1):99–126

Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A (2009a) The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet 374:315–323

Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A (2009b) The health implications of financial crisis: a review of the evidence. Ulster Med J 78(3):142–145

Stutzer A, Lalive R (2004) The role of social work norms in job searching and subjective well-being. J Eur Econ Assoc 2(4):696–719

UNDP (2014) Human development report 2014: sustaining human progress: reducing vulnerability and building resilience. Macmillan, New York

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author would like to thank Regina Salve Baroma, Carolina Diaz-Bonilla, Nandini Krishnan, Xubei Luo, Paul Mariano, Sharon Faye Piza, and Mara Warwick for useful comments or other forms of help. Comments from the journal reviewer were also very helpful in improving the paper. The paper, however, represents the views of the author alone.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Datt, G. Multidimensional poverty in the Philippines, 2004–2013: How much do choices for weighting, identification and aggregation matter?. Empir Econ 57, 1103–1128 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1493-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1493-9