Abstract

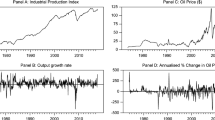

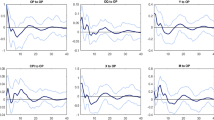

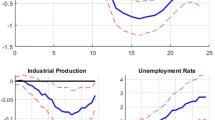

This paper provides an empirical evidence on the influence of oil price uncertainty on the real economic activity in Jordan and Turkey during the period 1986:01–2014:12. To measure the effect of uncertainty, the paper combines a bivariate structural VAR with a GARCH-in-mean process that allows oil volatility to affect the growth of industrial production. Our results indicate that oil market uncertainty has a negative influence on the industrial output of Jordan and Turkey. For instance, the increase in one standard error of oil price uncertainty is found to be associated with a decline of 0.81 and 1.01% in the industrial production of Jordan and Turkey, respectively. Moreover, consistent with the recent empirical evidence, we find that output growth increases/decreases after a negative/positive oil price shock. These results imply that sound energy policies that mitigate the effect of oil market uncertainty may help in stabilizing output in both countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The theoretical foundations of the theories of investment under uncertainty and real options at the firm level are developed by Henry (1974), Bernanke (1983), Brennan and Schwartz (1985), Majd and Pindyck (1987), Brennan (1990), Gibson and Schwartz (1990), Triantis and Hodder (1990), and Aguerrevere (2009).

It is expected for economic activity in large countries to influence the oil market. Therefore, oil is endogenous and this should be reflected by the model that studies output–oil relationship.

Our analysis is restricted only to these two countries because sufficient data on industrial production index are unavailable for most of MENA countries.

Turkey is more sensitive to oil price uncertainty shocks compared to Jordan because of its higher oil intensity in terms of the amount of oil consumption needed to produce a unit of its GDP.

If oil volatility has a negative effect, then the impulse response of output is asymmetric. This point has been raised to us thankfully by one of the referees.

The theoretical literature, however, does not provide any definitive guideline for choosing appropriate level of lag length in a VAR model. However, Hamilton and Herrera (1983, 1996, 2004), Hooker (1996), and Jiménez-Rodríguez and Sánchez (2005) argue that a lag length of 4 quarter (12 months) is sufficient to capture the dynamic impacts of oil price shocks on real activity. Consequently, we use the long lag of 12 as is common with prior empirical literature (i.e., Herrera et al. 2011, 2015; Kilian and Vigfusson 2011a, b), although our results are robust to alternatives lag length.

Based on the Schwartz Information Criterion, we choose a lag length of \(q=r=1\) in Eq. (2).

The sample is selected on the basis of the availability of data of the industrial production index.

In some previous literature, the scale of economic output is measured by real gross domestic production (GDP) on quarterly basis (see, i.e., Rahman and Serletis 2012; Kilian and Vigfusson 2014). However, time series for quarterly GDP data is only available from 1999 and 2003 for Jordan and Turkey, respectively. Therefore, in this paper we use the industrial production index to proxy real GDP.

Very similar results were obtained when using Texas Intermediate crude oil as a benchmark for oil prices.

Over our sample period, we find that the correlation coefficient between WTI and Brent oil prices is 0.9864.

Very similar results were obtained when denominating the oil price in the country-specific consumer price index, which was obtained from the IFS. We also got similar results when the nominal price of oil was used.

We estimated conditional volatility of real oil price using AR(1)–GARCH(1,1) model.

We also test the lag length using the AIC, FPE, and HQC information criteria. All suggest that 12 lags are sufficient to summarize the dynamics of the system.

For a robustness check, we re-estimated the model for a sample that excludes the recent global financial crises. Results have not changed. Still the influence of uncertainty is negative and highly significant. The coefficients with the t-statistics were \(-\) 0.03 (\(-\) 3.44) and \(-\) 0.03 (\(-\) 3.69) for Jordan and Turkey, respectively.

Oil intensity is measured as the oil consumption needed to produce one unit of GDP. Energy diversification is defined as diversification of energy sources. Following the empirical literature (e.g., Löschel et al. 2010), we use the Herfindahl–Hirschman (HH) index to measure diversification energy sources. This index is equal to the sum of the squares of the fractional share of each source (standardized in energy units). The more energy diversification of energy sources, the lower is the value of the index. We use six energy sources in calculating the HH index: crude oil, natural gas, coal, hydropower, nuclear power, and other forms of renewable energy (geothermal, solar, wind, wood, and waste electricity generation). The data on share in total energy consumption of each energy source were retrieved from the US Energy Information Administration (http://www.eia.gov/opendata/).

Note that energy diversification is more helpful in mitigating the negative influence on output when prices and price volatilities of different energy sources are weakly correlated.

The budget deficit due to the oil subsidy scheme has been always covered by foreign aid from Saudi Arabia and other oil-rich Arab countries.

Currently, Jordan is adopting the pegged exchange rate regime. The Jordanian Dinar is pegged to the US dollar. Turkey is adopting a floating exchange rate regime.

Note that similar results are obtained when we use 6- and 24-month forecast horizon. These results are only available from the authors upon request.

Herrera et al. (2015) also argue that the standard lag selection criteria such as the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) do not work well for nonlinear models and may yield misleading results in small samples.

That is, we restrict the coefficient on oil price uncertainty to zero, which effectively eliminates the multivariate GARCH-in-mean term from Eq. (6).

Note that getting the fitted volatilities from the structural VAR with multivariate GARCH also produce similar results.

Note that given the weak dependence of structural breaks, we expect tiny values in the off-diagonal locations of the volatility matrices of the BEKK and hence similar results. A drawback of this model is that it complicates the interpretation of the structural shocks. This point has been raised to us thankfully by one of the referees.

References

Aguerrevere FL (2009) Real options, product market competition, and asset returns. J Finance 64:957–983

Ahmad H, Bashar O, Wadud I (2012) The transitory and permanent volatility of oil prices: what implications are there for the US industrial production? Appl Energy 92:447–455

Alquist R, Kilian L, Vigfusson R (2011) Forecasting the price of oil. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1911194 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1911194

Atkeson A, Patrick JK (1999) Models of energy use: putty-putty versus putty-clay. Am Econ Rev 89:1028–1043

Aye G, Dadam V, Gupta R, Mamba B (2014) Oil price uncertainty and manufacturing production. Energy Econ 43:41–47

Baumeister C, Peersman G (2013) Time-varying effects of oil supply shocks on the US economy. Am Econ J Macroecon 5:1–28

Bernanke B (1983) Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. Q J Econ 98:85–106

Bernanke BS, Gertler M, Watson M (1997) Systematic monetary policy and the effects of oil price shocks. Brookings Papers Econ Act 1:91–157

Bohi DR (1991) On the macroeconomic effects of energy price shocks. Resour Energy 13:145–162

Bredin D, Elder J, Fountas S (2011) Oil volatility and the option value of waiting: an analysis of the G-7. J Futures Mark 31:679–702

Brennan MJ (1990) Latent assets. J Finance 45:709–730

Brennan MJ, Schwartz ES (1985) Evaluating natural resource investments. J Bus 58:135–157

Brown SP, Yücel MK (2002) Energy prices and aggregate economic activity: an interpretative survey. Q Rev Econ Finance 42:193–208

Dixit AK, Pindyck RS (1994) Investment under uncertainty. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Donayre L, Wilmot NA (2015) The asymmetric effects of oil price shocks on the Canadian economy. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2567576 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2567576

Edelstein P, Kilian L (2007) The response of business fixed investment to changes in energy prices: a test of some hypotheses about the transmission of energy price shocks. BE J Macroecon 7:35

Edelstein P, Kilian L (2009) How sensitive are consumer expenditures to retail energy prices? J Monet Econ 56:766–779

Elder J (2003) An impulse-response function for a vector autoregression with multivariate GARCH-in-mean. Econ Lett 79:21–26

Elder J (2004) Another perspective on the effects of inflation uncertainty. J Money Credit Bank 36:911–28

Elder J, Serletis A (2009) Oil price uncertainty in Canada. Energy Econ 31:852–856

Elder J, Serletis A (2010) Oil price uncertainty. J Money Credit Bank 42:1137–1159

Elder J, Serletis A (2011) Volatility in oil prices and manufacturing activity: an investigation of real options. Macroecon Dyn 15:379–395

Engle RF, Kroner KF (1995) Multivariate simultaneous generalized ARCH. J Econ Theory 11:122–150

Ferderer JP (1997) Oil price volatility and the macroeconomy. J Macroecon 18:1–26

Gibson R, Schwartz ES (1990) Stochastic convenience yield and the pricing of oil contingent claims. J Finance 45:959–976

Gisser M, Goodwin TH (1986) Crude oil and the macroeconomy: tests of some popular notions: Note. J Money Credit Bank 18:95–103

Hamilton JD (1983) Oil and the macroeconomy since World War II. J Polit Econ 91:228–48

Hamilton JD (1988) A neoclassical model of unemployment and the business cycle. J Polit Econ 96:593–617

Hamilton JD (1996) This is what happened to the oil price-macroeconomy relationship. J Monet Econ 38:215–220

Hamilton JD (2003) What is an oil shock? J Econom 113:363–98

Hamilton JD (2013) Historical oil shocks. In: Parker RE, Whaples R (eds) Routledge Handbook of major events in economic history. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, New York, pp 239–265

Hamilton JD, Herrera AM (2004) Oil shocks and aggregate macroeconomic behavior: The role of monetary policy: comment. J Money Credit Bank 36:265–86

Henry C (1974) Investment decisions under uncertainty: the irreversibility effect. Am Econ Rev 64:1006–1012

Herrera AM, Lagalo LG, Wada T (2011) Oil price shocks and industrial production: is the relationship linear? Macroecon Dyn 15:472–497

Herrera AM, Lagalo LG, Wada T (2015) Asymmetries in the response of economic activity to oil price increases and decreases? J Int Money Finance 50:108–133

Hooker MA (1996) What happened to the oil price-macroeconomy relationship? J Monet Econ 38:195–213

Jiménez-Rodríguez R, Sánchez M (2005) Oil price shocks and real GDP growth: empirical evidence for some OECD countries. Appl Econ 37:201–228

Jo S (2014) The effects of oil price uncertainty on global real economic activity. J Money Credit Bank 46:1113–1135

Kilian L (2009) Not all oil price shocks are alike: disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market. Am Econ Rev 99:1053–1069

Kilian L (2014) Oil price shocks: causes and consequences. Annu Rev Resour Econ 6:133–154

Kilian L, Vega C (2011) Do energy prices respond to US macroeconomic news? A test of the hypothesis of predetermined energy prices. Rev Econ Stat 93:660–671

Kilian L, Vigfusson RJ (2011a) Nonlinearities in the oil price-output relationship. Macroecon Dyn 15:337–363

Kilian L, Vigfusson RJ (2011b) Are the responses of the US economy asymmetric in energy price increases and decreases? Quant Econ 2:419–453

Kilian L, Vigfusson RJ (2014) The role of oil price shocks in causing U.S. recessions. International Finance Discussion Papers No. 1114, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2014/1114/ifdp1114.pdf

Kroner FK, Ng VK (1998) Modelling asymmetric comovements of asset returns. Rev Financ Stud 11:817–844

Lee K, Ni S (2002) On the dynamic effects of oil price shocks: a study using industry level data. J Monet Econ 49:823–852

Lee K, Ni S, Ratti RA (1995) Oil shocks and the macroeconomy: the role of price variability. Energy J 16:39–56

Löschel A, Moslener U, Rübbelke DTG (2010) Indicators of energy security in industrialised countries. Energy Policy 38:1665–1671

Majd S, Pindyck RS (1987) Time to build, option value, and investment decisions. J Financ Econ 18:7–27

Mehrara M (2008) The asymmetric relationship between oil revenues and economic activities: the case of oil-exporting countries. Energy Policy 36:1164–1168

Mork KA (1989) Oil and the macroeconomy when prices go up and down: an extension of Hamilton’s results. J Political Econ 97:740–4

Mork KA (1994) Business cycles and the oil market. Energy J 15:15–38

Mory JF (1993) Oil prices and economic activity: is the relationship symmetric? Energy J 14:151–161

Pindyck RS (1991) Irreversibility, uncertainty, and investment. J Econ Lit 29:1110–48

Plante M, Traum N (2011) Time-varying oil price volatility and macroeconomic aggregates: what does theory say? In: Midwest Economics Association Conference. http://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/114889/N_Traum.pdf

Rahman S, Serletis A (2011) The asymmetric effects of oil price shocks. Macroecon Dyn 15:437–471

Rahman S, Serletis A (2012) Oil price uncertainty and the Canadian economy: evidence from a VARMA, GARCH-in-mean, asymmetric BEKK mode. Energy Econ 34:603–610

Serletis A, Istiak K (2013) Is the oil price-output relation asymmetric? J Econ Asymmetries 10:10–20

Triantis AJ, Hodder JE (1990) Valuing flexibility as a complex option. J Finance 45:549–565

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees of Empirical Economics for their valuable and helpful comments. The authors are responsible for any remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maghyereh, A.I., Awartani, B. & Sweidan, O.D. Oil price uncertainty and real output growth: new evidence from selected oil-importing countries in the Middle East. Empir Econ 56, 1601–1621 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1402-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1402-7