Abstract

We examine the impact of the Allowance for Newborn Children, a universal baby bonus offered by the Canadian province of Quebec, on birth order, sibship sex composition, income, and education. We find a large response for third- and higher-order births for which the bonus was more generous. Interestingly, though, we find stronger response if there were two previous sons or a previous son and daughter rather than two previous daughters. We also find, in addition to a transitory effect, a permanent effect, with the greatest increase in one daughter-two son families among three-child households. Moreover, we find a hump shape response by income group, with the greatest response from middle-income families. Also, women with at least some post-secondary education respond more to the policy than those with less. These findings suggest that properly structured pro-natal policies can successfully increase fertility among different segments of the population while simultaneously diminishing the effect of gender preferences and fertility disparity related to women’s education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unfortunately, the cancelation of the policy is announced well in advance and replaced by universal childcare; this creates a less credible experimental environment at the end of the policy period.

New theoretical models are accounting for observed heterogeneous effects. For example, to account for the effect of a child-care policy on fertility, Yakita (2018) allows for responses to differ by level of maternal education.

Milligan (2005) estimates a probit regression with the variable “family income.” He finds an overall positive coefficient, whereas we subgroup family income and estimate the same model to find the marginal effects of each income subgroup. Here, we are able to find a hump shape response for family income.

The baby bonus was paid to all births that were registered; we find no evidence of differences in ANC take-up rates by income.

We confirm this calculation.

In simulation, if applicable, we assume that the second child is 6 years old and the third child is 10 years old.

In 1997, after our sample period, Ontario introduced a means-tested child care supplement for working parents (Milligan and Stabile 2011).

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 106-9013.

With the confidential data, we are able to look at annual TFR for each year of age, whereas past papers using the public-use data have had to use 5-year age intervals.

From all the Canadian provinces, the province of Ontario is the most comparable to Quebec; they are neighbors, as well as the two most populated provinces in Canada. There are many cities and towns on the border of these two provinces, and in one instance, they even share the same metropolitan area (Ottawa-Gatineau).

See Hotz et al. (1997) for a detailed comparison on total fertility rates (TFR) and completed fertility rates (CFR).

In addition to graphical findings, we estimate a difference-in-differences (DID) model using the TFR as the outcome of interest for Quebec and Ontario with 1995 as the treatment year and 1988 as the comparison year. The DID model results in a 0.11 increase in the number of children born to Quebecois women in the treated year. As Manski and Pepper (2018) point out, such DID estimates require strong assumption on DID invariance. Following Manski and Pepper, we apply a class of the bounded-variation assumptions. We use the data prior to 1988 to calculate the bound parameter of bounded time variation, bounded inter-province variation, and bounded DID variation. The bounded DID estimates are between 0.104 and 0.199. These models are available upon request.

We also compared Quebec to the Rest of Canada and find that it closely mirrors that of Ontario illustrating that the gaps we are observing in Quebec are not just in comparison to Ontario.

Although the universal childcare policy is announced to start at the same time the baby bonus is canceled, no new subsidized childcare spaces were created before 2001 (Haeck et al. 2015). In Norway, Havnes and Mogstad (2011) find that formal childcare acts as a substitute for informal childcare (arrangements with relatives, friends, and so forth) instead of encouraging new female labor force participation. Baker et al. (2008) examine childcare use in Quebec and do find some crowding out of existing arrangements is evident.

Milligan (2002) writes that the rate for third and subsequent births in Quebec increased by 35%, from 0.217 per woman in 1987 to 0.294 in 1993, while falling elsewhere in Canada by 3%.

We also show a transitory effect took place both graphically and in regression analysis. Our graphical results can be seen in the Appendix, Fig. 6. The figure shows the birth cumulative distribution function for each of three cohorts by age of mother and parity, separately for Ontario and Quebec. The difference between Ontario and Quebec is most evident for the third child, where one can observe the “middle cohort” in Quebec having children much earlier than their Ontario counterparts.

The main shortcoming of Milligan’s (2005) study of the ANC is that the public-use census does not provide year of birth. This meant that the ANC policy period overlaps the 1991 census window, making it difficult to disentangle which births are part of the policy period. Also, the public-use census file has a very small sample size and does not allow for a thorough examination of heterogeneous effects like the confidential census file.

As a robustness check we also use a 3-year and 5-year window. See Section 6.2 for more detail.

We limit the sample to women aged 34 to ensure we can identify all children; there is a concern that if the woman is older than 34 years of age she may have children living outside the home.

As a robustness check, we examine the effect of the baby bonus on all single women. See Section 6.2 for more detail.

Another reason we only look at married women is because we do not want to model the relationship between the decision to be married and fertility as studied in Baudin et al. (2015).

We use the Canadian Consumer Price Index (CPI) for each province to convert nominal income into real income in 1992 constant Canadian dollars.

A household is located in an urban dwelling if it is located in a census metropolitan area (CMA), which is one or more municipalities with at least 100,000 people.

In some instances, we also utilized a triple-difference model; however, we prefer the ease of interpretation provided by subsampling the difference-in-differences model. The triple-difference results match well with our preferred model. Results of the triple-difference are available upon request.

Special care is taken into calculating average partial effects instead of partial effects evaluated at the mean. We observe individual’s characteristics to calculate an individual probability and then average all those probabilities, as opposed to mean marginal effects, where the mean for each variable is plugged in to calculate a probability. We calculate the marginal probability using the method described in Ai and Norton (2003).

The approach of using “probability of having a child” as the dependent variable is not new to this literature (see Cohen et al. 2013).

The definition of immigrant in this case comes from the Census definition, which represents all individuals not born as a Canadian citizen.

Nitsche et al. (2018) find evidence that it is important to also account for the male partner’s education level as it also significantly predicts fertility.

We also estimated n = 4 or more children and find that the results are similar to those for n = 3 or more.

We limit our sample to women aged 35 to 39 because they are near the end of childbearing, while still being young enough to have their children living at home. The census only accounts for the number of children present in the household; thus, if we include older women, we may be missing children that are no longer living at home.

This calculation is based on the average marginal effect for the interaction term divided by the proportion of women that had a child in Quebec in our pre-policy period (1987–88), which was 0.207.

The representative female used to calculate the probability of having a child is a married non-immigrant francophone woman who is 30–34 years old, with some post-secondary education, lives in an urban area, and has no previous children. These characteristics are chosen as they are the most common female we encounter in our sample and thus make the most general comparison.

Since younger women are likely to return to school, as a robustness check, we estimate our specification considering only women over 25 years of age and results do not change significantly.

Households’ response to having two children is negative since they are likely moving to a family with three children given the large cash incentive.

The sample size drops to 90,000 households. Also, Quebec has almost four times the number of observations than Ontario. Thus, this is not our preferred specification. The CMAs we selected are Temiskming Shores, North Bay, Petawawa, Pembroke, Hawkesbury, Cornwall, Rouyn-Noranda, Lachute, Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Val-d’Or, and Amos.

We drop 12 strata because they contain less than 5 observations for each province and each period.

Results available upon request.

References

Ai C, Norton EC (2003) Interaction term in logit and probit models. Econ Lett 80:123–129

Almond D, Edlund L, Milligan K (2013) Son preference and the persistence of culture: evidence from south and east Asian immigrants to Canada. Popul Dev Rev 39(1):75–95

Andersson G, Hank K, Ronsen M, Vikat A (2006) Gendering family composition: sex preferences for children and childbearing behavior in the Nordic countries. Demography 43(2):255–267

Ang XL (2015) The effects of cash transfer fertility incentives and parental leave benefits on fertility and labor supply: evidence from two natural experiments. J Fam Econ Iss 36(2):263–288

Angrist JD, Evans WN (1998) Children and their parents’ labor supply: evidence from exogenous variation in family size. Am Econ Rev 88(3):450–477

Angrist JD, Lavy V, Schlosser A (2010) Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ 28(4):773–824

Baker M, Gruber J, Milligan K (2008) Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. J Polit Econ 116(4):709–745

Battle K, Mendelson M (1997) Child benefit reform in Canada: an evaluative framework and future directions. Caledon Institute of Social Policy

Baudin T, de la Croix D, Gobbi PE (2015) Fertility and childlessness in the United States. Am Econ Rev 105(6):1852–1882

Baughman R, Dickert-Conlin S (2009) The earned income tax credit and fertility. J Popul Econ 22(3):537–563

Becker GS (1960) An economic analysis of fertility. In: Bureau U-N (ed) Demographic and economic change in developed countries: a conference of the Universities-National Bureau Committee for Economic Research, vol 11. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 209–231

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Becker GS, Lewis G (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2):S279–S288

Becker GS, Tomes N (1976) Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 84(4):S143–S162

Bernard A (1989) Government Policies. L’Année Politique au Québec 1987–1988. Denis Monière, ed. Montréal, Le Devoir, Québec-Amérique

Berrington A (2004) Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behavior. Popul Trends 117:9–19

Bjorklund A (2006) Does family policy affect fertility? J Popul Econ 19:3–24

Bongaarts J (2001) Fertility and reproductive preferences in post-transitional societies. Popul Dev Rev 27:260–281

Brewer M, Ratcliffe A, Smith S (2012) Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. J Popul Econ 25:245–266

Cigno A (1986) Fertility and the tax-benefit system: a reconsideration of the theory of family taxation. Econ J 96:1035–1051

Cigno A, Ermish J (1989) A microeconomic analysis of the timing of births. Eur Econ Rev 33:737–760

Cohen A, Dehejia R, Romanov D (2013) Do financial incentives affect fertility? Rev Econ Stat 95(1):1–20

Cygan-Rehm K (2016) Parental leave benefit and differential fertility responses: evidence from a German reform. J Popul Econ 29:73–103

Dahl GB, Moretti E (2008) The demand for sons. Rev Econ Stud 75(4):1085–1120

Duclos E, Lefebvre P, Merrigan P (2001) A natural experiment on the economics of storks: evidence on the impact of differential family policy on fertility rates in Canada. Working Paper No. 136, CREFE

Esping-Andersen G (2009) The incomplete revolution. Adapting to women’s new roles. Polity Press, Cambridge

Freedman D, Freedman R, Whelpton PK (1960) Size of family and preference for children of each sex. Am J Sociol 66(2):141–146

Gonzalez L (2013) The effect of a universal child benefit on conceptions, abortions, and early maternal labor supply. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(3):160–188

Haeck C, Lefebvre P, Merrigan P (2015) Canadian evidence on ten years of universal preschool policies: the good and the bad. Labour Econ 36:137–157

Havnes T, Mogstad M (2011) Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. J Public Econ 95:1455–1465

Heckman JJ, Walker JR (1990) The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: evidence from Swedish longitudinal data. Econometrica 58(6):1411–1441

Heiland F, Prskawetz A, Sanderson WC (2008) Are individuals’ desired family size stable? Evidence from West German panel data. Eur J Popul 24(2):129–156

Hotz VJ, Miller R (1988) An empirical analysis of life cycle fertility and female labor supply. Econometrica 56(1):91–118

Hotz VJ, Klerman JA, Willis RJ (1997) The econometrics of fertility in developed countries. In: Rosenzweig MR, Stark O (eds) Handbook of population economics. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam

Hoynes H (1995) Does welfare play any role in female headship decisions? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 5149

Jones L, Tertilt M (2008) An economic history of fertility in the U.S.: 1826–1960. In: Rupert P (ed) Frontiers of family economics. Emerald Press, London, pp 165–230

Kim YA (2012) Impact of direct cash transfer on fertility by income and education subgroup: study of allowance for newborn children of Canada. Korean J Popul Stud 35:29–55

Kim YA (2014) Lifetime impact of cash transfer on fertility. Can Stud Popul 41:97–110

Kravdal O, Rindfuss RR (2008) Changing relationships between education and fertility: a study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. Am Sociol Rev 73:854–873

La Presse (1988) Baisse d'impots pour tous. May 13, p. A-1

Lalive R, Zweimuller J (2009) How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. Q J Econ 124(3):1363–1402

LaLumia S, Sallee JM, Turner S (2015) New evidence on taxes and the timing of birth. Am Econ J Econ Pol 7(2):258–293

Laroque G, Salanie B (2008) Does fertility respond to financial incentives? CESifo working paper 2339

Manski CF, Pepper JV (2018) How do right-to-carry laws affect crime rates? Coping with ambiguity using bounded-variation assumptions. Rev Econ Stat 100(2):232–244

Milligan K (2002) Quebec’s baby bonus: can public policy raise fertility? Backgrounder, C.D. Howe Institute,1–9

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Milligan K (2016a) Canadian tax and credit simulator. Database, software and documentation, Version 2016-2

Milligan K (2016b) Finances of the nation. Can Tax J 64(3):601–618

Milligan K, Stabile M (2011) Do child tax benefits affect the well-being of children? Evidence from Canadian child benefit expansions. Am Econ J Econ Pol 3(3):175–205

Moffitt R (1994) Welfare effects on female headship with area effects. J Hum Resour 29(2):621–636

Mogstad M, Wiswall M (2016) Testing the quantity-quality model of fertility. Quant Econ 7:157–192

Montreal Gazette (1988a) Have more babies, liberals say. February 28, p. A-1

Montreal Gazette (1988b) Parizeau’s family plan: triple baby bonus. March 15, p. A-1

Neyer G, Andersson G (2008) Consequences of family policies on childbearing behavior: effects or artifacts? Popul Dev Rev 34(4):699–724

Nitsche N, Matysiak A, Van Bravel J, Vignoli D (2018) Partners’ educational pairings and fertility across Europe. Demography 55:1195–1232

Ost B, Dziadula E (2016) Gender preference and age at arrival among Asian immigrant mothers in the US. Econ Lett 145:286–290

Palermo T, Handa S, Peterman A, Prencipe L, Seidenfeld D (2016) Unconditional government social cash transfer in Africa does not increase fertility. J Popul Econ 29:1083–1111

Parent D, Wang L (2007) Tax incentives and fertility in Canada: quantum vs tempo effects. Can J Econ 40(2):371–400

Pop-Eleches C (2006) The impact of an abortion ban on socioeconomic outcomes of children: evidence from Romania. J Polit Econ 114(4):744–773

Quesnel-Vallee A, Morgan SP (2003) Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the US. Popul Res Policy Rev 22(5–6):497–525

Raute A (2017) Can financial incentives reduce the baby gap? Evidence from a reform in maternity leave benefits. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 23793. Forthcoming: Journal of Public Economics

Riphahn RT, Wiynck FJ (2017) Fertility effects of child benefits. J Popul Econ 30:1135–1184

R v Morgentaler (1988) 1 SCR 30, 37 CCC (3d)

Shang Q, Weinberg BA (2013) Opting for families: recent trends in the fertility of highly educated women. J Popul Econ 26:5–32

Testa MR (2014) On the positive correlation between education and fertility intentions in Europe: individual-and country-level evidence. Adv Life Course Res 21:28–42

Williamson N (1983) Parental sex preferences and sex selection. In: Bennett N (ed) Sex selection of children. Academic Press, New York, NY

Yakita A (2018) Fertility and education decisions and child-care policy effects in a Nash-bargaining family model. J Popul Econ 31:1177–1201

Young M (1998) Immigration: The Canada-Quebec Accord. Publication BP-252E, Parliamentary Research Branch, Library of Parliament, Ottawa

Zhang J, Quan J, Van Meerbergen P (1994) The effect of tax-transfer policies on fertility in Canada, 1921-1988. J Hum Resour 29:181–201

Acknowledgements

We thank Byron Spencer for his guidance and support. We would also like to thank Philip DeCicca, Arthur Sweetman, Laura Turner, participants at the Canadian Population Society Annual Conference, the European Society for Population Economics Annual Conference, the Canadian Economic Association Annual Conference, the Annual Congress of the European Economic Association, and the University of New Brunswick for their helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank the anonymous referees and the editor, Alessandro Cigno, for their detailed and insightful comments. We would also like to thank Peter Kitchen from Statistics Canada for all his help. The analysis presented in this paper was conducted at the Research Data Centre at McMaster which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). The services and activities provided by the Research Data Centre at McMaster are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of the SSHRC, the CIHR, the CFI, Statistics Canada, and McMaster University. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the CRDCN’s or that of its partners’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Natalie Malak has received grants from Ontario Graduate Scholarships for her doctoral degree. Md Mahbubur Rahman and Terry A. Yip have received support from the Ontario Student Assistance Program for their doctoral degrees.

Conflict of interest

Beyond these, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Fig. 4

Total family benefit for household income of $20,000. The first vertical bar signifies the start of the ANC policy in May 1988, and the second vertical bar signifies the end of the policy in September 1997. Source: Milligan (2016a), Canadian Tax and Credit Simulator. Database, software, and documentation, version 2016-2

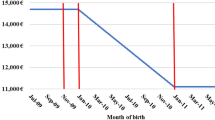

Fig. 5

Total family benefit for household income of $60,000. The first vertical bar signifies the start of the ANC policy in May 1988, and the second vertical bar signifies the end of the policy in September 1997. Source: Milligan (2016a), Canadian Tax and Credit Simulator. Database, software, and documentation, version 2016-2

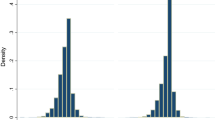

Fig. 6

Birth cumulative distribution function by mother’s age, cohorts aged 15–39. Birth Vital Statistics source. The “old cohort” was born between 1959 and 1962 and aged 26–38 during the policy; the “middle cohort” was born between 1963 and 1968 and aged 20–34 during the policy; and the “young cohort” was born between 1969 and 1972 and aged 16–28 during the policy

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malak, N., Rahman, M.M. & Yip, T.A. Baby bonus, anyone? Examining heterogeneous responses to a pro-natalist policy. J Popul Econ 32, 1205–1246 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00731-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00731-y