Abstract

We exploit the 1996 reform of the German child benefit program to identify the causal effect of heterogeneous child benefits on fertility. While generally the reform increased child benefits, the exact amount of the increase varied by household income and the number of children. We use these heterogeneities to identify their causal effects on fertility in a difference-in-difference setting. We apply the large samples of the German Mikrozensus and the rich data of the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). The reform effects on low-income couples are not statistically significant. We find some support for positive fertility effects for higher as opposed to lower income couples deciding on a second birth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Brewer et al. (2012) study the same reform and find that the fertility of women in couples indeed increased after the reform.

Tamm (2010) studies the same reform with a focus on female labor market participation. Similar to González (2013), he finds that the increase in benefits caused a decline in maternal hours of work. In an earlier contribution using time series methods and data for the period 1960–1995, Cigno et al. (2003) find positive effects of a broadly defined child benefit on the annual total fertility rate in a VAR model.

This argument strictly holds for higher order fertility, only. For first births, an increase in benefits does not generate an unconditional income effect because the transfer is conditional on having a child.

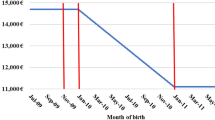

Families with an annual income below 11,232 DM saved nothing, because they did not pay any income taxes. Families with an annual income above 244,188 DM paid the maximum tax rate of 53% and thus saved 4104 DM × 0.53 / 12 = 181 DM per month and child.

The benefits rose even further in 1997 and again in 1999. By 1999, they had reached 250 DM for the first and second, 300 and 350 for the third and fourth child, respectively.

It was not the family but the tax authority, which automatically chose the financially more attractive option for each individual family. Generally, gross family annual income for couples with one child had to surpass about 146,500 DM after the reform to make the tax exempt amounts more attractive (about 153,000 DM for couples with two children). Based on our data, fewer than 5% of couple and family households were in this top income bracket. Therefore, the vast majority of families benefited from child benefits rather than the tax credit.

As tax and child benefit laws differentiate between married and unmarried couples, the patterns for unmarried couples are slightly different.

Net transfers dropped by between 9.50 DM and 18.85 DM per year, i.e., negligible amounts.

For a similar argument see, e.g., the discussion of child benefit effects in Cigno (1986, p. 1042).

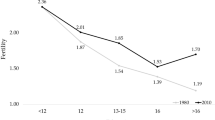

Cohen et al. (2013) find smaller responses to a given child benefit increase among high than among low-income households.

If children are in training, parents can receive benefits up until age 25.

In principle, welfare recipients constitute an independent control group for the reform. However, as our data provide very few births in this subsample (56 overall), we only pursue this strategy as a robustness check.

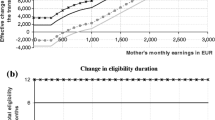

In Appendix Fig. 15, we show the reform induced shift in marginal and average tax rates.

For second births, this is under a caveat. The difference in the benefit change between high and low incomes must be sufficient to outweigh the higher shadow price of children for high-income couples. As discussed in Sect. 2, empirical analysis must show whether this is the case.

However, the Bundestag first discussed the reform in March 1995 and its specifics were under debate until October. If (potential) parents adjusted their fertility choices already in anticipation and conceived a child as early as April 1995, births as early as January 1996 may already be in response to the reform. This is an unlikely outcome: first, it is uncommon that pregnancies occur immediately, and, second, it would be surprising to see parents respond already to the possibility of a reform. However, in the unlikely event that parents responded to the reform very early, we were to underestimate the true reform effect because we would overestimate pre-reform fertility.

Exact data are available in the SOEP, as well. However, the small number of observations in the relevant groups does not permit informative depictions of the developments; the resulting figures jump erratically.

We do not study the behavior of single women because their fertility rates are very low (1.25% among childless and 1.0% among those with one child compared to about 10% among couples) and because their economic situation of single mothers is governed by different mechanisms: it is affected by the scarcity of childcare supply for infants in the 1990s and social norms that pushed recent mothers out of the labor market. About one third of single mothers receive welfare benefits. We expect that single mothers respond less to child benefit reforms than couples. The issue is left for further research.

The Mikrozensus provides the age of all members of the surveyed households. If there is a child of age 0 living in the household, we consider this to be a recent birth.

In a robustness test, we consider fathers’ education only, in order to avoid the potential endogeneity of maternal education with respect to fertility choices. Table 13 in the Appendix describes the ISCED coding in terms of school and vocational degrees. We present the distribution of annual household net income and the income-specific birth rates in Figs. 16 and 17 in the Appendix.

This threshold lies at annual gross household incomes of roughly 63,000 DM. Since we only have data on net income in the Mikrozensus, we provide the income distribution in terms of net income, for which the threshold is roughly at 43,000 DM.

We use the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), data for years 1984–2013, version 30, SOEP, 2014, doi:10.5684/soep.v30.

In the Mikrozensus data, we dropped non-nationals because there is no information on the preferable indicator of migration background.

When dividing the estimate of the reform effect (0.037) by the pre-reform birth rate for highly educated couples in the narrow definition (0.164), 22.6% are obtained, see Table 2.

When dividing the estimate of the reform effect (0.013) by the pre-reform birth rate for highly educated couples in the broad definition (0.135), 9.6% are obtained, see Table 2.

In further estimations, we considered net household incomes reduced by the female’s earnings. When considering only male incomes, which are arguably more exogenous, we find significant negative treatment effects for low-income households regarding first births and significant positive effects for high-income households regarding second births (see Table 21). We obtain the same results when we consider imputed incomes. In addition, we replaced the education proxies that are based on both spouses’ education outcomes by focusing on the male spouses’ education exclusively, as that may be more exogenous than female education. The results are robust to this modification. Also, we replaced education outcomes observed for adults by educational choices at age 10. In this setting, we do not observe any statistically significant treatment effects.

We also generated the estimation results when each of the limitations was restricted individually. The results are very similar.

We also considered the SOEP data with the extended sample definition in robustness tests. Again, the estimates of the treatment effects remain insignificant both for first and second births.

This comparison is not plausible for couples with one child where we expect the positive treatment effect among those with high income. As high-education and high-income couples are not likely to be on (means-tested) welfare, we do not use the control group of welfare recipients to test our second hypothesis.

We also estimated the timing effect for first births. Based on the Mikrozensus data, we obtain significant negative effects of the reform on maternal age at first birth, which were highly significant with the narrow definition of education and statistically insignificant and smaller with the broad definition. This suggests that the lack of a positive fertility effect for first births is not due to a postponement of births. If the reform brought about a reduced age at motherhood, it is possible that the lack of a short-run positive fertility effect for first births will be accompanied by a long-run increase in completed fertility.

References

Baughman R, Dickert-Conlin S (2003) Did expanding the EITC promote motherhood? Am Econ Rev 93(2):247–251

Baughman R, Dickert-Conlin S (2009) The earned income tax credit and fertility. J Popul Econ 22(3):537–563

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family, Enlarged edn. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bick A (2016) The quantitative role of child care for female labor force participation and fertility. J Eur Econ Assoc 14(3):639–668

BMF (Bundesministerium für Finanzen) 2008 Datensammlung der Steuerpolitik 2007, edition of July 2008. Bundesministerium der Finanzen, Berlin

BMFSFJ (Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend) (2005) Zwölfter Kinder- und Jugendbericht. Publikationsversand der Bundesregierung, Rostock

BMFSFJ (Bundesministerium für Familien, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend) 2008 Dossier: Kindergeld in Deutschland - Familien wirksam fördern. Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, Berlin

Brewer M, Ratcliffe A, Smith S (2012) Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. J Popul Econ 25(1):245–266

Bundeskindergeldgesetz 1995 Edition of October 11th, 1995. In: Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 1995 Teil I, S. 1378

Bundessozialhilfegesetz 1991 Edition of January 10th, 1991. In: Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 1991 Teil I, S. 105, § 77 (1)

Cigno A (1986) Fertility and the tax-benefit system: a reconsideration of the theory of family taxation. Econ J 96(384):1035–1051

Cigno A, Casolaro L, Rosati FC (2003) The impact of social security on saving and fertility in Germany. Finanzarchiv 59(2):189–211

Cohen A, Dehejia R, Romanov D (2013) Financial incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 95(1):1–20

Conrad C, Lechner M, Werner W (1996) East German fertility after unification: crisis or adaptation? Popul Dev Rev 22(2):331–358

Crump R, Goda GS, Mumford KJ (2011) Fertility and the personal exemption: comment. Am Econ Rev 101(6):1616–1628

Cygan-Rehm K (2014) Immigrant fertility in Germany: the role of culture. Schmollers Jahrbuch J Appl Sci Stud 134(3):305–340

Ermisch JF (2003) An economic analysis of the family. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Francesconi M, van der Klaauw W (2007) The socioeconomic consequences of “in-work” benefit reform for British lone mothers. J Hum Resour 42(1):1–31

Fuchs Benjamin, Schwientek Caroline 2016 Public child care and fertility in Germany. In: Schwientek Caroline (ed) Essays on education and family economics. Dissertation, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg

Gauthier AH (2007) The impact of family policy on fertility in industrialized countries: a review of the literature. Popul Res Policy Rev 26(3):323–346

Goldstein JR, Kreyenfeld M (2011) Has East Germany overtaken West Germany? Recent trends in order-specific fertility. Popul Dev Rev 37(3):453–472

González L (2013) The effect of a universal child benefit on conceptions, abortions, and early maternal labor supply. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(3):160–188

Guest R, Parr N (2013) Family policy and couples’ labour supply: an empirical assessment. J Popul Econ 26(4):1631–1660

Haan P, Wrohlich K (2011) Can child care policy encourage employment and fertility? Evidence from a structural model. Labour Econ 18(4):498–512

Havnes T, Mogstad M (2011) Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment. J Public Econ 95(11–12):1455–1465

HM Treasury 2010 Press Release Oct.,4 2010: chancellor announces reforms to the welfare system. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-announces-reforms-to-the-welfare-system [last access 2016-May-23]

Kinder- und Jugendhilfegesetz 1992 edition of July 27th, 1992. In: Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 1992 Teil I, S. 1400

Kluth S, Gasche M (2015) Ersatzraten in der Gesetzlichen Rentenversicherung (Replacement Rates in teh German Statutory Pension System). J Econ Stat (Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik) 235(6):553–583

Laroque G, Salanié B (2004) Fertility and financial incentives in France. CESifo Econ Stud 50(3):423–450

Laroque G, Salanié B (2014) Identifying the response of fertility to financial incentives. J Appl Econ 29(2):314–332

Lüdeke R, Werding M (1996) Die Reform des Dualen Familienlasten- bzw. Familienleistungsausgleichs 1996. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik Econ Stat 215(4):419–443

Luthen H (2016) Rates of return and early retirement disincentives: evidence from a German pension reform. Ger Econ Rev 17(2):206–233

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Moffitt R (1998) The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In: Moffitt R (ed) Welfare, the family and reproductive behavior: research perspectives. National Academy, Washington, pp 50–97

OECD 2014 OECD Family Database - PF1.3 Family cash benefits, www.oecd.org/els/soc /PF_1_3_Family_Cash_Benefits_Jul2013.pdf [last access 07 May 2016]

Rainer, Helmut, Stefan Bauernschuster, Natalia Danzer, Timo Hener, Christian Holzner, and Janina Reinkowski, 2012, Kindergeld, ifo Forschungsberichte, München

Reuters 2014 French government under fire over family benefit cuts, http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-france-benefits-idUKKCN0I60KY20141017 [last access 2016-May-23]

Schroedter JH, Lechert Y, Lüttinger P (2006) Die Umsetzung der Bildungsskala ISCED-1997 für die Volkszählung 1970, die Mikrozensus-Zusaterhebung 1971 und die Mikrozensen 1976–2004 (Version 1), mimeo. ZUMA, Mannheim

STBA (Statistisches Bundesamt) 2016 Sozialleistungen - Elterngeld und Kindergeld, https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Soziales/Sozialleistungen/Elterngeld/Tabellen/Kindergeld/EmpfaengerAusgaben.html [last access 2016-July-08]

Suzuki Toru 2013 Low fertility and population aging in Japan and Eastern Asia. Springer Briefs in Population Studies, Tokyo et al

Tamm M (2010) Child benefit reform and labor market participation. J Econ Stat (Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik) 230(3):313–327

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch J Appl Soc Sci Stud 127:139–169

Whittington LA, Alm J, Elizabeth Peters H (1990) Fertility and the personal exemption: implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. Am Econ Rev 80(3):545–556

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments received from two anonymous referees and the editor, at the 2016 CESifo conference on Employment and Social Protection, the BGPE research workshop in Augsburg, the annual ESPE conference in Berlin, and a LASER seminar in Nürnberg. We thank David M. Blau, Kamila Cygan-Rehm, Dominique Lemmermann, Rebecca Schrader, and Caroline Schwientek for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Appendices

Appendix 1 Additional descriptives and estimation results

Average and marginal tax rates before and after the 1995 income tax reform. Source: Own calculations based on Lüdeke and Werding (1996)

Appendix 2 Evidence on third births

The reform of child benefits for third births replaced a highly non-linear benefit-by-income mapping:

We expect an increase in third-child fertility particularly for high-income households. The incentives in a small segment of the gross household income distribution (65–80,000 DM) decline substantially and for the lowest income households the reform generated only a small change.

Table 27 shows the Mikrozensus-based results when applying the baseline estimation strategy, i.e., separating treatment and control groups based on educational attainment. Overall, fertility does not rise after the reform, and in the treatment group of the highly educated, we even find a significant negative coefficient estimate which suggests a decline in fertility for this group. Table 28 shows the estimation results based on the SOEP data. The coefficient estimates for the treatment effects have large standard errors and do not show clear patterns across the two definitions of treatment and control groups.

As these effects are inconclusive, we investigated the underlying income distribution for households with two children already in the treatment (high education) and control group (low education) for both datasets. Figures 21, 22, 23, 24 describe the results. Clearly, the income distributions particularly based on the broad definitions of treatment and control groups are not very distinct. As this may generate a measurement error in our estimations, we replaced the education-based approach by directly using household incomes. First, we inspect the fertility response of two-child households in the bottom and top income quartiles, and then, we separately consider the group of households who lost the most due to the reform, as their third-child fertility might have declined.

Table 29 shows the estimates for income quartile-based regressions for two-child households. Here, the Mikrozensus estimates of the treatment effect lose statistical significance. In Table 30, we explicitly consider households as treatment group who are located in the critical range between 55,400 DM and 81,000 DM gross household income (39,600–52,800 DM net household income) where we expect to see a drop in fertility after the reform. Interestingly, this specification confirms the negative expected fertility effect based on the SOEP data. While the sample size of the SOEP sample is smaller, it may be more precise in depicting the appropriate income range, because it measures income in gross amounts. The net incomes provided by the Mikrozensus might be less appropriate, because they are only proxies for the corresponding gross earnings and also the limits in net amounts for which the reform has a positive or negative effect are approximated.

Income distribution of families with two children in treatment and control group (narrow definition)—Mikrozensus. Notes: We report income in net amounts, because the Mikrozensus does not contain information on gross income. The dashed lines represent the thresholds of 39,600 and 52,800 DM, which is the approximate range that that captures the two-child families for which the reform decreased the financial incentives to have third child. Source: Own calculations based on the Mikrozensus waves 1995, 1996, 1998, and 1999

Income distribution of families with two children in treatment and control group (narrow definition)—SOEP. Notes: The dashed lines represent the thresholds of 55,400 and 81,000 DM, which is the range that captures the two-child families for which the reform decreased the financial incentives to have third child. Source: Own calculations based on the SOEP waves 1992 to 1998

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riphahn, R.T., Wiynck, F. Fertility effects of child benefits. J Popul Econ 30, 1135–1184 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0647-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0647-y