Abstract

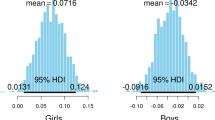

What happens to children’s long-run cognitive development when introducing universal high-quality childcare for 3-year-olds mainly crowds out family care? To answer this question, we take advantage of a sizeable expansion of publicly subsidized full-time high-quality childcare for 3-year-olds in Spain in the early 1990s. Identification relies on variation in the initial speed of the expansion of childcare slots across states. Using a difference-in-difference approach, we find strong evidence for sizeable improvements in children’s reading skills at age 15 (0.15 standard deviation) and weak evidence for a reduction in grade retentions during primary school (2.5 percentage points). The effects are driven by girls and disadvantaged children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this aspect, our paper contrasts with that of Black et al. (2012) in which the authors are able to isolate the effects of childcare subsidies on both parental and student outcomes.

Please refer to Appendix Table A.1 for an overview of the research on the impact of public childcare on children’s development. In addition, several recent studies evaluate the other side of the coin: the impact of maternal care on children’s development. Exploiting parental leave expansions, most studies do not find any significant effect on children’s long-run development (Baker and Milligan 2011; Dustmann and Schöenberg 2012; Liu and Oskar 2010; Rasmussen 2010). The exception is Carneiro et al. (2011) who find improvements in children’s long-run educational outcomes following a parental leave expansion in Norway. Likewise, a recent paper by Bettinger et al. (2013) exploits the introduction of an allowance paid to parents who do not utilize public care as an exogenous shock to maternal time devoted to their children in Norway. They also find positive effects on elderly siblings’ long-run educational outcomes.

About one third of children in primary school in Spain are enrolled in private schools. In this paper, private schools refer to escuelas concertadas for which the government subsidizes the staff costs (including teachers).

See Felgueroso et al. (2014) for an analysis of the effects of the primary and secondary school component of the reform on high school dropout rates.

Unfortunately, we only have information on enrollment rates and not on actual supply rates. In the context of rationed supply, enrollment rates should, however, resemble coverage rates quite closely.

Unfortunately, data disaggregated at the preschool level or at a lower regional level is not available.

While the pedagogical movements behind the LOGSE are close to those in Scandinavian countries, they have been viewed as an alternative to the test-oriented instruction legislated by the No Child Left Behind educational funding act in the USA or the reception class in the UK.

For our binary outcomes, we replicate our analysis using logit models, which yield similar results.

Due to perfect collinearity between the constant and the Post t dummy on the one hand and the PISA cohorts on the other hand, we omit two cohort dummies (2000 and 2009). Alternatively, we could omit the Post t dummy and include dummies for both “post reform” cohorts (see Section 7).

While we have administrative data on preschool enrollment at the lower level, we lack that information in PISA (in fact, gaining access to PISA data disaggregated at the state level is already quite hard). As such, our analysis relies on variation between states but ignores potential variation within states.

Following Berlinski and Galiani (2007), we estimate the proportion of public preschool seats offered in each state as the number of public preschool units available for 3- to 5-year-olds in each region times the average size of the classroom divided by the population of 3- to 5-year-olds in each state.

To account for the fact that there is a time- and state-varying trend in maternal employment that is positively correlated with the implementation of the reform but negatively correlated with maternal employment (or vice versa)—as shown by Nollenberger and Rodríguez-Planas (2011)—we add state-specific trends when the LHS variable is maternal employment. We abstain from doing so in our baseline estimates, as we only possess of PISA data at 4 points in time (every third year and not on an annual basis as it is the case for maternal employment data). Nevertheless, results for child outcomes including state-specific time trends are comparable in magnitude but less precise and are available upon request.

As the Ministry did not publish the enrollment rates at state level in the yearbooks, they were calculated by the authors as the ratio between the number of children enrolled in public and private schools (available at state level in the Education Statistics yearbooks) and the population of the corresponding age group and state from the Spanish Statistics Institute. (http://www.ine.es/jaxi/menu.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t20/p263/pob_91/&file=pcaxis). We check the consistency of our calculations comparing overlapping data for the school years 1992/1993 and 1993/1994.

Potentially, one could use PISA 2000 and 2003 and analyze whether we find evidence of a differential effect on cognitive development between youths in Basque Country and Navarra and the rest of Spain. However, because of the greater fiscal and political autonomy in these two regions, it is likely that other policies may have occurred at the same time, confounding the effect of the universal childcare policy.

As explained at the end of Section 3, we adjust the identification strategy to be comparable to the baseline strategy of the current paper.

We estimate the separate effect on the 1993/1994 and 1996/1997 cohorts and find similar coefficients (0.261 versus 0.256). As a consequence, we decided to pool both post-reform cohorts into one. Results when estimating our specification using the two cohorts separately are shown in Table 8 panel C and are discussed in Section 7.

Prior to the reform, the average employment rate of mothers of 3-year-olds was 35.7 % in fast-implementing states.

In addition, the migration flow by skill level is similar to the ones presented in the table and does not indicate any migration flows that would threaten our identification strategy.

Appendix Table A.2 explores additionally the sensitivity of our results to sequentially adding other (potentially endogenous) regional characteristics, individual characteristics, such as family characteristics (parents’ level of education and home possessions), type of school, and population density of the area of residence. While the effect on reading is robust across all specifications, the estimate on falling behind a grade becomes practically zero when regional characteristics are included. In this specification (column 2), the reform has a significant and beneficial effect on grade retention during secondary school. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that these additional control variables are likely to be affected by the reform and thus the estimated coefficients represent only net (off potential channels) effects of the reform on children’s cognitive long-run development.

While additional analysis adding a second-order polynomial of the number of available seats does not indicate any nonlinear impact of public childcare slots on children’s long-run cognitive development, using a step function instead does indicate that the effect is the effect of adding slots when the supply is still low (e.g., below the median and even in the lower tercile) is stronger than when the supply is rising. This evidence goes in line with the subgroup analysis by cohort which indicates stronger effects for the cohort 1990 when the supply of slots was still low than for the cohort 1993 when the supply of slots had already risen.

References

Adserà A (2004) Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. J Popul Econ 17(1):17–43

Amuedo-Dorantes C, de la Rica S (2009) The timing of work and work-family conflicts in Spain: who has a split work schedule and why? IZA discussion paper 4542

Baker M, Milligan K (2011) Maternity leave and children’s cognitive and behavioral development. NBER working paper 17105.

Baker M, Gruber J, Milligan K (2008) Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. J Polit Econ 116(4):709–745

Bauchmüller R, Gørtz M, Würtz-Rasmussen A (2014) Long-run benefits from universal high-quality preschooling. Early Child Res Q 29(4):457–470.

Berlinski S, Galiani S (2007) The effect of a large expansion in pre-primary school facilities on preschool attendance and maternal employment. Labour Econ 14(3):665–680

Berlinski S, Galiani S, Manacorda M (2008) Giving children a better start: preschool attendance and school-age profiles. J Public Econ 92(5):1416–1440

Berlinski S, Galiani S, Gertler P (2009) The effect of pre-primary education on primary school performance. J Public Econ 93(1–2):219–234

Bettinger E, Haegeland T, Rege M (2013) Home with mom: the effects of stay-at-home parents on children’s long-run educational outcomes. CESifo working papers 4274

Bettio F, Villa P (1998) A Mediterranean perspective on the breakdown of the relationship between participation and fertility. Cambridge J Econ 22(2):137–171

Black S, Devereux P, Loken K, Salvanes K (2012) Care or cash? The effect of child care subsidies on student performance. NBER working paper 18086

Blau D, Currie J (2006) Preschool, day care, and after school care: who's minding the kids? In: Hanushek E, Welsh F (eds) Handbook of economics of education vol 2. Amsterdam, North Holland Press, pp. 1163–278

Carneiro P, Løken K, Salvanes K (2011) A flying start? Maternity leave benefits and long run outcomes of children. IZA discussion paper 5793

Cascio E (2009) Do investments in universal early education pay off? Long-term effects of introducing into public schools. NBER working paper 14951

Datta Gupta N, Simonsen M (2010) Non-cognitive child outcomes and universal high quality child care. J Public Econ 94(1–2):30–42

Drange N, Havnes T, Sandsør A (2012) Kindergarten for all: long run effects of a universal intervention. Stat Norway DP 695

Duflo E (2001) Schooling and labor market consequences of school construction in Indonesia: evidence from an unusual policy experiment. Am Econ Rev 91(4):795–813

Dustmann C, Schöenberg U (2012) Expansions in maternity leave coverage on children long-term outcomes. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(3):190–224

Economist. Does subsidized preschool pay-off? 13 February 2013

Economist, Fighting over the kinder. 17 August 2013

El País, La LOGSE, 15 años después (by Elena Martín Ortega). 3 October 2005

Felfe C, Lalive R (2012) Early child care and child development: for whom it works and why. IZA Discussion Papers 7100.

Felgueroso F, Gutiérrez M, Jimenez S (2014) Why school dropout remained so high in the last two decades? The role of the educational law (LOGSE). IZA J Labor Policy 3:9, 9 May 2014

Fernández-Kranz D, Rodríguez-Planas N (2011) The part-time penalty in a segmented labor market. Labour Econ 18(5):591–606

Fitzpatrick M (2008) Starting school at four: the effect of universal pre-kindergarten on children’s academic achievement. BE J Econ Anal Poli 8(1):1–38

Gathmann C, Saß B (2012) Taxing childcare: effects on family labor supply and children. IZA discussion paper 6640

Gormley W Jr, Gayer T (2005) Promoting school readiness in Oklahoma. An evaluation of Tulsa’s pre-k program. J Hum Resour 3:533–558

Gutierrez-Domenech M (2005) Employment transitions after motherhood in Spain. Labour 19:123–148

Havnes T, Mogstad M (2011) No child left behind: subsidized child care and children’s long-run outcomes. Am Econ J Econ Policy 3:97–129

Lenneberg, E (1964) The capacity of language acquisition. In: J Fodor and J Katz (eds) The structure of language. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp 579–603

Liu Q, Oskar S (2010) The duration of paid parental leave and children’s scholastic performance. BE J Econ Anal Poli 10(1):1935–1682

Loeb S, Bridges M, Bassok D, Fuller B, Rumberger R (2007) How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Econ Educ Rev 26:52–66

LOGSE, Ley Orgánica 1, 1990 de Ordenación General del Sistema Educativo, 03.10.2013, BOE No. 238, 28927–28942

Magnuson K, Ruhm C, Waldfogel J (2007) Does prekindergarten improve school preparation and performance? Econ Educ Rev 26(1):33–51

Montessori M (1963) The secret of childhood. Ballentine Books, New York

New York Times. German Lawmakers Spar Over Child Care Subsidy, by Melissa Eddy. 6 Jun 2012

Nollenberger N, Rodríguez-Planas, N (2011) Child care, maternal employment and persistence: a natural experiment from Spain. IZA discussion paper 5888

OECD (2006). PISA 2006 science competencies for tomorrow’s world

Rasmussen A (2010) Increasing the length of parents’ birth-related leave: the effect on children’s long-term educational outcomes. Labour Econ 17(1):91–100

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor, Erdal Tekin, and three anonymous referees for helpful comments that greatly improved the paper. The authors are also grateful to Manuel Bagues, Paul Devereux, Susan Dinarsky, Maria Fitzpatrick, Libertad González, Lídia Farré, Michael Lechner, Oskar Nordström Skans, Björn Öckert, Xavi Ramos, Antonio Cabrales, Ismael Sanz Labrador, Uta Schönberg, Anna Sjögren, Anna Vignoles, Conny Wunsch, Natalia Zinovyeva, as well as participants from the V INSIDE-MOVE, NORFACE, and CReAM Workshop on Migration and Labor Economics, the III Workshop on Economics of Education “Improving Quality in Education,” the CESifo Area Conference on the Economics of Education, the RES Annual Meeting, the SOLE Annual Meeting, the ESPE Annual Meeting the EALE Annual Meeting as well as seminars at DIW, IFAU, University College Dublin, Ludwigs-Maximilians Universität, and University of St Gallen. The authors also would like to thank the Spanish Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa (INEE) del Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte for facilitating access to the geo-codes for PISA 2000 and Brindusa Anghel from FEDEA for her support with the Spanish Labor Force Survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Erdal Tekin

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Felfe, C., Nollenberger, N. & Rodríguez-Planas, N. Can’t buy mommy’s love? Universal childcare and children’s long-term cognitive development. J Popul Econ 28, 393–422 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0532-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0532-x