Abstract

Many studies have suggested that there is an inverse relationship between education and number of children among women from sub-Saharan Africa countries, including Malawi. However, a crucial limitation of these analyses is that they do not control for the potential endogeneity of education. The aim of our study is to estimate the role of women’s education on their number of children in Malawi, accounting for the possible presence of endogeneity and for nonlinear effects of continuous observed confounders. Our analysis is based on micro data from the 2010 Malawi Demographic Health Survey, and uses a flexible instrumental variable regression approach. The results suggest that the relationship of interest is affected by endogeneity and exhibits an inverted U-shape among women living in rural areas of Malawi, whereas it exhibits an inverse (nonlinear) relationship for women living in urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As a non-exhaustive list of policies, we can cite (a) compulsory primary education, (b) investment and improvements in the quality of the school infrastructure, (c) efforts to balance the teacher-student ratio, and (d) support for the purchase of school supplies for students and teachers (e.g. textbooks, pens, pencils).

References

Angeles G, Guilkey DK, Mroz TA (2005) The effects of education and family planning programs on fertility in Indonesia. Econ Dev Cult Change 54:165–202

Bailey M (1989) Female education and fertility in rural Sierra Leone: a test of the threshold hypothesis. Can Stud Popul 16:87–112

Basu MA (2002) Why does education lead to lower fertility? A critical review of some of the possibilities. World Dev 30:1779–1790

Blanc A, Rutenberg N (1990) An assessment of the quality of data on age at first sexual intercourse, age at first marriage, and age at first birth in the Demographic and Health Surveys Assessment of DHS-I Data Quality. Institute for Resource Development, Columbia. Macro System 3979

Bhalotra S, Rawlings SB (2011) Intergenerational persistence in health in developing countries: the penalty of gender inequality? J Public Econ 95:286–299

Birdsall MN, Griffin CC (1988) Fertility and poverty in developing countries. J Policy Model 10:29–55

Bound J, Jaeger DA, Baker RM (1995) Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. J Am Stat Assoc 90:443–450

Chen Y, Li H (2009) Mother’s education and child health: is there a nurturing effect? J Health Econ 28:413–1426

Chimombo JPG (2005) Quantity versus quality in education: case studies in Malawi. Int Rev Educ 51:155–172

Colclough C (1982) The impact of primary schooling on economic development: a review of the evidence. World Dev 10:167–185

Cragg JG, Donald SG (1993) Testing identifiability and specification in instrumental variable models. Economet Theor 9:222–240

Fan SC, Zhang J (2013) Differential fertility and intergenerational mobility under private versus public education. J Popul Econ 26:907–941

Gu C (2002) Smoothing spline ANOVA models. Springer, London

Heaton TB (2011) Does religion influence fertility in developing countries. Popul Res Policy Rev 30:449–465

IMF (International Monetary Fund) (2012) World economic outlook database for April 2012. http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=28. Accessed 1 May 2012

ICF International (2011) Demographic and health surveys methodology - questionnaires: household, woman’s, and man’s. MEASURE DHS phase III (project, implemented from 2008–2013), Calverton. http://www.measuredhs.com/publications/publication-DHSQ6-DHS-Questionnaires-and-Manuals.cfm. Accessed 1 May 2012

Kadzamira E, Rose P (2003) Can free primary education meet the needs of the poor? Evidence from Malawi. Int J Educ Dev 23:501–516

Kalipeni E (1997) Population pressure, social change, culture and Malawi’s pattern of fertility transition. Afr Stud Rev 40:173–208

Kazembe LN (2009) Modelling individual fertility levels in malawian women: a spatial semiparametric regression model. Stat Method Appl 18:237–255

Kravdal O (2000) A search for aggregate-level effects of education on fertility using data from Zimbabwe. Demogr Res 3:1–34

Lutz W, Samir KC (2011) Global human capital: integrating education and population. Science 333:587–592

MDHS (Malawi Demographic and Health Survey) (2012) Country quickstats. http://www.measuredhs.com/Where-We-Work/Country-Main.cfm?ctry_id=24&c=Malawi&Country=Malawi&cn=. Accessed 1 May 2012

MMDG (Malawi Millennium Development Goals) (2010) http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Malawi/MalawiMDGs2010Report.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2012

Manda S, Meyer R (2005) Age at first marriage in Malawi: a Bayesian multilevel analysis using discrete time-to-event model. J R Stat Soc Ser A 168:439–455

Martin TC (1995) Women’s education and fertility: results from 26 demographic and health survey. Stud Family Plann 26:187–202

Marra G, Radice R (2010) Penalised regression splines: theory and application to medical research. Stat Methods Med Res 19:107–125

Marra G, Radice R (2011a) A flexible instrumental variable approach. Stat Model 11:581–603

Marra G, Radice R (2011b) Estimation of a semiparametric recursive bivariate probit model in the presence of endogeneity. Can J Stat 39:259–6279

Marra G, Wood S (2012) Coverage properties of confidence intervals for generalized additive model components. Scand J Stat 39:53–74

Moyi P (2010) Household characteristics and delayed school enrollment in Malawi. Int J Educ Dev 30:236–242

National Statistical Office (NSO) and ICF Macro (2011) Malawi demographic and health survey 2010. NSO, Zomba/ICF, Calverton Macro

Osili UO, Long BT (2008) Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria. J Dev Econ 87:57–75

Palamuleni ME (2011) Socioeconomic determinants of age at marriage in Malawi. Int J Sociol Anthropol 3:224–235

Schafer MJ (2006) Household change and rural school enrollment in Malawi and Kenya. Sociol Quart 47:665–691

Sobotka F, Radice R, Marra G, Kneib T (2013) Estimating the relationship of women’s education and fertility in Botswana using an instrument variable approach to semiparametric expectile regression. J R Stat Soc Ser C 62:25–45

Staiger D, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65:557–586

Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N (2007) Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health 97:1233–1240

Strauss J, Thomas D (1995) Human resources: empirical modeling of household and family decisions. In: Behrman J, Srinivasan TN (eds) The handbook of development economics, 3A. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Strulik H, Vollmer S (2013) The fertility transition around the world. J Popul Econ. doi:10.1007/s00148-013-0496-2

Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ (2008) Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ 27:531–543

Wahba G (1983) Bayesian confidence intervals for the cross-validated smoothing spline. J R Stat Soc Ser B 45:133–150

Wood S (2006) Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. Chapman & Hall, London

Wooldrige JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge

Zanin L, Marra G (2012) A comparative study of the use of generalized additive model and generalized linear models in tourism research. Int J Tour Res 14:451–468

Zanin L, Radice R, Marra G (2014) A comparison of approaches for estimating the effect of women’s education on the probability of using modern contraceptive methods in Malawi. Soc Sci J. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2013.12.008

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to MEASURE DHS for having granted us permission to use the 2010 Malawi DHS data. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for many suggestions which stimulated us to conduct further analyses and helped to improve the presentation and quality of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Junsen Zhang

Appendix

Appendix

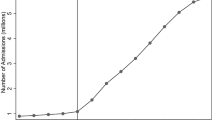

For the sake of completeness, we report below the estimation results that indicate the parametric (Table 3) and nonlinear (Fig. 6) effects for first-stage model (5).

Estimated nonlinear effects on the scale of the linear predictor for the continuous covariate age included in model (5); 95 % confidence intervals are represented by dashed lines. The rug plot, at the bottom of each graph, shows the covariate values

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanin, L., Radice, R. & Marra, G. Modelling the impact of women’s education on fertility in Malawi. J Popul Econ 28, 89–111 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-013-0502-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-013-0502-8