Abstract

This paper investigates the effects of foreign workers on labor market outcomes for Palestinian workers in the Israeli labor market. The paper utilizes a micro-dataset on the Palestinian labor force combined with time-series data on foreign workers in Israel. The data covers the period 1999–2003, a period in which Israel enforced a strict closure on labor (and goods) movement, particularly in 2001 and 2002. The evidence suggests that foreign workers in Israel do not affect Palestinian employment; however, an increase in the number of foreign workers in Israel tends to reduce Israeli wages paid to Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip. The Israeli closure policy appears to be the main cause for the substantial reduction in long-run Palestinian employment levels in Israel, not the presence of foreign workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

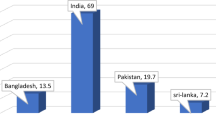

Foreign workers in Israel are mainly from the Far East (particularly Thailand), Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

Similar experiences could be found in the case of French workers commuting to Germany and Switzerland.

The overall non-response rate amounted to almost 10.4 percent, which is relatively low; a higher rate is rather common in an international perspective.

Men constitute the bulk of the Palestinian labor force, as labor force participation of women is low, 8% in the Gaza Strip and 10–12% in the West Bank.

The referred variable capturing if the individual is working in Israel also includes if the wage earner was working in Israeli settlements in the Palestinian territories.

The Gaza Strip experienced a more severe border closure policy, compared to the West Bank, where Palestinian workers were cutoff from their work in Israel during long periods.

Daily wages are expressed in New Israeli Shekels (NIS). During 1999–2003 the New Israeli Shekel was worth approximately 0.22–0.25 USD.

The plot does not consider the structural change in the Palestinian labor force during the period 1999–2003.

As seen in Table 2, over 80% of Palestinians employed in Israel during 1999–2003 worked in elementary occupations or as craft and related trade workers.

Following an Israeli policy decision after the signing of the Oslo accords in 1993, the Israeli government dramatically increased the number of permits to foreign workers from outside of the region. The aim of this policy was to decrease the former Israeli reliance on Palestinian workers, as those now became the responsibility of the newly established Palestinian Authority.

These findings are probably due to the problems associated with defining competing groups of immigrants and natives. In this paper, these problems can be overcome, as foreign guest workers and Palestinian workers from the West Bank and Gaza Strip actually compete in the Israeli labor market.

The experience of countries that have employed migrant workers at one time or another has been mixed. Recent examples of non-citizen labor include US employment of Mexicans, German employment of Turks, Western European employment of citizens of Southern and Eastern European nations, and Malaysians employed in Singapore.

A variable description is given in Appendix A.

They argue that the number of foreign work permits issued is a potential source of exogenous variation in the number of foreign workers actually employed in Israel. This is because there is a virtually infinite supply of unskilled workers from other countries that are willing to work in Israel, and there are lags and inefficiencies in the regulatory process that govern the issuance of permits, which creates a situation whereby the influx of foreign workers is not directly dependent of the Israeli labor market conditions.

An F test for joint significance of the identifying instruments suggests that these instruments have good explanatory power.

Although the Israeli policy of closure is applied to restrict all individuals who need to cross the borders, the border with Israel is not completely hermetically sealed. The random selection at the border crossing has created a situation of long border lines during time of closure. This is so especially in the Gaza Strip where the Israeli policy of closure is much closer to hermetic compared to in the West Bank.

Closure might also affect labor demand negatively, since closure may increase the uncertainty on behalf of the Israeli employers regarding Palestinian workers showing up at work or not. If employers are risk-averse, closure might in effect induce employers to change their hiring practices. However, since the Israeli policy of closure is instituted as a security instrument during political instability, which most likely has a negative impact on the Israeli economy, labor demand in Israel, may also exhibit a negative correlation with closure. In fact, the Israeli economy experienced a deep recession in 2001, a year in which days of closure peaked.

Since the correlation between the external and internal closure in the West Bank and Gaza Strip is very high, the effect of internal closure will be captured by our measure of closure in the estimations.

The F test for joint significance of the identifying instruments is 36.63, suggesting that the instruments are well correlated with the endogenous variable. Staiger and Stock (1997) propose that strong instruments should have a joint F statistic of around 10.

An F test was carried out to control for across-region equality. The test rejects that the estimated parameters from the West Bank regression are statistically equal to the estimated parameters from the Gaza Strip regression.

Additional specifications have been estimated to illuminate the impact of foreign workers on different types of skill group occupations in the economy. Given that Palestinian jobs in Israel are predominantly low-skilled, one might expect heterogeneous effects of foreign workers on different types of skill groups. However, as indicated by the results from these specifications, the effect of foreign workers does not significantly differ.

Only the ordinary least square estimates for Gazans employed in Israel are statistically different from zero, however, at the 10% level.

In view of the more recent building of the separation wall around the West Bank, it is plausible that this disparity may vanish as West Bank borders are also now more strictly sealed.

References

Altonji J, Card D (1991) The effects of immigration on the labor market outcomes of less-skilled natives. In: Abowd JM, Freeman RB (eds) Immigration, trade and labor markets. University of Chicago Press

Angrist J (1995) The economic returns to schooling in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Amer Econ Rev 85(5):1065–1087

Angrist J (1996) The short-run demand for palestinian labor. J Labor Econ 14(3):425–453

Angrist J (1998) The palestinian labor market between the Gulf War and autonomy. MIT Department of Economics, Working Paper 98-5

Aranki T (2006) The effect of israeli closure policy on wage earnings in the West Bank and Gaza strip, in wages, unemployment and regional differences – empirical studies of the Palestinian labor market. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Economics, Orebro University, Orebro, Sweden

Borjas G (1994) The economics of immigration. J Econ Lit 32(3):1667–1717

Borjas G (1999) The economic analysis of immigration. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3A. North Holland

Card D (1990) The impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami labor market. Ind Labor Relat Rev 43(2):245–257

Chiswick B (1999) Are immigrants favorably self-selected? An economic analysis. Amer Econ Rev 89(2):181–185

Daoud Y (2005) Gender gap in returns to schooling in Palestine. Econ Educ Rev 24(6):633–649

Daoud Y, Elkhafif M, Makhool B (2005) Policy framework and growth prospects of the Palestinian economy: a modeling perspective. Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS). Ramallah

Donald S, Lang K (2007) Inference with differences-in-differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat 89(2):221–233

Friedberg R (2001) The impact of mass migration on the Israeli labor market. Q J Econ 116(3):1373–1408

Friedberg R, Hunt J (1995) The impact of immigration on host country wages, employment and growth. J Econ Perspect 9(2):23–44

Friedberg R, Sauer R (2003) The effects of foreign guest workers in israel on the labor market outcomes of Palestinians from the West Bank and Gaza strip. The maurice falk institute for economic research in Israel, Discussion Paper No. 03.08

Greenwood M, Hunt G (1995) Economic effects of immigrants on native and foreign-born workers: complementarity, substitutability, and other channels of influence. South Econ J 61(3):1076–1097

Johnson G (1998) The impact of immigration on income distribution among minorities. In: Hamermesh DS, Bean FD (eds) Help or hindrance? The economic implications of immigration for African Americans. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 17–50

Kleiman E (1992) The flow of labour services from the West Bank and Gaza to Israel. Hebrew University Department of Economics, Jerusalem. Working Paper No.260

Locher L (2004) Immigration from the former soviet union to Israel: who is coming when? Eur Econ Rev 48(6):1243–1255

Makhool B, Daoud Y, Elkhafif M et al (2004) Integrated framework for Palestinian macroeconomics, trade and labour policy (Phase I): preliminary results. Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS). Ramallah

Miaari S, Sauer R (2006) The labor market cost of conflict: closures, foreign workers, and Palestinian employment and earnings. Institute for the Study of Labor IZA DP NO. 2282

Moulton B (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72(2):334–338

Pischke J, Velling J (1997) Employment effects of immigration to Germany: an analysis based on local labor markets. Rev Econ Stat 79(3):594–604

Ruppert Bulmer E (2003) The impact of Israeli border policy on the Palestinian labor market. Econ Dev Cult Change 51(3):657–676

Semyonov M, Lewin-Epstein N (1987) Hewers of wood and drawers of water: non-citizen Arabs in the Israeli labor market. ILR Press, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Staiger D, Stock J (1997) Instrumental variables with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586

Weiss Y, Sauer R, Gotlibovski R (2003) Immigration, search and loss of skill. J Labor Econ 21(3):557–592

Wooldridge J (2003) Cluster-sample methods in applied econometrics. Am Econ Rev 93(2):133–138

Wooldridge J (2006) Cluster-sample methods in applied econometrics: an extended analysis. Working paper. Michigan State University Department of Economics

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper have benefited from discussions with and suggestions from Lars Hultkrantz, Gunnar Isacsson, and Aysit Tansel. We also wish to thank Klaus F. Zimmermann and three anonymous referees for valuable comments. Thanks also go to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for providing the data. The views expressed in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Executive Board of Sveriges Riksbank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aranki, T.N., Daoud, Y. Competition, substitution, or discretion: an analysis of Palestinian and foreign guest workers in the Israeli labor market. J Popul Econ 23, 1275–1300 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0231-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-008-0231-6