Abstract

Purpose

Sepsis is a major health burden worldwide. Preclinical investigations in animals and retrospective studies in patients have suggested that inhibition of platelets may improve the outcome of sepsis. In this study we investigated whether chronic antiplatelet therapy impacts on the presentation and outcome of sepsis, and the host response.

Methods

We performed a prospective observational study in 972 patients admitted with sepsis to the mixed intensive care units (ICUs) of two hospitals in the Netherlands between January 2011 and July 2013. Of them, 267 patients (27.5 %) were on antiplatelet therapy (95.9 % acetylsalicylic acid) before admission. To account for differential likelihoods of receiving antiplatelet therapy, a propensity score was constructed, including variables associated with use of antiplatelet therapy. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the association of antiplatelet therapy with mortality.

Results

Antiplatelet therapy was not associated with sepsis severity at presentation, the primary source of infection, causative pathogens, the development of organ failure or shock during ICU stay, or mortality up to 90 days after admission, in either unmatched or propensity-matched analyses. Antiplatelet therapy did not modify the values of 19 biomarkers providing insight into hallmark host responses to sepsis, including activation of the coagulation system, the vascular endothelium, the cytokine network, and renal function, during the first 4 days after ICU admission.

Conclusions

Pre-existing antiplatelet therapy is not associated with alterations in the presentation or outcome of sepsis, or the host response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition caused by an injurious host response to infection with an estimated incidence of over 19 million cases per year worldwide [1, 2]. Sepsis plays a prominent role in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) where it is highly associated with morbidity and mortality [3]. During sepsis, triggering of inflammatory and coagulation cascades, together with endothelial damage, invariably leads to activation of platelets [4, 5]. Platelet activation can be further stimulated by direct interactions with pathogens [4, 6]. Platelets are essential components of primary hemostasis and in addition can aid the host in eliminating invading pathogens by facilitating a variety of bactericidal effector mechanisms [4, 6, 7]. However, during uncontrolled infection platelet activation contributes to sepsis complications [4, 8]. Indeed, several preclinical studies have shown beneficial effects of antiplatelet therapy in sepsis models [4].

Antiplatelet drugs such as clopidogrel or acetylsalicyclic acid are widely used in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial thrombosis. To date, there has been no randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of antiplatelet therapy in sepsis. Retrospective studies showed a beneficial effect of pre-existing therapy with an antiplatelet drug with respect to organ failure, duration of ICU and hospital stay, and mortality in critically ill patients [4, 8, 9]. However, most studies in critically ill patients with infection were small and/or included patient groups that were not matched for potential confounding factors, such as comorbidity and other chronic medication. In addition, the effect of antiplatelet therapy on the host response to critical illness has not been studied in patients.

The aim of the present prospective observational study was to determine the association between pre-existing antiplatelet therapy and presentation and outcome of sepsis, and induction of biomarkers providing insight into hallmark host responses, making use of a large well-defined cohort of patients admitted to the ICU. We hypothesized that chronic antiplatelet therapy may improve sepsis outcome by mitigating the derailed host response.

Methods

Study design, patients, and definitions

This study was conducted as part of the Molecular Diagnosis and Risk Stratification of Sepsis (MARS) project, a prospective observational study in the mixed ICUs of two tertiary teaching hospitals (Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam and University Medical Center Utrecht) in the Netherlands between January 2011 and January 2014 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01905033) [10, 11]. Both ICUs comply with the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines [12]. Dedicated observers prospectively collected the following data from all patients: demographics, comorbidities (including the Charlson comorbidity index [13]), chronic medication use, ICU admission characteristics (including the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV score and the acute physiology score [14]), and daily physiological measurements, severity scores (including Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores [15]), and culture results. Organ failure was defined as a SOFA score of 3 or greater, except for cardiovascular failure for which a score of 1 or more was used [16]. Shock was defined as the use of vasopressors (noradrenaline) for hypotension in a dose of 0.1 μg/kg/min during at least 50 % of the ICU day. The plausibility of infection was post hoc scored on the basis of all available evidence and classified on a 4-point scale (none, possible, probable, or definite) according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [17] and International Sepsis Forum consensus definitions [18], as described in detail previously [10]. Daily (at admission and at 6 A.M. thereafter) left-over plasma (obtained from blood drawn for patient care) was stored within 4 h at −80 °C. The medical ethical committees of both study centers gave approval for an opt-out consent method (IRB no. 10-056C). The Municipal Personal Records Database was consulted to determine survival up to 1 year after ICU admission.

For the current analysis we selected all patients included in the MARS study between January 2011 and July 2013 with sepsis, diagnosed within 24 h after admission, defined as a definite or probable infection [10] combined with at least one of general, inflammatory, hemodynamic, organ dysfunction, or tissue perfusion parameters derived from the 2001 International Sepsis Definitions Conference [19]. Readmissions, admissions for elective surgery, and patients transferred from another ICU were excluded, except for patients referred to one of the study centers on the day of admission.

Biomarker measurements

All measurements were done in EDTA anticoagulated plasma obtained within 24 h after admission (day 0) and days 2 and 4. Assays are described in the online supplement. Normal biomarker values were acquired from EDTA plasma from 27 age- and gender-matched healthy volunteers, from whom written informed consent was obtained.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed in R (v3.1.1). Baseline characteristics of study groups were compared with the Chi-square test for categorical variables and t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Mixed-effects models were executed to analyze repeated measurements. Propensity score matching and Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed as described in the online supplement. To account for random effects of propensity matching, appropriate tests were used in the propensity-matched cohort: paired t test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, McNemar test, stratified log-rank test, and Cox frailty model. Because of missing plasma samples in both groups (discharge, death, logistics), a paired test was not suitable to compare plasma sample measurements in the matched cohort. P values below 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patients

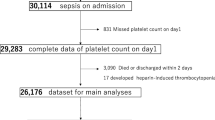

A total of 6994 admissions were included in the MARS study from January 2011 until July 2013, of which 1483 involved an admission diagnosis of sepsis. A total of 129 transfers from other ICUs and 250 readmissions were excluded; prior use of medication could not be retrieved in 44 cases. In addition, 88 patients admitted for elective surgery were excluded. As a result, 972 patients were included for analysis (523 in AMC, 449 in UMCU), of whom 267 (27.5 %) were on chronic antiplatelet therapy prior to ICU admission. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Acetylsalicylic acid was the most commonly used antiplatelet drug (95.9 %), whereas clopidogrel and dipyridamole were used by 16.1 and 12.4 % of the patients on antiplatelet therapy, respectively; 67 patients (25.1 %) were on more than one antiplatelet drug. Patients with antiplatelet therapy were older than those without, and more frequently men. As expected, cardiovascular disease was much more prevalent in antiplatelet therapy users, together with diabetes mellitus and COPD; non-users had a greater frequency of malignancies. In accordance, antiplatelet therapy users were also more frequently on other vasoactive drugs, including statins, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers. Sites of infection and causative pathogens did not differ between users and non-users of antiplatelet agents (Supplemental Table 1).

Considering the large baseline differences between users and non-users of antiplatelet drugs at baseline, we constructed a propensity-matched cohort. Thus 961 patients were assigned a propensity score for receiving antiplatelet therapy (99 % of all patients included); 11 patients were not given a score as a result of missing data. As a result of the unequal distribution of propensity scores between the groups (Supplemental Fig. 1), 150 of 267 antiplatelet users could be matched to non-users. The propensity-matched patients were similar with regard to comorbidity, chronic medication, and demographic distribution (Table 1).

Administration of antiplatelet therapy during ICU admission was dependent on the judgment of the medical team; at least one dose in the first 2 days of admission was received by 43.8 % of antiplatelet users in the unmatched cohort and by 40.0 % in the matched cohort.

Sepsis severity on admission

APACHE IV and SOFA scores and the presence of organ failure and shock were similar between chronic users and non-users of antiplatelet therapy, both in the unmatched and the propensity-matched cohort analyses (Table 1). Likewise, the use of supportive therapy (mechanical ventilation and renal replacement therapy) during the first 24 h after admission were similar between groups. Together these data suggest that the use of antiplatelet therapy does not influence the severity of sepsis upon admission to the ICU.

Sepsis outcomes

Table 2 and Fig. 1 show unadjusted outcomes of the unmatched and propensity-matched patients stratified according to the use of antiplatelet therapy. Irrespective of matching, antiplatelet therapy did not impact on the occurrence of organ failure or shock during ICU admission, or on mortality in the ICU, or at 30, 60, or 90 days. In a Cox proportional hazards model, APS was significantly associated with mortality rate at 30, 60, and 90 days in both the unmatched and matched cohort, whereas antiplatelet therapy was not. To confirm our findings, propensity scores were included in the regression model of the complete cohort, as a different method to adjust for propensity bias. Again, antiplatelet therapy was not associated with mortality, either at 30 days (Table 3), 60 days (Supplemental Table 2), or 90 days (Supplemental Table 3).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

In addition, we compared patients with only acetylsalicylic acid therapy to antiplatelet non-users, and patients receiving more than one antiplatelet drug with antiplatelet non-users. Outcomes from these patient groups were comparable to the initial cohort (data not shown). To evaluate the association between antiplatelet therapy and mortality in patients with septic shock we performed a subgroup analysis in this subset of patients (Supplemental Table 4). In addition, we included the interaction with antiplatelet therapy in the Cox proportional hazards models of the complete cohorts (Supplemental Table 5). These analyses did not change our findings: antiplatelet therapy was not associated with altered outcome. We defined septic shock as the use of vasopressors (noradrenaline) for hypotension for more than 50 % of the ICU day [20, 21]. We performed additional analyses in which shock was defined as the use vasopressors for hypotension for more than 6 h. Using this shock definition, we found that antiplatelet therapy was not associated with a different outcome (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7).

Host response biomarkers

To obtain insight into the association between chronic antiplatelet therapy and hallmark host responses, we measured 19 biomarkers providing insight into activation of coagulation (platelet counts, D-dimer, protein C, antithrombin), endothelial cell activation (sE-selectin, sICAM-1, angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2), renal injury (creatinine, NGAL, and cystatin C), release of proinflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-13), and release of metalloproteinases (MMP-8 and TIMP-1) in blood obtained within 24 h after admission (day 0) and days 2 and 4. Table 4 shows biomarker values in the propensity-matched cohort; biomarkers measured in the unmatched cohort are provided in Supplemental Table 8. As expected [22], biomarkers measured in sepsis patients differed significantly from those measured in controls (Supplemental Table 9). In the unmatched cohort platelet counts overall were higher in patients using antiplatelet therapy versus patients not on antiplatelet therapy (p = 0.002), in particular on days 0 and 2 of ICU admission, but this difference was not present anymore in the propensity-matched cohort. In addition, plasma creatinine was elevated in antiplatelet users at all timepoints in the unmatched but not in the matched cohort. IL-10 levels were slightly decreased in antiplatelet drug users compared to non-users, most notably on days 2 and 4; however, no significance remained in the propensity-matched cohort. Antiplatelet therapy did not alter the plasma levels of any of the other biomarkers in either the unmatched or the propensity-matched cohort.

Discussion

Platelet activation has been implicated as an important component of the deregulated host response in sepsis, and accordingly, antiplatelet therapy exerted protective effects in preclinical sepsis models [4, 8]. We here analyzed a prospectively enrolled cohort of 972 well-defined patients with sepsis and did not find an association between chronic antiplatelet therapy and severity of illness upon ICU admission, mortality, or biomarkers indicative of key host responses to severe infection. These data strongly argue against a beneficial effect of pre-existing antiplatelet therapy on sepsis severity or outcome in critically ill patients.

Four earlier retrospective studies investigated the effect of chronic antiplatelet therapy on mortality of patients with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock, reporting variable results [9, 23–25]. One study entailed patients admitted to a medical ICU with severe sepsis or septic shock, and it found no impact of chronic antiplatelet therapy after adjusting for the propensity to receive antiplatelet therapy and severity of illness as calculated by APACHE III score [23]. The other investigation encompassed patients admitted to the ICU with a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), of which a subgroup was classified as sepsis; propensity analysis showed a reduction in mortality in acetylsalicylic acid users in both the overall SIRS population and the sepsis subgroup [25]. While both studies adjusted for concurrent statin use in their propensity analyses, other chronic medication use was not taken into account [23, 25]. The third study performed regression analysis to establish the effect of chronic antiplatelet medication on sepsis outcome and reported an association between low-dose acetylsalicylic acid therapy with decreased ICU or hospital mortality [24]. Another report investigated the continuous use of acetylsalicylic acid during ICU stay and reported results similar to the previously mentioned study [26]. A very recent investigation used a medical claims database to report an association between chronic antiplatelet treatment and a reduced sepsis mortality [9]. Our study is different from these previous reports in several aspects. Most importantly, we prospectively enrolled patients and classified patients as having sepsis on the basis of strict diagnostic criteria. In addition, we performed propensity matching which enabled us to create comparable cohorts with respect to many important patient characteristics.

While platelets have been implicated in multiple inflammatory and procoagulant reactions, and thereby in the development of sepsis complications such as microvascular dysfunction, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiple organ failure [2, 4–6], knowledge of the effect of antiplatelet therapy on the host response to sepsis in patients is highly limited. Critically ill patients on acetylsalicylic acid had higher plasma fibrinogen levels in one study [24], which is difficult to interpret since fibrinogen is essential for fibrin formation and thus coagulation, but is also an acute phase protein. We measured 19 biomarkers indicative of important host response to sepsis on admission to the ICU, and at days 2 and 4. In the unmatched cohort we found some evidence of reduced platelet activation in patients on antiplatelet drugs, as reflected by higher platelet counts. However, the difference between users and non-users was not present anymore in the propensity-matched cohort. Besides their role in primary hemostasis, platelets facilitate activation of the coagulation system by assembling coagulation factor complexes on their surface and catalyzing the generation of thrombin [27]. In addition, platelets can enhance endothelial cell activation during sepsis via CD40 ligand on their cell membrane and platelet-secreted microparticles [4]. Nonetheless, we did not find any evidence for an effect of antiplatelet therapy on coagulation or endothelial cell activation in our study. Platelets can release several cytokines from their α-granules [6], and platelets can form complexes with leukocytes, thereby influencing leukocyte effector functions and cytokine secretion [28–30]. In accordance, long-term clopidogrel treatment was associated with reduced TNF-α and IL-13 levels in patients with cardiac disease undergoing non-emergent stenting [31] and several antiplatelet agents were shown to inhibit intracellular leukocyte TNF-α and IL-8 responses upon acute stroke [32]. However, in the current investigation antiplatelet therapy was not associated with statistically significant differences in the plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with sepsis. Moreover, antiplatelet therapy was not associated with alterations in MMP-8 or TIMP-1 levels, which were previously described to be elevated in patients with sepsis [33] and have been suggested to contribute to many inflammatory reactions during severe infection [34]. The similarity of biomarkers in antiplatelet users and non-users does not corroborate with the results from many preclinical studies showing benefit from antiplatelet therapy during infection or inflammation [4, 8]. Even in our well-defined cohort, sepsis patients are heterogeneous in terms of site and microbiology of the infection, disease severity, genetic background, age, and comorbidity, and plasma biomarker concentrations demonstrated a large inter-individual variability, which may explain the lack of effect by antiplatelet therapy. In addition, the dose at which antiplatelet therapy is administered to patients may be insufficient to alter the strong inflammatory and procoagulant responses induced by severe sepsis.

A strength of our study is the prospectively enrolled cohort in which patients were meticulously classified and followed daily. We performed propensity matching, which enabled us to specifically evaluate the effect of antiplatelet therapy, by catering for differences in baseline characteristics between users and non-users. Nonetheless, it remains possible that a bias remained as a result of unmeasured confounders, an important limitation of propensity score analyses. Considering that after propensity matching 150 patients per group remained to evaluate differences between those who did and those who did not use chronic antiplatelet therapy, the possibility of false negative results exists. However, the number of patients needed in the propensity-matched analysis to detect a statistically significant difference between groups with a power of 80 % would be more than 2000 per group for mortality and from more than 330 to more than 150,000 per group for individual biomarkers. While these numbers are difficult to achieve, they also raise doubt about the clinical and biological relevance of potential differences not revealed in our analyses. Additional limitations are the lack of information about the indication for, dosing of, and adherence to antiplatelet therapy; the lack of information about bleeding complications; and the fact that this study was performed in two centers in the Netherlands and may not reflect general ICU practice. Also, we were not able to investigate whether chronic antiplatelet therapy influences sepsis progression before ICU admission; with the current study we cannot rule out that antiplatelet therapy has beneficial effects in early stages of sepsis.

Conclusion

In this prospectively assembled cohort of 972 well-defined patients with sepsis we did not find an association between chronic antiplatelet therapy and severity of illness or outcome. Additionally, no differences in biomarkers indicative of key host responses to sepsis were found between patients who did and who did not receive chronic antiplatelet therapy. Our data strongly argue against a beneficial effect of pre-existing antiplatelet therapy on sepsis severity or outcome.

References

Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S et al (2010) Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet 376:1339–1346

Angus DC, van der Poll T (2013) Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 369:840–851

Timsit JF, Perner A, Bakker J et al (2015) Year in review in Intensive Care Medicine 2014: III. Severe infections, septic shock, healthcare-associated infections, highly resistant bacteria, invasive fungal infections, severe viral infections, Ebola virus disease and paediatrics. Intensive Care Med 41:575–588

de Stoppelaar SF, van ‘t Veer C, van der Poll T (2014) The role of platelets in sepsis. Thromb Haemost 112:666–677

Schouten M, Wiersinga WJ, Levi M et al (2008) Inflammation, endothelium, and coagulation in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol 83:536–545

Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr, Freedman J (2011) Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 11:264–274

Yeaman MR (2010) Platelets in defense against bacterial pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:525–544

Akinosoglou K, Alexopoulos D (2014) Use of antiplatelet agents in sepsis: a glimpse into the future. Thromb Res 133:131–138

Tsai MJ, Ou SM, Shih CJ et al (2015) Association of prior antiplatelet agents with mortality in sepsis patients: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Intensive Care Med 41:806–813

Klein Klouwenberg PM, Ong DS, Bos LD et al (2013) Interobserver agreement of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria for classifying infections in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 41:2373–2378

Klein Klouwenberg PM, van Mourik MS, Ong DS et al (2014) Electronic implementation of a novel surveillance paradigm for ventilator-associated events. Feasibility and validation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:947–955

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al (2013) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 39:165–228

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS et al (2006) Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 34:1297–1310

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al (1996) The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 22:707–710

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al (2014) Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 311:1308–1316

Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG et al (1988) CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control 16:128–140

Calandra T, Cohen J (2005) The international sepsis forum consensus conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 33:1538–1548

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC et al (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS international sepsis definitions conference. Crit Care Med 31:1250–1256

Scicluna BP, Klein Klouwenberg PM, van Vught LA et al (2015) A molecular biomarker to diagnose community-acquired pneumonia on intensive care unit admission. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192:826–835

Klein Klouwenberg PM, Cremer OL, van Vught LA et al (2015) Likelihood of infection in patients with presumed sepsis at the time of intensive care unit admission: a cohort study. Crit Care 19:319

Pierrakos C, Vincent JL (2010) Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 14:R15

Valerio-Rojas JC, Jaffer IJ, Kor DJ et al (2013) Outcomes of severe sepsis and septic shock patients on chronic antiplatelet treatment: a historical cohort study. Crit Care Res Pract 2013:782573

Otto GP, Sossdorf M, Boettel J et al (2013) Effects of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and atherosclerotic vascular diseases on the outcome in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Platelets 24:480–485

Eisen DP, Reid D, McBryde ES (2012) Acetyl salicylic acid usage and mortality in critically ill patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis. Crit Care Med 40:1761–1767

Sossdorf M, Otto GP, Boettel J et al (2013) Benefit of low-dose aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in septic patients. Crit Care 17:402

Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T (2006) Plasma and plasma components in the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 19:127–142

Xiang B, Zhang G, Guo L et al (2013) Platelets protect from septic shock by inhibiting macrophage-dependent inflammation via the cyclooxygenase 1 signalling pathway. Nat Commun 4:2657

Gudbrandsdottir S, Hasselbalch HC, Nielsen CH (2013) Activated platelets enhance IL-10 secretion and reduce TNF-alpha secretion by monocytes. J Immunol 191:4059–4067

Stephen J, Emerson B, Fox KA et al (2013) The uncoupling of monocyte–platelet interactions from the induction of proinflammatory signaling in monocytes. J Immunol 191:5677–5683

Antonino MJ, Mahla E, Bliden KP et al (2009) Effect of long-term clopidogrel treatment on platelet function and inflammation in patients undergoing coronary arterial stenting. Am J Cardiol 103:1546–1550

Al-Bahrani A, Taha S, Shaath H et al (2007) TNF-α and IL-8 in acute stroke and the modulation of these cytokines by antiplatelet agents. Curr Neurovasc Res 4:31–37

Lauhio A, Hastbacka J, Pettila V et al (2011) Serum MMP-8, -9 and TIMP-1 in sepsis: high serum levels of MMP-8 and TIMP-1 are associated with fatal outcome in a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Hypothetical impact of tetracyclines. Pharmacol Res 64:590–594

Vanlaere I, Libert C (2009) Matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets in infections caused by gram-negative bacteria and in septic shock. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:224–239

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Rolf H. H. Groenwold, MD, PhD (Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands) for statistical advice and the following members of the MARS consortium for participation in data collection: Friso M. de Beer, MD, Lieuwe D. J. Bos, PhD, Gerie J. Glas, MD, Roosmarijn T. M. van Hooijdonk, MD (Department of Intensive Care, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam), Mischa A. Huson, MD (Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam), David S. Y. Ong, MD, PharmD (Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology and Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands), Laura R. A. Schouten, MD (Department of Intensive Care, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam), Brendon P. Scicluna, PhD (Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam), Marleen Straat, MD, Esther Witteveen, MD, and Luuk Wieske, MD, PhD (Department of Intensive Care, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam).

Funding

This research was performed within the framework of CTMM, the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine (www.ctmm.nl), project MARS (Grant 04I-201). The sponsor CTMM was not involved in the design and conduction of the study; nor was the sponsor involved in collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Decision to submit the manuscript was not dependent on the sponsor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

A complete list of members of the MARS Consortium can be found in Acknowledgments section.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiewel, M.A., de Stoppelaar, S.F., van Vught, L.A. et al. Chronic antiplatelet therapy is not associated with alterations in the presentation, outcome, or host response biomarkers during sepsis: a propensity-matched analysis. Intensive Care Med 42, 352–360 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-4171-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-4171-9