Abstract

Purpose

Although strong evidence documents the elevated prevalence of both substance use and mental health problems among sexual minorities (i.e., gay, lesbian, and bisexuals), relatively less research has examined whether risk of the co-occurrence of these factors is elevated among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals. The object of this study was to (1) explore sexual orientation-based differences in substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence in a representative sample in Sweden, and (2) examine if greater exposure to stressors, such as discrimination, victimization/threats, and social isolation, could explain these potential disparities and their co-occurrence.

Methods

Data come from the cross-sectional Swedish National Public Health Survey, which collected random samples of individuals (16–84 years of age) annually from 2008 to 2015, with an overall response rate of 49.7% (n = 79,568 individuals; 1673 self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual). Population-level sexual orientation differences in substance use (i.e., alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis) and psychological distress were examined.

Results

Our findings showed significantly elevated prevalence of high-risk alcohol use, cannabis use, and daily tobacco smoking, among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals. These substantial disparities in substance use more often co-occurred with psychological distress among sexual minorities than among heterosexuals. The elevated risk of co-occurring psychological distress and substance use was most notable among gay men relative to heterosexual men (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.65, CI 1.98, 3.55), and bisexual women relative to heterosexual women (AOR = 3.01, CI 2.43, 3.72). Multiple mediation analyses showed that experiences of discrimination, victimization, and social isolation partially explained the sexual orientation disparity in these co-occurring problems.

Conclusions

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that sexual minorities experience multiple threats to optimal health and points toward future interventions that address the shared sources of these overlapping health threats in stigma-related stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent studies have shown significant sexual orientation differences in the prevalence of alcohol abuse, recreational drug use, and tobacco smoking, with sexual minorities (i.e., those self-identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual [LGB] or those reporting same-sex sexual experiences) reporting greater substance use than heterosexuals [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Large differences also exist in mental health problems such as depression, anxiety disorders, and suicide attempts between sexual minorities and heterosexuals [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. These disparities in substance use and mental health problems emerge early in development, persists across the life course, and expose sexual minorities to a greater risk of potentially avoidable diseases than heterosexuals [16,17,18,19,20].

Although strong evidence documents the elevated prevalence of both substance use and mental health problems among sexual minorities, relatively less research has examined whether risk of the co-occurrence of these factors is elevated among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals [21]. However, studies suggest that poor mental health and substance use frequently co-occur among sexual minority individuals [21,22,23], potentially due to their shared source in sexual minorities’ exposure to stigma [24].

Stigma, including exposure to unequal treatment and other forms of discrimination, has been argued to represent a fundamental cause of adverse health conditions [25]. Stigma compromises health, because it compromises access to the knowledge, prestige, power, and supportive social connections necessary to prevent disease [20]. Notably, stigma as a fundamental cause of poor health affects not just isolated disease conditions, but many. A complementary theory of poor health among stigmatized populations—syndemic theory—suggests that, against stigmatizing social backdrops, certain disease epidemics co-occur and perpetuate each other [26]. In fact, studies have shown that sexual minorities experience higher rates of depression, substance use disorder, suicidality, and exposure to violence, and that these adverse outcomes are associated with stigma [27,28,29,30,31,32].

In the case of sexual minority men, accumulating evidence suggests that structural stigma in the form of discriminatory laws and policies toward sexual minorities, interpersonal stigma in the form of victimization and discrimination, and intrapersonal stigma in the form of internalized homophobia and anxious expectations of rejection are all associated with substance use and mental health problems [6, 18, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. However, less clear is whether risk of the co-occurrence of substance use and mental health problems is elevated among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals and whether sexual minorities’ disproportionate exposure to stigma and discrimination explain their increased risk of these co-occurring health risks.

The present study takes advantage of the data available within the representative population-based Swedish National Public Health Survey conducted between 2008 and 2015. Pooling eight consecutive years of survey data provides a large enough sample size to address existing gaps in knowledge regarding sexual orientation disparities in substance use and co-occurring mental health problems. Specifically, the large sample size and representative data structure permitted us to pursue the following research questions: (a) are substance use (i.e., high-risk alcohol use, use of cannabis, and daily smoking) and psychological distress more prevalent among sexual minority individuals than among heterosexuals? (b) Is the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress more common among sexual minorities than among heterosexuals; and (c) can greater exposure to stressors, such as discrimination, victimization/threats, and social isolation, explain or partially explain the elevated prevalence of substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence among sexual minorities? (d) Are sexual orientation disparities in co-occurring substance use and psychological distress greater for bisexuals compared to gays/lesbians, for sexual minority men compared to women, and for adolescent/young adult sexual minorities compared to adult sexual minorities?

Methods

Participants

Each year between 2008 and 2015, the Public Health Agency of Sweden collected nationwide population-based health surveys in independent unrestricted random samples of the general population in Sweden (20,000 individuals each year), ages 16–84. A total of 79,568 individuals responded across the eight surveys. Identical modes of data collection, questions, and survey administration were used in all years and participants were offered the option to respond to the questions via either paper-and-pencil mailed questionnaires or self-administered web surveys. Data from each annual survey were pooled into one data set. The response rate varied between 48.1 and 60.8% each year with an overall response rate of 49.7%. The response rate was higher among women and older age groups. In addition to a question regarding sexual orientation, the survey assessed socio-demographic background, health status, and health determinants, and was supplemented with data from administrative national registries regarding income, ethnicity, and urbanicity. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (No. 2013/2200-31/2).

Measures

Sexual orientation Individuals’ sexual orientation was classified based on self-identification using the following item: “What is your sexual orientation?” with the response categories: “heterosexual,” “bisexual,” “homosexual,” and “not sure.” The rate of non-response for this question has continually decreased, from 6.9% in 2008 to 3.2% in 2015. In the total sample, 588 (0.7%) individuals self-identified as gay men/lesbian and 1085 (1.4%) self-identified as bisexual. The proportion of respondents reporting an LGB identity remained stable over the 10-year period (the range for gay men/lesbian was 0.7–0.8% and for bisexuals 1.2–1.8%). We excluded 1382 (1.7%) individuals who responded that they were uncertain of their sexual orientation, as previous studies have shown that this group often consists of a heterogeneous mix of respondents in terms of sexual identity [45]. While some people do not know their sexual orientation because they are undecided, studies have indicated that the majority of people who choose such responses in population surveys are doing so because they did not understand the question [46]. Those who responded that they were “not sure” of their sexual orientation did not differ significantly regarding gender and age, but were more often born outside of Sweden, had lower income and education, were less often married or partnered, and were more likely to report poor mental health as compared to those reporting being heterosexual (all associations were significant at P < 0.001).

Socio-demographic variables Socio-demographic factors, including age, annual individual income, ethnicity (i.e., nation of birth categorized into geographic regions), relationship status, and urbanicity (i.e., living in larger city, smaller city, or rural community), were collected from national registries and linked to the questionnaire data, which also included self-reported relationship status (i.e., living with partner versus single). These covariates were chosen, because they were significantly associated with sexual orientation and with psychological distress in bivariate models and could therefore serve as potential confounders.

Substance use In the current study, three forms of substance use were analyzed: high-risk alcohol consumption, cannabis use, and tobacco use. All of these were coded as dichotomous variables. Two different measures were used to categorize respondents into high-risk versus non-high-risk consumers of alcohol. The first concerned average frequency of heavy drinking during the past 12 months, based on one question regarding drinking at least one bottle of wine or equivalent during one occasion. The second measure concerned total weekly amount of alcohol consumed on average during the past 12 months, measured as number of “drinks” (defined as 33 centiliters [cl] of beer, 10–15 cl of wine, 4 cl of hard liquor, or equivalent). Male respondents were categorized as high-risk consumers of alcohol if they either reported at least monthly heavy alcohol consumption or reported an average weekly consumption of more than 14 drinks, in accordance with the threshold for hazardous weekly alcohol consumption proposed by the Swedish National Institute of Public Health [47]. Women were similarly categorized as high-risk consumers of alcohol if they either reported at least monthly heavy alcohol consumption or reported an average weekly consumption of more than nine drinks. Cannabis use was assessed with one question regarding frequency of cannabis use during the past 12 months, which was categorized based on any past-12-month use (use/no use). One question regarding daily tobacco smoking was used to categorize the respondents into current daily smokers versus non-smokers.

Psychological distress The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12) was used to assess recent symptoms of psychological distress. The GHQ12 is a frequently used measure of current mental health and focuses on two major types of symptoms: anhedonia (e.g., “Over the past few weeks, have you been able to enjoy your normal day-to-day activities?” with response alternatives: ‘more so than usual’; ‘same as usual’; ‘less so than usual’; and ‘much less than usual’) and depressed mood (e.g., “Over the past few weeks, have you been feeling unhappy and depressed?” with response alternatives: ‘not at all’; ‘no more than usual’; ‘rather more than usual’; and ‘much more than usual’). It has shown adequate validity in both clinical and general populations and has demonstrated satisfactory sensitivity and specificity for predicting current diagnosis of major depression [48, 49]. Consistent with prior research [49], we created a dichotomous variable (GHQ12 ≤ 3: ‘no current psychological distress’; GHQ12 ≥ 4: ‘current psychological distress’).

Stress exposure Three questions were used to assess exposure to discrimination, victimization/threats, and social isolation. Perceived discrimination was assessed with one question: “During the past three months, have you been treated in a way that made you feel discriminated against [yes/no]?” Two questions assessed experiences of victimization and threat of assaults: “During the past 12 months, have you ever been physically assaulted [yes/no]?” and “During the past 12 months, have you ever been exposed to threats or threats of violence, severe enough to make you scared [yes/no]?” Respondents were categorized as having versus not having been exposed to discrimination or victimization. Two questions were used to assess social isolation—one question regarding emotional social support: “Do you have anyone you can share your innermost feelings with and confide in [yes/no]?” and one question regarding instrumental social support: “Can you get help from any person or persons if you have practical problems or are ill? e.g. get advice, borrow things, help with shopping, repairs etc. [yes/no].” Respondents were categorized as socially isolated if they lacked both emotional and instrumental social support or not socially isolated if they reported at least one type of support.

Statistical analysis

After examining descriptive statistics, sexual orientation differences in substance use and psychological distress were analyzed using logistic regression. Post-stratification weights were used to adjust for selection probabilities and non-response to generate nationally representative estimates of prevalence and associations. The analyses were adjusted for age, income, education, urbanicity, relationship status, and country of birth. Dummy variables were created so as to indicate the presence of a combination of any substance use (high-risk alcohol consumption, use of cannabis, and daily smoking) and elevated psychological distress. We then used these dummy variables to explore sexual orientation differences in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress using logistic regression. Only respondents with complete data on each outcome variable were included in analyses, but missing values on outcome variables were infrequent and varied between 0.6% (tobacco use) and 2.5% (psychological distress).

We then examined whether stress exposure (i.e., discrimination, victimization/threats, social isolation) explains or partially explains elevated prevalence of substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence among sexual minorities. We conducted three separate multiple mediation analyses, one for each outcome variables. For all three multiple mediation analyses, all three proposed mediating variables were included (i.e., discrimination, victimization, and social isolation). To statistically test the mediating effects, we calculated the indirect effects of exposure to stressors (i.e., discrimination, victimization/threats, and social isolation) as mediators of the link between sexual orientation and our outcomes. A significant indirect effect (P < 0.05) was interpreted as evidence of mediation.

In addition to the main analyses, effect modification by gender and age was examined in secondary subgroup analyses. Stratified analyses were performed if the interaction between sexual orientation and these variables was significant.

Data analyses were conducted using both SPSS (version 24) and Mplus (version 8).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents socio-demographic characteristics and exposure to stressors in the total sample and stratified by sexual orientation. Gay men/lesbians were more likely to be male, younger, university educated, born outside of Sweden, living in a larger city, and living without a partner, and have lower income, as compared to heterosexuals. Bisexuals were more likely to be female, younger, born outside of Sweden, living in a larger city, living without a partner, and having lower income, compared to heterosexuals. All associations between socio-demographic factors and sexual orientation were significant at P < 0.001 using Chi square tests for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. Concerning exposure to stress, both sexual minority groups (i.e., gay men/lesbians and bisexuals) reported greater exposure to discrimination and victimization/threats during the past 12 months than heterosexuals; and they were more likely to report being socially isolated (all P < 0.001).

Sexual orientation disparities in substance use, psychological distress, and co-occurring substance use and psychological distress

Table 2 presents sexual orientation disparities in substance use and psychological distress. Gay men/lesbians had elevated risk of high-risk alcohol consumption, cannabis use, daily tobacco smoking, and psychological distress compared to heterosexuals. Bisexuals had elevated risk of cannabis use, daily smoking, and psychological distress compared to heterosexuals. Furthermore, the last column of Table 2 presents sexual orientation disparities in co-occurring substance use and psychological distress. Both gay men/lesbians and bisexuals had elevated risk of co-occurring psychological distress and substance use compared to heterosexuals.

Stress exposure as a mediator of sexual orientation disparities in substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence

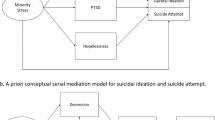

To explore the indirect effect of stress exposure on substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence, a set of serial multiple mediation analyses was conducted (Fig. 1). The analyses showed significant indirect mediating effects of social isolation in the association between sexual orientation and substance use among gay men/lesbians, and of both social isolation and victimization/threats among bisexuals. The analyses also showed significant indirect mediating effects of both discrimination and social isolation in the association between sexual orientation and psychological distress among gay men/lesbians and bisexuals. Furthermore, the associations between sexual orientation and the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress were significantly mediated through all three mediators (i.e., discrimination, victimization, and social isolation). The effects were all in the same direction, indicating that the elevated risk of substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals, could partially be explained by sexual minorities’ elevated exposure to discrimination, victimization/threat, and social isolation.

Effect modification by gender and age

To determine if sexual orientation disparities in substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence differed by gender and age, analyses of interactions between sexual orientation and gender, as well as sexual orientation and age, were performed. For significant effects, stratified analyses are presented in Table 2. The prevalence of substance use, psychological distress, and their co-occurrence is presented in Table 3 stratified by sexual orientation, gender, and age. Gender and age were found to be a significant effect modifier of several outcomes. In stratified analyses, the sexual orientation disparity in high-risk alcohol consumption was only significant among bisexual, compared to heterosexual, women, but not for bisexual, compared to heterosexual, men. Further, the sexual orientation disparity in cannabis use was greater among bisexual, compared to heterosexual, women than among bisexual, compared to heterosexual, men. The sexual orientation disparity in daily tobacco smoking was only significant among gay, compared to heterosexual, men but not among lesbian, compared to heterosexual, women. The sexual orientation disparity in psychological distress was greater among bisexual, compared to heterosexual, women than among bisexual, compared to heterosexual, men. Gender-stratified analyses of co-occurring psychological distress and substance use showed that the elevated risk of this co-occurrence was only present among gay men compared to heterosexual men, and not among lesbian women compared to heterosexual women. Further, the elevated prevalence of co-occurring substance use and psychological distress was larger among bisexual women compared to heterosexual women than among bisexual men compared to heterosexual men.

The sexual orientation disparity in psychological distress was greater among younger (16–34 years), compared to older (35–84 years), gay men/lesbians. The disparity in co-occurring substance use and psychological distress was also stronger among younger, compared to older, bisexuals.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the first population-based study to examine sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress. Our data, which came from national population surveys in Sweden repeated annually between 2008 and 2015, showed significantly elevated prevalence of high-risk alcohol use, cannabis use, and daily tobacco smoking among sexual minorities than among heterosexuals. Further, these substantial disparities in substance use more often co-occurred with psychological distress among sexual minorities than among heterosexuals. The elevated risk of co-occurring psychological distress with substance use was most notable among gay men relative to heterosexual men, and bisexual women as compared to heterosexual women. No such elevated risk existed among lesbian, compared to heterosexual, women.

In addition to showing evidence of elevated co-occurring prevalence of substance use and psychological distress among sexual minorities, our findings indicate that experiences of discrimination, victimization, and social isolation partially explain the sexual orientation disparity in these co-occurring problems. Experiences of discrimination, victimization, and social isolation were elevated among both gay men/lesbians and bisexuals, and partially explained the elevated prevalence of substance use, psychological distress, as well as the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress among sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals.

These results support two primary tenets of syndemic theory as applied to sexual minority health [26, 32], namely that psychosocial health conditions co-occur among this marginalized group and that this co-occurrence is at least partially explained by sexual minorities’ disproportionate exposure to social stressors. This study also offers some of the first evidence of syndemic theory applied to sexual minority women and suggests that co-occurring substance use and psychological distress are particularly likely to affect bisexual women. In fact, bisexual women evinced more than a three-time greater risk of co-occurring psychological distress and substance use than heterosexual women.

Other subgroup analyses partially confirm the increased disparity in substance use experienced by bisexual men and women compared to gay men/lesbians and heterosexuals reported elsewhere [7, 8, 50, 51], but expand these findings by showing an increased risk of co-occurring substance use and psychological distress. In contrast with previous findings, we did not find a gender difference in the sexual orientation disparity in high-risk alcohol consumption among gay men and lesbians [7, 8]. However, consistent with previous research, we found that the sexual orientation disparity in psychological distress is stronger among younger individuals; the present study finds that this age pattern extends to the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress, but only for bisexuals [52].

Results should be considered in light of several limitations. First, given that data were collected cross-sectionally at each assessment point, we are unable to establish the causal direction of effects. It is possible that their higher engagement in substance use puts sexual minority individuals at greater risk of exposure for discrimination and victimization, which subsequently confers risk for psychological distress. Only a prospective cohort design would allow future researchers to determine the temporal influence of minority stress exposure on substance use and its co-occurrence with psychological distress. Second, limited psychosocial measures in the datasets prevented the examination of additional potential mediators of the disparities found here. For instance, perhaps substance use coping motives or norms are particularly likely to explain the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress among certain sexual minority subgroups [53, 54]. Third, pooling data across several years also has limitations in that a small subset of individuals might have been included in more than one round of data collection However, we consider it unlikely that this limitation influenced our overall conclusions given the extremely low probability of being repeatedly sampled into one of the annual Swedish National Public Health Surveys. Finally, as with all population-based surveys, the current study also contained a substantial proportion of non-responders. It is possible that those who decided not to participate in the study differed systematically from those who participated. However, the primary aims of the current study were to understand sexual orientation disparities in psychological distress, substance use, and their co-occurrence, as well as psychosocial mediators of these disparities, and we consider it unlikely that these aims are substantially influenced by a biased selection of participants by sexual orientation. In support of this assumption, a previous independent population-based public health survey in southern Sweden showed a very similar proportion of sexual minorities as was found in the current study [55, 56].

Despite these limitations, the study also has several strengths, including its use of a large national population-based representative sample that included a measure of sexual orientation alongside measures of stress exposures and behavioral health outcomes. Nationally representative datasets that contain this combined information are rare. Consequently, many studies of sexual orientation health disparities have relied on nonrandom samples, which limits generalizability of findings [57], or have used representative samples to identify sexual orientation disparities in behavioral health outcomes but without measures of potential mediators of those disparities. The present data not only allowed us to establish a robust estimate of the prevalence of co-occurring psychosocial health outcomes in the Swedish population, but also enables a test of potential stress-related mechanisms of these co-occurring disparities as hypothesized by minority stress theory [57]. The results highlight the utility of concurrently addressing co-occurring psychosocial syndemic factors and their stigma-related stress determinants in primary and secondary prevention interventions [58].

Whereas prior research demonstrates that sexual minorities experience significant elevations in adverse psychosocial health outcomes, the present results extend those findings by showing that sexual minorities also experience elevations in the co-occurrence of these outcomes as a function of their exposure to stigma-related stressors. Future research can build on these findings by testing the causal sequence from stress exposure to these co-occurring outcomes and the potential causal influence of these outcomes on each other. Further, given that the social climate surrounding sexual minorities varies widely across world countries [59,60,61], future studies should also explore the extent to which the current findings generalize across countries. Such studies, for instance, might take advantage of the wide variation in social climates surrounding sexual minorities to predict sexual orientation disparities in psychosocial health outcomes and mediators from this variation. In the meantime, this study adds to a growing body of research showing that sexual minorities experience multiple threats to optimal health and points toward future interventions that address the shared sources of these overlapping health threats in social disadvantage.

References

Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ (2010) A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health 100(10):1953–1960. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.174169

Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim HJ, Barkan SE, Muraco A, Hoy-Ellis CP (2013) Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: results from a population-based study. Am J Public Health 103(10):1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301110

Hughes T, Szalacha LA, McNair R (2010) Substance abuse and mental health disparities: comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Soc Sci Med 71(4):824–831

McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ (2009) Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction 104(8):1333–1345

Seil KS, Desai MM, Smith MV (2014) Sexual orientation, adult connectedness, substance use, and mental health outcomes among adolescents: findings from the 2009 New York City Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Inf 104(10):1950–1956

Blosnich JR, Horn K (2011) Associations of discrimination and violence with smoking among emerging adults: differences by gender and sexual orientation. Nicot Tob Res ntr183 13:1284–1295

Blosnich JR, Farmer GW, Lee JG, Silenzio VM, Bowen DJ (2014) Health inequalities among sexual minority adults: evidence from ten US states, 2010. Am J Prev Med 46(4):337–349

Gonzales G, Przedworski J, Henning-Smith C (2016) Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the united states: results from the National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern Med 176(9):1344–1351

Meyer I (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5):674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Bränström R (2017) Minority stress factors as mediators of sexual orientation disparities in mental health treatment: a longitudinal population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 71(5):446–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207943

Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG (2003) Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(1):53–61

Wichstrom L, Hegna K (2003) Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population. J Abnorm Psychol 112(1):144–151

Bränström R, Hatzenbuehler ML, Tinghög P, Pachankis JE (2017) Sexual orientation disparities in diagnosed psychiatric disorder: evidence from a population-based study of siblings. Eur J Epidemiol (resubmission)

Ploderl M, Tremblay P (2015) Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry (Abingdon Engl) 27(5):367–385. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949

Chakraborty A, McManus S, Brugha TS, Bebbington P, King M (2011) Mental health of the non-heterosexual population of England. Br J Psychiatry 198(2):143–148

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, Bukstein OG, Morse JQ (2008) Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 103(4):546–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL (2009) Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction 104(6):974–981

Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Birkett M, Mustanski B (2014) A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors for cigarette smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 54(5):558–564

Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, Friedman MS (2014) Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 43(1):30–39

Bränström R, Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, Link BG (2016) Sexual orientation disparities in preventable disease: a fundamental cause perspective. Am J Public Health 06(6):1109–1115

Pakula B, Shoveller J, Ratner PA, Carpiano R (2016) Prevalence and co-occurrence of heavy drinking and anxiety and mood disorders among gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual Canadians. Am J Public Health 106(6):1042–1048

Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Johnson T (2005) The co-occurrence of depression and alcohol dependence symptoms in a community sample of lesbians. J Lesbian Stud 9(3):7–18

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J (2006) A model of sexual risk behaviors among young gay and bisexual men: longitudinal associations of mental health, substance abuse, sexual abuse, and the coming-out process. AIDS Educ Prev 18(5):444–460

Pachankis JE (2015) A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Arch Sex Behav 44(7):1843–1860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0480-x

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG (2013) Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 103(5):813–821. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301069

Singer M, Clair S (2003) Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q 17(4):423–441

Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Storholm ED, Solomon TM, Bub KL (2013) Measurement model exploring a syndemic in emerging adult gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 17(2):662–673

Halkitis PN, Kapadia F, Bub KL, Barton S, Moreira AD, Stults CB (2015) A longitudinal investigation of syndemic conditions among young gay, bisexual, and other MSM: the P18 cohort study. AIDS Behav 19(6):970–980

Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G (2007) Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med 34(1):37–45

Mustanski B, Andrews R, Herrick A, Stall R, Schnarrs PW (2014) A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. Am J Public Health 104(2):287–294

Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, Mimiaga MJ, Stall R (2010) Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999) 55(Suppl 2):S74

Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, Pollack L, Binson D, Osmond D, Catania JA (2003) Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 93(6):939–942

Hatzenbuehler ML, Jun HJ, Corliss HL, Austin SB (2014) Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Ann Behav Med 47(1):48–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9548-9

Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ (2014) The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med 103:67–75

Hatzenbuehler ML, Wieringa NF, Keyes KM (2011) Community-level determinants of tobacco use disparities in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: results from a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 165(6):527–532

Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K (2011) Discrimination and alcohol-related problems among college students: a prospective examination of mediating effects. Drug Alcohol Depend 115(3):213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.002

Ylioja T, Cochran G, Woodford MR, Renn KA (2016) Frequent experience of LGBQ microaggression on campus associated with smoking among sexual minority college students. Nicot Tob Res ntw305

Bariola E, Lyons A, Leonard W (2016) Gender-specific health implications of minority stress among lesbians and gay men. Aust N Z J Public Health 40(6):506–512

Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE (2013) Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychol Addict Behav 27(3):639

Hughes TL, Szalacha LA, Johnson TP, Kinnison KE, Wilsnack SC, Cho Y (2010) Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addict Behav 35(12):1152–1156

McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ (2010) The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 100(10):1946–1952

Mereish EH, O’Cleirigh C, Bradford JB (2014) Interrelationships between LGBT-based victimization, suicide, and substance use problems in a diverse sample of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol Health Med 19(1):1–13

Lee JH, Gamarel KE, Bryant KJ, Zaller ND, Operario D (2016) Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. LGBT Health 3(4):258–265

Pachankis JE, Westmaas JL, Dougherty LR (2011) The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. J Consult Clin Psychol 79(2):142

Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team (SMART) (2009) Best practices for asking questions about sexual orientation on surveys. The Williams Institutet, California, USA

Sell RL, Wells JA, Wypij D (1995) The prevalence of homosexual behavior and attraction in the United States, the United Kingdom and France: results of national population-based samples. Arch Sex Behav 24(3):235–248

Swedish National Institute of Public Health (2010) The risk drinking project in Sweden. Alcohol Prevention in Primary Health Care and Occupational Health Care, Östersund, Sweden

Aalto AM, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Uutela A, Pirkola S (2012) The beck depression inventory and general health questionnaire as measures of depression in the general population: a validation study using the composite international diagnostic interview as the gold standard. Psychiatry Res 197(1–2):163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.008

Holi MM, Marttunen M, Aalberg V (2003) Comparison of the GHQ-36, the GHQ-12 and the SCL-90 as psychiatric screening instruments in the Finnish population. Nord J Psychiatry 57(3):233–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310001418

Matthews AK, Steffen A, Hughes T, Aranda F, Martin K (2017) Demographic, healthcare, and contextual factors associated with smoking status among sexual minority women. LGBT Health 4(1):17–23

Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Hasin DS (2017) Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend 170:82–92

Bränström R, Pachankis J, Hatzenbuehler M (2015) Sexual orientation based differences in mental health morbidity: age effects in a population-based longitudinal study in Sweden. Eur J Public Heatlh 25(suppl 3) (ckv173-014)

Cochran SD, Grella CE, Mays VM (2012) Do substance use norms and perceived drug availability mediate sexual orientation differences in patterns of substance use? Results from the California quality of life survey II. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73(4):675–685

Green KE, Feinstein BA (2012) Substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: an update on empirical research and implications for treatment. Psychol Addict Behav 26(2):265

Axelsson J, Moden B, Rosvall M, Lindstrom M (2013) Sexual orientation and self-rated health: the role of social capital, offence, threat of violence, and violence. Scand J Public Health 41(5):508–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813476159

Lindstrom M, Axelsson J, Moden B, Rosvall M (2014) Sexual orientation, social capital and daily tobacco smoking: a population-based study. BMC Public Health 14:565. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-565

Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL (2013) Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci 8:521–548

Pachankis JE (2014) Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clin Psychol 21(4):313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12078

Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mirandola M, Weatherburn P, Berg RC, Marcus U, Schmidt AJ (2017) The geography of sexual orientation: structural stigma and sexual attraction, behavior, and identity among men who have sex with men across 38 European countries. Arch Sex Behav 46(5):1491–1502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0819-y

Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Berg RC, Fernandez-Davila P, Mirandola M, Marcus U, Weatherburn P, Schmidt AJ (2017) Anti-LGBT and anti-immigrant structural stigma: an intersectional analysis of sexual minority men’s HIV risk when migrating to or within Europe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000001519

Pachankis JE, Bränström R (2018) Hidden from happiness: structural stigma, sexual orientation concealment, and life satisfaction across 28 countries. J Consult Clin Psychol (in press)

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council [2016-01707] and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (Nr: 2014-0173). The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analyses, interpretation of data, or the reporting of findings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Pachankis and Bränström both participated in the conception, analytic strategies, and writing of the current study. Bränström had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Both authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data, as well as drafting and revising the text, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (No. 2013/2200-31/2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bränström, R., Pachankis, J.E. Sexual orientation disparities in the co-occurrence of substance use and psychological distress: a national population-based study (2008–2015). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53, 403–412 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1491-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1491-4