Abstract

In this study we investigate the lithospheric stresses computed from the gravity and lithospheric structure models. The functional relation between the lithospheric stress tensor and the gravity field parameters is formulated based on solving the boundary-value problem of elasticity in order to determine the propagation of stresses inside the lithosphere, while assuming the horizontal shear stress components (computed at the base of the lithosphere) as lower boundary values for solving this problem. We further suppress the signature of global mantle flow in the stress spectrum by subtracting the long-wavelength harmonics (below the degree of 13). This numerical scheme is applied to compute the normal and shear stress tensor components globally at the Moho interface. The results reveal that most of the lithospheric stresses are accumulated along active convergent tectonic margins of oceanic subductions and along continent-to-continent tectonic plate collisions. These results indicate that, aside from a frictional drag caused by mantle convection, the largest stresses within the lithosphere are induced by subduction slab pull forces on the side of subducted lithosphere, which are coupled by slightly less pronounced stresses (on the side of overriding lithospheric plate) possibly attributed to trench suction. Our results also show the presence of (intra-plate) lithospheric loading stresses along Hawaii islands. The signature of ridge push (along divergent tectonic margins) and basal shear traction resistive forces is not clearly manifested at the investigated stress spectrum (between the degrees from 13 to 180).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Several different theories have been proposed to explain driving forces of plate tectonics. In a pioneering study, Runcorn (1962) was reasoning that the continental drift is a consequence of convection flow in the mantle (see also Runcorn 1980). After a better understanding of tectonic processes as well as the Earth’s inner structure based on the analysis of various geophysical and geodetic data, different hypotheses have been proposed to explain mechanisms of lithospheric plate motions. Some authors suggested that, rather than global mantle flow (e.g., Ricard et al. 1984; Bai et al. 1992), the lithospheric plate boundary and body forces are responsible for the plate motion. They include ridge push (e.g., McKenzie 1968, 1969; Richardson 1992; Ziegler 1992, 1993; Bott 1991a, b, 1993), slab pull (e.g., Forsyth and Uyeda 1975; Chapple and Tullis 1977), trench suction (e.g., Wilson 1993), collisional resistance (e.g., Forsyth and Uyeda 1975), and basal drag (e.g., Wortel and Vlaar 1976; Jacoby 1980; Fleitout 1991; Richardson 1992). These tectonic forces as well as the lithospheric load, volcanism, elasticity of the lithosphere, viscosity of the asthenosphere, and other rheological parameters and geodynamic/geological processes contribute to the overall stress state of the lithosphere. Some authors suggested that the origin of large-scale lithospheric stresses is mainly aligned to a frictional drag due to global mantle flow (e.g., Hager and O’Connell 1981; Steinberger et al. 2001), while others argue that the lithospheric stresses are attributed mainly to the lithospheric plate boundary and body forces (Ricard et al. 1984; Bai et al. 1992; Jurdy and Stefanick 1991).

The first low-degree global gravity models in the 1960s determined from the orbital parameters of early satellite missions, were used in studies of the Earth’s inner structure and processes. In context of stress studies, Kaula (1963) developed a method based on minimizing the strain energy and using the low-degree gravitational and topographic harmonics to estimate the minimum stresses in an elastic Earth. Runcorn (1964, 1967) formulated a functional relation between the stress and the gravity based on solving the Navier–Stokes’ equations for modelling the horizontal shear stresses below the crust, while considering a two-layered model for the Earth so that the upper layer (crust) is floating on the viscous layer (mantle) below. He then used the low-degree spherical harmonics of the Earth’s gravity field to deduce the global horizontal stress pattern, and found a correlation between the convergent and divergent sites established by the plate theory. Liu (1977, 1978, 1979) applied Runcorn’s theory to construct maps of the convection-generated stresses driving the movements of tectonic plates. Liu (1980) also studied the relation between the mantle-convection generated stresses and the intra-plate volcanism. Huang and Fu (1982) and Fu and Huang (1983) extended Runcorn’s definition for the full stress tensor represented by six independent components, while assuming a constant depth of the lithosphere. They solved the boundary-value problem of elasticity according to Love (1944) to model the stress field inside the lithosphere, and used Runcorn’s formulae to define the boundary conditions to solve this problem.

Major theoretical deficiencies of these definitions are related to disregarding mantle viscosity variations and crustal deformations, because lithospheric stresses reflect the rheology and thermal state of the lithosphere as well as driving forces of plate motions. After a rapid expansion of global seismic networks and a development of space techniques for a precise determination of plate motions (such as VLBI, GPS), seismic tomography data and global tectonic plate motion models become preferably used to model tectonic stresses. Among existing studies we could mention earlier works by Richardson et al. (1979), Richardson (1992), and Bai et al. (1992), or more recent studies by Steinberger et al. (2001), Lithgow-Bertelloni and Guynn (2004), and Naliboff et al. (2009, 2012). Furthermore, bore-hole breakouts, hydraulic fracturing, volcanic alignment, seismic focal mechanisms, heat flow on faults, transform fault azimuths, and other in situ stress measurements were also used to investigate and predict the global stress pattern (Zoback and Zoback 1991; Sperner et al. 2003; Heidbach et al. 2007, 2010) and to compile the World Stress Map Database (Zoback 1992; Heidbach et al. 2016).

Even though global seismic networks and locations covered by in situ stress measurements increased steadily over the last few decades, most of them are concentrated in seismically active regions, while large parts of the world are still not yet sufficiently covered by these data. Global gravity models (which have almost global and homogenous coverage) could therefore be used as an alternative source of information to detect the lithospheric stresses. Following this concept, the lithospheric stress determination from gravity data has recently been addressed by Eshagh (2014a, b), Eshagh and Tenzer (2015), Tenzer and Eshagh (2015), Tenzer et al. (2017), and Eshagh (2017). Moreover, gravimetric methods could also be used to investigate the lithospheric stresses of planetary bodies (cf. Tenzer et al. (2015). In aforementioned studies, the horizontal shear stresses computed according to Runcorn’s (1967) theory. Moreover, the two-layered model (used by Runcorn for the crust and the mantle) should correctly be assumed for the solid lithosphere and the viscous asthenosphere, because information about the lithospheric thickness is now available (e.g., Conrad and Lithgow-Bertelloni 2006). In this study, we apply the method developed by Huang and Fu (1982) and Fu and Huang (1983) to evaluate the lithospheric stress tensor globally from the gravity and lithospheric structure models, while assuming a variable lithospheric thickness. We further subtract the long-wavelength signature of global mantle flow in order to enhance the medium-to-higher frequency spectrum of the lithospheric stresses. We then interpret results with respect to tectonic and loading forces. The comparison of the gravimetrically-determined lithospheric stresses with results from seismic tomography and in situ stress measurements is out of the scope of this study.

2 Method

In this section we give a brief summary of the boundary-value problem of elasticity and its solution for finding the functional relation between the lithospheric stress tensor and the gravity field.

2.1 Lithospheric Stress Tensor

To begin with, let us define the stress tensor in its generic form (e.g., Turcotte and Schubert 1982; Stuewe 2007)

where {\(\sigma_{ij}\): i, j = x, y, z} are the elements of stress tensor. For an infinitesimal element of the spherical shell, the diagonal elements represent the normal stress and the off-diagonal elements define the shear stress.

To obtain the lithospheric stress tensor, we solve the partial differential equation of elasticity in the spherical domain for a thin spherical shell (cf. Fu and Huang 1983)

where S denotes the displacement field, \(\nabla^{2}\) is the Laplace operator, \(\nabla\) is the gradient operator, \(\nabla \cdot {\mathbf{S}}\) is the divergence of tensor S, \(\chi = 0.71 \times 10^{12}\) and \(\mu = 0.56 \times 10^{12}\) are the elasticity parameters of the Earth’s lithosphere (cf. Fu and Huang 1990).

To solve the differential equation in Eq. (2), we define the following boundary conditions (cf. Runcorn 1967)

where F denotes the force, D is the lithospheric depth, and R is the Earth’s mean radius. The 3-D position is defined by the geocentric spherical coordinates, with the radius r, co-latitude \(\theta\), and longitude \(\lambda\). The boundary conditions, given in Eqs. (3) and (4), specify that forces in the radial, northward, and eastward directions equal zero at the upper boundary of the lithosphere. At the base of the lithosphere (i.e., the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary), the radial force is zero, while global mantle flow induces the shear stresses defined by the components σ xz and σ yz . According to this formulation, viscosity variations of the asthenosphere are completely disregarded and boundary conditions are defined for an undeformed surface. The gravitational field is then directly related to the horizontal shear stress component, under a number of assumptions which might not realistically represent the actual rheology and crustal deformations (cf. Runcorn 1967; Phillips and Ivins 1979). This over-simplistic model thus assumes that the lithospheric stresses could be detected solely from the gravity data without using any constraining information such as the global lithospheric plate velocity model and the rheological model of lithosphere/asthenosphere (detected from seismic tomography). Nevertheless, this model might be applicable to study the terrestrial stress pattern over regions with an insufficient coverage of seismic data and in situ stress measurements, and stresses of planetary bodies (due to a limited knowledge about the rheology of planetary interiors).

2.2 Shear Stress Components

Runcorn (1967) formulated the expression for computing the shear stress components σ xz and σ yz as follows

where s = R/(R − D), M is the Earth’s total mass (including the atmosphere), and g is the Earth’s (surface) mean gravity. The surface spherical harmonics \(T_{n}\) of the disturbing potential \(T\) (i.e., the difference between the actual and normal gravity potentials) in Eq. (5) are given by

where \(Y_{nm} \left( {\theta ,\lambda } \right)\) are the (fully-normalized) spherical harmonic functions of degree n and order m, and the (fully-normalised) coefficients \(T_{nm}\) of the disturbing potential are obtained from the coefficients of a global gravitational model after subtracting the spherical harmonic coefficients of the normal gravity field.

2.3 Stress Tensor in Terms of Gravity

By analogy with Runcorn’s (1967) solution for the shear stress components in terms of gravity (in Eq. 5), we could find an equivalent solution for all elements of the stress tensor in Eq. (1).

The solution of the differential formula in Eq. (2) with the boundary conditions from Eqs. (3) and (4) yields the displacement field for a spherical shell (cf. Beuthe 2008). Using this displacement field and the elastic theory, the final stress equations are found in terms of the spherical harmonics T n and their partial derivatives. From Fu and Huang (1983), the normal stress components are defined by

and the shear stress components read

where \(r^{\prime}\) is the geocentric radius of an arbitrary point inside the lithosphere. The stress tensor coefficients {\(K_{n}^{i}\): i = 1, 2,…, 5} in Eqs. (7)–(12) are given by

where the parameters \(\alpha_{n}\), \(\bar{\alpha }_{n}\), and \(t\) read

It is worth mentioning that Liu (1983) presented similar formulae for the stress tensor coefficients by assuming that \(\chi = \mu \;\).

2.4 Estimation Model

The stress tensor coefficients {\(K_{n}^{i}\): i = 1, 2,…, 5} in Eqs. (13)–(17) depend on the parameters A n , B n , C n , and D n , which define mechanical properties of the lithosphere. Since these parameters are not defined mathematically, their estimation is carried out by solving the system of observation equations

where the design matrix A, the vector of observations l, and the vector of unknown parameters x are defined by

The force-generating function F in the observation vector l (Eq. 23) was defined by Runcorn (1967) in the following form

Moreover, the design matrix in Eq. (22) is formed by the parameters:

3 Numerical Studies

Theoretical definitions from Sect. 2 were applied here to compute globally the lithospheric stress at the Moho interface. In order to better understand the propagation of stresses through the lithosphere, we first investigated the depth-dependence of stress tensor coefficients.

3.1 Kernel Behaviour

To illustrate the sensitivity of the stress tensor coefficients {\(K_{n}^{i}\): i = 1, 2,…, 5} with changing depth, we adopted a uniform lithospheric model of a constant thickness 100 km. A signal degree of the stress tensor coefficients (at the spectral window between the degrees from 13 to 180) at depths 10, 30, and 70 km (below sea level) are shown in Fig. 1. It is worth mentioning here that this choice of depths closely corresponds with some principal characteristics of global Moho undulations, with a typical thickness of the oceanic crust of about 10 km, an average thickness of the continental crust of about 30–35 km, and the maximum Moho deepening of about 70 km under the Himalayan–Tibetan orogen. Moreover, the long-wavelength contribution below the spherical harmonic degree of 13 was subtracted in order to reduce the stress signature of sub-lithospheric convection pattern (cf. also Liu 1977).

For certain degrees of the stress tensor coefficients {\(K_{n}^{i}\): i = 1, 2,…, 5} defined in Eqs. (13)–(17), the system of observation equations in Eq. (21) becomes singular, because of their spectral behaviour. One example can be given for s = 1. In this case, the design matrix (in Eq. 22) is singular, because the first two rows are identical as well as the last two rows. In fact, the non-singularity of the design matrix holds only for s > 1 (cf. Eq. 22). A detailed inspection also revealed that the degree signal increases unboundedly for n or n − 2, while rapidly decreases for −(n + 1) and −(n + 3). Such spectral behaviour causes that some elements of the design matrix become very large at higher degrees, while others very small. In addition, the diagonal elements, comprising terms \(s^{n}\) and \(s^{n - 2}\), grow unlimitedly with n, thus causing that the design matrix becomes ill-conditioned. For this reason, we used Moore–Penrose’s pseudo-inverse technique (cf. Moore 1920; Bjerhammar 1951; Penrose 1955), instead of applying a regular matrix inversion.

In absolute sense, the stress tensor coefficient \(K_{n}^{1}\) increases up to the degree of about 15–20 (depending on the depth), and then monotonously decreases (cf. Fig. 1). Moreover, the magnitude of \(K_{n}^{1}\) increases (again in absolute sense) when computed at larger depths. For \(K_{n}^{2}\), the situation is opposite. In this case, the signal of \(K_{n}^{2}\) decreases with depth. The coefficients \(K_{n}^{1}\) and \(K_{n}^{2}\) are used to compute the stress tensor component σ zz according to Eq. (9). For the elasticity parameters: \(\chi = 0.71 \times 10^{12}\) and \(\mu = 0.56 \times 10^{12}\), the contribution of the \(K_{n}^{2}\)—term on the right-hand side of Eq. (9) is larger than the corresponding contribution of the \(K_{n}^{1}\)—term. Hence, the stress tensor component σ zz magnifies (in absolute sense) with an increasing depth, as it is clear from the depth-dependent behaviour of \(K_{n}^{2}\) (see Fig. 1).

As also seen in Fig. 1, among the stress tensor coefficients \(K_{n}^{1}\), \(K_{n}^{3}\), and \(K_{n}^{5}\), used in Eqs. (7) and (8), the contribution of \(K_{n}^{5}\) is the smallest. Moreover, the coefficients \(K_{n}^{1}\) and \(K_{n}^{3}\) are negative, and \(K_{n}^{3}\) does not show any significant dependence on depth, but when added to \(K_{n}^{1}\), their combined contribution becomes more depth-sensitive. As seen in Eq. (10), the component σ xy is functionally related only with the coefficient \(K_{n}^{5}\). Since the contribution of \(K_{n}^{5}\) is the smallest, the component σ xy is also the smallest among the stress tensor components. In Eqs. (11) and (12) we observe that the stress tensor components σ xz and σ yz involve the combination \(K_{n}^{4} - K_{n}^{5} + K_{n}^{3}\). Among these coefficients, \(K_{n}^{3}\) has the strongest signal which dominates the total signal of the combination.

3.2 Data Acquisition

The computation of the lithospheric stresses at the Moho interface from the gravity data requires information about the lithospheric thickness and the Moho geometry. In our study, we used the lithospheric-thickness model presented by Conrad and Lithgow-Bertelloni (2006).

They adopted a half-space cooling model (Turcotte and Schubert 1982) according to which the oceanic lithospheric thickness increases proportionally with the square-root of its age. Since they used data of the ocean-floor age from Müller et al. (1997) to compute the oceanic lithospheric thickness; we updated their result based on using more recent data from Müller et al. (2008). Despite some substantial deviations have been documented, especially under oceanic subduction zones (cf. Conrad and Lithgow-Bertelloni 2006), a half-space cooling model provides a reasonable lithospheric-thickness estimate for most of oceanic regions. For the continental lithosphere, they computed the characteristic thickness by following the method of Gung et al. (2003), who employed the maximum depth for which the seismic velocity anomaly, as determined using Ritsema et al. (2004) seismic tomography model S20RTSb, is consistently greater than 2%, while imposing 100 km as the minimum continental and maximum oceanic characteristic thickness.

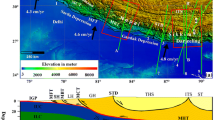

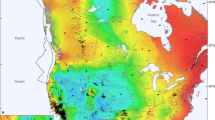

The global map of the lithospheric thickness is shown in Fig. 2. The lithospheric thickness varies from 5 to 270 km. A thin lithosphere along mid-oceanic ridges increases with the ocean-floor age. A much more complex continental lithosphere is characterized by the largest lithospheric deepening under cratons. A significant lithospheric deepening due to the lithospheric subduction is also detected under some orogens (such as Himalaya, Tibet, Central Asian Orogenic Belt, and Andes). It is worth mentioning here that the continental lithosphere may feature even larger variations in thickness, including continental roots that may penetrate to depths as much as 400 km beneath cratonic shields (e.g., Jordan 1975; Ritsema et al. 2004), and are likely cold and highly viscous (e.g., Rudnick et al. 1998).

The Moho depth, taken from the CRUST1.0 seismic crustal model (Laske et al. 2013), is shown in Fig. 3. A maximum Moho deepening to about 70 km is detected under orogens of Himalaya, Tibet, and central Andes. The most pronounced feature in the global Moho pattern is a contrast along continental margins between a thick continental crust and a much thinner oceanic crust.

3.3 Stress Tensor Components

The stress tensor components at the Moho interface were computed according to Eqs. (7)–(12) on a 1 × 1 arc-deg global grid from spherical harmonics of the disturbing potential T n , with a spectral resolution up to the degree of 180. As mentioned above, the long-wavelength harmonics below the degree of 13 were subtracted from the investigated stress spectrum. The spherical harmonics T n were generated from the GOCO-05S coefficients (Mayer-Gürr et al. 2015). The computation was realized by applying the semi-vectorisation algorithm (Eshagh and Abdollahzadeh 2011) in order to take into consideration spatial variations in lithospheric and crustal thickness. The normal and shear stress components are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively, and their statistical summary is given in Table 1.

The most pronounced features in maps of the horizontal normal stress components σ xx and σ yy (Fig. 4a, b) are active convergent tectonic margins of oceanic subductions as well as continent-to-continent tectonic plate collisions. Positive values (of the stress intensity) on the side of subducted lithosphere (oceanic trenches and continental basins) are coupled by negative values on the side of back-arc rifting and orogens. As seen in Fig. 4c, oceanic subductions and continental collisions are again clearly manifested in map of the vertical normal stress component σ zz . In overall, the vertical component has a spatial pattern similar to that seen in horizontal components, but of opposite sign. The maximum shear stresses (see Fig. 5) are again detected along oceanic subductions and continental collisions.

3.4 Total Stress Intensity

We further used the stress tensor components to compute the total stress intensity, individually for the horizontal S hh, vertical S vv, and (mixed) horizontal–vertical S hv components according to the following expressions

The results are plotted in Fig. 6, and their statistical summary is given in Table 2.

Total lithospheric stress intensity: a horizontal S hh, b vertical S vv, c horizontal–vertical S vh, and d stress vectors on the background on the horizontal–vertical stress from spectral degrees 2 to 180. Note that for a better illustration of locations with a maximum stress intensity (for S hh and S vv) we limited the colour scale in such a way that all values exceeding 20 MPa have the same colour

The maximum total stress intensity is detected along oceanic subductions in western Pacific (Kermadec-Tonga, Ryukyu, Mariana, Japan, Kuril, and Aleutian trenches). A slightly less pronounced stress intensity is also seen along oceanic subductions in Atlantic (Puerto Rico and Pacific–Antarctic trenches) and eastern Pacific (Peru–Chile trench). Along continental collisions, large stress intensity is seen between the African and Eurasian plates (Hellenic trench) and between the Indian plate and Tibetan block. The intra-plate stresses are clearly manifested along Hawaii volcanic islands, and along some active thrust fault systems in central Eurasia. We could also see a similar spatial pattern in horizontal and vertical stress intensity, but the vertical stress intensity is about two times larger than the horizontal one (cf. Table 2). It is worth mentioning that the intensity of vertical normal stress is modified by a Moho deepening to about 30% under Himalaya, Tibet, and Andes, because of its dependence on depth (cf. Figure 1), while along oceanic subductions such modification is minor due to a relatively small Moho variations.

4 Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Our results (Fig. 6) agree with findings of Tenzer and Eshagh (2015) and Eshagh and Tenzer (2015) that the lithospheric stresses are mainly manifested along active tectonic margins of oceanic subductions and along continent-to-continent tectonic plate collisions. The maximum stresses are induced by subduction slab pull forces on the side of subducted lithosphere. These stresses are coupled by slightly less pronounced stresses on the side of overriding lithospheric plate of which origin could be explained by trench suction. Our results also showed the presence of (intra-plate) lithospheric loading stresses along Hawaii islands. On the other hand, the stresses due to ridge push force along divergent tectonic plate boundaries are not clearly manifested.

A more detailed inspection of the horizontal normal stresses (Fig. 4a, b) revealed the presence of extensional tectonism of continental basins (Gangetic and Tarim basins). Positive values of the horizontal normal stresses over continental basins are coupled by negative values along Himalaya and the northern Tibet, indicating the compressional tectonism of these orogenic formations. Our results thus confirmed findings from the study conducted in central Eurasia by Tenzer et al. (2017) based on applying Runcorn’s theory. They demonstrated that the convergent pattern of horizontal shear stress vectors agrees with the compressional tectonism of orogens, while their divergent orientation indicates the existence of extensional tectonism of continental basins. Here we also shown that a similar pattern of the normal horizontal stresses is detected along oceanic subductions with positive values on the side of subducted oceanic lithosphere, coupled by negative values on the side of overriding lithospheric plate (i.e., back-arc rifts or orogens).

The horizontal compressional tectonism of orogens (characterised by negative values of the normal horizontal stresses) is responsible for a lithospheric thickening, which should be manifested by an apparent tensional vertical stresses. Our results confirmed this, showing negative values of the normal vertical stresses. In case of continental basins, we detected again the same coupling effect in the horizontal and vertical normal stress components, given by their opposite signs. The same pattern was also found for oceanic subductions and back-arc rifts.

References

Bai, W., Vigny, C., Ricard, Y., & Froidevaux, C. (1992). On the origin of deviatoric stresses in the lithosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 11729–11737.

Beuthe, M. (2008). Thin elastic shells with variable thickness for lithospheric flexure of one-plate planet. Geophysical Journal International, 172, 817–841.

Bjerhammar, A. (1951). Application of calculus of matrices to method of least squares; with special references to geodetic calculations. Transactions of the Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, 49, 86.

Bott, M. H. P. (1991a). Ridge push and associated plate interior stress in normal and hot spot regions. Tectonophyics, 200, 17–32.

Bott, M. H. P. (1991b). Sublithospheric loading and plate-boundary forces. In R. B. Whitmarsh, M. H. P. Bott, J. B. Fairhead, & N. J. Kusznir (Eds.), Tectonic stress in the lithosphere (pp. 83–93). London: Philosoph. Trans. Royal Soc.

Bott, M. H. P. (1993). Modeling the plate-driving mechanism. Journal of the Geological Society, 150, 941–951.

Chapple, W. M., & Tullis, T. E. (1977). Evaluation of the forces that drive the plates. Journal of Geophysical Research, 82, 1967–1984.

Conrad, C. P., & Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. (2006). Influence of continental roots and asthenosphere on plate-mantle coupling. Geophysical Research Letters, 33, L05312.

Eshagh, M. (2014a). From satellite gradiometry data to subcrustal stress due to mantle convection. Pure and Applied Geophsyics, 171, 2391–2406.

Eshagh, M. (2014b). Determination of Moho discontinuity from satellite gradiometry data: linear approach. GRIB., 1(2), 1–13.

Eshagh, M. (2017). Local recovery of lithospheric stress tensor from GOCE gravitational tensor. Geophysical Journal International, 209, 317–333.

Eshagh, M., & Abdollahzadeh, M. (2011). Software for generating gravity gradients using a geopotential model based on irregular semi-vectorization algorithm. Computers and Geosciences, 32, 152–160.

Eshagh, M., & Tenzer, R. (2015). Sub-crustal stress determined using gravity and crust structure models. Computational Geoscience, 19, 115–125.

Fleitout, L. (1991). The sources of lithospheric tectonic stresses. In R. B. Whitmarsh, M. H. P. Bott, J. B. Fairhead, & N. J. Kusznir (Eds.), Tectonic stress in the lithosphere (pp. 73–81). London: Philosoph. Trans. Royal Soc.

Forsyth, D., & Uyeda, S. (1975). On the relative importance of the driving forces of plate motion. Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 43, 63–200.

Fu, R., & Huang, P. (1983). The global stress field in the lithosphere obtained from satellite gravitational harmonics. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interior, 31, 269–276.

Fu, R., & Huang, J. (1990). Global stress pattern constrained on deep mantle flow and tectonic features. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interior, 60, 314–323.

Gung, Y., Panning, M., & Romanowicz, B. (2003). Global anisotropy and the of continents. Nature, 422, 707–711.

Hager, B. H., & O’Connell, R. J. (1981). A simple global model of plate dynamics and mantle convection. Journal of Geophysical Research, 86(B6), 4843–4867.

Heidbach, O., Rajabi, M., Reiter, K., Ziegler, M. & the WSM Team. (2016). World Stress Map Database Release 2016, GFZ Data Services.

Heidbach, O., Reinecker, J., Tingay, M., Müller, B., Sperner, B., Fuchs, K., & Wenzel, F. (2007). Plate boundary forces are not enough: Second- and third-order stress patterns highlighted in the World Stress Map database, Tectonics, 26.

Heidbach, O., Tingay, M., Barth, A., Reinecker, J., Kurfeß, D., & Müller, B. (2010). Global crustal stress pattern based on the World Stress Map database release 2008. Tectonophys, 482, 3–15.

Huang, P., & Fu, R. (1982). The mantle convection pattern and force sources mechanism of recent tectonic movements in China. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interior, 28, 261–268.

Jacoby, W. R. (1980). Plate sliding and sinking in mantle convection and the driving mechanism. In P. A. Davis & F. R. S. Runcorn (Eds.), Mechanisms of continental drift and plate tectonics (pp. 159–172). New York: Academic Press.

Jordan, T. H. (1975). The continental tectosphere. Reviews of Geophysics and Space Physics, 13, 1–2.

Jurdy, D. M., & Stefanick, M. (1991). The forces driving the plates: constraints from kinematics and stress observations. In R. B. Whitmarsh, M. H. P. Bott, J. B. Fairhead, & N. J. Kusznir (Eds.), Tectonic stress in the lithosphere (pp. 127–139). London: Philosoph. Trans. Royal Society.

Kaula, W. M. (1963). Elastic models of the mantle corresponding to variations in the external gravity field. Journal of Geophysical Research, 68(17), 4967–4978.

Laske, G., Masters, G., Ma, Z., & Pasyanos, M. E. (2013). Update on CRUST1.0—a 1-degree global model of Earth’s crust. Geophysical Research Abstracts 15 (Abstract EGU2013-2658).

Lithgow-Bertelloni, C., & Guynn, J. H. (2004). Origin of the lithospheric stress field. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109, B01408.

Liu, H. S. (1977). Convection pattern and stress system under the African plate. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 15, 60–68.

Liu, H. S. (1978). Mantle convection pattern and subcrustal stress under Asia. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 16, 247–256.

Liu, H. S. (1979). Convection-generated stress concentration and seismogenic models of the Tangshan Earthquake. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 19, 307–318.

Liu, H. S. (1980). Convection generated stress field and intra-plate volcanism. Tectonophysics, 65, 225–244.

Liu, H. S. (1983). A dynamical basis for crustal deformation and seismotectonic block movements in central Europe. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interior, 32, 146–159.

Love, A. E. H. (1944). A treatise on the mathematical theory of elasticity (p. 249). New York: Dover Publication.

Mayer-Gürr, T., Pail, R., Gruber, T., Fecher, T., Rexer, M., Schuh, W.-D., Kusche, J., Brockmann, J.-M., Rieser, D., Zehentner, N., Kvas A., Klinger, B., Baur, O., Höck, E., Krauss, S., Jäggi, A., 2015. The combined satellite gravity field model GOCO05 s. Presentation at EGU 2015, Vienna, April 2015.

McKenzie, D. P. (1968). The influence of the boundary conditions and rotation on convection in the Earth’s mantle. Geophysical Journal, 15, 457–500.

McKenzie, D. P. (1969). Speculations on the consequences and causes of plate motions. Geophysical Journal, 18, 1–32.

Moore, E. H. (1920). On the reciprocal of the general algebraic matrix. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 26(9), 394–395.

Müller, R. D., Roest, W. R., Royer, J.-Y., Gahagan, L. M., & Sclater, J. G. (1997). Digital isochrons of the world’s ocean floor. Journal of Geophysical Research, 102, 3211–3214.

Müller, R. D., Sdrolias, M., Gaina, C., & Roest, W. R. (2008). Age, spreading rates and spreading symmetry of the world’s ocean crust. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 9, Q04006.

Naliboff, J. B., Conrad, C. P., & Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. (2009). Modification of the lithospheric stress field by lateral variations in plate-mantle coupling. Geophysical Research Letters, 36, L22307.

Naliboff, J. B., Lithgow-Bertelloni, C., Ruff, L. J., & de Koker, N. (2012). The effects of lithospheric thickness and density structure on Earth’s stress field. Geophysical Journal International, 188(1), 1–17.

Penrose, R. (1955). A generalized inverse for matrices. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 51, 406–413.

Phillips, R. J., & Ivins, E. R. (1979). Geophysical observations pertaining to solid-state convection in the terrestrial planets. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 19(2), 107–148.

Ricard, Y., Fleitout, L., & Froidevaux, C. (1984). Geoid heights and lithospheric stresses for a dynamic Earth. Annales Geophysicae, 2(3), 267–286.

Richardson, R. M. (1992). Ridge forces, absolute plate motions, and the intraplate stress field. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 11739–11748.

Richardson, R. M., Solomon, S. C., & Sleep, N. H. (1979). Tectonic stress in the plates. Reviews of Geophysics, 17(5), 981–1019.

Ritsema, J., van Heijst, H. J., & Woodhouse, J. H. (2004). Global transition zone tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research, 109, B02302.

Rudnick, L. R., McDonough, W. F., & O’Connell, R. J. (1998). Thermal structure, thickness and composition of continental lithosphere. Chemical Geology, 145(3–4), 395–411.

Runcorn, S. K. (1962). Convection currents in the Earth’s mantle. Nature, 195, 1248–1249.

Runcorn, S. K. (1964). Satellite gravity measurements and laminar viscous flow model of the Earth mantle. Journal of Geophysical Research, 69(20), 4389–4394.

Runcorn, S. K. (1967). Flow in the mantle inferred from the low degree harmonics of the geopotential. Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 14, 375–384.

Runcorn, S. K. (1980). Mechanism of plate tectonics: mantle convection currents, plumes, gravity sliding or expansion? Tectonophysics, 63, 297–307.

Sperner, B., Müller, B., Heidbach, O., Delvaux, D., Reinecker, J., & Fuchs, K. (2003). Tectonic stress in the Earth’s crust: advances in the World Stress Map project. In D. A. Nieuwland (Ed.), New insights in structural interpretation and modelling (Vol. 212, pp. 101–116). London: Geol. Soc. Spec. Pub. (Special Publication).

Steinberger, B., Schmeling, H., & Marquart, G. (2001). Large-scale lithospheric stress field and topography induced by global mantle circulation. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 186, 75–91.

Stuewe, K. (2007). Geodynamics of the lithosphere (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer.

Tenzer, R., & Eshagh, M. (2015). Subduction generated sub-crustal stress in Taiwan. Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, 26(3), 261–268.

Tenzer, R., Eshagh, M., & Jin, S. (2015). Martian sub-crustal stress from gravity and topographic models. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 425, 84–92.

Tenzer, R., Eshagh, M., & Shen, W. (2017). The sub-crustal stress estimation in central Eurasia from gravity, terrain and crustal structure models. Geoscience Journal, 21(1), 47–54.

Turcotte, D. L., & Schubert, G. (1982). Geodynamics: Applications of continuum physics to geological problems. New York: Wiley.

Wilson, M. (1993). Plate-moving mechanisms: constraints and controversies. Journal of the Geological Society, 150, 923–926.

Wortel, M. J. R., & Vlaar, N. J. (1976). Lithospheric aging, instability and subduction. Tectonophysics, 32, 331–351.

Ziegler, P. A. (1992). Plate tectonics, plate moving mechanisms and rifting. Tectonophysics, 215, 9–34.

Ziegler, P. A. (1993). Plate-moving mechanisms: their relative importance. Journal of the Geological Society, 150, 927–940.

Zoback, M. L. (1992). First and second order patterns of stress in the lithosphere: The World Stress Map Project. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 11703–11728.

Zoback, M., & Zoback, M. L. (1991). Tectonic stress field of North America and relative plate motions. In D. B. Slemmons, E. R. Engdahl, M. D. Zoback, & D. D. Blackwell (Eds.), Neotectonics of North America (pp. 339–366). Boulder: Geological Society of America.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the editor, Dr. Erik Ivins from NASA, his reviewing board for their constructive comments to the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Eshagh, M., Tenzer, R. Lithospheric Stress Tensor from Gravity and Lithospheric Structure Models. Pure Appl. Geophys. 174, 2677–2688 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1538-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1538-6