Abstract

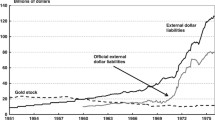

In the postcrisis period, some foreign policymakers accused the Federal Reserve of engaging in “currency wars” and inadvertently creating “financial spillovers,” arguing that these were especially consequential given the dominant role of the U.S. dollar in international trade and finance. This lecture analyzes these critiques, and argues: (1) little support exists, either theoretical or empirical, for the currency wars claim; (2) the United States and its trading partners should use nonmonetary tools for dealing with spillovers; and (3) the benefits of the dollar standard to the United States and the world are considerably more symmetric than in the Bretton Woods era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Raghuram Rajan, governor of the Reserve Bank of India and former chief economist of the IMF, has been an important voice on this issue. See Shefali Anand and Jon Hilsenrath, 2013, “India’s Central Banker Lobbies Fed,” Wall Street Journal, October 13.

The phrase was coined in 1965 by French finance minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to describe the gains to the United States from the central role of the dollar in the Bretton Woods system.

For the BIS’s own overview of the meetings, see www.bis.org/about/bimonthly_meetings.htm.

The joint statement is here: www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081008a.htm

For an overview of the currency swap program, see www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_liquidityswaps.htm

Competitive depreciation became a contentious issue during the Great Depression (Bernanke, 2013). At the time, some economists argued that the depreciations associated with countries’ abandoning of the gold standard were “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies (Robinson, 1947). Since the seminal work of Eichengreen and Sachs (1985), however, the profession has come to recognize that the primary effect of the collapse of the gold standard was to permit reflationary policies and higher national incomes, which had wide benefits.

The absence of significant gains in the U.S. trade balance or depreciation of the dollar in part reflects countervailing efforts by U.S. trading partners to weaken their own currencies. However, as discussed in the text, the ability of trading partners to offset the effects of U.S. monetary policy on their own economies mitigates potential spillover effects. Moreover, to the extent that U.S. trading partners responded to Federal Reserve easing with easing policies of their own, the net effect of the U.S. policy initiatives was to stimulate a global reflation of aggregate demand rather than to set off a competition for export markets. The situation bears some analogy to the 1930s, when the staggered abandonment of the gold standard resulted in a stronger global economy with little net change in trade positions; see footnote 6.

There are other motivations for “fear of floating” (Calvo and Reinhart, 2002) as well, such as concerns about the dollar liabilities of emerging-market banks and firms. I return to this issue later.

The second term on the right side of Equation (1) is the current level of the exchange rate. In general, expected depreciation depends also on the expected future exchange rate. However, we have assumed that the future price level is given. The additional assumption that future output is expected to be at its steady-state level pins down the future real exchange rate at the level consistent with the steady state. These conditions determine the expected future exchange rate, allowing it to be ignored for the purposes of this analysis. Alternatively, if exchange rates have a temporary component, then a “high” current exchange rate implies that depreciation is expected, and vice versa.

As alternative formulation, consistent with EME targeting a specific level of the exchange rate, would be to include the square of the exchange rate in the loss function in lieu of exports. With that loss function, EME policymakers would equally dislike policy easing or tightening abroad. In the case analyzed here, they particularly dislike foreign policy easing.

A similar incentive arises in the time consistency literature (Barro and Gordon, 1983), except that in that case policymakers have an incentive to try to engineer “surprise” inflation. As in that literature, policymakers’ incentives to overheat the economy in the short run presumably would result in an upward inflation bias in the longer term.

From Equation (1), if the exchange rate moves little, then the domestic interest rate must fall by nearly as much as the U.S. interest rate.

The short-run effects on EME output of a change in U.S. monetary policy will depend also on how the two channels of effect manifest over time. One might guess that the expenditure-switching effect will be felt more quickly, because Federal Reserve policy changes affect the exchange rate nearly instantaneously. That conclusion is not necessarily right, though, because the effects of the exchange rate on exports and aggregate demand themselves take time to appear.

I am assuming that EME fiscal policy cannot be used flexibly for macroeconomic stabilization purposes. If that assumption is wrong, then EME has enough tools to manage both domestic output and its real exchange rate.

These effects are related but not identical to the exchange-rate and foreign output terms in the EME export equation, Equation (3). As usually interpreted in the empirical literature, these effects include the endogenous responses of trading partners, whereas the terms in Equation (3) are partial-equilibrium effects.

I thank Steve Kamin and Chris Erceg of the Board of Governors staff for conversations and additional details. Note that the financial spillover effect discussed here is not the same as the financial stability spillovers that are the subject of the next section.

Ammer and others (2016) note that their results are consistent with the traditional literature on trade elasticities; see for example Hooper, Johnson, and Marquez (2000).

Interestingly, these authors found the spillover effect to be smaller (though of the same sign) in the 2000s than in the 1990s.

See the June 19, 2013, press conference transcript, p. 5: www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20130619.pdf

In contrast to the currency war episode, these complaints were about a U.S. policy tightening. Financial stability concerns have been voiced about any shift in U.S. monetary policy, whether toward tightness or ease.

See also Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2015) and Passari and Rey (2015).

It is sometimes asserted that unconventional monetary policies, like asset purchases, have different spillover effects than conventional policies. The literature doesn’t provide much clarity on this proposition. For example, Chen, Mancini-Griffoli, and Sahay (2014) find that unconventional monetary policy had relatively stronger effects, while Bowman, Londono, and Sapriza (2014) and Rogers, Scotti, and Wright (2014) don’t find a significant difference between the effects of conventional and unconventional monetary policies.

The estimated lags are sufficiently long that it may be better to interpret this research as reflecting long-run buildups of financial risk rather than short-run swings in risk appetite. For example, Rey (2013) finds that a decline in the fed funds rate is followed by a rise in gross credit flows and European bank leverage, but only after about 12 quarters and 15 quarters respectively (p. 306). Bruno and Shin (2013) similarly find that a change in the funds rate affects leverage at U.S. broker-dealers in about 10 quarters. The models of Shin and coauthors, discussed below, likewise seem to apply most directly to longer-term buildups of risk.

I am indebted to Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas for suggesting this formulation and for several of the points made here.

If i is interpreted as a shadow price of credit, rather than as the market interest rate, Equation (1′) might also reflect variation in credit terms or credit availability.

The literature on the “risk-taking channel” of monetary policy finds that monetary policy actions work in part by affecting investors’ risk preferences, although I am not aware of much theoretical analysis of the channel (Bruno and Shin, 2015). There is some connection to the financial accelerator/credit channel to which I contributed many years ago. See for example, Bernanke, Gertler, and Gilchrist (1999). In that framework, cuts in interest rates increase the net worth of borrowers and thus make them more creditworthy.

It is true that changes in the risk premium δ may affect broad financial conditions (for example, leverage and risk taking) in U.S. trading partners and thus pose policy challenges in the longer run. But the existence of a time-varying risk premium, or of a risk-taking channel of U.S. monetary policy, is neither necessary nor sufficient for that conclusion to hold. It’s not necessary, in that (at least according to some observers) the level of the nominal interest rate itself may affect leverage and risk-taking, even if risk premiums don’t vary. It’s not sufficient, since variation in risk premiums may be benign in some instances, as illustrated by my stylized example earlier in this section.

Stress testing is also required by the Dodd-Frank reforms.

A recent (September 2015) IMF staff study, “Monetary Policy and Financial Stability,” reached a similar conclusion. See www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2015/082815a.pdf.

To avoid persistent imbalances in trade or capital flows, the system envisioned occasional adjustments of parities.

For example, Rogers, Scotti, and Wright (2014) find that a U.S. monetary easing that lowers the 10-year Treasury yield by 25 basis points reduces the yields on the U.K. gilt, the German 10-year bund, and the Japanese 10-year JGB by 13, 9, and 5 basis points, respectively.

References

Adrian, T. and H. S. Shin, 2014, “Procyclical Leverage and Value-at-Risk,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 373–403.

Ahmed, S., B. Coulibaly and A. Zlate, 2015, “International Financial Spillovers to Emerging Market Economies: How Important Are Economic Fundamentals?” International Finance Discussion Papers No. 1135.

Ahmed, S. and A. Zlate, 2014, “Capital Flows to Emerging Market Economies: A Brave New World?,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 48, No. PB, pp. 221–48.

Aizenman, J., MD Chinn and H. Ito, 2015, “Monetary Policy Spillovers and the Trilemma in the New Normal: Periphery Country Sensitivity to Core Country Conditions,” NBER Working Paper No. 21128.

Ajello, T., T. Laubach, D. López-Salido and T. Nakata, 2015, “Financial Stability and Optimal Interest-Rate Policy,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Working Paper.

Ammer, J., M. De Pooter, C. Erceg and S. Kamin, 2016, “International Spillovers of Monetary Policy,” International Finance Discussion Papers (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve) Published as an IFDP Note.

Barro, R. J. and D. B. Gordon, 1983, “Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 101–21.

Bernanke, B., 2002, “Asset Price ‘Bubbles’ and Monetary Policy,” Lecture presented to the National Association for Business Economics, New York.

Bernanke, B., 2013, “Monetary Policy and the Global Economy,” Lecture at the London School of Economics, London.

Bernanke, B., M. Gertler and S. Gilchrist, 1999, “The Financial Accelerator in a Quantitative Business Cycle Framework,” in Handbook of Macroeconomics, Handbooks in Economics, Vol. 1C Vol. 15 ed. by J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford (Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier B.V.), pp. 1341–93.

Bowman, D., J.M. Londono and H. Sapriza, 2014, “U.S. Unconventional Monetary Policy and Transmission to Emerging Market Economies,” International Finance Discussion Papers No. 1109 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve).

Bruno, V. and H. S. Shin, 2013, “Capital Flows, Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity,” NBER Working Paper No. 19038.

Bruno, V. and H. S. Shin, 2015, “Capital Flows and the Risk-Taking Channel of Monetary Policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 71, No. C, pp. 119–32.

Calvo, G. and C. Reinhart, 2002, “Fear of Floating,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117 (May), pp. 379–408.

Chen, Q., A. Filardo, D. He and F. Zhu, 2015, “Financial Crisis, U.S. Unconventional Monetary Policy and International Spillovers,” IMF Working Paper No. 15/85.

Chen, J., T. Mancini-Griffoli and R. Sahay, 2014, “Spillovers from United States Monetary Policy on Emerging Markets: Different This Time?” IMF Working Paper No. 14/240.

Chow, J. S., F. Jaumotte, S.G. Park and Y.S. Zhang, 2015, “Spillovers from Dollar Appreciation,” IMF Policy Discussion Paper No. 15/02.

Eichengreen, B. and J. Sachs, 1985, “Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 925–46.

Fischer, S., 2015a, “Macroprudential Policy in the U.S. Economy,” Remarks at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, MA.

Fischer, S., 2015b, “The Transmission of Exchange Rate Changes to Output and Inflation,” Remarks at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, Washington, DC.

Fratzscher, M., 2012, “Capital Flows, Push versus Pull Factors and the Global Financial Crisis,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 341–56.

Fukuda, Y., Y. Kimura, N. Sudo and H. Ugai, 2013, “Cross-country Transmission Effect of the U.S. Monetary Shock under Global Integration,” Bank of Japan Working Paper No. 13-E-16.

Geanakoplos, J., 2010, “Solving the Present Crisis and Managing the Leverage Cycle,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 101–31.

Georgiadis, G., 2015, “Determinants of Global Spillovers from U.S. Monetary Policy,” ECB Working Paper No. 1854.

Ghosh, A.R., J.D. Ostry and M.S. Qureshi, 2015, “Exchange Rate Management and Crisis Susceptibility: A Reassessment,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 238–76.

Gourinchas, P., N. Govillot and H. Rey, 2010, “Exorbitant Privilege and Exorbitant Duty,” UC Berkeley Working Paper.

Hooper, P., K. Johnson and J. Marquez, 2000, Trade Elasticities for the G7 Countries, Princeton Studies in International Economics, No. 87, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

Jorda, O., M. Schularick and A.M. Taylor, 2015, “Interest Rates and House Prices: Pill or Poison?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letters No. 2015-25.

Kamin, S., 2015, “Cross-Border Spillovers from Monetary Policy,” presentation at the Peterson Institute of International Economics, Washington, DC Based on joint research with John Ammer, Christopher Erceg, and Michel De Pooter.

McKinnon, R. I., 1993, “The Rules of the Game: International Money in Historical Perspective,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 1–44.

Miranda-Agrippino, S. and H. Rey, 2012, “World Asset Markets and Global Liquidity,” presentation at the BIS-ECB Conference, London Business School, London.

Miranda-Agrippino, S. and H. Rey, 2015, “World Asset Markets and the Global Financial Cycle,” NBER Working Paper No. 21722.

Mishra, P., K. Moriyama, P. P. N’Diaye and L. Nguyen, 2014, “Impact of Fed Tapering Announcements on Emerging Markets,” IMF Working Paper No. 14/109.

Obstfeld, M., 2010, “Expanding Gross Asset Positions and the International Monetary System,” Remarks made to the Jackson Hole Conference of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Passari, E. and H. Rey, 2015, “Financial Flows and the International Monetary System,” Economic Journal, Vol. 125, No. 584, pp. 675–98. (Sargan Lecture, Royal Economic Society, 2014).

Prasad, E. S., 2014, The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press).

Rogers, J., C. Scotti and J. Wright, 2014, “Evaluating Asset-Market Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy: A Multi-Country Review,” Economic Policy, Vol. 29 October, pp. 749–99.

Rey, H., 2013, “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence,” Jackson Hole Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pp. 285–333.

Rey, H., 2014, “International Channels of Transmission of Monetary Policy and the Mundellian Trilemma,” Mundell-Fleming Lecture, International Monetary Fund.

Robinson, J., Ed., 1947, “Beggar-My-Neighbor Remedies for Unemployment,” in Essays in the Theory of Employment (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), 2nd ed. pp. 156–70.

Svensson, L.E.O., 2014, “Inflation Targeting and “Leaning Against the Wind,” International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 10 (June), pp. 103–14.

Wheatley, J. and P. Graham, 2010, “Brazil in ‘Currency War’ Alert,” Financial Times, September 27.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.