Abstract

The Chernobyl nuclear accident of 1986 had deleterious health consequences for the population of Belarus, especially for those who were children at the time of the disaster. Using the 2003–2008 waves of the Belarusian Household Survey of Income and Expenditure (BHSIE), we estimate the effect of radiation exposure on the health, education, and labor market outcomes among cohorts and areas affected by the accident, utilizing the nuclear accident as a natural experiment. We find that young individuals who came from the most contaminated areas had worse health, were less likely to hold university degrees, were less likely to be employed, and had lower wages compared to those who were older at the time of the accident and who came from less contaminated areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

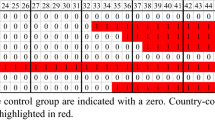

Notes

See, for example, the discussion of the safety of using the contaminated land for agriculture in Belarus: http://lenta.ru/articles/2010/07/22/chernobyl/, accessed on 05.25.2011.

Lehmann and Wadsworth (2009) also looked at the differences in irradiation by age at exposure. However, their analysis looked at the differences at much older ages, and their treatment group was comprised of children under age 13 at the time of the Chernobyl accident.

Because many organs and tissues were exposed by the Chernobyl accident, the concept of effective dose, which characterizes the overall health risk that is due to any combination of radiation, has been commonly used. The effective dose accounts for both absorbed energy and type of radiation and for susceptibility of various organs and tissues to developing a severe radiation-induced cancer or genetic effect. For gamma radiation, the unit of effective dose is the sievert (Sy). (One Gy corresponds to one Sv.) One Sy is a comparatively large dose, so the millisievert or mSv (one one-thousandth of a Sv) is commonly used to describe normal exposures. Annual natural background doses of humans worldwide were estimated to average 2.4 mSv, with a typical range of 1–10 mSv (IAEA 2005).

The rural population of Belarus consumed locally produced milk, and the urban population consumed milk from the numerous local milk factories that used primarily local milk for their production (Kruk 2004).

Hypothyroidism is the result of an underactive thyroid gland that cannot make enough thyroid hormone to keep the body running normally. When thyroid hormone levels are too low, the body’s cells cannot get enough thyroid hormone, and the body’s processes start slowing down. As the metabolism slows, the patient tires easily, becomes forgetful and depressed, and gains weight (Source: American Thyroid Association, http://www.thyroid.org/patients/patient_brochures/childhood.html, accessed on 05.25.2011).

This choice assumes that entry into the labor market entry starts at age 16. While most people at this age are continuing their secondary education, some choose to join the labor force.

We also estimated probit regressions for the binary variables “hospitalized,” “not good health,” “university,” and “employed” and obtained similar results. In order to address endogenous selection into employment, we estimated the wage equation using the Heckman (1979) selection model, where the selection equation included the “not good health” dummy variable in addition to all of the main regression equation variables.

There is also a significant association between the dummy variable “influenced by Chernobyl” (=1 if a person reported being seriously or partially influenced by Chernobyl and zero otherwise) and all health measures in the years 1999–2002 (results not shown). This association gives further support to the hypothesis that the reported health problems were related to Chernobyl. Unfortunately, the survey does not elaborate on exactly how the person was influenced by Chernobyl, and this variable is not available in BHSIE after 2002.

Education variables were not included in the wage regression because they constitute “bad controls,” since they are “outcome variables in the notional experiment at hand” (Angrist and Pischke, 2009). In our case, since all of the individuals are under age 30 and many are still enrolled in secondary education or college, including education variables as controls could introduce selection bias. Furthermore, we are interested in the reduced effect of Chernobyl on earnings, including the part of this effect that works through education.

Notably, a May 1st parade was held as usual in Kiev, right after the catastrophe on April 26, 1986, only 90 km (about 56 miles) away from the burning power plant. Medvedev (1990) documented the lack of information and slow response after the catastrophe, pointing out, for example, that “the population of Pripyat was not warned about the accident, nor were the civil defense headquarters informed. Since the civil defense staff had no information about the situation, they took no measures. As a result, the usual rhythm of life on Saturday proceeded …. The evacuation began only 36 h later and was conducted according to a newly worked-out plan.”

The government of Belarus created special privileges for applicants to secondary professional and higher educational institutions who were from the contaminated regions. For example, Law #9-3 of January 6, 2009, “on social protection of citizens who suffered from the Chernobyl and other radioactive disasters” (article 18 clause 7, article 21 clause 1.3, article 22 clause 1.3, article 23 clause 1.2) provides that people who participated in the liquidation of the consequences of the Chernobyl accident or who lived in the contaminated regions are entitled to preferential rights to obtain secondary, specialized, or higher education.

References

Almond D (2006) Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 U.S. population. J Polit Econ 14(4):672–712

Almond D, Edlund L, Palme M (2009) Chernobyl’s subclinical legacy: prenatal exposure to radioactive fallout and school outcomes in Sweden. Q J Econ 124(4):1729–1772

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, 2009. 392 p

Balonov MI (2007) The Chernobyl Forum: major findings and recommendations. J Environ Radioact 96(1–3):6–12

Bespalchuk PI, Demidchik YE, Demidchik EP, Gedrevich ZE, Dubovskaya AP, Saenko VA, Yamashita S (2007) Thyroid cancer in Belarus after Chernobyl. International Congress Series, No. 1299, pp 27-31

Bleakley HC (2007) Disease and development: evidence from Hookworm Eradication in the American South. Q J Econ 122(1):73–117

Case A, Lubotsky D, Paxson C (2002) Economic status and health in childhood: the origins of the gradient. Am Econ Rev 92(5):1308–1334

Case A, Fertig A, Paxson C (2005) The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. J Health Econ 24:365–389

Farahati J, Demidchik EP, Biko J, Reiners C (2000) Inverse association between age at the time of radiation exposure and extent of disease in cases of radiation-induced childhood thyroid carcinoma in Belarus. Cancer 88(6):1470–1476

Fletcher JM, Lehrer SF (2008) Using genetic lotteries within families to examine the causal impact of poor health on academic achievement. Yale University working paper

Goldsmith JR, Grossman CM, Morton WE, Nussbaum RH, Kordysh EA, Quastel MR, Sobel RB, Nussbaum FD (1999) Juvenile hypothyroidism among two populations exposed to radioiodine. Environ Health Perspect 107(4):303–308

Grossman M, Kaestner R (1997) Effects of education on health. In: Behrman JR, Stacey N (eds) The social benefits of education. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Heckman J (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–61

IAEA (2005) Chernobyl Forum, 2003–2005 (online). http://www-ns.iaea.org/meetings/rw-summaries/chernobyl_forum.htm. Chernobyl Forum, 2003–2005

Kolominsky Y, Igumnov S, Drozdovitch V (1999) The psychological development of children from Belarus exposed in the prenatal period to radiation from the Chernobyl atomic power plant. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 40(2):299–305

Kremer M, Miguel E (2004) Worms: identifying impacts on education and health in the presence of treatment externalities. Econometrica 72:159–217

Kruk JE, Pröhl G, Kenigsberg JI (2004) A radioecological model for thyroid dose reconstruction of the Belarus population following the Chernobyl accident. Radiat Environ Biophys 43(2):101–110

Lehmann H, Wadsworth J (2009) The impact of chernobyl on health and labour market performance in the Ukraine. ESCIRRU Working Paper, No 12, DIW Berlin, German Institute for Economic Research

Loganovskaja TN, Loganovsky KN (1999) EEG, cognitive and psychopathological abnormalities in children irradiated in utero. Int J Psychophysiol 34:213–224

Maccini S, Yang D (2009) Under the weather: health, schooling, and economic consequences of early-life rainfall. Am Econ Rev 99(3)

Medvedev AZ (1990) The legacy of chernobyl. Norton, New York, xiv, 352 pp., illus

Meng X, Qian N (2006) The long run health and economic consequences of famine on survivors: evidence from China’s great famine. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2471

Nyahu AI, Loganovsky KN, Loganovskaja TK (1998) Psychophysiologic aftereffects of prenatal irradiation. Int J Psychophysiol 30:303–311

Ostroumova E, Brenner A, Oliynyk V, McConnell R, Robbins J, Terekhova G, Zablotska L, Likhtarev I, Bouville A, Shpak V, Markov V, Masnyk I, Ron E, Tronko M, Hatch M (2009) Subclinical hypothyroidism after radioiodine exposure: Ukrainian-American cohort study of thyroid cancer and other thyroid diseases after the Chornobyl accident (1998–2000). Environ Health Perspect 117(5):745–750

Pacini F, Vorontsova T, Molinaro E, Kuchinskaya E, Agate L, Shavrova E, Astachova L, Chiovato L, Pinchera A (1998) Prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in children and adolescents from Belarus exposed to the Chernobyl radioactive fallout. Lancet 352(9130):763–766

Pastore F, Verashchagina A (2007) When does transition increase the gender wage gap? An application to Belarus. IZA Discussion Paper No. 2796

Quastel MR, Goldsmith JR, Mirkin L, Poljak S, Barki Y, Levy J, Gorodischer R (1997) Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels in children from Chernobyl. Environ Health Perspect 105(suppl 6):1497–1498

Reiners C, Demidchik YE, Drozd VM, Biko J (2008) Thyroid cancer in infants and adolescents after Chernobyl. Minerva Endocrinol 33(4):381–395

Strauss J, Thomas D (1998) Health, nutrition, and economic development. J Econ Lit 36(2):766–817

UNDP (2002) The human consequences of the chernobyl nuclear accident: a strategy for recovery. A report commissioned by UNDP and UNICEF with the support of OCHA and WHO, 25 Jan. 2002

Vykhovanets EV, Chernyshov VP, Slukvin II, Antipkin YG, Vasyuk AN, Klimenko HF, Strauss KW (1997) ¹³¹I dose-dependent thyroid autoimmune disorders in children living around Chernobyl. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 84(3):251–259

WHO (2006) Health effects of the Chernobyl accident and special health care programmes. WHO, Geneva, ISBN 978 92 4 159417 2

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Štěpán Jurajda, Randall K. Filer, Mykhaylo Salnykov, Kateryna Bornukova, Lauren Heller, Christopher Jepsen and the participants of the seminar at BEROC for their valuable comments. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Food & Drug Administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9131-3.

Appendix

Appendix

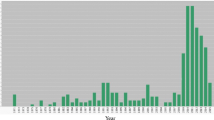

Population trends by region and by area of exposure to radiation, 1969–2009. Data for 1969–1999 is taken from the Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Belarus, ed. 2002. Data for 2009 is taken from the National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus web-site http://belstat.gov.by/homep/en/main.html, accessed on 05.25.2011. The vertical dashed line marks year 1986

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yemelyanau, M., Amialchuk, A. & Ali, M.M. Evidence from the Chernobyl Nuclear Accident: The Effect on Health, Education, and Labor Market Outcomes in Belarus. J Labor Res 33, 1–20 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9122-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-011-9122-9