Abstract

This paper studies the predictive power of external imbalances for exchange rate returns. We focus on Switzerland, a very open economy where exchange rate movements have a strong effect on external imbalances through valuation effects and trade flows. Using a simple modification of the Gourinchas and Rey (J Polit Econ 115(4):665–703, 2007) approach to make their approximation applicable to Switzerland, we find that measures of deviations from trends in Swiss net foreign assets and net exports help to forecast Swiss franc nominal effective exchange rate movements, both in and out of sample.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We follow the timing convention of GR and measure assets and liabilities at the beginning of the period.

The approximation proposed in Whelan (2008) for the household budget constraint works only if net saving is negative, as is the case for US data. But in an internet appendix Whelan (2008) shows that with an adjustment very similar to the one used here his approximation works also in the general case. While Whelan (2008) approximates the household budget constraint in levels, we approximate countries’ external budget constraints around the trends in external positions and trade flows.

Evans (2012) rewrites the accumulation identity as \(A_{t+1}-L_{t+1} = R_{t+1} \left (A_{t}-L_{t} + X^{\ast }_{t}-M^{\ast }_{t}\right )\), where \(X^{\ast }_{t} \equiv X_{t} + \tau _{t}\) and \(M^{\ast }_{t} \equiv M_{t} + \tau _{t}\).

When solving (17) forward, we use a period t approximation around \(\epsilon _{t+1}^{a}=\epsilon _{t+1}^{l}=0\) and a period t+1 approximation around \(\epsilon _{t+1}^{a\ast }=\epsilon _{t+1}^{l\ast }=0\). The two are compatible since we compute trends so that \(\bar {A}_{t}^{\ast }=\bar {A}_{t}+\bar {\tau }^{a}_{t}\). This ensures that \({\epsilon _{t}^{a}}=0\) if and only if \(\epsilon _{t}^{a\ast }=0\). Following GR, we use an HP-filter for detrending. The trend of \(\hat {A}_{t}^{\ast }\) is then computed as

$$\bar{A}_{t}^{\ast }=\bar{A}_{t}+\bar{\tau}^{a}=e^{HP\left( \ln \hat{A}_{t}\right) }+e^{HP\left( \ln \tau^{a}\right) } $$where \(HP(\ln \hat {A}_{t})\) denotes the HP-filtered series \(\ln \hat {A}_{t}\).

We thank Philip Lane for providing us with an updated version of this dataset.

In the GR dataset, US dollar one-quarter depreciation rates computed with trade weights and FDI weights exhibit a correlation coefficient of 0.86 over the 1973-2004 sample.

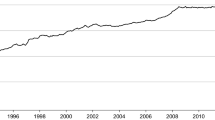

The increase in Switzerland’s net foreign assets has been smaller than what is implied by the size of current account surpluses. This is because of valuation changes, as discussed in Stoffels and Tille (2007). Note also that the economically relevant size of the current account surplus is smaller than its measured size. See Jordan (2013) and IMF (2012, annex I) on this point.

We follow GR and detrend all variables (in logs) using an HP filter with λ = 2400000, filtering out only long-term trends.

The original GR measure nxa turns out to be highly correlated with nxa ∗, although its absolute approximation error is larger, and its predictive power for exchange rate returns is weaker.

We find that in practice it makes little difference how the adjustment is distributed over τ a and τ l. See Section 5.3 below.

To compute the approximation error we need data on the ex-post portfolio return R t . Rather than constructing this from data on portfolio shares and returns on individual assets and liabilities, we compute R t as implied by the accumulation identity (1), given data on net foreign assets and net exports.

In constructing nxa ∗ we use extrapolation at the end of the rolling sample when computing quarterly series for external assets and liabilities from annual data. Also, we recompute \(\tau =\max (\hat {NX}_{t}) + 0.01\) for each rolling window to make sure that we use only information contained in the in-sample.

Unlike Meese and Rogoff (1983) we test ex-ante forecasting power.

As Clark and West (2006) show, under the null of no predictability, β 1 = 0 in regression (24), the MPSE of the unrestricted model, MSPE nxa , is expected to be larger than that of the random walk. This is the case because in the unrestricted model parameters are estimated which under the null have no predictive power.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this explanation.

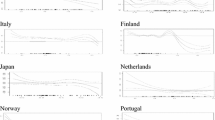

The results are weaker for the longer 1973-2014 sample, especially for Japan. Perhaps this is the case due to the large exchange rate adjustments in the aftermath of the Bretton Woods system.

Other popular risk measures, such as the VIX or VXO index of option-implied US stock market volatility, are only available from 1986.

References

Alquist R, Chinn MD (2008) Conventional and unconventional approaches to exchange rate modelling and assessment. Int J Finance Econ 13(1):2–13

Baharumshah AZ, Khim-Sen Liew V (2006) Forecasting performance of exponential smooth transition autoregressive exchange rate models. Open Econ Rev 17:235–251

Bernanke BS, Laubach T, Mishkin FS, Posen AS (2001) Inflation targeting: lessons from the international experience. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Campbell JY, Shiller RJ (1988) The dividend-price ratio and expectations of future dividends and discount factors. Rev Financ Stud 1(3):195–228

Campbell JY, Mankiw NG (1989) Consumption, income, and interest rates: reinterpreting the time series evidence. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1989 4:185–246

Cardarelli R, Konstantinou PT (2007) International financial adjustment: evidence from the G6 countries, unpublished working paper

Clark TE, West KD (2006) Using out-of-sample mean squared prediction errors to test the martingale difference hypothesis. J Econ 135(1-2):155–186

Della Corte P, Riddiough SJ, Sarno L (2015). Currency premia and global imbalances, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2280952orhttp://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2280952

Della Corte P, Sarno L, Sestieri G (2012) The predictive information content of external imbalances for exchange rate returns: how much is it worth? Rev Econ Stat 94(1):100–115

Elliott G, Müller UK (2006) Efficient tests for general persistent time variation in regression coefficients. Rev Econ Stud 73(4):907–940

Evans MDD (2012) International capital flows and debt dynamics, IMF Working Paper 12/175, July 2012

Evans MDD (2014) External balances, trade flows and financial conditions. J Int Money Financ 48(part B):271–290

Goldberg LS, Klein MW (2011) Evolving perceptions of central bank credibility: the ECB experience, NBER International Seminar in Macroeconomics 2010, 153–182

Gourinchas P-O, Rey H (2007) International financial adjustment. J Polit Econ 115(4):665–703

Gourinchas P-O, Rey H, Truempler K (2012) The financial crisis and the geography of wealth transfers. J Int Econ 88(2):266–283

Grisse C, Nitschka T (2015) On financial risk and the safe-haven characteristics of Swiss franc exchange rates. J Empir Finance 32:153–164

Iliopulos E, Miller M (2007) UK external imbalances and the Sterling: are they on a sustainable path? Open Econ Rev 18:539–557

IMF (2012). Switzerland: staff report for the 2012 article IV consultation, available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25895.0

Jordan T (2013) Reconciling Switzerland’s minimum exchange rate and current account surplus, speech given at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, available at http://www.snb.ch/en/mmr/speeches/id/ref_20131008_tjn

Lane PR, Milesi-Ferretti GM (2001) The external wealth of nations: measures of foreign assets and liabilities for industrial and developing countries. J Int Econ 55 (2):263–294

Lane PR, Milesi-Ferretti GM (2007) The external wealth of nations mark II: revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970-2007. J Int Econ 73(2):223–250

Lane PR, Shambaugh JC (2010) Financial exchange rates and international currency exposures. Am Econ Rev 100(1):518–540

Lettau M, Ludvigson S (2001) Consumption, aggregate wealth, and expected stock returns. J Financ 56(3):815–849

Meese RA, Rogoff K (1983) Empirical exchange rate models of the seventies: do they fit out of sample? J Int Econ 14(1-2):3–24

Pippenger MK, Goering GE (1998) Exchange rate forecasting: results from a threshold autoregressive model. Open Econ Rev 9:157–170

Ranaldo A, Söderlind P (2010) Safe haven currencies. Eur Finan Rev 14(3):385–407

Rich G (2003). Swiss monetary targeting 1974-1996: the role of internal policy analysis, ECB working paper no. 236, June 2003

Rossi B (2013) Exchange rate predictability. J Econ Lit 51(4):1063–1119

SNB (2007) The Swiss National Bank 1907-2007, Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zürich. Also available at http://www.snb.ch/en/iabout/snb/id/snb_100%23t5

Stoffels N, Tille C (2007). Why are Switzerland’s foreign assets so low? The growing financial exposure of a small open economy, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report no. 283, April 2007

Whelan K (2008) Consumption and expected asset returns without assumptions about unobservables. J Monet Econ 55(7):1209–1221

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Katrin Assenmacher, Sylvia Kaufmann, Pinar Yeşin, anonymous referees of this journal and of the SNB working paper series, and participants at the SNB brown bag seminar, the 2013 annual meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics (Neuchâtel), the 4th conference on recent developments in macroeconomics (ZEW Mannheim), and the 7th International Workshop “Methods in International Finance Network” (Namur) for helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Swiss National Bank.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grisse, C., Nitschka, T. Exchange Rate Returns and External Adjustment: Evidence from Switzerland. Open Econ Rev 27, 317–339 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-015-9376-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-015-9376-6