Abstract

Trade in goods that are not perfect substitutes can considerably change the predictions of standard neoclassical models about the effects of demographic developments. This paper considers a relative decrease in the population size of one country, when countries specialize in the production of different intermediate goods. The degree of substitutability is crucial for the direction of capital flows between the countries and for the development of wages. The less those goods are substitutes, the stronger the long-run international spillover effects of a demographic shock will be. For the interest rate effects, also international differences in saving rates due to e.g., different pension schemes have to be taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Northern Europe includes Denmark, Estonia, Faeroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Eastern Europe consists of Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Moldova, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine. Southern Europe includes Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, Portugal, San Marino, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain and TFYR Macedonia. Western Europe consists of Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands and Switzerland.

See the next section for a more extensive description of such a shock.

Here we follow e.g., Aghion et al. (2005) and Carlstrom and Fuerst (2005) where the production of a final good solely depends on a number of intermediate goods. An alternative specification would be to have domestic and foreign goods as imperfect substitutes in the utility function, as well as the investment good being a bundle of domestic and foreign goods with the same elasticity of substitution. This would give the same results.

Throughout the paper, variables denoted in capital (small) letters are in terms of final (intermediate) goods.

Allowing for mortality risk, so that only a fraction of the young survive to the next period, does not change our results qualitatively. Furthermore, changes in mortality do not give results that are fundamentally different from the standard model with one good.

In case of a more general CES-utility function, savings would also depend on the interest rate. This would complicate the derivations but not change the main results. In Section 5, when public pensions are included, the interest rate does appear in the savings function.

The relative size of the population at time t equals \(\frac {L_{t}}{\tilde {L_{t}}} = \frac {L_{0}}{\tilde {L_{0}}} \left (\frac {1+n}{1+\tilde {n}} \right )^{t}\), so if n gets permanently lower [higher] than \(\tilde {n}\), \(\frac {L_{t}}{\tilde {L_{t}}}\) will tend to zero [infinity] in the long run (t → ∞). Hence, the decrease in population growth can only be temporary. Of course, the same results apply if the Foreign country has a temporarily higher rate of population growth, or a temporary drop in the growth rate that is smaller than in Home, and if the working population in the Home country decreases for other reasons.

The current model boils down to the standard one-sector model for 𝜃 → ∞. Indeed, Eq. 19 can then be written as \(K_{t}/L_{t} = \tilde K_{t} / \tilde L_{t}\).

Accoring to Heer and Maussner (2004), the number of transitional periods is about 3 times the number of overlapping generations, in our model this would imply about 6 transitional periods.

Allowing for a fixed replacement rate and variable contribution rates does not change the results of this paper.

This would, for instance, resemble two regions in Europe: “Home” being the southern part (Italy, Spain, Greece) which will be ageing stronger and has lower national savings compared to “Foreign” being the northern part (Germany, the UK, Scandinavian countries).

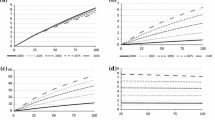

The underlying parameter values are: α = 0.3, β = 1, \(n=\tilde n = 0\), 𝜃 = 2, τ = 0.2 and \(\tilde \tau =0.1\). Initially, the countries are equally large; in period 1, n drops to -0.2, after which it returns to its original level. The same results hold, qualitatively, if other values of the parameters are used.

Note that in the standard one-good model, such a difference does not exist, and the capital-labour ratio would rise in both countries. This can be explained by the fact that the country with the relatively extensive payg-scheme becomes smaller, so average per-capita savings in both countries together will increase.

References

Adema Y, Meijdam AC, Verbon HAA (2008) Beggar thy thrifty neighbour: The international spillover effects of pensions under population ageing. J Popul Econ 21(4):933–959

Aghion P, Redding S, Burgess R, Zilibotti F (2005) Entry liberalization and inequality in industrial performance. J Eur Econ Assoc 3(2–3):291–302

Armington P (1969) A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. Int Monet Fund Staff Pap 16(1):159–178

Bajona C, Kehoe T (2010) Trade, growth, and convergence in a dynamic Heckscher-Ohlin model. Rev Econ Dyn 13:487–513

Baxter M (1992) Fiscal policy, specialization, and trade in the two-sector model: the return of Ricardo? J Polit Econ 100(4):713–744

Blonigen BA, Wilson WW (1999) Explaining Armington: what determines substitutability between home and foreign goods? Can J Econ 32(1):1–21

Börsch-Supan A, Ludwig A, Winter J (2006) Ageing, pension reform, and capital flows: a multicountry simulation model. Economica 73(292):625–658

Carlstrom C, Fuerst TS (2005) Investment and interest rate policy: a discrete time analysis. J Econ Theory 123:4–20

Casarico A (2001) Pension systems in integrated capital markets. Top Econ Anal Policy 1(1):Article 1

Cutler DM, Potreba J, Sheiner L, Summers L (1990) An aging society: opportunity or challenge? Brook Pap Econ Act 1:1–73

Deardorff A, Hanson J (1978) Accumulation and a long-run Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. Econ Inq 16:288–292

Heer B, Maussner A (2004) Dynamic general equilibrium modeling. Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg

Ito H, Tabata K (2010) The spillover effects of population aging, international capital flows, and welfare. J Popul Econ 23:665–702

Kenc T, Sayan S (2001) Demographic shock transmission from large to small countries. An overlapping generations CGE analysis. J Policy Model 22:677–702

Naito T, Zhao L (2009) Ageing, transitional dynamics, and gains from trade. J Econ Dyn Control 33:1531–1542

Oniki H, Uzawa H (1965) Patterns of trade and investment in a dynamic model of international trade. Rev Econ Stud 32:15–38

Samuelson PA (1948) International trade and the equalisation of factor prices. Econ J:163–184

Sayan S (2005) Heckscher-Ohlin revisited: implications of differential population dynamics for trade within an overlapping generations framework. J Econ Dyn Control 29:1471–1493

Shiells CR, Stern RM, Deardorff AV (1986) Estimates of the elasticities of substitution between imports and home goods for the United States.WeltwirtschaftlichesArch 122:497–519

Yakita A (2012) Different demographic changes and patterns of trade in a Heckscher-Ohlin setting. J Popul Econ 25:853–870

Acknowledgments

The authors thank two anonymous referees for their useful comments. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedotenkov, I., van Groezen, B. & Meijdam, L. Demographic Change, International Trade and Capital Flows. Open Econ Rev 25, 865–883 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9311-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9311-2