Abstract

In September 2007, Northern Rock—the fifth largest mortgage lender in the United Kingdom—experienced an old-fashioned bank run, the first bank run in the U.K. since the collapse of City of Glasgow Bank in 1878. The run had been contained by the government’s announcement that it would guarantee all deposits in Northern Rock. This paper analyzes spillover effects during the Northern Rock episode and shows that both the bank run and the subsequent bailout announcement had significant effects on the rest of the U.K. banking system, as measured by abnormal returns on the stock prices of banks. The paper also shows that the effects were a rational response by investors to market news about the liability side of banks’ balance sheets. In particular, banks that rely on funding from wholesale markets were significantly affected, a result consistent with the drying up of liquidity in wholesale markets and the record-high levels of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) during the crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The financial turmoil that started in the summer of 2007 once again showed that crises and bank runs are an important feature of our financial landscape.Footnote 1 In September 2007, Northern Rock experienced an old-fashioned bank run: Depositors formed long queues in front of its branches to withdraw their money. This marked the first bank run in the United Kingdom since the collapse of City of Glasgow Bank in 1878. Eventually, the run was contained by the government’s announcement that it would guarantee all deposits in Northern Rock.

Spillover of difficulties from one bank to the rest of the system is a prime concern for authorities and is the main rationale for the regulation of the financial system. Losses and other difficulties can spill over to the rest of the system through various channels, such as direct exposures via interbank linkages (Allen and Gale 2000); information spillover, where difficulties of one bank can be interpreted as a bad signal for the soundness of other banks (Chen 1999); and illiquidity and asset prices (Diamond and Rajan 2001; Gorton and Huang 2004; Cifuentes et al. 2005).

This paper uses an event-study methodology to analyze the Northern Rock episode and detect spillover effects on the rest of the U.K. banking system.Footnote 2 We use stock price reactions to investigate the presence of spillover. Event studies in the literature usually test spillover by comparing the “normal” return of a stock, as predicted by a standard market equilibrium model such as the CAPM, estimated using historical data, with the actual returns on the day of the event or during a window around the event date. Significant abnormal returns for other banks are regarded as evidence of spillover effects.

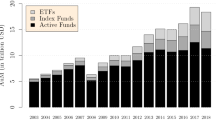

This paper shows that, during the Northern Rock episode, both the bank run and the bailout announcement had spillover effects on the rest of the banking system, as measured by significant abnormal returns on the stock prices of banks. It also shows that the spillover effects were a rational response by investors to market news and can be explained by the characteristics of affected banks: in particular, banks that rely on wholesale markets for funding were affected severely. This finding is consistent with developments in the financial markets prior to the run on Northern Rock, where liquidity dried up in debt and interbank markets, leading to record-high levels of LIBOR (see Fig. 1). Hence, the spillover is associated with the liability side of bank balance sheets rather than the asset side.

This paper is related to the literature on bank runs (Bryant 1980; Diamond and Dybvig 1983; Allen and Gale 1998; Calomiris and Kahn 1991; Chari and Jagannathan 1988 and others) and their origins (Gorton 1988; Calomiris and Gorton 1991) as well as runs in wholesale funding markets (Huang and Ratnovski 2008, 2009). It is also related to event studies in the empirical banking literature that analyze spillover by testing whether bad news—such as a bank failure, the announcement of an unexpected increase in loan-loss reserves, bank seasoned stock issue announcements, etc.—adversely affects other banks.Footnote 3 These studies use a variety of indicators such as intertemporal correlation of bank failures (Hasan and Dwyer 1994; Schoenmaker 1996), bank debt risk premiums (Carron 1982; Saunders 1987; Cooperman et al. 1992; Jayanti and Whyte 1996; Morgan and Stiroh 2001), deposit flows (Saunders 1987; Saunders and Wilson 1996; Schumacher 2000), survival times (Calomiris and Mason 1997, 2003), and stock price reactions (Aharony and Swary 1983; Swary 1986; Slovin et al. 1992, 1999; Lang and Stulz 1992).

Section 2 provides a discussion of the Northern Rock episode. Section 3 discusses the two events that are studied here, and the event-study methodology employed, prior to analyzing the abnormal returns and their relation to bank characteristics. Section 4 concludes.

2 A summary of the Northern Rock crisis

Box 1 presents a timeline of the events during the Northern Rock episode.Footnote 4

Since its conversion from a building society—a residential mortgage lender owned by its savers and borrowers—to a stock-form U.K. bank in 1997, Northern Rock grew remarkably to become Britain’s fifth biggest mortgage provider. Northern Rock’s success depended crucially on a particular business model that relied heavily on securitization and funding from wholesale markets, rather than the traditional banking model of funding from retail deposits and holding the loans on the balance sheet until maturity.Footnote 5 Even though retail deposits can be more costly, many banks still prefer them because they are a more stable source of funding, compared to wholesale funding.Footnote 6

The business model of Northern Rock made it vulnerable to adverse developments in wholesale markets. In the summer of 2007, the ongoing increase in arrears on U.S. subprime mortgages led to a sharp increase in credit spreads on U.S. subprime securities. Information problems associated with complex financial structures led to uncertainty about the nature and the source of losses and, from July on, spreads on asset-backed securities rose in world markets. This led to a drying up of liquidity in short-term debt markets such as the asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) market, on which conduits and structured investment vehicles (SIV) rely. Conduits and SIVs were mainly set up by banks as off-balance-sheet entities that allow banks to extend their lending without the pressure of regulatory capital requirements, and most conduits and SIVs had back-up liquidity facilities with banks. When the ABCP market ceased to provide the needed liquidity, conduits had no choice but to tap their bank lines of credit. This resulted in many of the risks that were thought to be off banks’ balance sheets rushing back to those balance sheets, creating an enormous strain on bank liquidity. Uncertainty about liquidity needs led banks to hoard liquidity rather than lend it in markets, which resulted in a drying up of liquidity in wholesale markets and the LIBOR reaching record-high levels (see Fig. 1).

The developments in financial markets adversely affected Northern Rock, which relied on securitization and wholesale markets for funding. On August 13, 2007, Northern Rock told the Financial Services Authority about its difficulties. This information had also been shared with the Bank of England and the Treasury.Footnote 7 By mid-September, the longer-term funding markets were closed to Northern Rock. While the possibility of the Bank of England acting as a lender of last resort had been discussed among the authorities, the option of selling Northern Rock to another bank had been tried first. Although Lloyds TSB emerged as a serious contender, the deal did not go through because Lloyds’ demand for a loan from the Bank of England had been rejected by the tripartite authorities on the grounds that it would not be appropriate to help finance a bid by one bank for another.Footnote 8 On September 13, the authorities agreed that the Bank of England should provide emergency assistance to Northern Rock. On the same day, on its evening news, the BBC revealed that Northern Rock had asked for and been granted emergency support from the Bank of England. The government put out a public statement on Friday, September 14, confirming that the Bank of England would be ready to act as a lender of last resort.

These developments confirmed the extent of the bank’s difficulties and resulted in a depositor run on Northern Rock. On the evening of Monday, September 17, the government announced that it would guarantee all of Northern Rock’s existing deposits during the current instability in the financial markets. On September 19, the Bank of England announced that it would inject £10 billion into the money markets to bring down the cost of borrowing in the interbank market. Furthermore, the assets that banks are allowed to use as collateral were extended to include mortgage debt. The government guarantee for Northern Rock deposits was extended on September 20 to cover existing (and renewed) unsecured wholesale funding.Footnote 9

3 Model and results

This section discusses the two events analyzed, the event-study methodology employed, and the abnormal returns and their relation to bank characteristics.

3.1 Data and events

The ten largest U.K.-owned banks we focus on, which accounted for around 90 percent of U.K.-owned banks’ assets, are: Abbey National, Alliance & Leicester (A&L), Barclays, Bradford & Bingley (B&B), HBOS, HSBC, Lloyds TSB, Northern Rock (NR), Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), and Standard Chartered (SC). Stock market data for these ten banks and the FTSE All-Share index, which are publicly available, are used. This analysis concentrates on the following two events:

-

(1)

On September 13, 2007, at 20:30, the BBC revealed that Northern Rock had asked for and been granted emergency financial support from the Bank of England. On September 14, the authorities announced a standby facility that would enable Northern Rock to fund its operations during the current period of turbulence in financial markets. On the same day, queues started to form outside Northern Rock branches. To analyze the impact of the bank run on other banks, this study uses stock market returns on Friday, September 14 and Monday, September 17.

-

(2)

On September 17, at around 16:30 in the afternoon, the government announced it would guarantee all existing deposits in Northern Rock. To analyze the impact of the bailout, this study uses stock market returns on Tuesday, September 18.Footnote 10

Table 1 shows the raw stock returns for the above dates.

3.2 Measurement of abnormal returns

We use the standard market model to estimate the daily expected firm returns as follows:

where R it and R mt are the rates of return of bank i and the FTSE All-Share index at date t, respectively. The error term ε it is assumed to have zero mean, to be independent of R mt , and to be uncorrellated across firms.

An OLS regression, with the Newey-West HAC adjustment to control for the presence of autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity, is run to estimate \( \widehat{\alpha }_{i}\) and \(\widehat{\beta }_{i}.\) Abnormal returns, AR it , are calculated as the difference between the realized return and the estimated return from the OLS regression:

The parameters of the market model are estimated using a T = 250 trading day (1 year) window, beginning 270 days before the event date (September 14, 2007).

To determine whether abnormal returns are significantly different from zero, we calculate standardized abnormal returns as:

where \(\widehat{\sigma }_{it}\) is the sample standard deviation of the abnormal return.

To determine the abnormal returns for a period of \(t_{1}\leqslant t\leqslant t_{2},\) we use cumulative abnormal returns defined as

where the standard deviation of the cumulative abnormal returns is given as \( \widehat{\sigma }_{i}(t_{1},t_{2})=\left( \sum\limits_{t=t_{1}}^{t_{2}} \widehat{\sigma }_{it}\right) ^{1/2}\). Hence, we have the standardized cumulative abnormal returns given as:

3.3 Results on abnormal returns

Table 2 reports daily and cumulative abnormal returns.

First, we analyze how the run on Northern Rock on September 14 and 17 affected other banks. The results show that Bradford & Bingley (−5.8 percent) and Northern Rock (−28.9 percent) experienced strong negative abnormal returns (significant at the 1 percent level) on September 14. On the same day, Alliance & Leicester, HBOS and Lloyds TSB also experienced negative abnormal returns (significant at the 10 percent level). On September 17, the difficulties of Northern Rock had a strong spillover effect on the rest of the banking system, as confirmed by the negative abnormal returns for Alliance & Leicester (−29.3 percent), Bradford & Bingley (−13.0 percent), HBOS (−3.6 percent) (all significant at the 1 percent level), and RBS (−2.6 percent, significant at the 5 percent level). Moreover, the results show significant negative abnormal returns for Alliance & Leicester (−34.8 percent), Bradford & Bingley (−18.8 percent) and HBOS (−5.7 percent) during the event window of September 14–17. Overall, we find that, during the event window of September 14–17, the difficulties of Northern Rock had negative spillover effects on a significant portion of the U.K. banking system.Footnote 11

Second, we analyze the effect of the bailout announcement on September 17.Footnote 12 The results show significant positive abnormal returns for Alliance & Leicester (30.7 percent), Barclays (2.6 percent), Bradford & Bingley (4.3 percent), RBS (2.0 percent), and to some extent Abbey (1.6 percent, significant at the 10 percent level) on September 18.Footnote 13 The announcement had a positive effect on the share price of Northern Rock on September 18, but not a significant one. Also, Northern Rock experienced significant negative abnormal returns (−19.5 percent) on September 19. Hence, the bailout announcement prevented the spillover effects, but at that point the market seemingly was convinced about the difficulties of Northern Rock, and the announcement could not prevent further negative abnormal returns and the institution’s eventual failure.

3.4 Abnormal returns and bank characteristics

An important question is whether the effects were the result of a panic or whether they were a rational response by investors to market news and attributable to the characteristics of affected banks. To analyze whether the spillover from Northern Rock to other banks (and the effect of the bailout announcement) was the result of similarities between Northern Rock and the affected banks, we looked at the relation between abnormal returns and various bank balance sheet features such as customer deposits (deposit), wholesale funding (wholesale),Footnote 14 shareholders’ equity (capital) on the liability side, and total assets (size) and mortgage loans (mortgage) on the asset side. Table 3 shows balance sheet data for the ten banks.

Northern Rock had a particular business model. On the asset side, mortgage loans constituted 77 percent of the institution’s assets. On the liability side, Northern Rock had a small depositor base (27 percent of liabilities came from customer deposits), whereas most of its liabilities came from wholesale funding (68 percent of liabilities from interbank deposits and debt securities in issue). Hence, if the spillover from the run on Northern Rock to other banks was a rational response by investors, one would expect mortgages and wholesale funding to negatively affect abnormal returns, whereas customer deposits would positively affect abnormal returns. One role of capital is to act as a cushion for negative shocks. Thus, we would expect shareholders’ equity to have a positive effect on abnormal returns. One can think of big banks having easy access to markets and possibly enjoying implicit too-big-to-fail guarantees such that size would have a positive effect on abnormal returns. Also, banks that were affected negatively by the run on Northern Rock could have been expected to experience positive effects from the bailout announcement. In other words, one would expect the balance sheet characteristics to have opposite effects on abnormal returns as a result of the run on Northern Rock (September 14 and 17) and the bailout announcement (September 18).

To analyze the effect of bank characteristics on abnormal returns, we run a series of OLS regressions, in which Northern Rock is excluded from the sample.Footnote 15 In these regressions, the dependent variable is the abnormal return during the period of interest and the explanatory variables are the bank balance sheet characteristics discussed above. Four sets of OLS regressions are run: one for each date of September 14, 17, and 18, and one for the period September 14–17. The regression results are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

For each set of regressions, the tables report the results for three different model specifications. Table 4 presents the simple regression results, and Table 5 presents the results from multiple regressions. In particular, in Table 5, model (i) presents the model with the most comprehensive set of explanatory variables, whereas model (ii) presents the specification selected by the Akaike and Schwarz information criteria.

The simple regression results in Table 4 show that wholesale is the only explanatory variable that is significant in explaining abnormal returns for all four periods of interest in this study.Footnote 16 The results are very strong as wholesale is significant at the 1 percent level in all regressions, except for September 18, where the p-value is 0.02. From the simple regression results, we also observe that mortgage has some explanatory power for abnormal returns on September 14, September 17 and September 14–17 (significant at the 5, 10, and 10 percent levels, respectively), whereas it is not significant at the 10 percent level for September 18.Footnote 17 These results are consistent with the main features of Northern Rock’s business model: On the asset side, mortgage loans represented a majority of Northern Rock’s assets, and the bank had a small depositor base with most of its liabilities coming from wholesale funding.

The results from the multiple regressions in Table 5 confirm the importance of the explanatory variable wholesale in explaining the abnormal returns during the Northern Rock episode. Model (i) is the model with all five explanatory variables. The results show that wholesale is the only variable that is significant in explaining the abnormal returns.Footnote 18 Furthermore, in all four periods analyzed, the model that has been selected using the Akaike and Schwarz information criteria is the model with wholesale as the unique explanatory variable.

These results show unambiguously that reliance on wholesale markets for funding is the most important bank characteristic explaining the spillover effects during the Northern Rock episode.Footnote 19 Furthermore, the results show that the effects were a rational response by investors and a manifestation of the drying up of liquidity and the resulting funding difficulties in the wholesale markets. The R 2 values show that bank balance sheet characteristics, in many cases, were able to explain around 90 percent of the variation in abnormal returns, which confirms that the spillover effects were a rational response by investors rather than pure panic effects. While the proportion of mortgage loans has some explanatory power, the spillover is associated mainly with the funding sources of banks, suggesting that the liability side and funding characteristics of banks can also be a leading source of bank failures and spillover effects.

Furthermore, as a robustness check, all the regressions were run without including Alliance & Leicester.Footnote 20 Alliance & Leicester is the bank that most closely resembles Northern Rock in terms of its heavy reliance on wholesale markets and its involvement in mortgage origination. But even without including Alliance & Leicester, the results hold. This shows that the results are robust, and are not driven by idiosyncratic factors. Rather, they show systematically that the market participants’ response can be explained by the business model adopted by the affected banks—in particular, their heavy reliance on wholesale funding.Footnote 21

4 Conclusion

In 2007, world financial markets experienced extraordinary events. An important episode was the depositor run on Northern Rock and the U.K. government’s announcement that it would guarantee all deposits to contain the run. This paper shows that both the run on Northern Rock and the subsequent bailout announcement had significant effects on the rest of the banking system. Furthermore, the effects were a rational response by investors to market news and reflected the characteristics of affected banks. In particular, the spillover effects can be explained by banks’ funding characteristics given that banks that rely on funding from wholesale markets were affected severely, a result consistent with the liquidity crunch in debt and interbank markets prior to the run on Northern Rock. Hence, this paper provides an interesting contribution to the literature on whether spillover effects are the result of a panic or a rational response by investors to available information. Furthermore, the results contribute to the discussion on the origins of bank failures by providing evidence that the liability side and funding characteristics of banks can be a leading source of bank failures and spillover effects.

Notes

Lindgren et al. (1996) show that, during the period 1980–96, of the 181 IMF member countries, 133 experienced significant banking problems. Such problems have affected developed as well as developing and transitional countries. Also see Dell’Ariccia et al. (2008) for an analysis of the real effects of banking crises.

See De Bandt and Hartmann (2002) for an excellent survey of theoretical and empirical models of systemic risk and the references therein for further discussion.

The timeline and the discussion here rely on the description of the Northern Rock episode in the October 2007 Financial Stability Report of the Bank of England (2007); the articles “Down the Drain” and “Lessons of the Fall” in the September 6, 2007 and October 18, 2007 issues of The Economist, respectively; and the BBC website: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7007076.stm.

Northern Rock had only 76 branches in 2007 and retail deposits accounted for only 27 percent of its liabilities, whereas wholesale funding accounted for 68 percent of its liabilities, according to its interim results in June 2007. In January and May 2007, Northern Rock raised £10.7 billion through securitization, which made it the top securitizer among British banks.

This can arise due to the costs associated with changing banks that unsophisticated depositors incur, such as switching and searching costs. For example, data collected on current account switching behavior from the Financial Research Survey of the National Opinion Poll for the UK imply that a representative current account holder would only change banks every 91 years (Gondat-Larralde and Nier 2006).

According to the tripartite structure, the Bank of England, the Financial Services Authority, and the Treasury are mandated to deal with financial crises.

Acharya and Yorulmazer (2008) analyze various policy options to resolve bank failures such as liquidation, bailouts, and sale of a failed bank to a healthy bank, with and without government assistance. They show that, from a social welfare point of view, the sale of a failed bank to a healthy bank with government assistance can be preferable to bailing out the failed bank.

An announcement on September 21 confirmed and clarified the guarantees announced on September 20.

An important issue is whether there were other events, not directly related to the run on Northern Rock that might have confounded the effects. For example, Wall and Petersen (1990) extend Swary’s (1986) analysis of Continental Illinois and show that events related to U.S. banks’ holdings of claims on Latin America were confounding factors that needed to be included in the analysis. One such issue arises in our analysis for the effects of the bailout announcement. On September 19, at around noon, the Bank of England announced an injection of liquidity into the money markets and the extension of collateral to include mortgage debt, in an attempt to ease the liquidity crunch in wholesale markets. Hence, the returns on September 19 can be jointly affected by the bailout announcement on September 17 and the Bank of England’s announcement on September 19. To focus solely on the effect of the bailout announcement, we prefer to concentrate on returns for September 18.

The total assets of the ten banks in the study are approximately £4441 billion, which is around 317 percent of the U.K. GDP (£1401 billion) in 2007. The total assets of Alliance & Leicester, Bradford & Bingley and HBOS—the three banks on which we found significant spillover effects—are approximately £710 billion, which is around 51 percent of the U.K. GDP in 2007. Furthermore, spillover effects during September 14–17 wiped out 59, 32 and 14 percent of Tier 1 capital of Alliance & Leicester, Bradford & Bingley, and HBOS, respectively.

O’Hara and Shaw (1990) study the effect of the announcement of the too-big-to-fail guarantee by the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and find a positive value effect for the largest banks.

On September 19, at around noon, the Bank of England announced an injection of liquidity into the money markets and the extension of collateral to include mortgage debt. As a result, we chose to focus only on September 18 to analyze the effect of the bailout announcement. However, on September 19, Bradford & Bingley experienced a significant positive abnormal return (7.5 percent, significant at the 1 percent level). Hence, the cumulative abnormal return for Bradford & Bingley is 11.8 percent for September 18–19, which would only make the results of the paper stronger. While the failure of Northern Rock is clearly bad news for other banks that pursue the same business model, the announcement on September 18 contains some uncertainty about the government’s future response to difficulties in other banks. Even though the announcement on September 18 may imply that similar guarantees might be provided for other banks in the future, this potential guarantee is not explicit. Hence, the uncertainty about future government interventions still remains, which mitigates the effect of the government intervention. However, one can interpret the announcement on September 19 as indicative of the authorities’ willingness to intervene, which would have reduced the uncertainty about government interventions. Hence, the effects we find for the government intervention could be expected to serve as a lower bound for the effect of the bailout announcement.

Consistent with the October 2007 Financial Stability Report of the Bank of England, we define wholesale funding as the sum of debt securities in issue and the deposits from other banks.

Inclusion of Northern Rock makes the results stronger.

The other three explanatory variables, deposit, size, and capital, mostly have the expected signs, but they are highly insignificant.

Wholesale is significant at the 5 percent level for September 14–17, significant at the 10 percent level for September 14 and September 17, whereas the p-value is 0.12 for September 18.

This finding is consistent with Shin (2009), who argues that Northern Rock’s reliance on institutional investors for short-term funding made it extremely vulnerable to the drying up of liquidity in credit markets.

Results are available from the authors upon request.

A further confirmation for the robustness of our results is the subsequent failures (or near failures) of the institutions we show to have been affected. In particular, in the aftermath of Lehman’s failure, the takeover of Alliance & Leicester by the Spanish bank Grupo Santander was ratified by shareholders on September 16, 2008; the U.K. government announced that Bradford & Bingley had been partly nationalized and that Grupo Santander had purchased the savings business on September 29, 2008; Lloyds TSB’s acquisition of HBOS was announced on September 19, 2008, effective on January 19, 2009; and HBOS’ pre-tax loss of £10.8 billion in 2008 hit Lloyds TSB, which had to be recapitalized by the U.K. government. As the sequence of events confirms, the effects we found were neither spurious nor idiosyncratic; rather, they can be systematically explained by the business model of the affected banks.

References

Acharya V, Yorulmazer T (2008) Cash-in-the-market pricing and optimal resolution of bank failures. Rev Financ Stud 21(6):2705–2742

Aharony J, Swary I (1983) Contagion effects of bank failures: evidence from capital markets. J Bus 56(3):305–317

Allen F, Gale D (1998) Optimal financial crises. J Finance 53:1245–1283

Allen F, Gale D (2000) Financial contagion. J Polit Econ 108:1–33

Bank of England (2007) Financial stability report. October, 22, pp 5–15

Bryant J (1980) A model of reserves, bank runs and deposit insurance. J Bank Financ 4:335–344

Calomiris C, Gorton G (1991) The origins of banking panics: models, facts, and bank regulation. In: Hubbard G (ed) Financial markets and financial crises. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Calomiris C, Kahn C (1991) The role of demandable debt in structuring optimal banking arrangements. Am Econ Rev 81:497–513

Calomiris C, Mason J (1997) Contagion and bank failures during the great depression: the June 1932 Chicago Banking Panic. Am Econ Rev 87(5):863–883

Calomiris C, Mason J (2003) Fundamentals, panics and bank distress during the depression. Am Econ Rev 93(5):1615–1647

Campbell JY, Lo AW, MacKinlay AC (1997) The econometrics of financial markets. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Carron AS (1982) Financial crises: recent experience in U.S. and international markets. Brookings Pap Econ Act 2:395–418

Chari VV, Jagannathan R (1988) Banking panics, information and rational expectations equilibrium. J Finance 43:749–60

Chen Y (1999) Banking panics: the role of the first-come, first-served rule and information externalities. J Polit Econ 107(5):946–968

Cifuentes R, Ferucci G, Shin HS (2005) Liquidity risk and contagion. Journal of the European Economic Association 3(2–3):556–566

Cooperman ES, Lee WB, Wolfe GA (1992) The 1985 Ohio thrift crisis, the FSLIC’s solvency and rate contagion for retail CDs. J Finance 47(3):919–941

De Bandt O, Hartmann P (2002) Systemic risk: a survey. In: Goodhart C, Illing G (eds) Financial crisis, contagion and the lender of last resort: a book of readings. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 249–298

Dell’Ariccia G, Detragiache E, Rajan R (2008) The real effect of banking crises. J Financ Intermed 17(1):89–112

Diamond D, Dybvig PH (1983) Bank runs, deposit insurance and liquidity. J Polit Econ 91:401–419

Diamond D, Rajan R (2001) Liquidity risk, liquidity creation and financial fragility: a theory of banking. J Polit Econ 109:2431–2465

Gondat-Larralde C, Nier E (2006) Switching costs in the market for personal accounts: some evidence for the United Kingdom. Bank of England working paper no 292

Gorton G (1988) Banking panics and business cycles. Oxf Econ Pap 40:751–781

Gorton G, Huang L (2004) Liquidity, efficiency and bank bailouts. Am Econ Rev 94:455–483

Hasan I, Dwyer GP (1994) Bank runs in the free banking period. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 26:271–288

Huang R, Ratnovski L (2008) The dark side of wholesale funding. Working paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Huang R, Ratnovski L (2009) Why are Canadian banks more resilient? IMF working paper no 09/152

Jayanti S, Whyte AM (1996) Global contagion effects of the continental illinois failure. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 6(1):87–99

Lang L, Stulz R (1992) Contagion and competitive intra-industry effects of bankruptcy announcements. J Financ Econ 32:45–60

Lindgren C-J, Garcia G, Saal MI (1996) Bank soundness and macroeconomic policy, international monetary fund. Washington, DC

MacKinlay AC (1997) Event studies in economics and finance. J Econ Lit 35:13–19

Morgan D, Stiroh KJ (2001) Market discipline of banks: the asset test. J Financ Serv Res 20:195–208

O’Hara M, Shaw W (1990) Deposit insurance and wealth effects: the value of being ‘Too Big to Fail’. J Finance 45(6):1587–1600

Saunders A (1987) The interbank market, contagion effects and international financial crises. In: Portes R, Swoboda AK (eds) Threats to international financial stability. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 196–232

Saunders A, Wilson B (1996) Contagious bank runs: evidence from the 1929–1933 period. J Financ Intermed 5:409–423

Schoenmaker D (1996) Contagion risk in banking. L.S.E. Financial Markets Group Discussion Paper, No 239

Schumacher L (2000) Bank runs and currency run in a system without a safety net: Argentina and the ‘Tequila’ Shock. J Monet Econ 46:257–277

Shin HS (2009) Reflections on modern bank runs: a case study of Northern rock. J Econ Perspect 23(1):101–119

Slovin M, Sushka M, Polonchek J (1992) Information externalities of seasoned equity issues: difference between banks and industrial firms. J Financ Econ 32:87–101

Slovin M, Sushka M, Polonchek J (1999) An analysis of contagion and competitive effects at commercial banks. J Financ Econ 54:197–225

Swary I (1986) Stock market reaction to regulatory action in the continental Illinois crisis. J Bus 59(3):451–473

Wall L, Petersen D (1990) The effect of continental Illinois’ failure on the financial performance of other banks. J Monet Econ 26:77–99

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Part of this project was completed while Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham was at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. We are grateful to Viral Acharya, Robert DeYoung (editor), Douglas Gale, Beverly Hirtle, Donald Morgan, Ihab Seblani, David Skeie, Til Schuermann, Hyun Shin, Haluk Unal (editor) and an anonymous referee for helpful suggestions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Yorulmazer, T. Liquidity, Bank Runs, and Bailouts: Spillover Effects During the Northern Rock Episode. J Financ Serv Res 37, 83–98 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0079-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-009-0079-2