Abstract

The Fukushima 1 Nuclear Power Plant accident in March 2011 released an enormously high level of radionuclides into the environment, a total estimation of 6.3 × 1017 Bq represented by mainly radioactive Cs, Sr, and I. Because these radionuclides are biophilic, an urgent risk has arisen due to biological intake and subsequent food web contamination in the ecosystem. Thus, urgent elimination of radionuclides from the environment is necessary to prevent substantial radiopollution of organisms. In this study, we selected microalgae and aquatic plants that can efficiently eliminate these radionuclides from the environment. The ability of aquatic plants and algae was assessed by determining the elimination rate of radioactive Cs, Sr and I from culture medium and the accumulation capacity of radionuclides into single cells or whole bodies. Among 188 strains examined from microalgae, aquatic plants and unidentified algal species, we identified six, three and eight strains that can accumulate high levels of radioactive Cs, Sr and I from the medium, respectively. Notably, a novel eustigmatophycean unicellular algal strain, nak 9, showed the highest ability to eliminate radioactive Cs from the medium by cellular accumulation. Our results provide an important strategy for decreasing radiopollution in Fukushima area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The F1NPP accident led to the discharge of a large quantity of radioactivity into the environment. The gross amount released from the power plant was estimated to be 900 PBq (TEPCO 2012) and the radionuclides were distributed widely into 30 km area around the power plant (Chino et al. 2011). Radioactive Cs, Sr and I released into the air were estimated at 10–37 PBq, 150 TBq and 90–500 PBq, respectively (Chino et al. 2011; Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters 2011; Stohl et al. 2012; TEPCO 2012). Among them, radionuclides released into the ocean were reported as 940 TBq 134Cs, 940 TBq 137Cs, 90–900 TBq 90Sr, and 2.8 PBq 131I (Casacuberta et al. 2013; Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters 2011). In addition, TEPCO has been injecting a large volume of water into the F1NPP reactors for cooling, and a total volume of ~93,370 m3 of highly polluted water had been stored in the reactor and extra tanks by 27 March 2013 (TEPCO 2013). Unfortunately, the amount of radio-polluted water is further increasing day-by-day due to the continuous operation of cool water injection and the incurrent of underground water into the defective reactor. Thus, it is our urgent task to safely recover such a large volume of highly radio-polluted water and eliminate radionuclides below environmentally safety levels.

Among the radionuclides released into the environment, 134Cs, 137Cs, 90Sr, and 129I are easily taken up by organisms, since Cs and Sr are analogs of potassium and calcium, respectively, and iodine is an essential element for many organisms. On the other hand, 89Sr, 131I, 132I, 133I and 135I, which were also released into the environment, decay rapidly due to their short half-life times, i.e., 50.5, 8, 2.3, 0.88 and 0.27 days for 89Sr, 131I, 132I, 133I and 135I, respectively. In addition, 129I was not released directly but has been produced secondarily by the disintegration of released 129mTe (NISA 2011).

The artificial radionuclides 137Cs and 90Sr are monitored in total diet studies in terms of risk management in many countries. 90Sr is of particular concern because of its long half-life (28 years) and its potential risk of deposition in bone (Betsy et al. 2012). On the other hand, iodine is an essential element for higher animals but has negative effects at high concentrations. Some organisms such as brown macrophytes accumulate high concentrations of iodine in the algal body (Carolan et al. 2011; Chowdhury and Blust 2011; Gall et al. 2004; Iwamoto and Shiraiwa 2012; Küpper et al. 1998; Martinelango et al. 2006; Marzano et al. 2000; Rowan and Rasmussen 1994). When organisms ingest drinking water or foods with heavy radiopollution or breathe polluted air, it would increase the risk of suffering radiation problems (Escher and Hermens 2004; Golikov et al. 2004). Because radionuclides can be highly concentrated within the food web, the problems become bigger with time (Dubrova et al. 1996; Fugazzola et al. 1995; Nikiforov and Gnepp 1994). Therefore, a removal of radionuclides from the environment is an urgent task to reduce the risk brought by the radiopollutants.

The development of new technology and engineering strategies are critical to decontamination of radionuclides, which are distributed widely in both terrestrial and aquatic environments at very low concentrations. Chemical methods such as precipitation and adsorption seem not effective for such low quantity radionuclides. Therefore, biological processes or bioremediation strategies are potentially important.

Many terrestrial bioremediation methods have employed terrestrial plants to eliminate radionuclides from the environment since the Chernobyl accident in 1986 (IAEA 2006). The accumulation of radioactive Cs into terrestrial plants such as tea (Mück 1997; Polar 2002), rice (Hosono and Takahashi 2013; Nakanishi et al. 2013; Tanoi et al. 2013), sunflower (Dushenkov et al. 1997), and tomato (Endo et al. 2013) have been reported. In other studies of this issue, the effects of radionuclides released from F1NPP on terrestrial plants have been discussed (Kawai et al. 2014; Kobayashi et al. 2014; Mimura et al. 2014; Ohmori et al. 2014; Sekimoto et al. 2014; Terashima et al. 2014; Yamashita et al. 2014).

In this study, we investigated the ability of algae and aquatic plants to eliminate radionuclides from media, in order to establish a strategy for decontaminating the aquatic environment in Fukushima area. We have screened 188 strains of algae and aquatic plants for strains that possess the ability to efficiently accumulate radionuclides and, hence, are potentially useful for eliminating the radionuclides from the environment.

Materials and methods

Algae and aquatic plants and their culture conditions

In total, 188 strains of algae and aquatic plants were used in this study. Of these strains, 99 strains were from the culture collection of our group; 75 strains coded with NIES were from the culture collection of the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) in Tsukuba, Japan; five strains Is-ta-kw, Ch-deb-2, Ch-n-kw, Th-n-5, and Nd23 × Nd36-3 were provided by Dr. Akira Kuwata (Tohoku National Fisheries Research Institute); five strains coded as TIR 1 to TIR 5 were provided by Ms. Misaka Taira (University of Tsukuba); and four strains coded as We 1 to We 4 were purchased from a local pet shop in Tsukuba, Japan (see Table S1). The strains used in this study were phylogenetically broad organisms classified in cyanobacteria and eukaryotes such as Opistokonta, Excavata, Archaeplastida, Rhizaria, Alveolata and Stramenopiles, as shown in Fig. 1. These organisms show various features in their morphology, physiology and biochemical properties. They also show various nutritional properties such as autotrophic and/or heterotrophic and seawater tolerant or intolerant.

For stock and pre-experimental cultures, marine algal strains were grown in seawater enriched either with ESM, IMK or f/2 medium (Kasai et al. 2004), and freshwater algae and aquatic plants were grown either in C, CS, or AF-6 medium (Kasai et al. 2004).

For radionuclide elimination testing, each freshwater medium was prepared without potassium. Heterotrophs were grown in AF-6 or seawater medium containing organic nutrients such as GPY (4 g l−1 glucose, 2 g l−1 polypeptone, and 1 g l−1 yeast extract) or YT (2 g l−1 triptone and 1 g l−1 yeast extract) (Table S1). All strains were incubated at 20 °C under continuous light of 100 μmol photon m−2 s−1 for several days as indicated in the text.

Global searches for strains with high radionuclide elimination ability

One hundred and eighty-eight strains were grown and tested for their ability to eliminate radionuclides from the medium (Table S1). The test was initiated by the addition of 1,000 Bq ml−1 radionuclides into cultures containing individual strains suspended in 15 ml fresh medium. In our global searches the elimination ability of radionuclides was primarily assessed because this ability is important in our strategy to remove radionuclides from the environment using aquatic plants and algae. After starting cultures, algae and aquatic plants grow differently and therefore the biological mass of individual cultures and strains differed at similar time points. Thus, for normalization, the values of radionuclide elimination ability factored in both the growth activity and the absorption/adsorption activity of radionuclides by organisms. Radionuclides used in this study were 3.7 MBq ml−1 137CsCl (Specific activity, 61.7 GBq mmol l−1; Eckert and Ziegler Isotope Products, Valencia, CA, USA) and 217.2 MBq ml−1 85SrCl2 (Specific activity, 17.6 GBq mmol l−1; Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, USA) and 3.7 G Bq ml−1 125I (carrier free; MP Biomedicals, Inc., Santa Ana, USA). 125I was added as a mixture of iodide (I−) and iodate (IO3 −) in a 1:1 ratio. Iodide was chemically oxidized to iodate by adding 2.0 % H2O2 to the stock solution (Liebhafsky et al. 1978). The concentrations of radionuclides were 2.2 and 7.1 ng ml−1 for Cs and Sr, respectively. However, the value of iodine-radionuclide could not be calculated exactly since carrier-free 125I was added to seawater containing 5.9 μg ml−1 I.

In our global searches, disposable plastic flasks were used as reaction vessels (Culture Flask, 3100-025, IWAKI, Tokyo, Japan). The radionuclides were added to the reaction medium containing algae or aquatic plants previously grown for 24 h. After injection of radionuclides, an aliquot of culture (100 μl) was taken out at 0, 7 and 14 days for photoautotrophs, and 0, 4 and 7 days for heterotrophs. For microalgae, samples were separated into the medium and cell fractions by a silicone-oil layer centrifugation method, as described in our previous paper (Araie et al. 2011).

In case of aquatic plants, each culture medium was also subjected to the same silicone-oil layer centrifugation method to separate small particles from the media. Radioactivity was determined using a gamma-ray counter (Aloka Accuflex γ7000, Tokyo, Japan). The elimination ability of radionuclides was calculated as the difference in the radioactivity in the medium at time 0 and at each sampling time. All experiments were performed at least twice to confirm repeatability of our tests, using multiple cultures for each strain.

Radionuclide elimination tests for selected strains

In our global searches, strains that showed an ability to efficiently eliminate radionuclides from the medium (more than 40 %) were selected and subjected to the secondary test to increase the reliability of our data. Radioactivity measurements were carried out for samples at 0, 2, 4 and 8 days after the addition of each radionuclide. The same experiments were repeated three times for selected strains. In each test, the sample biomass was determined by growing one mock (control) culture that contained no radionuclide: at 8 days of culture, control cells were harvested by centrifugation or filtration, washed with distilled water, and then dried by freeze-drying for ca. 12 h using Lyph Lock 6 (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Dried samples were weighed on an electric precision balance (AG285, Mettler-Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland).

The radioactivity partitioned in the cells, the cell-free medium, and the residual precipitates including particles attached onto a culture flask wall was measured. After 8 days of incubation with radionuclides, cells and medium were separated by passing through a glass filter (Whatman GF/F, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The cells on the filter and the vessels were rinsed with 15 ml each of distilled water twice. Filtrates and medium were combined and stored as a medium fraction. Radionuclides adsorbed on the culture flask wall were eliminated by solubilizing with 5 ml of 5 % sodium dodecyl sulfate and stored as an adherence fraction. The total radioactivity accumulated in filtered cells was measured together with the filter.

Results

Global searches for strains with high radionuclide elimination ability

In order to select algae and aquatic plants that can be served for eliminating radionuclides from the aquatic environment, we searched for stains that accumulated high levels of radioactive Cs+, Sr2+ and I− from the medium as described in the “Materials and methods”. Among 188 strains of algae and aquatic plants examined, 137Cs, 85Sr and 125I were significantly eliminated by 167, 181 and 187 strains, respectively. These organisms are shown in descending order of average ability to eliminate radionuclide from the medium (Fig. 2).

Elimination ability of radionuclides from the culture medium by algae and aquatic plants in the primary (global) screening. a 137Cs; b 85Sr; c 125I. Average values are ranked in descending order. List of all organisms and values are the same as those listed in Table S1. Seawater strains ranked within top 20 in each radionuclide are marked by asterisks

Evaluation of radionuclide elimination ability for selected strains

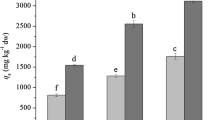

Based on the primary data in Fig. 2, 15, 10 and 14 strains with significantly high elimination ability for 137Cs, 85Sr and 125I, respectively, were selected for further tests (Fig. 3). The elimination time courses of the three radionuclides suggested that radionuclides were mostly eliminated by absorption, but not by simple adsorption onto the surface, since the values increased slowly and rather linearly with incubation times.

Elimination ability of radionuclides from the culture medium by selected algae and aquatic plants in the second screening. a 137Cs; b 85Sr; c 125I. Opened, hatched and closed bars represent values of percent elimination after 2-, 4- and 8-days incubation, respectively. The values (ng g DW−1) indicate the mass of radionuclides accumulated/recovered by cells during 8 days (calculated on the basis of dry weight). The names and strain codes (marked with underline) are the same as those listed in Table 1. Others are as followings: AYCC145, Bangia sp., Rhodophyta; AYCC550, Bangiopsis sp., Rhodophyta; DA 36, Heterosigma akashiwo, Ochrophyta; INB 97, Coelastrum sp., Chlorophyta; nak 13, Tetraselmis sp., Chlorophyta; nak 15, Tetraselmis sp., Chlorophyta; nak 27, Calyptrosphaera sphaeroidea, Haptophyta; nak 1003, Spirogyra sp., Zygnematophyta; NIES-329, Ulothrix variabilis, Chlorophyta; NIES-548, Acinetospora crinite, Ochrophyta; NIES-931, Gloeocapsa decorticans, Cyanobacteria; OS 4, Dixoniella grisea, Rhodophyta; TM 16, Amphidinium massartii, Dinophyta; and We 3, Eleocharis acicularis, Tracheophyta (See also Table S1). Strains We 4 and OS 4 were additionally tested in this screening. Seawater strains are indicated by asterisks

Five strains were selected as highly positive, radioactive Cs eliminators (Table 1). They include three microalgae such as an unidentified freshwater eustigmatophycean strain, nak 9 (ca. 90 % elimination), the freshwater floridephycean Batrachospermum virgato-decaisneanum NIES-1458 (ca. 38 % elimination), the chlorophyte Chloroidium Saccharophilum NIES 2352 (ca. 22 % elimination) and the two aquatic plants (trachiophytes) Lemna aoukikusa TIR 2 and TIR 3 (ca. 45 and 66 % elimination, respectively) (Table 1). Notably, nak 9 displayed an exceptional ability of swift elimination, i.e., as fast as 2 days to reach the steady state level (Fig. 3a).

Three strains showed a high ability to eliminate radioactive Sr. They were the cyanobacterium Stigonema ocellatum NIES-2131 (ca. 41 % elimination), the chlorophycean alga Oedogonium sp. nak 1001 (ca. 36 % elimination) and the Magnoliopsidae Egeria densa We2 (ca. 34 % elimination) (Table 1).

For radioactive I elimination, five stains were promising. They were the cyanophyceans Nostoc commune TIR 4 (ca. 66 % elimination), which shows very high drought tolerance (Fukuda et al. 2008), Scytonema javanicum NIES-1956 (ca. 62 % elimination) and Stigonema ocellatum NIES-2131 (ca. 49 % elimination), the freshwater xanthophycean alga Ophiocytium sp. nak 8 (ca. 42 % elimination), and the aquatic vascular plant Elodea nuttallii We1 (ca. 31 % elimination) (Table 1).

Where did the organisms accumulate the radionuclides absorbed from the medium? To examine this, cells and organisms were incubated with radionuclides for 8 days and then disrupted to separate three fractions, i.e., the cells, the cell-free culture medium, and insoluble precipitates including precipitates from the medium and those recovered from the culture flask wall. Figure 4 clearly shows that radionuclides were mainly deposited into either cells or the cell-free culture medium, but very little into the insoluble materials.

Fractionation of radionuclides from the strain culture medium. After incubation with 137Cs (a), 85Sr (b) and 125I (c) for 8 days, the radioactivity recovered in the cells (open bar), the precipitates (hatched bar) and the soluble materials (closed bar) from the medium was determined. The names of strains are the same as shown in Fig. 3, except nak 8 (Ophiocytium sp., Ochrophyta) and TIR 4 (Nostoc commune, Cyanobacteria) (See also Table S1). All these strain codes are underlined in Table 1

Selection of useful strains with an ability to eliminate multiple radionuclides

Some of microalgae and aquatic plants eliminated multiple radionuclides from the medium (Fig. 5). L. aoukikusa (Tracheophyta) TIR 3 and TIR 4 exhibited relatively high elimination efficiency (25–78 % elimination) for 137Cs, 85Sr and 125I from the media (Fig. 5, marked with H and I). However, we could not find any strain that could efficiently eliminate all of the above radionuclides from the medium (>90 % elimination).

Comparison between the abilities of selected strains to eliminate two different radionuclides in the radionuclide elimination test. a 137Cs vs. 85Sr; b 137Cs vs. 125I; c 125I vs. 85Sr. Strains: A nak 8; B nak 9; C nak 1001; D nak 1002; E NIES-1458; F NIES-1956; G NIES-2131; H TIR 3; I TIR 4; J We 2; and asterisk unicellular strain. The names of strains are listed in Figs. 3 and 4 (See also Table S1)

Effect of potassium on radioactive cesium elimination

The freshwater unidentified eustigmatophycean strain nak 9 was the best microalgae for radioactive Cs accumulation/elimination (Table 1; Figs. 3, 4). Using this strain, the effect of potassium on Cs-elimination ability was tested (Fig. 6). The elimination ability became substantial after 4 h incubation, but this ability was suppressed by exogenously supplied potassium, depending on the concentration of potassium. These results suggested that 137Cs is taken up by the cells in a competitive manner with potassium (Fig. 6). However, the exact mechanism for 137Cs absorption by the cells remains to be elucidated (see “Discussion”).

Effect of potassium on the ability of the eustigmatophycean strain nak 9 to eliminate radioactive Cs. Algal cells were firstly grown in the potassium-deficient AF-6 medium for 14 days and then transferred to the fresh medium containing 137Cs (10 MBq l−1). Various concentrations of potassium phosphate were added at 4 h, as indicated by an arrow. Elimination of 137Cs from the medium was determined by the silicone-oil-layer-centrifugation method, as described in “Materials and methods”. Final concentration of potassium (mg l−1): Closed circle 0 (control); triangle 1.25; diamond 2.5; ×-mark 5; square 10; open circle 25

Discussion

Global searches for strains with promising radionuclide elimination ability

We tested the ability of cells to accumulate/eliminate 137Cs, 85Sr and 125I from the medium among 188 strains of microalgae, aquatic plants, and colorless protists (Table S1; Fig. 2). We showed that algae and aquatic plants gradually absorb these radionuclides in a day-order time course (Fig. 3). We also showed that fresh water strains exhibited high ability for eliminating not only 137Cs, but also 85Sr and 125I (Table 1). Among the terrestrial algal strains, the multicellular filamentous cyanobacteria Nostoc commune TIR 4 and Scytonema javanicum NIES-1956 exhibited an especially high ability of I-elimination. However, we could find no marine strains which exhibit highly efficient elimination ability for the radionuclides in this study. This may be due to the presence of competitive elements in the seawater, such as potassium, calcium and non-radioactive iodine, which should decrease the efficiency of either absorption or accumulation of radionuclides by the cells. Colonial or multicellular strains had a tendency to eliminate 125I efficiently (Table 1, Table S1), although the mechanism remains unclear.

Heterotrophic organisms also showed lower uptake ability compared with autotrophic organisms (Fig. 3). This may also be related to the presence of physiological levels of potassium and calcium in the yeast extracts, which are supplemented to the growth medium for heterotrophs (Table S1).

When compared among various taxa, cyanobacteria, green algae and ochrophytes seem to exhibit higher radionuclide uptake ability than organisms in other taxa. This difference may be due to the presence of cell walls in these algal groups. However, rhodophytes, which also have a thick cell wall and mucoid substances, exhibited low radionuclide elimination ability, suggesting that the cell walls play a negative role against radionuclide uptake by the rhodophytes.

In our second tests for selected strains, five, three and eight strains showed high ability for eliminating 137Cs, 85Sr and 125I, respectively, from the medium (Table 1). Because these plants are easy to harvest and dry, they must be potentially useful to recover radioactive Cs from a huge volume of radio-polluted water.

Elimination of radioactive cesium

In our global searches, highly active strains for eliminating radioactive Cs, Sr and I are all fresh water strains. Cs, an alkali metal, is particularly known to be transported into cells as an analog of potassium. Therefore, the presence of potassium in the medium strongly disturbs the uptake of Cs (Bystrzejewska-Piotrowska and Urban 2003; Cline and Hungate 1960; Plato and Denovan 1974; Shaw 1993). For example, Cs uptake ability was reported to decrease by more than 80 % when 1.3 mM potassium was present in the medium with IC50 value of ca. 0.6 mM potassium (Plato and Denovan 1974). Such inhibition by potassium is confirmed in the present study. Radioactive Cs accumulation by the eustigmatophycean strain nak 9 was suppressed by potassium depending on the potassium concentration (Fig. 6). In fresh water, potassium concentrations are generally 0.5–3 mg l−1 and therefore the inhibition of Cs uptake by potassium should not be observed in the field. In contrast, seawater contains 390 mg l−1 potassium (Turekian 1968), and our results are consistent with a view that marine algae are unlikely to show an effective elimination ability for radioactive Cs.

In higher plants, sunflower has been reported to absorb 150 μg Cs in 100 h (Dushenkov et al. 1997), whereas a vetiver (Vetiveria zizanoides) absorbed 61 % of 137Cs in 168 h from radio-polluted water produced in the Chernobyl accident (Singh et al. 2009). In algae, the brown alga Laminaria digitata adsorbed more than 80 % of 134Cs under high pH conditions when the membrane was phosphorylated artificially (Pohl and Schimmack 2006). In this study, we found that the eustigmatophycean alga nak 9 could eliminate more than 90 % of radioactive Cs without any special treatment (Figs. 3, 4). The removal rate of 46.9 mg Cs kg DW−1 day−1 was very high (Figs. 3, 6). Therefore, we suspect that Cs is adsorbed on to the cell surface, although further study is needed to determine whether radioactive Cs is adsorbed by extra-cellular materials or absorbed into cells through the membrane (Figs. 3, 6).

Elimination of radioactive strontium

Strontium is known to accumulate in organisms and behave as an analog of calcium (Comar et al. 1957). In general, the elimination ability for radionuclides is believed to partly depend on the amount of gelatinous polysaccharide materials covering cell surface (Hill et al. 1997; Tamaru et al. 2005). Such extracellular polysaccharides have been reported to adsorb heavy metals. In the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, an extracellular hemolysin-like protein (HLP) conjugate with polysaccharides functions to adsorb 109Cd very rapidly (in a minute-order time course) (Sakiyama et al. 2011). In N. commune, the absorption of 85Sr into the cells is increased by phosphorylation on the cell surface (Pohl and Schimmack 2006). In terrestrial plants, sunflower is able to entirely absorb 150 μg Sr in 100 h when grown in radio-polluted water (Dushenkov et al. 1997). On the other hand, our results with algae and aquatic plants showed linier increase in elimination ability during time course (Fig. 3). These data suggest that 85Sr can be eliminated from the medium by absorption, but not by simple adsorption.

Elimination of radioactive iodine

We showed that the uptake ability of 125I is high in cyanobacteria, green algae (especially Chlorophyceae, Ulvophyceae, and streptophyte algae) and ochrophytes. The top three eliminators of 125I were cyanobacteria (Table 1; Figs. 2, 3). It is not yet well understood why many living organisms require iodine, although brown macroalgae contain high amounts of iodine in the fronds (Gall et al. 2004; Phaneuf et al. 1999). In some microalgae, iodine is known to accumulate in the cells, but the effects are diverse, i.e., it stimulates, suppresses or exerts no effect on the growth of marine microalgae depending on species (Iwamoto and Shiraiwa 2012). Iodine is absorbed by microalgal cells as iodide (I−) and iodate (IO3 −), the latter being predominant in seawater (Iwamoto and Shiraiwa 2012). In terrestrial plants, iodide is highly concentrated in the roots of Japanese mustard spinach (Muramatsu et al. 1983), and paddy-rice accumulates considerable amounts of 131I adsorbed from soil in the roots (Tensho and Yeh 1970).

Effect of potassium on radioactive cesium elimination by the strain nak 9

Figure 5 shows that Lemna aoukikusa (TIR 3), a floating vascular plant, is useful for the elimination of both radioactive Cs and I and that the cyanobacterium Stigonema ocellatum (NIES-2131) is useful for the removal of both Sr and I. Besides of these organisms, elimination ability of radioactive Cs, Sr and I is species-specific for each element. Radioactive Sr can be eliminated selectively by the chlorophycean alga Oedogonium sp. (nak 1001) and radioactive I can be eliminated by a chlorophycean vascular aquatic plant Elodea nuttallii (We 4) and an ulvophycean filamentous alga Rizochlonium sp. (nak 1002).

Future study

According to the TEPCO report, water polluted with radioactive Cs is continuously stored in the main facilities of F1NPP such as the nuclear reactor building and turbine building (TEPCO 2013). Reducing the amount of radio-polluted soils and water is an urgent task in our society. Therefore, biological concentration of radionuclides is an essential technology for bioremediation of the radio-polluted environment. In this study, we succeeded in identifying some microalgae, such as the eustigmatophycean strain nak 9, which are potentially useful for decontaminating radioactive Cs from highly radio-polluted water stored in the nuclear reactor building of F1NPP, or for reducing a volume of the radio-polluted water. However, in practical application of our strains to decontamination of mega volumes of radio-polluted water in F1NPP, further studies are required to develop a system that allows mass cultivation and efficient coagulation/sedimentation of algal strains. It is also important to find new strains that possess high ability to eliminate multiple radionuclides i.e. Cs, Sr and I from the medium.

It is also important to develop a method for solubilizing Cs from soil matrix. In the environment, such as river water, ponds and the sea surrounding the radiopolluted area, the radioactivity of radiopollutants released from the F1NPP was below a detectable limit (FA 2013). Furthermore, radioactive Cs has been reported to tightly bind to fine soil particles in shallow depth. Radioactive Cs is extremely difficult to extract from the sediment particles and needs to be treated with extremely strong acid for re-solubilizing. In order to use microalgae for eliminating radioactive Cs from the soil, we must first need to release Cs from the fine soil particles into aqueous solution. As one of possible methods, an electrokinetic method reported recently (Oguri et al. 2004) would be suitable for releasing such tightly bound Cs into water. In combination with such treatment, the usefulness of our microalgal phytoremediation must be enhanced by further studies on technological development under tight collaboration of scientists among different scientific disciplines.

References

Araie H, Sakamoto K, Suzuki I, Shiraiwa Y (2011) Characterization of the selenite uptake mechanism in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta). Plant Cell Physiol 52:1204–1210

Betsy A, Sudershan Rao V, Polasa K (2012) Evolution of approaches in conducting total diet studies. J Appl Toxicol 32:765–776

Bystrzejewska-Piotrowska G, Urban PL (2003) Accumulation of cesium in leaves of Lepidium sativum and its influence on photosynthesis and transpiration. Acta Biol Cracov Bot 45:131–137

Carolan JV, Hughes CE, Hoffmann EL (2011) Dose assessment for marine biota and humans from discharge of 131I to the marine environment and uptake by algae in Sydney, Australia. J Environ Radioactiv 102:953–963

Casacuberta N, Masqué P, Garcia-orellana J, Garcia-Tenorio R, Buessler KO (2013) 90Sr and 89Sr in seawater off Japan as a consequence of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Biogeosciences 10:3649–3659

Chino M, Nakayama H, Nagai H, Terada H, Katata G, Yonezawa H (2011) Preliminary estimation of release amount of 131I and 137Cs accidentally discharged from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the atmosphere. J Nucl Sci Tech 48:1129–1134

Chowdhury MJ, Blust R (2011) Strontium. In: Wood CM, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ (eds) Fish physiology 31B: homeostasis and toxicology of non-essential metals. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 351–390

Cline JF, Hungate FP (1960) Accumulation of potassium, cesium137, and rubidium66 in bean plants grown in nutrient solutions. Plant Physiol 35:826–829

Comar CL, Russell RS, Wasserman RH (1957) Strontium-calcium movement from soil to man. Science 126:485–492

Dubrova YE, Nesterov VN, Krouchinsky NG, Ostapenko VA, Neumann R, Neil DL, Jeffreys AJ (1996) Human mini-satellite mutation rate after the Chernobyl accident. Nature 380:683–686

Dushenkov S, Vasudev D, Kapulnik Y, Gleba D, Fleisher D, Ting KC, Ensley B (1997) Removal of uranium from water using terrestrial plants. Environ Sci Technol 31:3468–3474

Endo R, Kadokura H, Tanaka K, Ubukata S, Tsubura H, Ozaki Y (2013) Analysis of factors in absorption of radioactive caesium for processing tomatoes. Radioisotopes 62:275–280

Escher BI, Hermens JLM (2004) Peer reviewed: internal exposure: linking bioavailability to effects. Environ Sci Technol 38:455–462

FA (Fisheries Agency) (2013) Results of the inspection on radioactive materials in fisheries products (press releases in April, 2013). http://www.jfa.maff.go.jp/e/inspection/index.html

Fugazzola L, Pilotti S, Pinchera A, Vorontsova TV, Mondellini P, Bongarzone I, Greco A, Astakhova L, Butti MG, Demidchik EP, Pacini F, Marco A Pierotti MA (1995) Oncogenic rearrangements of the RET proto-oncogene in papillary thyroid carcinomas from children exposed to the Chernobyl nuclear accident. Can Res 55:5617–5620

Fukuda S, Yamakawa R, Hirai M, Kashino Y, Koike H, Satoh K (2008) Mechanisms to avoid photoinhibition in a desiccation-tolerant cyanobacterium, Nostoc commune. Plant Cell Physiol 49:488–492

Gall EA, Küpper FC, Kloareg B (2004) A survey of iodine content in Laminaria digitata. Bot Mar 47:30–37

Golikov V, Logacheva I, Bruk G, Shutov V, Balonov M, Strand P, Borghuis S, Howard B, Wright S (2004) Modelling of long-term behaviour of caesium and strontium radionuclides in the Arctic environment and human exposure. J Environ Radioactiv 74:159–169

Hill DR, Keenan TW, Helm RF, Potts M, Crowe LM, Crowe JH (1997) Extracellular polysaccharide of Nostoc commune (Cyanobacteria) inhibits fusion of membrane vesicles during desiccation. J Appl Physiol 9:237–248

Hosono Y, Takahashi H (2013) Radioactive contamination by the accident of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, and the transition of the radioactive concentration-measurement of the tea leaf etc. of Bunkyo-ku Hongo and Tokorozawa. Radioisotopes 62:21–25

IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) (2006) Radiological assessment reports series, Environmental consequence of the Chernobyl accident and their remediation, twenty years of experience, Report of the Chernobyl Forum Expert Group “Environment”

Iwamoto K, Shiraiwa Y (2012) Characterization of intracellular iodine accumulation by iodine-tolerant microalgae. Procedia Environ Sci 15:34–42

Kasai F, Kawachi M, Erata M, Watanabe MM (2004) NIES-collection: list of strains. Microalgae and protozoa, 7th edn. National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan, pp 49–58

Kawai H, Kitamura A, Mimura M, Mimura T, Tahara T, Aida D, Sato K, Sasaki H (2014) Radioactive cesium accumulation in seaweeds by the Fukushima 1 Nuclear Power Plant accident—two years’ monitoring at Iwaki and its vicinity. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0603-1

Kobayashi D, Okouchi T, Yamagami M, Shinano T (2014) Verification of radiocesium decontamination from farmlands by plants in Fukushima. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0607-x

Küpper FC, Schweigert N, Gall EA, Legendre JM, Vilter H, Kloareg B (1998) Iodine uptake in Laminariales involves extracellular, haloperoxidase-mediated oxidation of iodide. Planta 207:163–171

Liebhafsky HA, McGavock WC, Reyes RJ, Roe GM, Wu LS (1978) Reactions involving hydrogen peroxide, iodine, and iodate ion 6. Oxidation of iodine by hydrogen peroxide at 50 °C. J Am Chem Soc 100:87–91

Martinelango PK, Tian K, Dasgupta PK (2006) Perchlorate in seawater: bioconcentration of iodide and perchlorate by various seaweed species. Anal Chim Acta 567:100–107

Marzano FN, Fiori F, Jia G, Chiantore M (2000) Anthropogenic radionuclides bioaccumulation in antarctic marine fauna and its ecological relevance. Polar Biol 23:753–758

Mimura M, Kobayashi D, Komiyama C, Miyamoto M, Kitamura A, Mimura T (2014) Radioactive pollution and accumulation of radionuclides in wild plants in Fukushima. J Plant Res (in this issue)

Mück K (1997) Long-term effective decrease of cesium concentration in foodstuffs after nuclear fallout. Health Phys 72:659–673

Muramatsu Y, Christoffers D, Ohmomo Y (1983) Influence of chemical forms on iodine uptake by plant. J Rad Res 24:326–338

Nakanishi TM, Kobayashi NI, Tanoi K (2013) Radioactive cesium deposition on rice, wheat, peach tree and soil after nuclear accident in Fukushima. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 296:985–989

Nikiforov Y, Gnepp DR (1994) Pediatric thyroid cancer after the Chernobyl disaster. Pathomorphologic study of 84 cases (1991–1992) from the Republic of Belarus. Cancer 74:748–766

NISA (Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency) (2011) About the evaluation of the state of reactor core of No. 1, 2 and 3 concerning the accident of the Tokyo Electric Power Co., Inc. Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Press release on June 6 2011 (in Japanese)

Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters (2011) Report of Japanese government to the IAEA ministerial conference on nuclear safety -The accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Nuclear Power Stations-. http://www.kantei.go.jp/foreign/kan/topics/201106/iaea_houkokusho_e.html

Oguri Y, Miyake K, Fukuda H, Kaneko J, Hasagawa J, Ogawa M, Shiho M (2004) Application of PIXE analysis to the study of electrokinetic removal of cesium from soil. Int J PIXE 14:49–56

Ohmori Y, Kajikawa M, Nishida S, Tanaka N, Kobayashi NI, Tanoi K, Furukawa J, Fujiwara T (2014) The effect of fertilization on cesium concentration of rice grown in a paddy field in Fukushima Prefecture in 2011 and 2012. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0618-7

Phaneuf D, Cote I, Dumas P, Ferron LA, LeBlanc A (1999) Evaluation of the contamination of marine algae (seaweed) from the St. Lawrence River and likely to be consumed by humans. Environ Res 80:S175–S182

Plato P, Denovan JT (1974) The influence of potassium on the removal of 137Cs by live Chlorella from low level radioactive wastes. Rad Bot 14:37–41

Pohl P, Schimmack W (2006) Adsorption of radionuclides (134Cs, 85Sr, 226Ra, 241Am) by extracted biomasses of cyanobacteria (Nostoc carneum, N. insulare, Oscillatoria geminata and Spirulina laxissima) and Phaeophyceae (Laminaria digitata and L. japonica; waste products from alginate production) at different pH. J Appl Phycol 18:135–143

Polar E (2002) The association of 137Cs with various components of tea leaves fermented from Chernobyl contaminated green tea. J Environ Radioact 63:265–270

Rowan DJ, Rasmussen JB (1994) Bioaccumulation of radiocesium by fish: the influence of physicochemical factors and trophic structure. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 51:2388–2410

Sakiyama T, Araie H, Suzuki I, Shiraiwa Y (2011) Functions of a hemolysin-like protein in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Arch Microbiol 193:565–571

Sekimoto H, Yamada T, Hotsuki T, Fujiwara T, Mimura T, Matsuzaki A (2014) Evaluation of the radioactive Cs concentration in brown rice based on the K nutritional status of shoots. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0614-y

Shaw G (1993) Blockade by fertilisers of caesium and stronium uptake into crops: effects on the root uptake process. Sci Total Environ 137:119–133

Singh S, Thorat V, Kaushik CP, Raj K, Susan Eapen S, D’Souza SF (2009) Potential of Chromolaena odorata for phytoremediation of 137Cs from solution and low level nuclear waste. Ecotoxicol Environ 69:743–745

Stohl A, Seibert P, Wotawa G, Arnold D, Burkhart JF, Eckhardt S, Topia C, Vangas A, Yasunari TJ (2012) Xenon-133 and caesium-137 release into the atmosphere from the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power plant: determination of the source term, atmospheric dispersion, and deposition. Atmos Chem Phys 12:2313–2343

Tamaru Y, Takani Y, Yoshida T, Sakamoto T (2005) Crucial role of extracellular polysaccharides in desiccation and freezing tolerance in the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7327–7333

Tanoi K, Kobayashi NI, Ono U, Fujimura S, Nakanishi TM, Nemoto K (2013) Radiocaesium distribution in rice plants grown in the contaminated soil in Fukushima Prefecture in 2011. Radioisotopes 62:25–29

Tensho K, Yeh K (1970) Radio-iodine uptake by plant from soil with special reference to lowland rice. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 16:30–37

TEPCO (The Tokyo Electric Power Co., Inc.) (2012) About the estimation of the total amount of radioactive materials released to the atmosphere by the accident of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Press Release: 2012 (in Japanese)

TEPCO (The Tokyo Electric Power Co., Inc.) (2013) No. 92: about the present situation of storage and processing of water containing high concentration of radioactive compounds in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Press Release: 2013 (in Japanese)

Terashima I, Shiyomi M, Fukuda H (2014) 134Cs and 137Cs levels in a meadow, 32 km northwest of the Fukushima 1 Nuclear Power Plant, measured for two seasons after the fallout. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0608-9

Turekian KK (1968) Oceans. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, p 120

Yamashita J, Enomoto T, Yamada M, Ono T, Hanafusa T, Nagamatsu T, Sonoda S, Yamamoto Y (2014) Estimation of soil-to-plant transfer factors of radiocesium in 99 wild plant species grown in arable lands 1 year after the Fukushima 1 Nuclear Power Plant accident. J Plant Res 127 (in this issue). doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0605-z

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Makoto Shiho and all the members of the “Research Group on Decontamination of Radionuclide-polluted Water and Soils (office; University of Tsukuba, Japan)” for valuable contribution. This study was supported by grants-in-aid from the Strategic Funds for the Promotion of Science and Technology 2011: establishment of the measures platform to environmental influence with the radioactive material (Japanese Cabinet Office, Japan) and from the Great East Japan Earthquake Recovery and Rebirth Assistance Program in 2012 and 2013 (University of Tsukuba, Japan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

S. Fukuda, K. Iwamoto and M. Atsumi have contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuda, Sy., Iwamoto, K., Atsumi, M. et al. Global searches for microalgae and aquatic plants that can eliminate radioactive cesium, iodine and strontium from the radio-polluted aquatic environment: a bioremediation strategy. J Plant Res 127, 79–89 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-013-0596-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-013-0596-9