Abstract

The association between fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is of growing interest in psychosocial research. The mechanisms by which both disorders are interconnected are not well understood. The article presents an overview of the study results available on the prevalence of PTSD in FMS patients, the known and proposed mechanisms of their association, and the impact of PTSD on FMS outcomes. In addition, practical issues related to PTSD and FMS in clinical practice are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Fibromyalgia syndrome

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- Depression

- Catastrophizing

- Stress vulnerability

- Biopsychosocial model

Introduction

Definition of Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is characterized by chronic widespread pain which commonly coexists with cognitive dysfunction, sleep disturbance, and fatigue (Häuser et al. 2008; Wolfe et al. 2010): Most patients report a wide range of additional somatic and psychological symptoms. Lacking a specific laboratory test, clinical diagnosis can be based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 classification (Wolfe et al. 1990), the ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria (Wolfe et al. 2010), and the 2011 research criteria (Wolfe et al. 2011a; Wolfe 2014). The ACR 2010 preliminary diagnostic criteria and the research criteria require the exclusion of a medical disorder sufficiently explaining the symptoms. Patients commonly report increased disability, reduced health-related quality of life, and increased healthcare use. Many FMS patients extensively utilize healthcare (Haviland et al. 2010; Marschall et al. 2011; Knight et al. 2013). Depending on the number and severity of symptoms and the degree of disability, slight, moderate, and severe forms of FMS can be differentiated (Chandran et al. 2012; Häuser et al. 2014).

Controversies on FMS

FMS is a “bitterly controversial condition” (Wolfe 2009). Some of the FMS “wars” are fought between patients, rheumatologists, and pain specialists and experts in psychosocial medicine. Rheumatologists and pain scientists commonly conceptualize FMS as a central nervous system pain sensitivity syndrome (Clauw 2014). This view of FMS is contested by many psychiatrists and psychologists, who view FMS symptoms as part of somatoform or somatic symptom disorders, each with its own biological conceptualization (Häuser and Henningsen 2014).

Prevalence of FMS

FMS is a common disorder occurring in all populations across the world. Estimates of the prevalence of FMS according to the ACR 1990 classification criteria in the general European population range from 2.1 % to 2.9 % (Branco et al. 2010) and was 2.0 % in Wichita, USA (Wolfe et al. 1995). The prevalence of FMS according to the research criteria was 2.1 % in the general German (Wolfe et al. 2013) and Japanese population (Nakamura et al. 2014).

Etiology and Pathophysiology of FMS

A biopsychosocial model of factors predisposing to, triggering, and perpetuating FMS symptoms has been suggested (Sommer et al. 2012) (see Table 1).

Genes (Arnold et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2010), physical and sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence (Häuser et al. 2011), lifestyle factors (obesity, physical inactivity) (Mork et al. 2010), and sleep disturbances (Mork and Nilsen 2012) predispose to FMS. Psychological stress (e.g., working place conflicts), physical stress (e.g., uncomfortable postures at work such as crouching, repetitive movements of wrist, and monotonous work), as well as somatic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus) may trigger the development of chronic widespread pain (McBeth et al. 2003; Van Houdenhove et al. 2005; Wolfe et al. 2011b). If car accidents can trigger FMS symptoms in predisposed persons is under debate (Wolfe et al. 2014). Concomitant mental disorders, such as depressive disorders (Lange and Petermann 2010), have a negative impact on the clinical outcome of FMS.

Several biological differences in FMS patients compared to healthy controls have been observed (see Table 2).

Differences in structure and function of central pain pathways, diminished reactivity of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis to stressors, increased systemic proinflammatory and reduced anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles in serum, anatomic and avidity differences in dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, and decreases in small fiber density have been associated with the FMS phenotype. However, none of these factors/mechanisms have been demonstrated to be necessary or sufficient to cause or maintain FMS symptoms (Sommer et al. 2012; Üçeyler et al. 2013). The dominant modern pathophysiologic concept views FMS as the result of alterations in central pain processing, involving alteration of sensory input, increased cognitive–emotional appraisal, and reflexive amplification of future sensory input (Bradley 2009; Cagnie et al. 2014).

Prevalence of Traumatic Experiences in FMS Patients

Many case–control studies have been conducted regarding the association of major life events and childhood/adolescence adversities with adult FMS. A systematic review of case–control studies (FMS patients versus healthy controls or patients with other rheumatic diseases) found significant associations between FMS and self-reported physical abuse in childhood (OR 2.49 [95 % CI 1.81–3.42], I2 0 %; 9 studies) and adulthood (OR 3.07 [95 % CI 1.01–9.39], I2 79 %; 3 studies) and sexual abuse in childhood (OR 1.94 [95 % CI 1.36–2.75], I2 20 %; 10 studies) and adulthood (OR 2.24 [95 % CI 1.07–4.70], I2 64 %; 4 studies) (Häuser et al. 2011). The studies reviewed did not assess if the major life events and childhood adversities were experienced to be traumatic and if some of the patients met the criteria of PTSD.

The studies on the frequency of potentially traumatic experiences were conducted in different settings and used different instruments (see Table 3).

In the US Biopsychosocial Religion and Health Study, 10,424 subjects participated. Survey respondents that self-reported being diagnosed with FMS by a physician reported more frequently at least one life-threatening trauma (no further specification provided in the paper) than participants not reporting a FMS diagnosis (61.0 % vs. 57.4 %) (Haviland et al. 2010). In a single-center Dutch study, 82.0 % of 28 FMS patients and 61.0 % of 51 patients with rheumatoid arthritis reported at least one traumatic event (emotional or physical or sexual abuse) (Näring et al. 2007). In a single-center Israeli study, the most frequently reported traumatic events among FMS patients included the following: family violence (39.9 %), sudden unexpected death of close friend or relative (35 %), involvement in a serious motor vehicle accident (30.7 %), natural disaster (19.4 %), sexual assault (10.2 %), one’s child being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness (13.3 %), and being diagnosed with life-threatening illness (not FMS) (12 %). The authors did not include a control group (Cohen et al. 2002). In a German multicenter study of different settings (in- and outpatient, different specialties), 278 (70.3 %) out of 395 FMS patients reported at least one traumatic event. Sixty-nine out of 395 (17.5 %) of control individuals reported at least one traumatic event. In FMS patients, the worst traumatic experiences were “a terrible event not specified by the trauma list” (37.5 % of patients), witnessing a terrible event in another person (9.6 % of patients), and sexual abuse before 14 years of age (6.1 % of patients). In age- and sex-matched population controls, the worst traumatic experiences were witnessing a terrible event in another person (4.3 %), diagnosis of a life-threatening illness (3.5 %), and a “terrible event not specified by the trauma list” (2.8 %). FMS patients with PTSD reported other terrible life events (51.9 %), witnessing terrible life event in another person (15.1 %), sexual abuse < 14 years (9.5 %), severe physical violence (7.3 %), severe accidents, rape (each 3.4 %), war exposure, eviction (1.1 % each), and imprisonment (0.6 %) to have been the worst traumatic experience. Population controls with PTSD reported war exposure (8.3 %), severe physical violence (8.3 %), natural catastrophe (8.3 %), witnessing terrible life event in another person (8.3 %), diagnosis of life-threatening illness (16.6 %), other terrible life event (24.9 %), and sexual abuse < 14 years (24.9 %) to have been the worst traumatic experience (Häuser et al. 2013).

Prevalence of PTSD in FMS Patients

The prevalence of PTSD reported by different studies range from 8 % to 57 % (see Table 4).

Fifty-six percent of 39 FMS patients of one US pain medicine center reported clinically significant levels of PTSD symptoms (Sherman et al. 2000). Fifty-seven percent out of 77 FMS patients of one Israeli rheumatology department were diagnosed with PTSD (Cohen et al. 2002). In two community-based US studies, the prevalence of PTSD in 52 and 149 FMS patients was 27 % and 14 % (Raphael et al. 2004; Raphael et al. 2006). In a US referral clinic, the prevalence of lifetime PTSD was 20 % in patients with FMS and/or chronic fatigue syndrome (Roy-Bryne et al. 2004). In a German single-center rheumatology study with 115 FMS patients, 41 % reported PTSD symptoms in a questionnaire, and 8 % met the criteria of PTSD in a structured clinical interview (Thieme et al. 2004). The prevalence of PTSD in FMS was 45.3 % compared to 3.0 % in age- and sex-matched population controls in a German multicenter study (Häuser et al. 2013). In an Israeli single-center study, the prevalence of FMS in a group of 29 patients with PTSD was 21 % (compared to 0 % in a group of controls) (Amir et al. 1997). The differences in the prevalence rates can be explained by the different instruments and settings. The prevalence rates were higher in the case of a questionnaire-based diagnosis and lower in the case of clinical interview-based diagnosis of PTSD.

Mechanisms of the Association of FMS and PTSD

Overlap of FMS and PTSD symptoms: One potential reason why overlap is seen between FMS and PTSD is the obvious overlap in symptoms. Two symptoms of the D-criterion of PTSD, namely, sleeping and concentration problems, are main symptoms of FMS (Häuser et al. 2008; Wolfe et al. 2010, 2011a). The PTSD rate in the German multicenter study sample decreased from 45 % to 39 % after removing the sleeping and concentration problems and one additional depression item (loss of interest) from the algorithm of the PTSD (Häuser et al. 2013). In addition, the “symptom confounding hypothesis” of FMS and PTSD had been ruled out in a study of Raphael and coworkers (Raphael et al. 2004): In a telephone study of 1,312 women in metropolitan New York, FMS symptoms 6 months prior to the World Trade Center terrorist attacks predicted a threefold increase in PTSD afterwards.

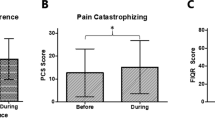

Catastrophizing: Catastrophizing is defined as a set of cognitive and emotional processes leading to a tendency to misinterpret and exaggerate situations that may be threatening (Edwards et al. 2006). In FMS, pain catastrophizing is a current major topic of psychological research. Pain-related catastrophizing is broadly conceived as a set of exaggerated and negative cognitive and emotional schema brought to bear during actual or anticipated painful stimulation. Pain catastrophizing shares significant variance with broader negative affect constructs, such as depression, anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, worry, and neuroticism (Quartana et al. 2009). Catastrophizing encompasses not only pain but also major life events in FMS patients (Häuser et al. 2013). In the German multicenter study, FMS patients assessed 290 out of 294 (98.6 %) major life events to be traumatic. One hundred and seventy-nine out of 290 (61.7 %) FMS patients who reported traumatic events met the criteria of a PTSD. In contrast, population controls retrospectively assessed 50 out of 75 (66.6 %) major life events to be traumatic. Twelve out of 50 (24 %) population controls who reported traumatic events met the criteria of a PTSD. FMS patients tend to experience chronic stress (e.g., working place conflicts) and major life events (e.g., loss of job) to be traumatic and report PTSD symptoms such as nightmares and hyperarousal related to these events which do not meet the criteria of a trauma from a clinician’s point of view (Häuser, unpublished data). These data support the view that PTSD represents a marker of stress vulnerability rather than a particular set of biological reactions caused by exposure to a trauma (Raphael et al. 2004).

The hypothesis of stress vulnerability of FMS patients was further affirmed by a longitudinal Japanese study which evaluated responses to traumatic stress and depression 1 month after an earthquake and every 6 months until 19 months after the disaster in healthy controls and rheumatoid arthritis and FMS patients. Although response to acute stress induced by the great earthquake was likely to be settled within 7 months after the disaster, depression-related symptoms increased for more than 1 year after the disaster in FMS patients, despite exclusion of patients with major depression at baseline. This long-lasting worsening of depression-related symptoms may have been in response to chronic stress induced by the fear of radiation due to the nuclear power disaster (Usui et al. 2013).

Depression: Affective disorders are frequent comorbidities of FMS (Fietta et al. 2007). Persons with a history of emotional neglect and sexual abuse were more likely to develop more than one lifetime affective disorder (Kessler et al. 2010). In addition, cognitive theories of depression emphasize a vicious circle between depressed mood and biased recall toward negative information. Depressed adults show selectively enhanced recall for negative information (Kuiper and Derry 1982). Therefore, the memory and retrospective evaluation of childhood events could be influenced by a depressive recall bias. Thus, the association between childhood mistreatment and adult FMS may be mediated by depressive disorders. A cross-sectional case series with 328 German FMS patients of different levels of care (Kosseva et al. 2010) and a cross-sectional population-based US study with 10,424 older women and men (11 with personal communication) (Haviland et al. 2010) found that FMS patients with depressive disorder reported more childhood mistreatment than FMS patients without depressive disorder. In a German two-center study, the scores of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire of 153 FMS patients and 153 age- and gender-matched participants of the general population were compared adjusted for depressed mood. Depressed mood fully accounted for group difference in physical abuse and in emotional neglect, partially accounted for group difference in emotional abuse but did not account for group difference in sexual abuse (Häuser et al. 2012a). To conclude, the association of FMS and PTSD is partially mediated by depression.

Common antecedent traumatic events: In the German multicenter study, 70.3 % of patients reported at least one traumatic event. In 66 % of these patients, traumatic life events preceded the onset of chronic widespread pain (CWP). In 30 % of these patients, traumatic life events and PTSD symptoms followed the onset of CWP. In 4 % of these patients, traumatic life events, PTSD symptoms, and CWP occurred in the same year (Häuser et al. 2013). These data further support the hypothesis that traumatic experiences and PTSD increase the risk of developing FMS (Raphael et al. 2004), as the majority of FMS patients with PTSD reported that CWP developed after both the traumatic event and the onset of PTSD symptoms. PTSD also moderated the relation between childhood victimization and pain 30 years later in a prospective follow-up of a cohort study of individuals with court-documented early childhood abuse/neglect (Raphael et al. 2006) and between traumatic experiences and CWP in a cross-sectional study with persons aged 60–85 years in a representative population sample (Häuser et al. 2012b). PTSD, but not major depressive disorder, mediated the relationship between rape and FMS in a community-based US sample (Ciccone et al. 2005). It appears likely that the particulars of major life events alone do not increase the risk of FMS but rather that the event is experienced to be traumatic.

Mutual risk factors: Thirty percent of FMS patients with PTSD reported that traumatic events and PTSD symptoms occurred subsequent to the onset of CWP and even after the diagnosis of FMS in a German multicenter study (Häuser et al. 2013). Such data demonstrates that trauma is not necessary or sufficient to cause FMS. Rather, FMS can be regarded as an additive burden that strained coping resources when confronted with life stress (Sharp and Harvey 2001).

PTSD is both a potential risk factor for developing FMS (Raphael et al. 2004) and vice versa (Raphael et al. 2004; Sharp and Harvey 2001). It seems plausible that the relationship between pain and PTSD is bidirectional. Pain can serve as a provocative traumatic stimulus for the development of PTSD, and the hyper arousal, stress intolerance, and selective attention typical of PTSD may exacerbate or perpetuate pain (Asmundson and Katz 2008; Sherman et al. 2000).

PTSD as a maker of stress vulnerability: An integrative biopsychosocial model that conceptualizes FMS as a stress disorder has been proposed (Van Houdenhove et al. 2005). PTSD can be viewed as a marker of stress vulnerability in which persons susceptible to stress are more likely to develop CWP and other health problems, including FMS, when a potential traumatic event occurs (Raphael et al. 2006).

Impact of PTSD and FMS Outcome

In a US single-center study with 39 FMS patients, PTSD-positive patients reported significantly greater levels of pain, emotional distress, life interference, and disability than did the patients without clinically significant levels of PTSD symptoms (PTSD negative) (Sherman et al. 2000). In a single-center Italian study, fatigue and reduced health-related quality of life were associated with PTSD symptoms in 70 FMS patients (Dell’Osso et al. 2011). In a German multicenter study including 395 patients, FMS patients with PTSD were more frequently without a job or on sick leave; reported more pain sites, more somatic and psychological distress, and more disability; and met more frequently the criteria of a potential depressive disorder than patients without PTSD (Häuser et al. 2013). Concomitant PTSD and FMS appear to be more severe than FMS alone.

Practice and Procedures

Subgrouping FMS Patients

FMS is a clinically and probably biologically heterogeneous condition. The need to define subgroups to tailor treatment has been suggested by several research groups (de Souza et al. 2009; Docampo et al. 2013; Thieme et al. 2004). Similar approaches to subgroup FMS patients by comorbid mental disorder have been previously used to define study groups (Scheidt et al. 2013; McIntyre et al. 2014). However, there is no evidence that such tailored therapeutic approach would be more successful than current community standards.

Screening for PTSD in FMS Patients

Screening for mental disorders including PTSD in patients with FMS by primary care physicians, pain specialists, and rheumatologists after establishing the initial diagnosis has been recommended. Screening-positive patients should be referred to mental healthcare specialists for further evaluation (Köllner et al. 2012). Traumatic events should only be explored in the case of PTSD symptoms because therapeutic procedures can lead to false memories and individual vulnerability to resisting false memories (Loftus and Davis 2006).

Therapeutic Approaches

To date, the standard treatment approach for PTSD–FMS patients is to individually address both PTSD and FMS symptoms. When available, patients should be referred to multidisciplinary treatment programs targeting both disorders.

There are no current guidelines that detail the best practices for treating PTSD–FMS patients. Integrated treatment programs for PTSD and chronic pain are available (Bosco et al. 2013; Otis et al. 2009; Plagge et al. 2013) but have not been tested in FMS patients. While tailored psychological therapies for PTSD–FMS patients have not yet been studied, future trials should be compared to standard cognitive–behavioral pain therapy (Lumley 2011).

Prevention of future FMS in PTSD patients was the goal of one Israeli study. Physical exercise in 55 male patients with combat-related PTSD provided protection from the future development of fibromyalgia. Furthermore, physical activity was related in this group of patients to a better perception of their quality of life (Arnson et al. 2007).

Key Facts of Fibromyalgia Syndrome

FMS is characterized by chronic widespread pain, fatigue, and sleep problems in the absence of an identifiable medical disease or injury sufficiently explaining the symptoms.

Although the term “fibromyalgia” was first coined in 1976, physicians have written about conditions resembling FMS since the early 1800s. The illness “neurasthenia” (1860–1920) which was characterized by fatigue, pain, and mental confusion is one example.

Fibromyalgia has been recognized as a diagnosable disorder by the 1990 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) listed fibromyalgia as a diagnosable disease under “Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue” in 1994.

The diagnostic label “fibromyalgia” is contested by many psychiatrists and psychologists who diagnose patients with FMS symptoms with either somatoform disorder or somatic symptom disorder.

FMS is a common disorder occurring in all populations across the world. Estimates of the prevalence of FMS range from 2.1 % to 2.9 %.

A biopsychosocial model of factors predisposing to, triggering, and perpetuating FMS symptoms has been suggested.

FMS is the result of alterations in central pain processing, involving alteration of sensory input, increased cognitive–emotional appraisal, and reflexive amplification of future sensory input.

Summary Points

This chapter focuses on the prevalence of PTSD in FMS patients, the known and the proposed mechanisms of their association and the impact of PTSD on FMS outcome.

There is a wide range (8 %–57 %) of PTSD diagnosis in FMS patients that reflects important differences in study design.

The association of FMS and PTSD can be explained by symptom overlap between FMS and PTSD, coexisting depressive disorder, catastrophizing of FMS patients, and common antecedent traumatic experiences.

PTSD is a potential risk factor of FMS and vice versa. The relationship between chronic pain and PTSD symptoms is bidirectional: Pain can serve as a provocative traumatic stimulus for the development of PTSD, and the hyper arousal, stress intolerance, and selective attention typical of PTSD may exacerbate pain.

PTSD symptoms are a marker of stress vulnerability in FMS patients.

FMS patients with PTSD report more severe symptoms and greater disability than FMS patients without PTSD.

If the diagnosis of FMS is established for the first time, patients should be screened for comorbid mental disorders including PTSD.

Tailored psychotherapeutic and drug treatments for FMS patients with PTSD should be developed. When available, patients should be referred to multidisciplinary treatments programs targeting both disorders.

Abbreviations

- FMS:

-

Fibromyalgia syndrome

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

References

Amir M, Kaplan Z, Neumann L, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, tenderness and fibromyalgia. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:607–13.

Arnold LM, Fan J, Russell IJ, et al. The fibromyalgia family study: a genome-wide linkage scan study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1122–8.

Arnson Y, Amital D, Fostick L, et al. Physical activity protects male patients with post-traumatic stress disorder from developing severe fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(4):529–33.

Asmundson GJ, Katz J. Understanding pain and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity: do pathological responses to trauma alter the perception of pain? Pain. 2008;138(2):247–9.

Bosco MA, Gallinati JL, Clark ME. Conceptualizing and treating comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Pain Res Treat. 2013;2013:1–10.

Bradley LA. Pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2009;122(12 Suppl):S22–30.

Branco JC, Bannwarth B, Failde I, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a survey in five European countries. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(6):448–53.

Cagnie B, Coppieters I, Denecker S, et al. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain MRI. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(1):68–75.

Chandran A, Schaefer C, Ryan K, et al. The comparative economic burden of mild, moderate, and severe fibromyalgia: results from a retrospective chart review and cross-sectional survey of working-age U.S. adults. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(6):415–26.

Ciccone DS, Elliott DK, Chandler HK, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with fibromyalgia syndrome: a test of the trauma hypothesis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(5):378–86.

Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1547–55.

Cohen H, Neumann L, Haiman Y, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia patients: overlapping syndromes or post-traumatic fibromyalgia syndrome? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32(1):38–50.

de Souza JB, Goffaux P, Julien N, et al. Fibromyalgia subgroups: profiling distinct subgroups using the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. A preliminary study. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29(5):509–15.

Dell’Osso L, Carmassi C, Consoli G, et al. Lifetime post-traumatic stress symptoms are related to the health-related quality of life and severity of pain/fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(6 Suppl 69):S73–8.

Docampo E, Collado A, Escaramís G, et al. Cluster analysis of clinical data identifies fibromyalgia subgroups. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74873.

Edwards RR, Bingham 3rd CO, Bathon J, et al. Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):325–32.

Fietta P, Fietta P, Manganelli P. Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. Acta Biomed. 2007;78:88–95.

Häuser W, Henningsen P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: a somatoform disorder? Eur J Pain. 2014;18(8):1052–9.

Häuser W, Zimmer C, Felde E, et al. What are the key symptoms of fibromyalgia? Results of a survey of the German Fibromyalgia Association. Schmerz. 2008;22(2):176–83, German.

Häuser W, Kosseva M, Üceyler N, et al. Emotional, physical, and sexual abuse in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(6):808–20.

Häuser W, Bohn D, Kühn-Becker H, et al. Is the association of self-reported childhood maltreatments and adult fibromyalgia syndrome attributable to depression? A case control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012a;30(6 Suppl 74):59–64.

Häuser W, Glaesmer H, Schmutzer G, et al. Widespread pain in older Germans is associated with posttraumatic stress disorder and lifetime employment status–results of a cross-sectional survey with a representative population sample. Pain. 2012b;153(12):2466–72.

Häuser W, Galek A, Erbslöh-Möller B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia syndrome: prevalence, temporal relationship between posttraumatic stress and fibromyalgia symptoms, and impact on clinical outcome. Pain. 2013;154:1216–23.

Häuser W, Brähler E, Wolfe F, et al. Patient health questionnaire 15 as a generic measure of severity in fibromyalgia syndrome: surveys with patients of three different settings. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(4):307–11.

Haviland MG, Morton KR, Oda K, Fraser GE. Traumatic experiences, major life stressors, and self-reporting a physician-given fibromyalgia diagnosis. Psychiatry Res 2010; 177(3):335–41.

Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–85.

Knight T, Schaefer C, Chandran A, et al. Health-resource use and costs associated with fibromyalgia in France, Germany, and the United States. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:171–80.

Köllner V, Häuser W, Klimczyk K, et al. Psychotherapy for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline. Schmerz. 2012;26(3):291–6.

Kosseva M, Schild S, Wilhelm-Schwenk R, et al. Comorbid depression mediates the association of childhood/adolescent maltreatment and fibromyalgia syndrome. A study with patients from different clinical settings. Schmerz. 2010;24(5):474–84.

Kuiper NA, Derry PA. Depressed and nondepressed content self-reference in mild depressives. J Pers. 1982;50(1):67–80.

Lange M, Petermann F. Influence of depression on fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Schmerz. 2010;24:326–33.

Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Candidate gene studies of fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2010;32:417–26.

Loftus EF, Davis D. Recovered memories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:469–98.

Lumley MA. Beyond cognitive-behavioral therapy for fibromyalgia: addressing stress by emotional exposure, processing, and resolution. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(6):136.

Marschall U, Arnold B, Häuser W. Treatment and healthcare costs of fibromyalgia syndrome in Germany: analysis of the data of the Barmer health insurance (BEK) from 2008–2009. Schmerz. 2011;25(4):402–4, 406–10.

McBeth J, Harkness EF, Silman AJ, et al. The role of workplace low-level mechanical trauma, posture and environment in the onset of chronic widespread pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1486–94.

McIntyre A, Paisley D, Kouassi E, et al. Quetiapine fumarate extended-release for the treatment of major depression with comorbid fibromyalgia syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):451–61.

Mork PJ, Nilsen T. Sleep problems and risk of fibromyalgia: longitudinal data on an adult female population in Norway. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:281–4.

Mork PJ, Vasseljen O, Nilsen TI. Association between physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of fibromyalgia: longitudinal data from the Norwegian Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:611–7.

Nakamura I, Nishioka K, Usui C, et al. An epidemiological internet survey of fibromyalgia and chronic pain in Japan. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(7):1093–101.

Näring GW, van Lankveld W, Geenen R. Somatoform dissociation and traumatic experiences in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25(6):872–7.

Otis JD, Keane TM, Kerns RD, et al. The development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2009;10:1300.

Plagge JM, Lu MW, Lovejoy TI, et al. Treatment of comorbid pain and PTSD in returning veterans: a collaborative approach utilizing behavioral activation. Pain Med. 2013;14:1164–72.

Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(5):745–58.

Raphael KG, Janal MN, Nayak S. Comorbidity of fibromyalgia and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of women. Pain Med. 2004;5(1):33–41.

Raphael KG, Janal MN, Nayak S, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in a community sample of women with fibromyalgia. Pain. 2006;124(1–2):117–25.

Roy-Byrne P, Smith WR, Goldberg J, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among patients with chronic pain and chronic fatigue. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):363–8.

Scheidt CE, Waller E, Endorf K, et al. Is brief psychodynamic psychotherapy in primary fibromyalgia syndrome with concurrent depression an effective treatment? A randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(2):160–7.

Sharp TJ, Harvey AG. Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(6):857–77.

Sherman JJ, Turk DC, Okifuji A. Prevalence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms on patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(2):127–34.

Sommer C, Häuser W, Burgmer M, et al. Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome. Schmerz. 2012;26:259–67.

Thieme K, Turk DC, Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variables. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):837–44.

Üçeyler N, Zeller D, Kahn AK, et al. Small fibre pathology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Brain. 2013;136:1857–67.

Usui C, Hatta K, Aratani S, et al. Vulnerability to traumatic stress in fibromyalgia patients: 19 month follow-up after the great East Japan disaster. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R130.

Van Houdenhove B, Egle U, Luyten P. The role of life stress in fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:365–70.

Wolfe F. Fibromyalgia wars. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(4):671–8.

Wolfe F. Fibromyalgia research criteria. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(1):187.

Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria, for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(12):1863–4.

Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, et al. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19–25.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):600–10.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011a;38:1113–22.

Wolfe F, Häuser W, Hassett AL, et al. The development of fibromyalgia–I: examination of rates and predictors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Pain. 2011b;152:291–9.

Wolfe F, Brähler E, Hinz A, et al. Fibromyalgia prevalence, somatic symptom reporting, and the dimensionality of polysymptomatic distress: results from a survey of the general population. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:777–85.

Wolfe F, Häuser W, Walitt BT, et al. Fibromyalgia and physical trauma: the concepts we invent. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(9):1737–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry

Häuser, W., Ablin, J., Walitt, B. (2016). PTSD and Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Focus on Prevalence, Mechanisms, and Impact. In: Martin, C., Preedy, V., Patel, V. (eds) Comprehensive Guide to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08359-9_52

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08359-9_52

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08358-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08359-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences