Abstract

Climate change adaptation entails exploiting not only economically but also environmentally beneficial strategies by all stakeholders. However, the successful implementation of adaptation actions is also subject to the perception of climate change, usually influenced by knowledge, experiences, and sociocultural factors including gender relations, among the target group. This paper analyzes the perception of climate change among rural households in Southwest Nigeria and ascertains the coping and adaptation strategies in use among the households. A total of 239 respondents were interviewed across the vegetative zones available in the study area. Findings revealed that 54.8% were involved in crop farming. About 51.0% and 45.6% practiced change in sowing date and harvest date, respectively. Respondents’ perception had a significant relationship with adaptation measures such as change in harvest date (χ2 = 56.753, p = 0.026), planting improved varieties (χ2 = 55.866, p = 0.031), and mixed cropping (χ2 = 55.433, p = 0.042). Respondents had a favorable perception of climate change. The study concluded that although their perception of climate change was favorable and indicated their understanding of its negative effects on their livelihoods, it did not take cognizance of women’s insecure access to production resources. It recommended the development of easily accessible weather forecasts to aid livelihood decisions and enlightenment on improved women’s access to production resources and biodiversity protection.

This chapter was previously published non-open access with exclusive rights reserved by the Publisher. It has been changed retrospectively to open access under a CC BY 4.0 license and the copyright holder is “The Author(s)”. For further details, please see the license information at the end of the chapter.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Rural livelihoods comprise a diversity of capabilities, assets, and activities that rural people, households, and communities require to earn and secure their living (FAO 2003). Climate change threatens and erodes these assets, thereby hampering income generation and perpetuating poverty (IPCC 2007). However, the successful implementation of climate change adaptation strategies, which are essential to adjusting and reducing its negative impacts on food security, is influenced by rural households’ perception of climate change (Apurba and Haque 2017).

In developing countries, climate change is occurring in the midst of other developmental stressors, such as poverty, fluctuating oil prices, and land degradation. Adaptation strategies are aimed at lowering the vulnerability of natural and human systems to climate change so as not to frustrate food security and poverty reduction efforts (Bhatasara and Nyamwanza 2017). Due to its effect in slowing down economic growth, national governments have integrated climate change adaptation measures into their policy frameworks. At the local level, households adopt diverse strategies in their livelihoods to cope with climate change. They include change in planting date, livelihood diversification, borrowing, zero tillage, rationing, afforestation, planting improved crop varieties, and sale of assets, such as livestock (Akinbami et al. 2016; Abdulai et al. 2017). In the face of climate change, the survival of rural livelihoods is facilitated by adaptation strategies as they ensure

-

(i)

Food security

-

(ii)

A more reliable income flow for the welfare of households

However, as Agyei (2016) pointed out, the question of the sustainability of adaptation strategies must be answered before they are pursued. More important to the achievement of sustainable adaptation frameworks are the barriers to their implementation, including sociocultural barriers (Antwi-Agyei et al. 2014). Sociocultural barriers could stem from the values, beliefs, and norms of people. These factors shape their perception of climate change – a vital element that determines the adoption of sustainable adaptation strategies (Yaro 2006; Moser and Ekstrom 2010). Perceptions are gaining more recognition in climate change and adaptation studies because past experiences, observations, and future expectations of rural households may influence the choice of adaptation strategy employed to address climate change impacts (Maddison 2007).

Perceptions have been found to be one of the factors driving the choice of adaptation and mitigation strategies, thereby necessitating its integration in the design and development of climate-smart interventions for rural livelihoods, particularly agriculture (Grimberg et al. 2018). Five general classes of impediments to adaptation have been identified. They are financial, technological, cognitive, cultural, and institutional impediments. Local adaptive capacity recognizes not only the capitals and the resource-based components of adaptive capacity at local levels but also the intangible and dynamic factors such as perception (Jones et al. 2017). Rural livelihoods become more resilient when households are able to perceive first, the impacts of climate change, as well those of inappropriate adaptation measures (Alam et al. 2017). The study therefore aims to assess the perception of climate change among rural households in order to achieve sustainable climate adaptation.

Assessing perception of climate change among rural households will provide household-level data to aid the understanding of their resource exploitation behavior, capabilities, and challenges. In this way, local, context-specific sustainable adaption policies can be developed in order to address climate change issues and the interrelationship between livelihoods and gender concerns in rural areas. The study, therefore, aimed to ascertain the coping and adaptation strategies employed by rural households in their livelihoods and determine their perception of climate change.

Literature Review

Sustainable Climate Change Adaptation

Sustainable climate change adaptation entails the exploitation of available resources to meet present needs without jeopardizing the ability to meet future needs. It facilitates the pursuit of profitable livelihoods in a healthy environment. It, therefore, requires that rural households first become aware that climate change is real, understand the dynamic causes, and recognize available valuable adaptation strategies that are not only economically but also environmentally friendly before successful implementation can be achieved (Osumanu et al. 2017). If rural livelihoods are to recover from stresses and shocks while also sustaining their capabilities and assets without compromising the natural resource base, rural households must recognize that certain adaptation choices are capable of creating more harm than benefits in the long run (Bhatasara and Nyamwanza 2017).

The Concept of Perception in Climate Change Adaptation

Perception is formed from the combination of small bits of information about the environment and creating a duplicate internal representation. Perception refers to an individual’s or group’s unique way of viewing a phenomenon. It involves the processing of stimuli, memories, and experiences in the process of understanding. This highlights the three essential features of perception: (i) a sensory or cognition of the experience, (ii) personal experiences that help in interpreting and understanding a phenomenon, and (iii) comprehension that can lead to a response (Galotti 1994; McDonald 2012).

In relating perceptions to adaptation, studies (Asrat and Simane 2018; Zoundji et al. 2017; Ndamani and Watanabe 2015) have shown that as perception is dynamic, so is adaptation location-specific and influenced by key drivers such as socioeconomic, environmental, and institutional factors. Observations produce knowledge. Perceptions are interpretation of observations in connection to existing knowledge. Perceptions (of the effects of a chosen adaptation strategy) can combine with existing knowledge to produce adjusted or new action. However, before adaption action takes place, people must first perceive the reality of climate change and its impacts (Asrat and Simane 2018; Alam et al. 2017).

Description of the Study Areas and Methodology

Study Area

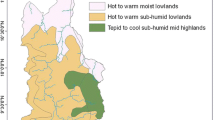

The study was conducted in the Southwest of Nigeria in 2018. Southwest Nigeria (also referred to as the Southwest geopolitical zone) has been experiencing intense dynamics of rapid socioeconomic development, land use, and population growth. It is made up of six states – Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, and Oyo. The area lies between longitude 2° 31ǀ and 6° 00ǀ East and latitude 6° 21ǀ and 8° 37ǀ North. It has a surface area of about 78,505 km2, population of 17,455,052 people, and a population density of 353 persons/km2 (NPC 2006). It is bound in the east by Edo and Delta states, in the north by Kwara and Kogi states, in the west by the Republic of Benin, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean (Faleyimu et al. 2010).

The climate of Southwest Nigeria is tropical in nature and is characterized by wet and dry seasons (Faleyimu et al. 2010). The dry season is short, lasting generally from December to February. The average annual rainfall is 1,200–1,500 mm. The monthly mean temperature ranges from about 22.49 °C to 31.24 °C, while the average annual temperature is about 26.6 °C. Furthermore, temperature is relatively high during the dry season and low during the rainy season, especially between July and August (Oyinloye and Oloukoi 2013). The average annual relative humidity is about 76.05%. The relatively high rainfall usually precipitates widespread flooding in some parts of the region. However, the indiscriminate exploitation of the environment has contributed to recent flood events.

There are three main types of vegetation in the region – mangrove forest which is found mainly in Lagos state and some parts of Ogun and Ondo states; tropical rain forest which is found mainly in Ogun, Ondo, Ekiti, and some parts of Oyo state; and, lastly, guinea and derived savanna found mainly in Osun and some parts of Oyo and Ogun states. Most of the rivers are short, north-south coastal rivers. The major rivers include Ogbese, Ogun, Ogunpa, Oluwa, Ominla, Oni, and Owena (Oyinloye and Oloukoi 2013).

The predominant economic activities are farming, trading, and artisanship. The climate favors the propagation of crops like yam, cassava, rice, plantains, cocoa, kola nut, oil palm, and maize, among others. As a result, majority of the inhabitants are farmers who practice farming enterprises ranging from crop production, livestock breeding, forestry practices, fisheries and aquaculture to agricultural processing (NPC 2006).

Research Methods

Study Site Selection and Sampling Methods

Lagos, Ondo, and Oyo states were purposively selected to represent the vegetation zones in the study area – Lagos (mangrove and coastal swamp), Oyo (rainforest and derived savanna), and Ondo (rainforest and coastal). The research was conducted in Badagry, Epe, Akure North, Eseodo, Ifedore, Ilaje, and Ibarapa Central and Ibarapa North local government areas (LGAs). Five communities were randomly selected from each LGA to yield a total of 40 communities. A random selection of 6 households from each of the 40 communities gave 240 households. In-depth interview with 16 community key informants was carried out. Key informant selection and interviews were carried out in consultation with enumerators and community members.

Data Sources and Collection Methods

The study utilized both quantitative and qualitative data. These were gathered from household heads through interview schedule and questionnaire survey as well as interviews for key informants. Data on local coping and adaptation strategies employed by the households were obtained using the survey. Data on perception were obtained using Likert-type scale items. Interviews with key informants and overt observation provided information on nature of farming and other livelihood activities, local gender dimensions, climate change impacts in the communities, coping strategies employed, and underlying social challenges.

Data Analysis

Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used in analyzing the coping and adaptation strategies employed by the households and their perception of climate change. SPSS was used to analyze quantitative data. A chi-square analysis was carried out to determine if there was a relationship between the perception of the rural households and their choice of coping and adaptation strategies. The mean of the perception statements was used. Analysis of qualitative data was done in the context of interview themes.

Results and Discussion

While the study sought to elicit information from both male-headed and female-headed households in order to disaggregate data on gender basis, there was inadequate female-headed household sample size. Moreover, some of the women were unwilling to be interviewed due to their gender roles of cooking for the household and childcare. As a result, male-headed households made up most of the sample. Although 240 respondents were intended for the study, information was obtained from 239.

Primary Livelihoods of Rural Households

As is typical of rural communities, Southwest Nigeria is agrarian in nature. Many households are involved in agriculture for both family consumption and income generation. However, nonfarm livelihoods are nonetheless important. Some of these livelihoods are agro-allied in nature, e.g., processing and trading of farm produce. Table 1 displays the livelihoods of the rural households.

Many of the households were involved in crop farming as it was the primary livelihood source for 54.8% of the households. This was followed by trading/business as approved by 14.6% of the households. Fishing ranked third as 10.9% of the households claimed it was their primary source of livelihood. Both processing and artisanship ranked fourth because 6.3% each of the respondents claimed either was their main source of livelihood. Gathering of non-timber forest products accounted for 1.7% of the respondents. Only 0.8% claimed hunting was their main source of livelihood.

Interviews with key informants and observations revealed that many of the households were smallholder farmers (average farm size >3.0 ha) involved mainly in maize, yam, cassava, plantain, oil palm, and cocoa. Farmers in the coastal areas were also involved in rice and coconut production. Animal husbandry, although widespread, was mainly for family consumption and for sale to maintain the welfare of the household during periods of hardship. Animals reared include goat, sheep, poultry, and, in some cases, pigs. Although fishing was the main source of livelihood in coastal areas, some households were involved in fish farming (aquaculture). Households involved in trading sold consumer goods which community members would have had to travel to more urbanized centers to buy.

Agriculture is the backbone of many rural economies, ensuring food security, employment, export earnings, and economic development. As Olajide et al. (2012) attested, it employs about 65% of the labor force in Nigeria, while contribution to GDP oscillates between 30% and 42%. However, as revealed by the study, it is worthy of note that the rural sector comprises a diversity of livelihoods and the players range from large and smallholder landlords, landless workers, fishing communities, nonagricultural entrepreneurs including artisans, public institutions, private firms, providers of inputs and services, farmers’ organizations, and nongovernmental organizations. Building sustainable and resilient rural livelihoods will, therefore, require that this wide array of stakeholders be given recognition in development initiatives and plans (FAO 2003).

Climate Change Coping and Adaptation Strategies Employed in Rural Livelihoods

Rural households make adaptation choices to cope with the effect of climate change. Many factors influence the coping and adaptation choices adopted by rural households in the pursuit of their livelihoods. Whether these choices augur well for profitable livelihoods and a healthy environment is also another challenge addressed by factors such as their level of exposure and awareness, education, income, and cultural affiliation. Table 2 displays the adaptation choices employed by the households in order to ensure thriving enterprises.

Of all the coping and adaptation strategies, strategies 4, 12, and 13 cannot be regarded as sustainable. Low incomes are a peculiarity of rural areas, and purchasing extra feed for livestock in the dry season will only add to the pressure on their meager earnings. Rural households engage in sale of assets to obtain cash to offset pressing needs. More often than not, rural households lack the required collateral to secure loans from commercial banks. Consequently, they resorted to borrowing. These measures are maladaptive and unsustainable as they erode efforts at food security and poverty reduction. They borrowed from relatives, friends, and credit groups such as esusu (informal savings group for mutual access to credit) and farmers’ groups. As buttressed by CARE (2011), these actions may appear to have immediate effect in managing crisis; they bear potential negative impacts on households’ asset base, health, local biodiversity, and ecosystem. However, groups such as esusu and farmers’ group can be veritable tools and platforms for improving welfare and achieving poverty reduction among rural households when provided operational resources and capacity.

About 51.0% and 45.6% of the respondents changed sowing and harvest dates, respectively, based on indigenous knowledge and personal observation of weather patterns and climate change impacts. This helped to minimize crop losses. Mixed cropping (45.2%), planting of improved varieties (34.3%), and afforestation (34.3%) were carried out to reduce risk. Mixed cropping serves as a buffer against weather fluctuation and an insurance against crop failure. Households involved in afforestation were those that had orange and kola nut trees. Tree planting was not widespread except for those that planted Gmelina arborea. These adaptation measures are encouraged by agricultural extension because they aid nutrient cycling, improved soil structure, and more reliable income stream. This result is in line with Asrat and Simane (2018) that adaptation strategies such as use of improved varieties and adjusting planting date were favored among farmers and also highlighted the role of extension in sustainable adaptation.

About 11.7% of them utilized weather forecasting services through electronic media in their livelihoods. The ISKA weather forecast service by GIZ is one of such platforms accessed through the mobile phone by respondents in Oyo state. This way, rural households are able to obtain climate information at affordable rates. Such platforms are useful in disaster risk management in developing early warning systems and preparedness of rural households (Antwi-Agyei et al. 2014). They promote the development of more resilient livelihoods.

Occasionally, support is mobilized for the household in form of money, labor, and materials by the community. This safety net is also badly affected by climate change impacts such as flooding, pest infestation and drought. Climate change makes it difficult to garner resources to help households in the community when there is a widespread effect (CARE 2011). Irrigation was employed by 32.6% and 17.6% resorted to seasonal migration. Usually, the irrigation practiced involved fetching water into watering cans from nearby streams to water farms during the dry season. This is because of the high cost of irrigation technology which smallholders cannot afford. Since agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa is basically rain-fed, poor access to irrigation limits production, impairing food production and income generation during dry season and drought. Moreover, the labor required to water the farms places extra strain on the time, energy, and health of household members. Members of rural households migrate in search of employment opportunities on a seasonal basis in order to augment income. However, increasing migration of men from rural areas in search of employment has caused the number of female-headed households to grow substantially (Omonona 2009; Gebre et al. 2019).

Households who obtained aid (such as money and implements) from government constituted 13.8%, while the use of organic manure was adopted by 29.3%. The use of organic manure is made easier where animals are being reared and crop residue can be utilized. Livelihood diversification (36.0%) was done to earn more income, especially into nonfarm or off-farm activities, such as artisanship (Loison 2015). This helps to increase income flow for the households. Construction of barriers and drainage channels was done in the coastal areas. Interview with key informants revealed that barriers were constructed usually by those involved in fish farming in the coastal areas to prevent their fish from being washed away by coastal flooding which could occur as a result of heavy rainfall.

Increased watering of plants prevents them from drying up or wilting which affects fruiting and, consequently, yield. Increased watering of livestock during hot weather reduces the incidence of heat stress among the animals so as not to affect their productivity. Fuel conservation reduces the rate of greenhouse gas emissions.

Table 2 also shows that respondents utilized more of coping and adaptation options that were affordable and easily accessible to them. The strategies include change in sowing and harvest dates, mixed cropping, afforestation, planting improved varieties, irrigation, and diversification of livelihoods. These strategies that come at little or no cost are favored by many rural households (Alam et al. 2017). For instance, household members assisted in fetching water from nearby streams to water farms.

Perception of Climate Change Among Rural Households

The belief system of rural households influences their adaptation choices and could either hinder or aid the implementation of sustainable adaptation strategies, especially at the local level. Like any other phenomenon, their understanding or opinion of climate change is shaped by their values, morals, and norms (culture), experiences, indigenous knowledge, education, exposure, opinion leaders in the community, and other factors. Table 3 reveals the opinions of the households as regards climate change.

Respondents agreed to statements 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 14, and 15. They disagreed with statements 1, 7, 9, 11, 12, and 13. They were undecided about statement 2. Respondents agreed that the protection of biodiversity is impossible with climate change. This is one of the reasons that make rural households opt for unsustainable adaptation choices that jeopardize their livelihoods and environmental sustainability (Osumanu et al. 2017). They agreed that increasing temperatures caused a decrease in their productivity and planting improved varieties could help minimize crop losses. High temperatures, an indicator of global warming, could affect health and cause household members to spend less time on their livelihoods. Improved varieties can withstand harsh weather conditions and still give good yield. They agreed that accumulation of livelihood assets has become much more difficult with climate change. This is because climate change erodes their effort at income generation, food security, and poverty reduction.

They also agreed that local or indigenous knowledge is useful in reinforcing scientific climate information to make it more relevant to rural livelihoods. Local experiences employed in coping with climate change can be integrated with scientific climate knowledge to improve its acceptability and adoption. They agreed that women are vulnerable to climate change due to their insecure access to production resources. They agreed that rampant bush burning in preparation for land cultivation has a negative effect on the environment. This knowledge may be due to their contact with agricultural extension.

Households disagreed with the statement that there has been no change in climatic conditions in recent years. This implies that rural households are experiencing an alteration in weather conditions, evidenced by a dwindling of environmental resources such as water and fuel wood as stated by key informants. They disagreed that climate change does not affect the amount and quality of water, wood, and other natural resources. This is because with climate change, household members responsible for such roles, especially women and children, spend more time in search of water and fuel wood. Usually, they have to search deeper into forests (FAO 2008).

Respondents disagreed that climate information is not a priority for planning in livelihoods. This is because with relevant climate information, such as weather forecast, risks can be minimized. They disagreed that climate change has no effect on the health status of rural households. Also, they disagreed with the statement that climate change has not decreased the quantity and quality of food consumed by households. This implies that climate change has affected the food security of rural households. According to CARE (2011), climate change has made rural households resort to drastic and unsustainable measures such as food rationing and borrowing. Such conditions lead to hunger, undernourishment, and poor health status which can prevent them from achieving profitable livelihoods.

However, the respondents were undecided about statement 2 which stated that men and women were equally vulnerable to climate change (mean = 2.82). This is unlike statement 14 to which respondents agreed that insecure access to production resources contributed to women’s vulnerability (mean = 3.66). This may stem from their culture which still makes it difficult for them to perceive gender gaps (Antwi-Agyei et al. 2014) due to conditions such as insecure access to production resources, poor level of education, etc. These stand as barriers to women empowerment and women contributing successfully to the welfare of their households in the face of climate change. Interviews revealed that women involved in agricultural production do not get a fair bargain either as hired labor or in the sales of their produce. According to CARE (2011), this can prevent them from fulfilling their responsibilities such as providing food for their families. Also, it can serve as a barrier to learning useful skills that can aid sustainable adaptation to climate change.

A grand mean of 3.92 implies that generally respondents have a positive perception of climate change. This means they recognize its limiting tendencies (Grimberg et al. 2018). It limits the potentials of their livelihoods in generating sufficient income and the achievement of food security. It serves as an impediment to the achievement of a vibrant rural sector which can contribute meaningfully to poverty eradication and national development. Interviews with key informants revealed extensive and effective contact with agricultural extension. Therefore, agricultural extension services can leverage on their positive perception to provide enlightenment for the protection of the ecosystem. This will discourage bush burning and loss of biodiversity through intensive hunting of unique plant and animal species. Agroforestry can also be encouraged as a viable option to building resilient livelihoods.

Relationship Between Perception and Coping Strategies of Respondents

A chi-square test of independence between respondents’ perception of climate change and their choice of coping and adaptation strategies was carried out to determine if there is relationship between the two variables. The determinants of adaptive capacity among rural households are better assessed at household level to provide pragmatic and empirical evidence since adaptive capacity can vary dramatically between individuals, households, and communities (Osumanu et al. 2017). Table 4 shows the chi-square result of the relationship between perception and the coping and adaptation strategies of the households.

Table 4 shows that there was a significant relationship between respondents’ perception of climate change and mixed cropping (χ2 = 55.433, p = 0.042). This implies that respondents’ perception of climate change influences the choice of mixed cropping as an adaptation strategy. Thus, their perception encourages the use of mixed cropping as an adaptation option which may be the reason for about 45.2% of the households choosing this strategy. Moreover, mixed cropping comes at little or no cost to the households and minimizes risk of total crop failure.

There was a significant relationship between respondents’ perception and planting of improved varieties (χ2 = 55.866, p = 0.031). This implies that their perception encouraged the choice of planting improved varieties which are less sensitive to climate change in order to improve their yield. This may be as a result of the impact of agricultural extension in the study area to give advice in order to build the resilience of livelihoods, especially agricultural production.

There was also a significant relationship between respondents’ perception of climate change and change in harvest dates (χ2 = 56.753, p = 0.026). Respondents’ perception is, therefore, associated with the choice of harvest date which may be as a result of access to climate information or based on personal experiences. Planting new crop varieties, according to Alam et al. (2017), is an important strategy in climate change adaption among rural households. The authors also stated that perception and local knowledge contribute to the decision of choice of harvest date of crops to prevent yield loss occasioned by climate hazards.

The result shows that rural households would utilize innovative, available, and affordable sustainable adaptation strategies based on information that educates them on their benefits, thereby modifying or changing their perception. This is corroborated by Osumanu et al. (2017) that the determinants of local adaptive capacity, like household-level adaptive capacity, include their asset base, institutions and entitlements available in the community, the knowledge and information available to them, innovation, and flexible decision-making. These allow for the adoption of sustainable adaptation strategies that help build more resilient livelihoods.

Conclusion

Rural households employ diverse coping and adaptation strategies in response to climate change impacts on their livelihoods. Although their perception of climate change was favorable and indicated their understanding of its negative effects on their livelihoods, it did not take cognizance of women’s insecure access to production resources. While some of the adaptation strategies, such as borrowing and sale of assets, are unsustainable, others, such as adjusting harvest and sowing dates, can be better facilitated by utilizing media to obtain weather forecasts in making planning decisions.

Government can partner with the communities and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the development of early warning systems and easily accessible weather forecast in simple language. Effort should also be made in the establishment of irrigation technology in rural communities in order to reduce the drudgery of fetching water. This will boost food security and income generation among rural households. Government policies that will build the capacity of agricultural extension in providing information on crop choices and agroforestry activities should be implemented.

Women’s access to production resources can be improved through policies that encourage greater gender inclusion in credit facilitation targeted at rural livelihoods. NGOs can target the erosion of institutional barriers to women empowerment by educating rural households on its implications for the rural economy and national development. Such training should also incorporate biodiversity protection. This is crucial to ending and reversing the effects of the dangers of harmful and ineffective practices on the environment. Agricultural extension can enlist the help of opinion leaders in the communities to drive the change in belief systems so as to promote the implementation of sustainable adaptation strategies.

References

Abdulai A, Ziemah M, Akaabre P (2017) Climate change and rural livelihoods in the Lawra District of Ghana. A qualitative based study. Eur Sci J 13(11):160–182

Agyei F (2016) Sustainability of climate change adaptation strategies: experiences from Eastern Ghana. Environ Manag Sustain Dev 5(2):84–103

Akinbami C, Ifeaanyi-Obi C, Appiah D, Kabo-Bah A (2016) Towards sustainable adaptation to climate change: the role of indigenous knowledge in Nigeria and Ghana. Afr J Sustain Dev 6(2). Available http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajsd/article

Alam G, Alam K, Mushtaq S (2017) Climate change perceptions and local adaptation strategies of hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Clim Risk Manag 17:52–63. Available http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221209631730013X/

Antwi-Agyei P, Dougill A, Stringer L (2014) Barriers to climate change adaptation: evidence from Northeast Ghana in the context of a systematic literature review. Clim Dev 7(4):297–309

Apurba K, Haque C (2017) Multi-dimensional coping and adaptation strategies of small-scale fishing communities of Bangladesh to climate change-induced stressors. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manag 9(4):446–448

Asrat P, Simane B (2018) Farmers’ perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in Dabus Watershed, North-west Ethiopia. Ecol Process 7(7). Available https://ecologicalprocesses.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/

Bhatasara S, Nyamwanza A (2017) Sustainability: a missing dimension in climate change discourse in Africa? J Integr Environ Sci 15(1):83–97

Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (2011) Understanding vulnerability to climate change: insights from application of CARE’s climate vulnerability and capacity and analysis (CVCH) methodology. Available http://www.careclimatechange.org/files/adaptation

Faleyimu O, Akinyemi O, Agbeja B (2010) Incentives for forestry development in the South-west Nigeria. Afr J Gen Agric 6(2):67–76

Food and Agriculture Organization (2003) Enhancing support for sustainable livelihoods. Committee on agriculture. 17th session. Item 7 on provisional agenda. Available http://www.fao.org/

Food and Agriculture Organization (2008) Climate change and food security: a framework document. Available http://www.fao.org/forestry/15538

Galotti K (1994) Cognitive psychology in and out of the laboratory. Available http://www.sagepub.com/sites

Gebre GG, Isoda H, Rahut DB, Amekawa Y, Nomura H (2019) Gender differences in agricultural productivity: evidence from maize farm households in Southern Ethiopia. Geojournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1070801910098y

Grimberg B, Ahmed S, Colter E, Zachariah M, Mellaned F (2018) Climate change perceptions and observations of agricultural stakeholders in the Northern Great Plains. Sustainability 10. Available http://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the 4th assessment report of the IPCC. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jones L, Ludi E, Jeans H, Barihaihi M (2017) Revisiting the local adaptive capacity framework: learning from a research and programming framework in Africa. Clim Dev 7(4):1–11

Loison S (2015) Rural livelihood diversification in Sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review 51(9). Available http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjds20

Maddison (2007) The Perception of and Adaptation to Climate Change in Africa. Policy Research Working Paper 4308. WPS4308. The World Bank , Development Research Group, Sustainable Rural and Urban Development Team pp 3–15

Mcdonald S (2012) Perception: a concept analysis. Available http://www.researchgate.net/publication/

Moser S, Ekstrom J (2010) A framework to diagnose climate change adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(51):22026–22031

National Population Commission (2006) Population and housing census. Data for national planning. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25434601/ Vol. 33 No.1 pp206210

Ndamani F, Watanabe T (2015) Farmers’ perceptions about adaptation practices to climate change and barriers to adaptation: a micro-level study in Ghana. Water 7:4593–4604

Olajide O, Akinlabi B, Tijani A (2012) Agriculture resource and economic growth in Nigeria. Eur Sci J 8(22):103–116

Omonona BT (2009) Quantitative analysis of rural poverty in Nigeria. International Food Policy Research Institution. nssppb17.pdf

Osumanu I, Anaiah P, Yelfaanibe A (2017) Determinants of adaptive capacity to climate change among smallholder rural households in the Bongo District, Ghana. Ghana J Dev Stud 14(2):141–163

Oyinloye R, Oloukoi J (2013) An assessment of the Pull between Landuse and Landcover in Southwestern Nigeria and the Ensuing Environmental Impact. International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) Working Week 2013. Environment for sustainability. Held at Abuja, 2013

Yaro J (2006) Is reagrarianisation real? A study of livelihood activities in rural northern Ghana. J Mod Afr Stud 44(1):125–156

Zoundji G, Witteveen L, Vodouhe S, Lie R (2017) When baobab flowers and rainmakers define the season: farmers’ perceptions and adaptation strategies. Int J Plant Animal Environ Sci 7(2). Available http://www.ijpaes.com/admin/php/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry

Fasina, O.O., Okogbue, E.C., Ishola, O.O., Adeeko, A. (2020). Sustainable Climate Change Adaptation in Developing Countries: Role of Perception Among Rural Households. In: Leal Filho, W., Oguge, N., Ayal, D., Adeleke, L., da Silva, I. (eds) African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_87-1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_87-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-42091-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-42091-8

eBook Packages: Springer Reference Earth and Environm. ScienceReference Module Physical and Materials ScienceReference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences