Abstract

Cassava and sweetpotato are major factors in food security across sub-Saharan Africa. Though cassava and sweetpotato varieties that are early maturing and resistant to diseases have been developed, many farmers still grow local varieties. Cassava and sweetpotato cultivars that mature between 6 and 12 and 3 and 4 months after planting, respectively, are available. The objective of the synthesis was to obtain a general overview of cassava and sweetpotato production in Matiliku subcounty of Makueni County in semi-arid eastern Kenya before the establishment of a seed system for them. Participatory rural appraisal and focused group discussions with key stakeholders in Makueni County on the current status of these crops provided very useful information. It was observed that there are a few early cassava and sweetpotato adopters, meaning a lot of effort in communicating the need to commercialize them needs to be made. Even though the farmers had sufficient experience in growing them at subsistence level, they were searching for cultivars that combine both nutritional and food security. There is a need to engage more extension service providers in order to campaign on their adoption. There is a need to carryout training and awareness creation on their role in food security and wealth creation.

This chapter was previously published non-open access with exclusive rights reserved by the Publisher. It has been changed retrospectively to open access under a CC BY 4.0 license and the copyright holder is “The Author(s)”. For further details, please see the license information at the end of the chapter.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Cassava and sweetpotato produce starchy tuberous roots. Cassava and sweetpotato may be sweet or bitter depending on the variety. The crops are resistant to drought and are mainly propagated through stem cuttings or vines. Cassava and sweetpotato can adapt to diverse climatic conditions, survive long dry spells, and can be harvested and stored on a flexible time schedule, all of which qualifies cassava and sweetpotato as food security crops and technologies that respond well to climate change. Cassava and sweetpotato tuberous roots are rich in carbohydrates and are a staple food for many Africans. They are also used to manufacture alcohol. The leaves are richer in protein and minerals than the tuberous roots both qualitatively and quantitatively and are used both as vegetable and fodder. Cassava and sweetpotato have high potential if people are sensitized to their usefulness and nutritive value. Currently, women and children usually grow cassava and sweetpotato as food security crops. However, the scenario changes when the two crops are grown for commercial purposes with men playing a prominent role (Nweke et al. 2002).

Thirty-centimeter (30) stem cassava cuttings are planted upright, slanting, or buried horizontally. Sweetpotato is propagated also from 30 cm vines, about 2/3 s of which are inserted in the ground. Both crops have a great yield potential of 20–50 t/ha of root dry weight in the tropics. This yield potential has yet to be exploited as farmers are producing an average of less than 10 t/ha. Cassava and sweetpotato provide 8% or more of the minimum calories requirements of some 750 million people in the tropics, making it one of the most important energy sources in the human diet. Cassava and sweetpotato have great potential as industrial starch production crops and hence provide employment at the production, marketing, and sales levels. Given that the demand for food and feed remains unsatisfied and the time pressure to meet the challenge is increasing rapidly, cassava and sweetpotato can help alleviate this problem.

Cassava and sweetpotato produce about 10 times more carbohydrates than most cereals per unit area and are ideal for production in marginal and drought prone areas, which comprise about 75% of Kenya (Githunguri et al. 1998; Githunguri 2002; Nweke et al. 2002). Despite their great potential as a food security and income generation crops among rural poor in marginal lands, their utilization remain low. The potential to increase cassava and sweetpotato utilization is enormous with increased recipe range (Githunguri 1995). The International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) has officially recognized cassava as a new cash commodity and a vital food in Africa. The Common Fund for Commodities has recognized cassava as an internationally tradable commodity. The Intergovernmental Group on Grains has adopted cassava as a commodity. Cassava and sweetpotato can accelerate development and improve livelihoods of Kenyan rural communities as has been demonstrated in Vietnam and Thailand. Adoption of improved cassava production, processing, and marketing technologies earns these countries about one million US$ per annum. This model is being pursued by initiatives in Africa such as the NEPAD Pan African Cassava Initiative, Sub-Saharan Africa Challenge Program, and the South African Root Crops Research Network and East African Root Crops Research Network.

Cassava and sweetpotato are major factors in food security across sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, cassava is grown in over 90,000 ha with an annual production of about 540,000 tons. Cassava (Mahihot esculenta Crantz.) is a relatively neglected tropical root crop in East and southern Africa (Githunguri 1995; Githunguri et al. 2017a, b, c). It is grown widely in East Africa in areas below 1500 m above sea level (Acland 1985). Cassava production in Kenya is concentrated in three main regions: Coastal, Central, and Western region. Western and Coastal regions are the main cassava producing areas, producing over 80% of the recorded cassava output in the country (Githunguri et al. 2017a). Though cassava is considered to be a food security crop in the sub-Saharan Africa, its production in Kenya is low compared to other crops like maize, beans, and sorghum. Its consumption is low especially in the central region of Kenya where it is considered a poor man’s crop and is usually consumed during periods of food scarcity. Despite its high production in the coastal and western regions of Kenya, utilization is limited to human consumption. In order to promote production, which has been decreasing in recent years, there is a need to explore and identify other uses of cassava.

According to FAO (1990), Africa produces about 42% of the total tropical world production of cassava and contributes significantly to food security across sub-Saharan Africa. Githunguri et al. (1998) and Nweke et al. (2002) noted that cassava could grow well in marginal lands, requires low inputs, and is tolerant to pests and drought. Cassava is grown in over 90,000 ha with an annual production of about 540,000 t in Kenya and could remain in the ground for 7–24 months after planting and then harvested thereafter (Githunguri et al. 2017a). Utilization of cassava remains low in Kenya because the fresh root tubers are limited to roasting and boiling for consumption only despite its great potential as a food security and income generating crop (Githunguri 1995; Githunguri et al. 2017a). However, it should be noted that cassava is widely used in Kenya by almost all communities despite the fact that there is still a lot of room for expansion on its use especially by industrialists who have yet to fully utilize cassava in food and stock feed manufacture. The Home Economics Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and other organizations have a wide range of options in developing cassava recipes acceptable to a larger community (Githunguri 1995; Githunguri et al. 2017a). In Kenya, cassava is the second most important food root crop after Solanum potato. However, due to its small production base, it is ranked 36th out of 50 in KALROs 1991 priority setting exercise (KALRO 1995; Githunguri 1995; Githunguri et al. 2017a). There is a slow but steady increase in cassava production because its consumption has a direct effect on demand.

Variability studies by Rai et al. (1986) on cassava showed that phenotypic variance was higher than genotypic variance for all characteristics, which included plant height, tuberous root girth, length, and weight. Later rain-fed trials involving several cassava cultivars showed significant genotype by environment (g × e) interaction for yield (Naskar et al. 1989). Selection for a slightly higher than optimal leaf area index, and hence greater biomass, can lead to stable cassava yields across both favorable and stress environments. Further, according to Nartey (1981) and Githunguri et al. (2014), the harvested cassava yields depend on the distribution of dry matter between the useful and other parts of the plant, which may be affected by the sink capacity of the useful parts to accept photosynthates, as well as the capacity of the leaves to supply it. In sub-Saharan Africa, most boil and eat fresh cassava consumers prefer roots with high dry matter contents, which are boiled and consumed as vegetable (Nartey 1981; Githunguri et al. 2014). It is important to note that Dixon et al. (1994) had reported negative correlation between root dry matter content and root cyanogenic potential which is important when selecting cassava varieties targeting fresh tuberous root consumers. According to IITA (1990b) and Githunguri et al. (2016), useful yields of the cassava crop depend on its total biomass and its distribution among useful parts. As such, since the total light intercepted strongly depends on leaf area, the best yielding cassava is one that establishes adequate and efficient photosynthetic surface sufficiently early in the cropping season, maintains it at least over the duration of the moisture cycle, and partitions dry matter into yield (Cock 1985); IITA 1990a). Other studies (IITA 1990b) have shown that best root yields are obtained at a leaf area index of 3.5, with general reduction in yield as the leaf area indices increase.

African farmers usually grow cassava under field conditions where one or more of the resources are limiting. However, it should be noted that most of the research works carried out are under optimum management conditions (Githunguri et al. 2006). Importance of cassava as an industrial crop is increasing rapidly in several countries within the tropics and especially sub-Saharan Africa (Ayinde et al. 2004; Azogu et al. 2004; EFDI-Technoserve 2005; Ezedinma et al. 2005; Githunguri 1995; Onyango et al. 2006). According to several studies (Githunguri 2002; Odongo 2008; Tivana and Bvochora 2005), safety of cassava products is important and could be affected by agro-ecological zones and genotypes. According to Ekanayake et al. (1997a) and Ekanayake et al. (1997b), a cassava plant possesses several physiological parameters and processes that confer to it the ability to produce modest yield under a range of both abiotic and biotic stresses. Some of these parameters include heliotropism, leaf drooping, long fibrous roots, loss of leaves, high water use efficiency, and large source potential, and sink capacity (Ekanayake 1998; Githunguri 2002). Other studies have shown that the cassava value chain has three main components: field production, processing, and marketing (Githunguri et al. 2017a, b, c). Though cassava varieties that are early maturing and resistant to diseases have been developed, many farmers in the cassava growing regions (coastal, central, and western) still grow local varieties (Githunguri et al. 1998, 2006, 2007a; Githunguri 2002). In addition, early maturing, high yielding, disease, and pest tolerant cassava cultivars developed through participatory breeding by the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) are available to farmers (Githunguri et al. 2006, 2007a).

Sweetpotato is an important staple food in the East African region after banana and maize. It has high potential for livestock feed and industrial use as well (Onwueme 1978). Generally, small-scale farmers using traditional farming systems on marginal soils produce most of the sweetpotatoes and cassava. According to Onwueme (1978), yields of sweetpotato and cassava vary with cultivar, disease resistance, and location and production practices. Constraints to sweetpotato production in Kenya include the sweetpotato weevil, lack of adequate disease and pest-free planting materials, poor cultural practices, lack of appropriate storage and processing technologies, and poor market infrastructure (Lusweti et al. 1997; Githunguri et al. 2003). Although some trade occurs, there is minimal official record of international trade in sweetpotato. Kenya mainly meets her consumption needs almost exclusively through internal production. Thus, sweetpotatoes like cassava are consumed locally and hence traded in a closed economy. This suggests that prices are mainly dependent on local forces of supply and demand. Due to lack of external market, the aggregate demand for sweetpotato within Kenya is assumed to equal supply (Odendo et al. 2001). One of the major constraints towards cassava and sweetpotato production and commercialization is their low and slow multiplication ratio due to their being vegetatively propagated. This constraint is further compounded when their production is carried out in the arid and semi-arid areas where their multiplication can only be effectively and commercially multiplied under irrigation and high inputs. Most local cassava and sweetpotato cultivars are low yielding and are late maturing. Though cassava and sweetpotato varieties that are early maturing and resistant to diseases have been developed, many farmers still grow local varieties. KALRO has sweetpotato cultivars that mature between 3 and 4 months and cassava cultivars that produce appreciable yields between 6 and 12 months after planting. As such, the specific objective of this synopsis was to obtain a general overview of cassava and sweetpotato production in Matiliku Division Makueni District in semi-arid eastern Kenya before the establishment of a seed system for the two crops.

Farmer Interviews

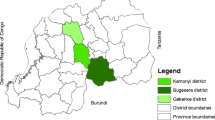

Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) and Focused Group Discussions with farmers, local leaders, extension staff, and other stakeholders were conducted at Matiliku Division in Makueni District. The PRA involving 51 farmers was conducted at a farm with an elevation of 1043 m above sea level located on Latitude S: 011.867812 and Longitude E: 042.78234. Using a semi-structured questionnaire, farmers were interviewed individually whereby an overview on cassava and sweetpotato production in Matiliku was obtained. The data was subjected to descriptive analysis methods while charts were generated using Microsoft Excel application. The results were used to inform decisions on their training and cassava and sweetpotato production requirements.

Survey Observations and Synthesis in a Semi-Arid Area in Kenya

Figure 1 shows about 35.3% of the farmers put 0.25 acres under cassava cultivation while 13.7% have a few stands and 33.3% do not grow cassava at all. About 11.8% of the respondents put in cassava on land ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 acres and this category could be the early adopters.

The number of years under cassava production ranged between 1 and 40 years with only a few (7.7%) farmers indicating to have been growing cassava for a period above 40 years (Fig. 2). The majority of farmers, about 41.1%, have grown cassava for only 1 year while the rest had cassava-growing experience ranging between 2 and 30 years in proportions ranging between 5.1 and 10.3%. These results suggest that cassava is grown as a subsistence crop and a lot needs to be done if it is going to be commercialized in Matiliku.

According to Table 1 the majority of farmers, about 40.5%, were growing a local cassava cultivar whose name seemed to be unknown while 31.0% were growing a cultivar whose origin was uncertain. Among the known local cultivars, Kitwa was being grown by 7.1% of the respondents. A similar percentage (7.1%) of respondents were growing the improved “Mucericeri” cultivar obtained from KALRO and FIPs Africa. Other minor cultivars included 990,005, “Kiisungu,” and “Nyawo.” These results suggest that even though KALRO and some significant service providers have started distributing improved cultivars, a lot still needs to be done if cassava is going to play its rightful role in supplying the much needed calories.

Table 2 shows that the most significant methods of utilization include boiling and eating cassava for breakfast and chewing raw as a snack. About 10.1% of respondents mix cassava with maize and beans (“githeri”) while 17.7% grow cassava for sale in the local market. Only 5.1% of the respondents indicated they have not utilized cassava in any way. The results indicate that there is very little processing of cassava taking place in Matiliku suggesting that there is need to carryout training and awareness creation on the role of cassava in food security and wealth creation.

Results in Table 3 show that KALRO (35.9%) has been largely responsible in the introduction of cassava as a viable technology in this area. 25.6% of the respondents were not certain about the origin of their cultivars, whereas 20.5% obtained them from the local market. It seems 20.5% of the respondents purchased cassava cuttings from the market, which is a positive sign on the viability of cassava being taken up as a commercial venture. There is need to increase the number of extension service providers in the area.

Figure 3 shows that the majority of respondents comprising 52.5%, 30%, and 10% grow sweetpotatoes on 0.25, 0.125 acres of land and only a few stands, respectively. The rest 7.5% grow sweetpotatoes on pieces of land ranging from 0.5 to 2 acres who seem to comprise the group of early adopters. These results suggest that sweetpotato is also grown as a subsistence crop. Serious efforts need to be put in place in order to move sweetpotato from subsistence level to commercialization in Matiliku.

Figure 4 shows that majority of the respondents, about 60%, have mainly grown sweetpotatoes for the last 3 years. The rest 40% have mainly grown sweetpotato for a period ranging from 4 to 30 years. This suggests that the concerted efforts that have been put in place by KALRO and its partners in extension service providers during the last 4 years have paid divided and all that is needed is to sustain the efforts.

The results in Table 4 show that 21.2% of the respondents were growing a local cultivar of an unknown origin while 16.7% of the farmers were growing an unknown improved cultivar presumably obtained from KALRO or other extension service providers. Sallyboro, an improved orange-fleshed sweetpotato cultivar, and “Mwezi moja,” a drought tolerant local cultivar, were the only cultivars being grown by an appreciable number of respondents, 15.2% and 10.6%, respectively. The rest of the 13 cultivars were thinly spread among the respondents with proportions ranging between 1.5% and 7.6%. The multiplicity of cultivars suggests that the farmers have accepted sweetpotato as an important part of their food security technologies and it seems they have been searching for a suitable cultivar. It seems a combination of Sallyboro and “Mwezi moja” have the qualities the farmers have been looking for: namely, food and nutrition security. There is a lot of potential to commercialize sweetpotato production in Matiliku if a sustainable seed system is established.

According to Table 5, the most popular method of utilization of sweetpotato is boiling and taken for breakfast. The sweetpotato is also a tradable commodity with 26.5% of respondents selling them in the local market. About 6% of the late adopters had not utilized sweetpotato at all. A few farmers were feeding sweetpotato vines to livestock while there was very little processing. In the area of utilization, there is a lot of room for training and improvement. However, farmers here like in the major sweetpotato producing areas in Western and Central Kenya could target the huge fresh market in Nairobi and other major urban centers.

Table 6 shows the origin of sweetpotatoes is mainly from KALRO (35.8%), neighboring farmers (34.0), and FIPs Africa (20.8). It seems KALRO and FIPs Africa have made major inroads in addition to the farmers being receptive and a willing congregation.

Results in Table 7 show that the majority, over 70%, of cassava and sweetpotato farmers had attained at least the Primary Level of education with more than half of them having a secondary level of education. At least 2% of the farmers had an email address. The results suggest that the majority of the farmers were educated and had already started embracing modern technology meaning it will be easy to convince them to adopt the new cultivars.

Cassava: Postanalysis

Cassava production and its optimized food, nutritional, and industrial positioning as a climate smart crop faces challenges including diseases, late maturing varieties, pests and lack of climate smart adaptable varieties, low yields, weak seed systems, insufficient value addition, limited market linkages, and insufficient mapping of gendered roles in production and marketing. Limited availability of clean planting materials has resulted in few agro producers growing improved varieties, hence reduced root yield and quality. The majority of cassava famers (93%) in Kenya use planting materials from their own or neighbor’s fields (Githunguri et al. 2014), hence a continued build-up of diseases and pests (Githunguri and Njaimwe 2013a, b, c, d; Githunguri 1983a, b). Unfortunately, the perception of cassava as a poor peoples’ food has impacted negatively on national efforts to promote cassava as a viable, commercially marketable product which has confined it to subsistence production, rudimentary processing, and limited consumption (Githunguri et al. 2017a). There is need to address and change this negative attitude towards cassava through advocacy and change in policy. The minimal processing techniques are usually tedious, time-consuming, low yielding resulting in products with unpredictable qualities and hence rarely stocked in markets. We believe that adjustments of locally available processing technologies accompanied by an aggressive vigorous promotion and marketing campaign will significantly raise the profile of climate smart crops like cassava and thus contribute to the improvement of food security, incomes, and community resilience.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is the fifth most important food crop in the world (Githunguri 2002). It produces more energy per unit area compared to most cereals (Githunguri et al. 2015; Githunguri and Amata 2015). The crop is drought tolerant and produces under marginally fertile soils where other crops fail (Githunguri et al. 2014); hence, it is the most resilient to climate change among all major African crops (Jarvis et al. 2012). Cassava is grown by smallholder agro producers in western, coastal, and eastern Kenya. Considering that about 75% of Kenya is arid or semi-arid and the majority of small-scale farmers in cassava growing areas are women, increased cassava production and consumption will contribute greatly towards poverty alleviation, food security, women empowerment, and wealth creation of the nation (Githunguri et al. 2007). In 2017 the country produced 1,112,000 tonnes from 90,394 ha, translating to 12 t/ha which is lower compared to 16 to 24 t/ha in China, Indonesia, and Thailand (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO 2017) and the crop potential of 90 t/ha (Cock et al. 1979). Lamu and Kisumu are among the major cassava producing counties in Kenya and the crop contributes 6% of the total household incomes (MOALF 2018). Production is dominated by low-yielding varieties that are susceptible to pests and diseases under poor crop and pest management practices. Major diseases are cassava mosaic (CMD) and cassava brown streak (CBSD) disease which cause yield losses of up to 100% with CBSD causing necrosis which renders roots unfit for food, feed, and industrial purposes (Monger et al. 2010). Pests such as cassava mealybugs (CMB) and cassava green mites (CGM) affect production particularly during the dry periods. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) has identified improved varieties such as MM95/0183, Midgyera, and Katune (990005) and that are high yielding, early maturing, and tolerant to pests and diseases. Therefore, validating and upscaling improved varieties and good agronomic, pest and disease management technologies will contribute to increased productivity. Wide adoption of improved varieties will be enhanced if planting materials are bulked in close proximity to production areas to reduce transportation costs. Lack of an efficient seed delivery system has resulted in limited availability and accessibility of clean planting materials, resulting in 93% of the agro producers in Kenya using infected planting materials (Amata et al. 2012; Ekanayake and Githunguri 2000). This causes a buildup of pests and diseases further contributing to low productivity of clonally propagated crops (Githunguri et al. 1992). There is a need to have a system compliant with national regulations to avail high quality planting materials to agro producers, to address losses attributed to these pests and diseases. Use of tissue culture and three node technology to mass propagate disease free planting materials and bulk at three levels – primary (NARS, breeders’ seed), secondary (Government, NGOs and other private Institutions), and tertiary (village seed entrepreneurs) – could be beneficial in availing clean materials to agro producers. Cassava utilization in the target counties is limited to boiling, deep frying, roasting, and blending cassava with maize, millet, or sorghum flour to make porridge or “ugali” (Githunguri 1995). In Nigeria, the crop is processed into feeds and food products like garri. Cassava can replace 10–30% of maize in food and feeds, 60–70% in confectionery products, and up to 60% of barley in beer making, hence can relieve the demand for and importation of wheat and save on foreign exchange. This potential has been recognized and the Ministry of Agriculture in Kenya is enacting a law to enforce blending of maize and wheat with cassava flour. Production of high quality flour is a requirement for blending and hence improved processing technologies that will ensure safety of products will be validated and up-scaled. In addition, new products will be introduced to entrepreneurs who will be linked to markets to create employment and increase income generation.

Sweetpotato: Postanalysis

Sweetpotatoes are important in the economy of poor households and are a major source of subsistence and cash income to farmers in agroclimatically disadvantaged regions and even in high potential areas of Kenya. Constraints to sweetpotato production in Kenya include the sweetpotato weevil, sweetpotato virus complex, lack of adequate disease and pest free planting materials, poor cultural practices, lack of appropriate storage and processing technologies, and poor market infrastructure. Effective control of major biotic and abiotic stresses on sweetpotatoes through selection and breeding of clones’ resistance and/or tolerant to them plus the availability of clean planting material will boost food availability significantly in arid and semi-arid lands through the establishment of sweetpotato based industries in sweetpotato growing areas. The objectives of the Root and Tuber Crops Programme in the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) are to develop sweetpotato varieties that are widely adapted to diverse agro-ecological zones. The varieties should also be high yielding, early bulking, and drought resistant/tolerant, resistant to major biotic and abiotic stresses and have good root quality and especially high in ß-carotene content (orange fleshed sweetpotatoes). The Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization has recognized the importance of involving farmers in their selection and breeding research programs.

Sweetpotato produces starchy tuberous roots. The crop is resistant to drought and is mainly propagated through vines. Sweetpotato can adapt to diverse climatic conditions, survive long dry spells and can be harvested and stored on a flexible time schedule, all of which qualifies it as a food security crop. Sweetpotato tuberous roots are rich in carbohydrates and are a staple food for many Africans. They are also used to manufacture alcohol. The leaves are richer in protein and minerals than the tuberous roots both qualitatively and quantitatively and are used both as vegetable and fodder. Sweetpotato has high potential if people are sensitized to their usefulness and nutritive value.

Sweetpotato is propagated also from 30 cm vines about 2/3 s of which are inserted in the ground. Both crops have a great yield potential of 20–50 t/ha of root dry weight in the tropics. This yield potential has yet to be exploited as farmers are producing an average of less than 10 t/ha (Nweke et al. 1994). Sweetpotato provides 8% or more of the minimum calories requirements of some 750 million people in the tropics, making it one of the most important energy sources in the human diet. Sweetpotato has great potential as an industrial starch production crop and hence provide employment at the production, marketing, and sales levels. Given that the demand for food and feed remains unsatisfied and the time pressure to meet the challenge is increasing rapidly, sweetpotato can help alleviate this problem.

Sweetpotatoes have the potential to contribute towards increased and sustainable food security, poverty alleviation, and wealth and employment creation. As such, the Kenyan government needs to have challenges and opportunities addressed along the sweetpotato value chain. Kenya’s Economic Recovery Strategy of 2003 focuses on creating employment and wealth in the various subsectors including agriculture which contributes about 30% to the gross domestic product and provides about 70% of employment opportunities annually (MoA 2005). The vision of the government Strategy for Revitalizing Agriculture and Kenya Vision 2030 (National Economic and Social Council of Kenya (NESC) 2007) is to make the sector profitable, commercially oriented, and competitive (MoA 2005). Value addition and efficiency in production, processing, and marketing of high quality competitive sweetpotato products in Kenya and beyond will be used to enhance household incomes, employment, and food and nutrition security.

Despite its great potential as a food security and income generation crop among rural poor in marginal lands, its utilization remains low. However, its utilization can be increased with an enhanced number of recipes. Sweetpotato can accelerate development and improve livelihoods of Kenyan rural communities as has been demonstrated in China. Studies indicate sweetpotato seed, flour, crisps, starch, livestock feeds, and ethanol as the six best bet sweetpotato technologies. However, there is need to focus on sweetpotato seed. Several small-scale sweetpotato-based technologies have been initiated in a number of countries and similar models can work for Kenya (Onyango et al. 2006). What is lacking is an effective technology transfer mechanism that makes it possible for sweetpotato farmers and processors in Kenya to test, select, and adopt or adapt the best options. There is need to train farmers and processors on good sweetpotato field production and manufacturing practices and facilitate their access to microcredit and market avenues to catalyze sufficient investment in the sweetpotato industry.

A successful commercial sweetpotato seed industry could lead to increased sweetpotato field production which could in turn lead to processing of products and better markets for sweetpotato products leading to increased incomes to the rural community thus leading to a reduction in poverty levels among them. This could also lead to increased utilization of quality sweetpotato products and enhanced food security as proposed by the ERS and the SRA. Quality sweetpotato products have the potential of greatly contributing to improved health of the rural populations and enhance nutritional security among small scale farmers.

With successful interventions, there will be need for policy makers to create policy instruments to absorb surplus sweetpotato, which will create incentives for local producers. Making it mandatory for processors to use a certain percentage of sweetpotato, flour in making livestock feeds could achieve this. This would promote use of sweetpotato in addressing rural food security, industrialization, employment creation, rural urban migration, and rural youth occupation.

The sweetpotato value chain has three main components: field production, processing, and marketing. We will build strong ties with both public and private institutions engaged in research, extension, and social development in order to accomplish this linkage by the end of project. Though sweetpotato varieties that are early maturing and resistant to diseases have been developed, many farmers in the sweetpotato growing regions still grow local varieties. Many local sweetpotato cultivars take more than 6 months to mature, whereas the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization has sweetpotato cultivars that mature between 3 and 4 months. Intensive multiplication and dissemination of the newly bred early maturing high yielding disease and pest tolerant cultivars will result in increased sweetpotato production and ensure a source of food and income for the rural households. Early maturing, high yielding disease, and pest tolerant sweetpotato cultivars developed through participatory breeding at various Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization Centres are available.

Conclusions

There are a few early cassava and sweetpotato adopters, meaning cassava and sweetpotato are still being grown as a subsistence crop and a lot needs to be done if they are going to be commercialized in Matiliku. The farmers had sufficient experience in growing the two crops albeit at subsistence level. The farmers seemed to be searching for cultivars that combined both nutritional and food security. There is need to engage more extension service providers than there are currently in order to hasten the adoption of new cultivars. There is very little processing of these crops taking place in Matiliku suggesting that there is need to carryout training and awareness creation on their role in food security and wealth creation. Sallyboro, an improved orange-fleshed sweetpotato cultivar, and “Mwezi moja,” a drought tolerant local cultivar have been accepted by the farmers. There is a lot of potential to commercialize cassava and sweetpotato production in Matiliku if a sustainable seed system is established. Cassava and sweetpotato are tradable commodities in Matiliku. Farmers could target the huge fresh market in Nairobi and other major urban centers. Majority of the farmers are educated and could easily adopt new technologies.

References

Acland JD (1985) East African crops: an introduction to the production of field and plantation crops in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda [by] J. D. Acland. Longman [for the] Food and Agriculture Organization, London, 1971. ISBN: 0582603013. 252 p

Amata R, Ateka E, Kasina M, Githunguri C, Wangai A, Miano D, Mamati E, Githiri M, Kamau J, Ndolo P, Obiero H, Muli B, Mwaniki S, Kwach J, Lelgut D, Gichangi A, Macharia I, Kagondu A, Kuyia J, Sila M, Gathara V, Kihurani A, Agili S, Momanyi V, Mbugua B, Odero B, Wekesa N, Ochieng V, Omari J, Mbugua F, Kitisya A (2012) Constraints and opportunities of a clean seed delivery system for cassava and sweetpotato in Kenya. “Agricultural innovation system for improved productivity and competitiveness in pursuit of vision 2030”. In the Proceedings of the 13th KARI Biennial Scientific Conference held in Nairobi at Kenya Agricultural Research Institute Headquarters from 22nd to 26th October 2012. pp 612–622

Ayinde A, Dipeolu O, Adebayo K, Oyewole OB, Sanni LO, Adusei J, Westby A (2004) A cost-benefit analysis of the processing of a shelf stable cassava fufu in Nigeria. In: Book of abstracts of the sixth international scientific meeting of the cassava biotechnology network. CIAT, Cali

Azogu I, Tewe O, Ezedinma C, Olomo V (2004) Cassava utilisation in domestic feed market. Root and Tuber Expansion Programme, Nigeria, 148 pp

Cock JH (1985) Cassava. New potential for a neglected crop. Westview Press, Boulder and London, 191pp

Cock JH, Franklin D, Sandoval G, Juri P (1979) The ideal cassava plant for maximum yield. Crop Sci 19:271–279

Dixon AGO, Asiedu R, Bokanga M (1994) Breeding of cassava for low cyanogenic potential problems, progress and prospects. ActaHorticulturae 375:153–161

EFDI-Technoserve (2005) Assessment of different models of cassava processing enterprises for the south and South-East of Nigeria, including the Niger Delta. Draft Final Report submitted to IITA-CEDP, March 2005

Ekanayake IJ (1998) Screening for abiotic stress resistance in root and tuber crops. IITA Res Guide 68:46

Ekanayake IJ, Githunguri CM (2000) Implications of biophysical site characteristics on growth and sustainable cassava production in the savannas of Nigeria. Niger Meteorol Soc J 2(2):33–45

Ekanayake IJ, Osiru DSO, Porto MCM (1997a) Morphology of cassava. IITA Res Guide 61:1–30

Ekanayake IJ, Osiru DSO, Porto MCM (1997b) Agronomy of cassava. IITA Res Guide 60:1–20

Ezedinma C, Patino M, Sanni L, Okechukwu R, Ilona P, Akoroda M, Dixon A (2005) Investment options in the High Quality Cassava Flour (HQCF) enterprise. Presented at the Stakeholders meeting on Strategies on sourcing high quality cassava flour. IITA, Ibadan

FAO (1990) Roots, tubers, plantains and bananas in human nutrition. FAO, Rome

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO (2017) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2017. Building resilience for peace and food security. FAO, Rome. 232pp. ISBN 978-92-5-109888-2

Githunguri CM (1983a) Pests of cassava. In: Proceedings: Cassava production workshop, 7th–8th February 1983, Malindi, Kenya. 6p

Githunguri CM (1983b) The place of cassava in coast agriculture and relevance to the research programme. In: Proceedings: Cassava production workshop, 7th–8th February 1983, Malindi, Kenya. 24p

Githunguri CM (1995) Cassava food processing and utilization in Kenya. In: Egbe TA, Brauman A, Griffon D, Treche S (eds) Cassava food processing. CTA, ORSTOM, Wageningen, pp 119–132

Githunguri CM (2002) The influence of agro-ecological zones on growth, yield and accumulation of cyanogenic compounds in cassava. A thesis submitted in full fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Crop Physiology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Nairobi, 195pp

Githunguri CM, Amata R (2015) Drought mitigating technologies: an overview of Cassava and Sweetpotato Production in Mukuyuni Division Makueni District in Semi-Arid Eastern Kenya. In the book “Adapting African Agriculture to Climate Change. Transforming Rural Livelihoods. The contribution of land and water management to enhanced food security and climate change adaptation and mitigation in the African continent” Edited by Walter Leal Filho, Anthony O. Esilaba, K. P. C. Rao and G. Sridhar” ISSN 1610–2010 ISSN 1610–2002 (electronic) Climate Change Management. ISBN 978–3–319-12999-0 ISBN 978–3–319-13000-2 (eBook). DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13000-2. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955614. Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London. © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015. pp 225–235

Githunguri CM, Njaimwe AN (2013a) Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) identification and management. KARI Information brochure series 2013/86. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)

Githunguri CM, Njaimwe AN (2013b) Cassava leaf spots disease identification and management. KARI Information brochure series 2013/88. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)

Githunguri CM, Njaimwe AN (2013c) Cassava anthracnose disease identification and management. KARI Information brochure series 2013/93. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)

Githunguri CM, Njaimwe AN (2013d) Cassava mosaic disease identification and management. KARI Information brochure series 2013/94. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO)

Githunguri CM, Mailu AM, Kariuki CW, Gatumbi RW (1992) An overview of cassava diseases and pests in Kenya. In: Root and tuber pest management in Kenya. Proceedings of a national workshop, 3rd–7th August 1992 Mombasa, Kenya, pp 42–48

Githunguri CM, Ekanayake IJ, Chweya JA, Dixon AGO, Imungi J (1998) The effect of different agro-ecological zones on the cyanogenic potential of six selected cassava clones. Post-harvest technology and commodity marketing. IITA, Ibadan, pp 71–76

Githunguri CM, Migwa YN, Ragwa SM, Karoki MM (2003) Cassava and sweetpotato agronomy, physiology, breeding, plant protection and product development. Root and Tuber Crops Programme in KALRO-Katumani. Paper presented at the Joint Planning meeting organized under the Eastern Province Horticulture and Traditional Food Crops Project, held at Machakos, Kenya on 5th- 7th March 2003, 5p

Githunguri CM, Karuri EG, Kinama JM, Omolo OS, Mburu JN, Ngunjiri PW, Ragwa SM, Kimani SK, Mkabili DM (2006) Sustainable productivity of the Cassava value chain: an emphasis on challenges and opportunities in processing and marketing Cassava in Kenya and beyond. A project proposal present to the Kenya Agricultural Productivity Project (KAPP) Competitive Agricultural Research Grant Fund, Research Call Ref No.KAPP05/PRC- CLFFPS –03. KAPP Secretariat 106p

Githunguri CM, Mwiti S, Migwa Y (2007a) Cyanogenic potentials of early bulking cassava planted at Katumani, a semi-arid area of Eastern Kenya. Part 2 of 4 ISSN 1023-070/2007 African Crop Science Society, Uganda, Vol. 8, pp 925 – 927

Githunguri CM, Karuri EG, Kinama JM, Omolo OS, Mburu JN, Ngunjiri PW, Ragwa SM, Mkabili DM (2007b) Sustainable productivity of the Cassava value chain: an emphasis on challenges and opportunities in processing and marketing Cassava in Kenya and beyond. In: Githunguri CM, Kwena K, Mungube E, Gatheru M (eds). KARI Katumani research centre annual report 2006. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO). pp. 149

Githunguri CM, Amata R, Lung’ahi EG, Musili R (2014) Cassava: a promising food security crop in Mutomo, a semi-arid food deficit district in Kitui County of Kenya. Int J Agric Resour Gov Ecol 10(3):311–323

Githunguri CM, Lung’ahi EG, Kabugu J, Musili R (2015) Cassava farming transforming livelihoods among smallholder farmers in Mutomo a Semi-Arid District in Kenya. In the book “Adapting African Agriculture to Climate Change. Transforming Rural Livelihoods. The contribution of land and water management to enhanced food security and climate change adaptation and mitigation in the African continent” Edited by Walter Leal Filho, Anthony O. Esilaba, K. P. C. Rao and G. Sridhar” ISSN 1610–2010 ISSN 1610–2002 (electronic) Climate Change Management. ISBN 978–3–319-12999-0 ISBN 978–3–319-13000-2 (eBook). DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13000-2. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014955614. Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London. © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015. pp 215–224

Githunguri CM, Lung’ahi EG, Amata R, Gatheru M, Musili R, Njiru E (2016) The effect of a dry agroecological zone on selected growth and yield parameters of three elite cassava genotypes grown in Mutomo Sub-County of Kitui County in Kenya. In: Esilaba A, Githunguri C, Kimani S, Njeru P, Lekasi J, Maina F, Muniafu M, Miriti J, Gachene C, Baaru M, Muriuki A, Nyamwaro S, Kibunja C, Mangale N (eds) Proceedings of the 27th soil science society of East Africa and the 6th African soil science society conference, held 20–25 October 2013. Soil Science Society of East Africa (SSSEA), Nakuru, pp 1100–1104

Githunguri CM, Gatheru M, Ragwa SM (2017a) Cassava production and utilization in the coastal, eastern and western regions of Kenya. In: Klein C (ed) Chapter 3 handbook on cassava: production, potential uses and recent advances. Series: plant science research and practices. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge. ISBN: 978-1-53610-291-8

Githunguri CM, Gatheru M, Ragwa SM (2017b) Status of cassava processing and challenges in the coastal, eastern and western regions of Kenya. In: Klein C (ed) Chapter 11 handbook on cassava: production, potential uses and recent advances. Series: plant science research and practices. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge. ISBN: 978-1-53610-291-8

Githunguri CM, Gatheru M, Ragwa SM (2017c) Trend in the trade of cassava products in the coastal, eastern and western regions of Kenya. In: Klein C (ed) Chapter 19 handbook on cassava: production, potential uses and recent advances. Series: plant science research and practices. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., Hauppauge. ISBN: 978-1-53610-291-8

IITA (1990a) Cassava in tropical Africa. Reference Manual IITA, Ibadan, Nigeria, 176pp

IITA (1990b) Targeting cassava breeding and selection. In: Proceedings of the 4th West and Central Africa Root Crops workshop. Lome, Togo. 12–16 December 1988. IITA Meeting Reports Series 1988/6, pp 27–30

Jarvis A, Ramirez-Villegas J, Vanessa B, Campo H, Navarro-Racines C (2012) Is cassava the answer to African climate change adaptation? Trop Plant Biol 5(1):9–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12042-012-9096-7

KALRO (1995) Cassava research priorities at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, Cassava Priority Setting Working Group. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO).

Lusweti CM, Kiiya W, Kute C, Laboso A, Nkonge C, Wanjekeche E, Lobeta T, Layat S, Kakuko A, Chelang E (1997) The farming systems of Sebit: In: Summary from PRA activities. Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), Kitale, pp 54–67

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) (2005) Strategy for revitalizing agriculture 2004–2014. Ministry of Agriculture, Nairobi, Kenya, 23pp

Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (2018) Climate risk profile for Lamu County. Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series. The Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (MoALF), Nairobi, Kenya. 24pp. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/9629

Monger W, Tomlinson J, Booonham N, Nielsen SL (2010) Development and inter-laboratory evaluation of real-time PCR assays for the detection of pospiviroids. J Virol Methods 169(1):207–210

Nartey F (1981) Cyanogenesis in tropical feeds and foodstuffs. In: Vennesland B (ed) Cyanide in biology. Academic Press, New York, 250pp

Naskar SK, Singh DP, Srinivasan G (1989) Performance of cassava varieties in the laterite soils of Bhubaneswar and their yield stability. J Root Crops 15(1):29–31

National Economic and Social Council of Kenya (NESC) (2007) Kenya vision 2030. Office of the President, Nairobi

Nweke FI, Dixon AGO, Asadu CLA, Folayan SA (1994) Cassava variety needs of farmers and the potential for production growth in Africa. COSCA. Collaborative study of Cassava in Africa, COSCA Working Paper No. 10

Nweke FI, Spencer DSC, Lynam JK (2002) Cassava transformation. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria, 273p

Odendo M, DW Kilambya, PJ Ndolo (2001) Sweetpotato research priorities at the Kenya Agricultural Research Institute. Paper Presented at the Stakeholders Workshop for Sweetpotato Priority Setting, held at Machakos, Kenya, 27–28th September 2001, 19pp

Odongo GO (2008) Analysis of level of toxicity (cyanogenic potential) of various cassava varieties and cassava based products. A Trade Project Report in the Kenya Polytechnic University College Department of Applied Science submitted to the Kenya National Examination Council in partial fulfilment of the requirements for award of Diploma in Food Technology, 35pp

Onwueme IC (1978) The tropical tuber crops. Yams, cassava, Sweetpotato, Cocoyams. Wiley, Chichester, 234p

Onyango C, Ngunjiri PW, Oguta TJ, Wambugu SM (2006) Small-scale processing technologies for selected traditional and horticultural food crops in Kenya. Kenya Industrial Research and Development Institute, Nairobi, Kenya, 166pp

Rai M, Dhandar DG, Varma SP (1986) Variability studies of cassava varieties on growth and yield under tropical conditions. J Root Crops 12(1):25–28

Tivana LD, Bvochora J (2005) Reduction of cyanogenic potential by heap fermentation of cassava roots. Cassava Cyanide Diseases Network News, Issue No. 6 2005, 1p

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry

Githunguri, C.M., Njiru, E.N. (2021). Role of Cassava and Sweetpotato in Mitigating Drought in Semi-Arid Makueni County in Kenya. In: Leal Filho, W., Oguge, N., Ayal, D., Adeleke, L., da Silva, I. (eds) African Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_11-1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42091-8_11-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-42091-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-42091-8

eBook Packages: Springer Reference Earth and Environm. ScienceReference Module Physical and Materials ScienceReference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences