Abstract

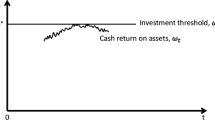

This chapter describes a business model in a contingent claim modeling framework. The model defines a “primitive firm” as the underlying risky asset of a firm. The firm’s revenue is generated from a fixed capital asset and the firm incurs both fixed operating costs and variable costs. In this context, the shareholders hold a retention option (paying the fixed operating costs) on the core capital asset with a series of growth options on capital investments. In this framework of two interacting options, we derive the firm value.

The chapter then provides three applications of the business model. Firstly, the chapter determines the optimal capital budgeting decision in the presence of fixed operating costs and shows how the fixed operating cost should be accounted by in an NPV calculation. Secondly, the chapter determines the values of equity value, the growth option, and the retention option as the building blocks of primitive firm value. Using a sample of firms, the chapter illustrates a method in comparing the equity values of firms in the same business sector. Thirdly, the chapter relates the change in revenue to the change in equity value, showing how the combined operating leverage and financial leverage may affect the firm valuation and risks.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

We use an optimization subroutine, GlobalSearch, written in Mathematica. The description of the procedure is provided at www.loehleenterprises.com.

- 2.

For clarity of the exposition, let the NPV be defined by Eq. 75.13. To be precise, the expected cash flow may not be perpetual in the presence of default. We will explain the implication of default on the free cash flow later in this section.

References

Botteron, P., Chesney, M., & Gibson-Anser, R. (2003). Analyzing firms strategic investment decisions in a real options framework. International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 13, 451–479.

Brennan, M. J., & Schwartz, E. S. (1985). Evaluating natural resource investments. Journal of Business, 58, 135–157.

Cortazar, G., Schwartz, E. S., & Casassus, J. (2001). Optimal exploration investments under price and geological-technical uncertainty: A real options model. R&D Management, 31, 181–190.

Demsetz, H. (1968). The cost of transacting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 82, 33–53.

Fontes, D. B. M. M. (2008). Fixed versus flexible production systems: A real option analysis. European Journal of Operational Research, 188, 169–184.

Gilroy, B. M., & Lukas, E. (2006). The choice between greenfield investment and cross-border acquisition: A real option approach. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 46, 447–465.

Ho, T. S. Y., & Lee, S. B. (2004a). The Oxford guide to financial modeling. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ho, T. S. Y., & Lee, S. B. (2004b). Valuing high yield bonds: A business modeling approach. Journal of Investment Management, 2, 1–12.

Ho, T. S. Y., & Marcis, R. (1984). Dealer bid-ask quotes and transaction prices: An empirical study of some AMAX options. Journal of Finance, 39, 23–45.

McDonald, R. L. (2006). The role of real options in capital budgeting: Theory and practice. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 18, 28–39.

Merton, R. (1973). On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. Journal of Finance, 29, 449–470.

Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 147–175.

Myers, S. C. (1984). Finance theory and financial strategy. Interface, 14, 126–137, reprinted in 1987, Midland Corporate Finance Journal 5, 6–13.

Sodal, S., Koekebakker, S., & Aadland, R. (2008). Market switching in shipping: A real option model applied to the valuation of combination carriers. Review of Financial Economics, 17, 183–203.

Stoll, H. R. (1976). Dealer inventory behavior: An empirical investigation of NASDAQ stocks. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 11, 356–380.

Triantis, A., & Borison, A. (2001). Real options: State of the practice. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14, 8–24.

Trigeorgis, L. (1993). The nature of option interactions and the valuation of investments with multiple real options. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 28, 1–20.

Villani, G. (2008). An R&D investment game under uncertainty in real option analysis. Computational Economics, 32, 199–219.

Wirl, F. (2008). Optimal maintenance and scrapping versus the value of back ups. Computational Management Science, 5, 379–392.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1: Derivation of the Risk-Neutral Probability

The risk-neutral probabilities p(n,i) can be calculated from the binomial tree of V p . Let V p (n,i) be the firm value at node (n,i). In the upstate, the firm value is

By the definition of the binomial process of the gross return on investment,

Further, the firm pays a cash dividend of C u = V p (n,i) × ρ × e σ. Therefore, the total value of the firm V u p , an instant before the dividend payment in the upstate, is

Similarly, the total value of the firm V d p , an instant before the dividend payment in the downstate, is

Then the risk-neutral probability p is defined as the probability that ensures the expected total return is the risk-free return.

Substituting V p , V u p , V d p into equation above and solve for p, we have

Where \( A=\frac{1+{R}_F}{1+\rho } \).

Appendix 2: The Model for the Fixed Operating Cost at Time T

When the firm may default the fixed operating cost, the fixed operating cost can be viewed as a perpetual debt of a risk bond. The valuation formula of the perpetual debt is given by Merton (1973).

Where

-

V = the primitive firm value

-

FC = fixed cost per year

-

r f = risk free rate

-

Γ = the gamma function (defined in the footnote)

-

σ = the standard deviation of \( \tilde{ GRI} \)

-

M (•) = the confluent hypergeometric function (defined in the footnote)

where

Appendix 3: The Valuation Model Using the Recombining Lattice

In this model specification, we assume that the GRI stochastic process follows a recombining binomial lattice:

where n = 0, 1,… T and j = 0, …, n.

At time T, the horizon date, consider the node (T, j); j is the state on a recombining lattice. Suppose that the firm has made k investments in the period T, where 0 ≤ k ≤ T − 1. The firm value is given by Eq. 75.32:

and CA is the initial capital asset.

Now we roll back one period. We then compare the firm value with or without making an investment I. Given that the firm at the end of the period T − 1 has already invested k times and would not invest at time T − 1, the firm value is

If the firm at that time invests in the capital asset, then the firm value is

Optimal decision is to maximize the values of the firm under three possible scenarios: taking the investment, not taking the investment, or defaulting. Therefore, the value of the firm at the node (T − 1, j) with k investments is

Now we can determine the firm value recursively for each n, n = T − 1, T − 2,…1.

At the initial period,

The firm value at the initial time can then be derived by recursively rolling back the firm value to the initial point, where n = 0. We follow the method of the fiber bundle modeling approach in Ho and Lee (2004a).

To illustrate, we use a simple numerical example. Following the previous numerical example, we assume that the GRI is 0.1, the capital asset CA is 30, the risk-free rate and the cost of capital are both 10 %, the risk-neutral probability is 0.425557, the volatility 30 %, the fixed cost FC is 3, and finally the investment is 1.

Given the above assumption, the binomial process is presented below.

The binomial lattice of GRI

Time | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

j | GRI | |||

3 | 0.245960311 | |||

2 | 0.18221188 | 0.134985881 | ||

1 | 0.134985881 | 0.1 | 0.074081822 | |

0 | 0.1 | 0.074081822 | 0.054881164 | 0.040656966 |

Given the GRI binomial lattice, we can now derive the firm value lattices. The values are derived by backward substitution. The firm value depends on the capital asset level CA, the state j, and the time n.

Firm value | V(n,j,CA) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

State j | CA | ||||

3 | 55.2836 | 32 | |||

2 | 14.9999 | 32 | |||

1 | 0.0000 | 32 | |||

0 | 0.0000 | 32 | |||

j | |||||

3 | 52.5780 | 31 | |||

2 | 31.0516 | 13.5150 | 31 | ||

1 | 5.3286 | 0.0000 | 31 | ||

0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 31 | ||

j | |||||

3 | 49.8725 | 30 | |||

2 | 29.0473 | 12.0302 | 30 | ||

1 | 14.9802 | 4.6541 | 0.0000 | 30 | |

0 | 6.329610 | 1.0230 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 30 |

Time n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

At time 3, the firm values are derived by Eq. 75.32 for each level of outstanding capital asset level at time 3, an instant before the investment decision. Then the firm values for time 2 are derived by Eq. 75.34. Once again, the firm value depends on the outstanding CA level. The firm value at time 0 does not involve any investment decision, and therefore, it is derived by rolling back from the firm values where the CA level is 30.

Appendix 4: Input Data of the Model

The input data of the model are derived from the balance sheets and income statements of the firms.

IS | Target | Lowe’s | Wal-Mart | Darden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Revenue | 39,888 | 22,111.1 | 217,799 | 4,021.2 |

Costs of sales | 27,246 | 15,744.2 | 168,272 | 3,127.7 |

Gross profit | 12,642 | 6,366.9 | 49,527 | 893.5 |

Gross profit margin (m)a | 0.3169 | 0.2880 | 0.2274 | 0.2222 |

Fixed cost | 8,883 | 4,053.2 | 36,173 | 407.7 |

Depreciation | 1,079 | 534.1 | 3,290 | 153.9 |

Interest cost | 464 | 180 | 1,326 | 31.5 |

Other incomes | 0 | 24.7 | 2,013 | 0.9 |

Pretax incomes | 2,216 | 1,624.3 | 10,751 | 301.3 |

Tax | 842 | 601 | 3,897 | 104.2 |

Effective tax ratio (τ)b | 0.3800 | 0.3700 | 0.3625 | 0.3458 |

Balance sheet | Target | Lowe’s | Wal-Mart | Darden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Capital assets | 13,533 | 8,653.4 | 45,750 | 1,779.5 |

Gross return on invest (GRI)a | 2.9475 | 2.5552 | 4.7606 | 2.2597 |

LTDb | 8,088 | 3,734 | 18,732 | 517.9 |

Book equity | 7,860 | 6,674.4 | 35,102 | 1,035.2 |

Market information | Target | Lowe’s | Wal-Mart | Darden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sharesa | 902.8 | 775.7 | 4,500 | 176 |

Stock pricea | 44.41 | 46.07 | 59.98 | 18.6 |

Market capitalization (equity)a | 40,093 | 35,736 | 269,910 | 3,274 |

Risk free rate (Rf)b | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

Coupon rateb | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

Max investc | 2,115 | 2,060.5 | 7,000 | 201 |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry

Ho, T.S.Y., Lee, S.B. (2015). Business Models: Applications to Capital Budgeting, Equity Value, and Return Attribution. In: Lee, CF., Lee, J. (eds) Handbook of Financial Econometrics and Statistics. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7750-1_75

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7750-1_75

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-7749-5

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-7750-1

eBook Packages: Business and Economics