Abstract

Background

The aim of this paper was to explore disparities associated with the route of hysterectomy in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) health system and to evaluate whether the hysterectomy clinical pathway implementation impacted disparities in the utilization of minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH).

Methods

We performed a retrospective medical record review of all the patients who have undergone hysterectomy for benign indications at UPMC-affiliated hospitals between fiscal years (FY) 2012 and 2014.

Results

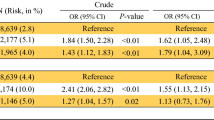

A total number of 6373 hysterectomy patient cases were included in this study: 88.7% (5653) were European American (EA), 11.02% (702) were African American (AA), and the remaining 0.28% (18) were of other ethnicities. We found that non-EA, women aged 45–60, traditional Medicaid, and traditional Medicare enrollees were more likely to have a total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). Residence in higher median income zip code (> $61,000) was associated with 60% lower odds of undergoing TAH. Both FY 2013 and 2014 were associated with significantly lower odds of TAH. Logistic regression results from the model for non-EA patients for FY 2012 and FY 2014 demonstrated that FY and zip code income group were not significant predictors of surgery type in this subgroup. Pathway implementation did not reduce racial disparity in MIH utilization.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that there is a significant disparity in MIH utilization, where non-EA and Medicaid/Medicare recipients had higher odds of undergoing TAH. Further research is needed to investigate how care standardization may alleviate healthcare disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Nelson AR, Smedley BD. Stith AY. Unequal treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2002.

Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21:60–76.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Your guide to choosing quality health care: a quick look at quality. 2016. http://archive.ahrq.gov/consumer/qnt/. Accessed May 1 2017.

Carter-Pokras O, Baquet C. What is a “health disparity”? Public Health Rep. 2002;117:426.

Nelson AR, Smedley BD, Stith AY, Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version). National Academies Press; 2002.

Ahmed AT, Welch BT, Brinjikji W, Farah WH, Henrichsen TL, Murad MH, et al. Racial disparities in screening mammography in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:157–65. e9

Doshi RP, Aseltine RH Jr, Sabina AB, Graham GN. Racial and ethnic disparities in preventable hospitalizations for chronic disease: prevalence and risk factors. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;

Musselwhite LW, Oliveira CM, Kwaramba T, de Paula PN, Smith JS, Fregnani JH, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytol. 2016;60:518–26.

Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, Velopulos C, Bentley JM, Cornwell EE 3rd, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:482–92. e12

Schneider EC, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Racial disparity in influenza vaccination: does managed care narrow the gap between african americans and whites? JAMA. 2001;286:1455–60.

Epstein AM, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Gatsonis C, Leape LL, Piana RN. Race and gender disparities in rates of cardiac revascularization: do they reflect appropriate use of procedures or problems in quality of care? Med Care. 2003;41:1240–55.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–43.

Healy AJ, Malone FD, Sullivan LM, Porter TF, Luthy DA, Comstock CH, et al. Early access to prenatal care: implications for racial disparity in perinatal mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:625–31.

Lee J, Jennings K, Borahay MA, Rodriguez AM, Kilic GS, Snyder RR, et al. Trends in the national distribution of laparoscopic hysterectomies from 2003 to 2010. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:656–61.

Jacoby VL, Fujimoto VY, Giudice LC, Kuppermann M, Washington AE. Racial and ethnic disparities in benign gynecologic conditions and associated surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:514–21.

Chan JK, Gardner AB, Taylor K, Blansit K, Thompson CA, Brooks R, et al. The centralization of robotic surgery in high-volume centers for endometrial cancer patients—a study of 6560 cases in the US. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:128–32.

Mayo Clinic. Uterine fibroids. 2017. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/uterine-fibroids/symptoms-causes/dxc-20212514. Accessed July 6 2017.

Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R, Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG. 2017; doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14640.

Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160–6.

Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L, Hughes RG, Regan J, Gaston MH. Inequality in America: the contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58:234–48.

Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, Stolley PD, Guzinski GM. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1996;41:483–90.

Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, Myers ER. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:881–4.

Linkov F, Sanei-Moghaddam A, Edwards RP, Lounder PJ, Ismail N, Goughnour SL, et al. Implementation of hysterectomy pathway: impact on complications. Womens Health Issues. 2017; doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.02.004.

ACOG. Chosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. 2017. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Choosing-the-Route-of-Hysterectomy-for-Benign-Disease. Accessed July 10 2017.

Sanei-Moghaddam A, Ma T, Goughnour SL, Edwards RP, Lounder PJ, Ismail N, et al. Changes in hysterectomy trends after the implementation of a clinical pathway. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:139–47.

Mansuria SM, Comerci J, Edwards R, Sanei Moghaddam A, Ma T, Linkov F. Changes in hysterectomy trends and patient outcomes following the implementation of a clinical pathway [7]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(Suppl 1):3s.

Venkitaraman AR. Cancer suppression by the chromosome custodians, BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2014;343:1470–5.

Jacoby VL, Autry A, Jacobson G, Domush R, Nakagawa S, Jacoby A. Nationwide use of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal and vaginal approaches. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1041–8.

Abenhaim HA, Azziz R, Hu J, Bartolucci A, Tulandi T. Socioeconomic and racial predictors of undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy for selected benign diseases: analysis of 341487 hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:11–5.

Spencer CS, Gaskin DJ, Roberts ET. The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff. 2013;32:1731–9.

Hasan O, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:452–9.

Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:668–77.

Marsh EE, Ekpo GE, Cardozo ER, Brocks M, Dune T, Cohen LS. Racial differences in fibroid prevalence and ultrasound findings in asymptomatic young women (18–30 years old): a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1951–7.

Betancourt J, Green A, King R, Tan-McGrory A, Cervantes M, Renfrew M. Improving quality and achieving equity: a guide for hospital leaders. Boston: Disparities Solutions Center and Institute for Health Policy, Massachusetts General Hospital; 2008.

UPMC. By the numbers: UPMC facts and figures. 2015. http://www.upmc.com/ABOUT/FACTS/NUMBERS/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed May 1 2017.

Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–90.

Gordon HS, Street RL, Sharf BF, Kelly PA, Souchek J. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients' perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:904–9.

Collins KS,Fund C, Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. Commonwealth Fund New York; 2002.

U.S. Census Bureau. nnFacts. 2015. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00. Accessed May 1 2017.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the “Bench at the Bedside” program of the Beckwith Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Suketu Mansuria declares speakers bureau surgeon educator with Covidien/Medtronic. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required for this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanei-Moghaddam, A., Kang, C., Edwards, R.P. et al. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Hysterectomy Route for Benign Conditions. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 758–765 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0420-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0420-7