Abstract

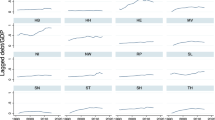

In this paper, we evaluate fiscal sustainability of five regional groups in the EU using the dataset of 26 countries for the period 1950–2014. To this end, we estimate their policy rules in which primary surpluses respond to public debt and examine whether estimated policy rules satisfy the conditions for fiscal solvency. In the baseline solvency tests with time-invariant marginal responses of primary surpluses, we find that estimated policy rules satisfy the solvency condition that the marginal response be positive for the Benelux, northern, and eastern groups but fail to do so for the western and southern groups. When estimating their policy rules separately for eurozone and non-eurozone countries, we find that long-term fiscal sustainability of eurozone countries is more questionable in the sense that non-eurozone countries in all regional groups have significantly positive marginal responses, whereas eurozone countries in most regional groups do not. Finally, more general solvency tests that allow time-varying marginal responses reveal that only the Southern group fails to satisfy the generalized solvency conditions that marginal responses be always nonnegative and positive infinitely often. These findings seem to be consistent with the fact that countries in the Southern group experienced severe fiscal crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The average public debt–GDP ratio is taken over the 26 EU countries in our sample though there are 28 member countries in the EU as of May 2016. We exclude Malta from our analysis because of limited data availability, and Croatia because it joined the EU late in our sample period in 2013.

Obviously, the division of the sample period is irrelevant to non-eurozone countries.

All equations used in this section are derived in detail in Section A of the online appendix.

In standard DSGE models, \( q_{t,t + n} = \beta^{n} u^{{\prime }} (c_{t + n} )/u^{{\prime }} (c_{t} ) \) with the standard notation, but it can be defined generally for various dynamic models.

As of July 2015, the EU has 28 member countries. Malta is excluded from the sample due to the lack of data availability. Croatia is also excluded as it joined the EU in 2013.

For more details on the construction of our dataset and its sources, refer to Section B of the online appendix.

Notice that Lithuania is classified as a non-eurozone country because it joined the eurozone after the sample period.

The division of the two subperiods may not coincide with the division between the pre-eurozone and eurozone subperiods for countries that joined the eurozone after 1999. We divide the sample period in this way in Table 2 for illustration.

Our methodology follows Mendoza and Ostry (2008), who estimated the marginal response of primary surpluses to public debt for two groups, industrial countries and emerging economies, with a sample of 56 countries. They tested the assumption of group-specific marginal responses and found that 75% of the countries have the same ρ. They interpret this finding as lending support to their specification.

To verify this argument, we estimate the following country-specific regression: \( s_{t} = \rho d_{t} + \alpha_{g} {\text{GVAR}}_{t} + \alpha_{y} {\text{YVAR}}_{t} + \varepsilon_{t} \) for Ireland and for the period up to 2007. We find that the estimate of ρ is 0.048 and the corresponding p value is 0.020.

The regression coefficients specific to the eurozone subperiod can be biased because the eurozone subperiod is relatively short and includes the Great Recession. However, we think the short-sample bias is likely to be small because we collect information from the panel of multiple countries to estimate the regression coefficients. Also, time dummies can deal with the influence of the Great Recession at least partly.

Notice that no coefficient exists for the Benelux, western, and southern groups in column [2] because all countries in these groups belong to the eurozone.

As emphasized by CCD, the condition (C2) can hold for any frequency of positive marginal responses. For example, even if the marginal response is positive once in every 100 years, (C2) would still be satisfied.

The nonlinear response model is nonlinear in the sense that it includes a nonlinear explanatory variable, not in the sense that regression coefficients are nonlinear.

In our online appendix, we also present the results of other types of panel unit-root tests such as the Im–Pesaran–Shin (2003) tests and the panel Phillips–Perron (PP) tests (Choi 2001). We only report the results of the panel ADF tests because the three types of panel unit-root tests yield similar results. The appendix also includes details on the methodology of the panel unit-root tests.

Trehan and Walsh (1991) provided multiple solvency criteria to test fiscal solvency. Here, we examine just one of their solvency criteria, which is drawn from Proposition 2 of their paper.

As noted, there can be additional technical assumptions for some solvency tests. We do not specify them here for simplicity. For those assumptions and other details on the solvency tests, refer to the papers cited here.

References

Ahmed, S., & Rogers, J. H. (1995). Government budget deficits and trade deficits: Are present value constraints satisfied in long-run data? Journal of Monetary Economics, 36, 351–374.

Barro, R. J. (1986). U.S. deficits since world war I. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 88(1), 195–222.

Bohn, H. (1995). The sustainability of budget deficits in a stochastic economy. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 27(1), 257–271.

Bohn, H. (1998). The behavior of U.S. public debt and deficits. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3), 949–963.

Bohn, H. (2002). Government asset and liability management in an era of vanishing public debt. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 34(3), 887–933.

Bohn, H. (2005). The sustainability of fiscal policy in the United States. CESifo working paper, no. 1446.

Canzoneri, M. B., Cumby, R. E., & Diba, B. T. (2001). Is the price level determined by the needs of fiscal solvency? American Economic Review, 91(5), 1221–1238.

Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20, 249–272.

Hakkio, C. S., & Rush, M. (1991). Is the budget deficit too large? Economic Inquiry, 29, 429–445.

Hamilton, J. D., & Flavin, M. (1986). On the limitations of government borrowing: A framework for empirical testing. American Economic Review, 76, 808–819.

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74.

Mauro, P., Romeu, R., Binder, A., & Zaman, A. (2015). A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 76, 55–70.

Mendoza, E. G., & Ostry, J. D. (2008). International evidence on fiscal solvency: Is fiscal policy “responsible”? Journal of Monetary Economics, 55, 1081–1093.

Trehan, B., & Walsh, C. E. (1988). Common trends, the government budget constraint and revenue smoothing. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12, 425–444.

Trehan, B., & Walsh, C. E. (1991). Testing intertemporal budget constraints: Theory and applications to U.S. federal budget and current account deficits. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 13, 210–223.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank the editor and two anonymous referees of this journal for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Kw., Kim, JH. & Sung, T. A test of fiscal sustainability in the EU countries. Int Tax Public Finance 25, 1170–1196 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9488-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-018-9488-1